A few years ago, I built a special tour for a group of Diaspora Jews who were in Israel for a program that combined studying with volunteering for human rights organizations active in the West Bank. Entitled ‘Power and Powerlessness in the Old City,’ it was built around the observation that Jewish power in Jerusalem, the manifestations of which are today impossible to ignore, is a relatively recent phenomenon. For most of the past 2,000 years prior to 1967, though, Jews were completely powerless in the city, and this context is essential in understanding the current reality.

Nowhere is this more pertinent than at the Western Wall. For hundreds of years, Jews prayed in a narrow alley between the wall and the houses of the Maghrabi Quarter, which had been settled by North African Muslims at the behest of Saladin following his conquest of the city from the Crusaders in 1187. In 1967, following victory in the Six-Day War, Israel quickly demolished the neighbourhood to make way for the Western Wall Plaza where visitors now gather.

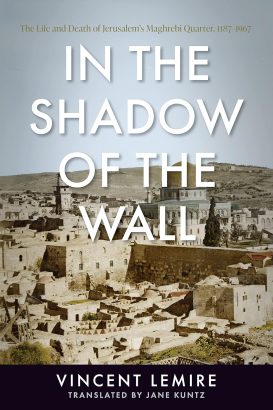

This destruction is often cited as one of Israel’s most nefarious deeds, particularly as few traces of the Maghrabi Quarter remain today. And now it is at the heart of a new book by the French historian Vincent Lemire, In the Shadow of the Wall: The Life and Death of Jerusalem’s Maghrebi Quarter, 1187-1967.

Lemire himself concedes that ‘the history of the Maghrebi Quarter is situated not only “in the shadow of the Wall” but also in the shadow of the Temple, which makes this history all the more thorny and challenging.’ He doesn’t, though, explain why this is. After the destruction of the Temple, Jerusalem was ruled by successive empires: the Romans, the Byzantines, the Persians (briefly), several early Islamic dynasties, the Crusaders, the Ayyubids, the Mamluks, the Ottomans, and the British. With some rare and minor exceptions, none of these rulers allowed Jews to pray on the Temple Mount, let alone rebuild the temple (an exception to this may have been Julian the Apostate in the fourth century). Instead, Jews sought to pray as close as they could to where the Temple had previously stood. At times this was the Mount of Olives, at other times Mount Zion, but for most of the last 500 years, and possibly earlier, it was the Western Wall, a retaining wall built during the reign of King Herod to support the massive plaza upon which was placed the expanded temple complex.

It’s also important to note that the Western Wall is not, as Lemire writes, ‘the central holy place of Judaism.’ Benjamin Netanyahu made the same mistake a few years back, although at least he had the excuse of diplomatic niceties. As the Talmud makes clear in Berachot 30A, the Temple Mount has always been the holiest place in Judaism. What changed is that Jews were now prevented from praying there, and in response the rabbis enacted their own prohibition on going up to the site, for fear of desecrating it (the issue is that one shouldn’t wander in parts that only the priests were permitted to visit). As a result, by the fourth century, Rabbi Aha said in Midrash Tanhuma (Book of Exodus 10) ‘The divine presence never passes from the Western Wall,’ although there is some debate as to exactly which wall he was referring to.

Benjamin of Tudela, writing during the Crusader period, refers to the Western Wall (‘In front of this place is the Western Wall, which is one of the walls of the Holy of Holies. This is called the Gate of Mercy, and thither come all the Jews to pray before the wall at the court of the Temple’), but it’s also not entirely clear which Western Wall he’s referring to, and it’s only by the sixteenth century that we can be sure Jews were praying permanently at the site, even if the precise dating and origins of how this came to be is still uncertain. According to one theory, they began praying there followed an earthquake that caused major damage in 1546. The rubble was cleared, creating an open, accessible area where Jews could pray. The narrow alley separating the Maghrabi Quarter from the wall then became a permanent place of Jewish prayer. Later, according to an 18th century tradition, Suleiman the Magnificent ordered the consecration of a prayer plaza for the Jews at the site. In exchange, Jews were required to pay a tax to the Ottoman rulers and transfer funds to the Maghrabi Quarter.

According to testimony, in the nineteenth century, Muslim residents of the Maghrabi quarter passed through the plaza with their pack animals, who discharged their excretions there, and they also threw refuse into the plaza. This led to Jewish attempts to purchase the Western Wall and its surroundings, for example Moses Montefiore when he first visited Palestine in 1827/28. In 1840 the Waqf sent a letter to the Governor of Jerusalem: ‘We legally attest that it is impermissible to provide them assistance to pave this place. The Jews must be warned not to raise their voices when praying or speaking. They need to be given authorization to come venerate this place in accordance with their ancient custom.’

Due to increased Jewish presence at the site, the plaza was paved in the mid-1850s. In 1866, Montefiore sought to build a roof above the plaza to protect from the heat and the rain – the Muslim governor initially permitted this but later reversed his decision. Then, in 1887, Baron Edmond de Rothschild made another failed attempt to purchase the site. Later, during the British Mandate period, fears of a Jewish takeover led to an intensification of the tradition that the Western Wall was the al-Buraq wall, the place where Muhammad had tethered the magical steed on which he had travelled from Mecca before ascending to heaven. A resolution of the Municipal Council of the Jerusalem district in November 1911, where Arabs formed the majority, ruled that Jews had no rights to the Western Wall and were prohibited from bringing religious objects to the plaza.

With this background out of the way, we can now turn to the focus of the book, the history of the Maghrebi Quarter:

Even if it is obvious that the fate of the Maghrebi Quarter was increasingly bound up with that of the Western Wall starting in the early twentieth century, when the sanctuary was becoming a focal point for certain figures of the Zionist movement, it is nevertheless true that its history did begin before that time, and that it was not always so tightly bound to that of its famous party wall.

How, then, did the Maghrebi Quarter begin? After conquering the city in 1187, Saladin repopulated it with Muslims, particularly the largely abandoned southern outskirts. ‘Control of religious endowments was a fundamental leveraging tool in the service of the imperial government, particularly in a strategic city like Jerusalem,’ Lemire writes. As part of this imperial project, Saladin established several religious establishments to welcome Maghrebi pilgrims, including an oratory on the Haram al-Sharif and a madrassa devoted to the teachings of Maliki law, the dominant school of jurisprudence in the Maghreb.

Nothing was unprecedented here, since Jerusalem has always been rebuilt and repopulated by the contribution of exogenous populations wishing to settle as close as possible to monotheism’s sacred sanctuaries. What is more surprising is that this assembly of waqfs (religious endowments) was still functioning in the Ottoman era, the British Mandate, and the Jordanian period…and right up to the moment when the quarter was demolished in June 1967.

Here the book disappoints. I was hoping for an extensive history of the life of the quarter, but less than 50 pages of the book are devoted to its pre-twentieth century history, with over 200 pages on the twentieth century. In other words, despite the pretences of its subtitle and the emphasis on the long durée, what really interests Lemire is the neighbourhood’s destruction.

He provides a detailed and convincing explanation of the events that led to the demolition, proving that the decision was taken by the Israeli government. But at no point does he acknowledge that this was done in response to a fundamentally unfair situation whereby Muslims were able to pray at their holiest place in the city (on top of the Jewish holy place which stood there roughly 700 years prior before being destroyed by an imperialist army following a nationalist revolt), and the Christians were able to pray at their holiest place, while the Jews were left with a wall that originally never had any particular religious significance, and was itself adjacent to a neighbourhood whose residents – at the very least – did not let them pray there unmolested. The significance of the Western Wall for Jews came about largely due to a fundamentally unjust situation, whereby successive imperial rulers of Jerusalem – Pagan, Christian, and Muslim – mostly denied the Jews the right to pray at their holiest site, indeed the traditional wellspring of Jewish experience, even though it had existed prior to each of their conquests of the city.

And there was, of course, a fairer solution that wouldn’t have necessitated the destruction of an entire neighbourhood – setting aside a small portion of the Al-Aqsa/Temple Mount area for Jewish prayer. It is a massive complex, and this could have been done without much inconvenience to anyone, but this option was never on the table for the simple reason that any kind of ecumenical arrangement at Al-Aqsa is completely abhorrent to the Muslim world and would probably have led to war. Even today, when notions of restorative justice are common – particularly for resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – this idea is viewed as anathema.

The failure to even mention this essential background makes it very difficult to stomach the moral lessons that Lemire insists on delivering. At the end of my ‘Power and Powerlessness in the Old City’ tour, while sitting at the Western Wall Plaza, where the Maghrabi Quarter once stood, I asked my participants to imagine what they would have done had they been in power in 1967. It was fascinating to see the imaginative solutions they came up with, which included time-share arrangements, new divisions of the space, or leaving the status quo unaltered, and even more fascinating to see how they all acknowledged that the pre-1967 realities were obviously unjust and needed repair in some way. The destruction of the Maghrabi Quarter and the rich aspects of Jerusalem’s history it represented was undoubtedly tragic, but its origins can only be understood by learning about the disempowerment of Jews in their ancestral city, a disempowerment that those who preach (often correctly) about present-day inequalities seem completely undisturbed by.