At the time of another episode in the Israel-Hamas conflict, Operation Protective Edge in 2014, Amos Oz opened an interview with the German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle by posing two questions. First: ‘What would you do if your neighbour across the street sits down on the balcony, puts his little boy on his lap and starts shooting machine gun fire into your nursery?’ Second: ‘What would you do if your neighbour across the street digs a tunnel from his nursery to your nursery in order to blow up your home or in order to kidnap your family?’

The point was plain enough. Oz supported Israel going into Gaza, though only in the form of a ‘limited military response and not unlimited military response’. ‘Destroy the tunnels wherever they come from, and try to hit strictly Hamas targets and no other targets’, he said. In such a scenario, there would be ‘no way in the world to avoid civilian casualties among the Palestinians’, Oz acknowledged. As such, he cautioned that military intervention in Gaza would be ‘a lose-lose-situation. The more Israeli casualties, the better it is for Hamas. The more Palestinian civilian casualties, the better it is for Hamas’.

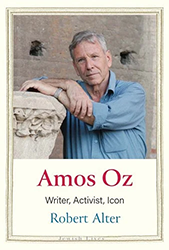

‘From the time Amos Oz came of age, he was passionately engaged in the nature and future of his troubled country’, the preeminent scholar of Hebrew literature Robert Alter writes in the first English-language biography of Oz, Amos Oz: Writer, Activist, Icon, published under the auspices of the Yale Jewish Lives series. This slender yet perceptive book—born of Alter’s close readings of Oz’s work, half a century of friendship with the author, and conversations with his wife, Nily, and a few others who knew him—attempts, among other things, to understand what compelled him to assume the role of a public intellectual.

As Oz himself acknowledged, it is common enough for Israeli writers to be engaged in public life. ‘Here in Israel, writers pretty much enjoy the social status which film stars have in other countries’, he said in a 1990 interview. But ‘in the sheer quantity of published pieces’—and there were times when Oz was writing two opinion pieces a week—‘Amos probably goes beyond’ his contemporaries in terms of his involvement in the public realm, Alter writes. His impression, too, ‘is that [Oz] rarely turned down an invitation to speak on the issues, whether in academic settings, at public affairs institutions, or for popular audiences’ both at home and abroad, though ‘Israel itself was the real theatre of his political activism’.

Oz felt, Alter writes, an ‘urgent necessity to persuade through both the written and the spoken word’. The ‘driving force of his lifelong dedication to political activism’ was his view that ‘Jews must have a national home [and] that they cannot dispense with their shared culture and their shared social reality’—whatever the cost. He was a ‘staunch advocate of the existential necessity of pluralism in Israel’s national life’. Oz also ‘devoted countless hours and great stores of energy to public advocacy for the cause of peace with the Palestinians’. His conscience, Alter goes on, ‘compelled him to engage in the enterprise of public advocacy for a two-state solution, so he had no choice but to engage, for his conscience, unlike that of many writers in the West, was entwined with the fate of the nation’.

Those, then, are the political and moral reasons for Oz’s public engagement. But his desire to go beyond the written to the spoken word also stemmed from his need for an audience, Alter thinks. Better in groups than in one-on-one situations (other than with a few select intimates like David Grossman), to observe Oz at a public event was to see him ‘delight in charming his audience, in entertaining them as he convey[ed] ideas … that were important to him’. He had a gift for public speaking: for ‘getting across what he wanted to say through lively, concrete, and often examples’. The image of Israelis and Palestinians needing not a honeymoon but rather a divorce, for instance, is one that has become part of both English and Hebrew political lexicon.

This craving for a crowd, Alter believes, goes back to his childhood: his ‘doting but problematic parents’ who ‘used to trot out their precocious and attractive only child to display his talents before guests’, thereby ‘imprint[ing] on him the role of performer’ as well as ‘performance as a default mode for relating to people’. Alter continues: ‘It is a role for which he had a natural gift, but he sensed that it was, in his own phrase, a masquerade. He could charm, he could entertain, he could seduce, and exerting that skill had an intoxicating effect on him’. Ultimately, thinking about his childhood, Alter concludes that ‘the engaging public person proves to be a tragic figure’, plagued as he was by ‘doubts about his self-worth’ and ‘haunted by the trauma of his childhood’:

If the outwardly visible person constantly sought … to be liked and admired, the subterranean self was not merely plagued by demons but felt that he was not worthy of admiration. What played a crucial role in this feeling, as in so much else, was his mother’s suicide. Even though he had summoned the courage to imagine that terrible act as a writer, it continued to haunt him till the very end.

Alter adopts a different tack with ‘Amos Oz’, eschewing doorstop comprehensiveness for a shorter but nonetheless complex and considered portrait of the person. This is to the book’s credit, though other creative decisions bear further consideration. In an introductory note, Alter explains there are no footnotes in his biography as his sources were either ‘oral communications’ or published works in Hebrew. ‘References to them would not have been of much use to English readers’, he writes. True enough, perhaps, though a judgment surely best left to the reader themselves. Alter also elected to use his own translations of Oz’s works, which feel more precise though lack the fluent musicality of Nicholas de Lange’s English renderings.

‘In the end, Amos Oz may have been more concerned with his legacy as a spokesperson for peace and reconciliation than as a writer of fiction’, Alter supposes. Oz’s view on Hamas was that it was not an organisation that could be compromised with. He told Deutsche Welle: ‘Even a man of compromise cannot approach Hamas and say: “Maybe we meet halfway and Israel only exists on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays”’. In an essay re-printed in ‘Israel, Palestine and Peace’ (1994), he wrote that Hamas ‘do all in their power to prevent the Israel/Arab war from being resolved through compromise; they do all they can to turn it into a religious war between Judaism and Islam—till the very last drop of blood has been shed’. That now includes the blood of 1,400 Israeli victims slaughtered at music festivals and on their kibbutzim.

The problem of Hamas, however, as Oz also explained in a 2010 op-ed in the New York Times, is that it is ‘not just a terrorist organization. Hamas is an idea, a desperate and fanatical idea that grew out of the desolation and frustration of many Palestinians. No idea has ever been defeated by force. To defeat an idea, you have to offer a better idea, a more attractive and acceptable one’. This echoes something the Palestinian scholar Rashid Khalidi said in a recent interview with the Spanish newspaper El País: that while ‘destroying its military capabilities is possible’, ‘destroying Hamas as an idea’ is ‘impossible’.

That better, more attractive idea was the one Oz fought for from the time of the Six Day War until his death in December 2018, as Alter emphasises in his biography. ‘My suggestion is to approach Abu Mazen’, Oz told Deutsche Welle, and pursue anew ‘a two-state-solution and coexistence between Israel and the West Bank’. He continued, ‘When Ramallah and Nablus on the West Bank live on in prosperity and freedom, I believe that the people in Gaza will sooner or later do to Hamas what the people of Romania did to Ceausescu’.

‘In our view, it has to be a two-state solution’, U.S. president Joe Biden said October 25, indicating the direction of American foreign policy when Israeli operations in Gaza are concluded: ‘And that means a concentrated effort for all the parties to put us on a path toward peace’. ‘The word compromise has a terrible reputation’, Oz said in a 2002 address collected in ‘How to Cure a Fanatic’ (2012). ‘Not in my vocabulary. For me the world compromise means life. And the opposite of compromise is not idealism, not devotion; the opposite of compromise is fanaticism and death’.