In 2006, the Iranian newspaper Hamshahri announced an ‘International Holocaust Cartoon Contest’ as an outraged riposte to the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten printing cartoons of Muhammed. The entries to the competition were as vile as you would imagine. In response, two Israeli artists, Eyal Zusman and Amitai Sandy, announced an international antisemitic cartoons contest. As Sandy defiantly announced: ‘We’ll show the world we can do the best, sharpest, most offensive Jew hating cartoons ever published! No Iranian will beat us on our home turf!’

The concept was so delicious that the outrageous entrants even included one from the brilliantly caustic US cartoonist Eli Valley, whose defiant anti-Zionism might otherwise have precluded him from joining in with an Israeli-based project. The contest demonstrated an irreverent side to Israel that was hard even for diasporist critics not to love.

It was that side of Israel that I had hoped to encounter in Colin Shindler’s Israel: A History in 100 Cartoons. Sadly, I was to be disappointed.

Shindler does mention the antisemitic cartoon contest in passing. His book contains an introductory essay that provides some background on political cartoons in Israel and, more broadly, the role they play in politics. He has certainly done his homework (this was a lockdown passion project) and credits the Israel Cartoon Museum in Holon for their assistance.

Although not marketed as a textbook, the volume is an informative primer in Israeli history. Its year-by-year and decade-by-decade structure offers a condensed yet comprehensive timeline and even experienced Israel-watchers (and Israelis for that matter) will find something they didn’t previously know about. Every year and every decade has a short chapter devoted to it, beginning with a contemporary cartoon commenting on a particular incident or episode in Israeli political history. Shindler patiently explains the references and provides a translation of any text he finds in the cartoon.

After a chapter on the pre-history of Zionism, including some interesting caricatures of Jabotinsky, Ben-Gurion and the like, Shindler’s cartoon history of the post-independence state begins in 1949, with Yossi Ross’s depiction of an orthodox Jew casting his vote in the first Israeli election, wrapped in a prayer shawl and captioned with the words of the shehecheyanu blessing (which thanks the almighty for living to see the day). We end in 2020, with Zach Cohen depicting blithely oblivious consumers riding an escalator into the mouth of a giant Covid virus holding up a ‘sale’ sign. In between, Shindler offers a selection of cartoon commentaries on everything from historical events that will be remembered for decades and internecine cabinet quarrels whose specifics are rapidly fading from memory.

So why the disappointment? The book certainly works pedagogically and, if I taught an undergraduate course on Israeli history I would happily assign it to students. The problem is more that the book’s use of cartoons as didactic device means that much of their aesthetic and social significance is elided, regardless of Shindler’s intentions. The author has a heavy preference for the kinds of cartoons that depict a situation metaphorically while also including captions to ensure no reference is lost. So the 1967 Israeli victory in the Six Day War is illustrated by Dosh’s cartoon of his Israeli everyman Srulik, climbing out of shark-infested waters labelled ‘the situation before’ onto a sunlit cliff labelled ‘security and peace’.

Cartoons like this are useful teaching aids but – aside from rarely being amusing – this can lead readers to forget that they are also active, short-term interventions in the situation that they themselves depict. Similarly, while Shindler’s introductions do discuss the history of Israeli cartoons, in practice in the main text they tend to be treated as epiphenomenal to the ‘real’ stuff of history. This is not a history of Israeli visual aesthetics, nor of Israeli humour, nor of Israeli media culture as it intersects with political history. The book makes it too easy to forget that art itself has agency.

It doesn’t help that most of the examples in the book are from mainstream Israeli publications. From the evidence here the Israeli press lacks a cartoonist with the scabrous venom of a Steve Bell. Of course, that implies Israeli press cartoonists don’t – as Bell sometimes does – confuse brutal satire for outright racism. That immediately makes me suspicious. The history of British post-war press cartoons is full of racism and antisemitism. Can the Israeli press really be so (comparatively) anodyne?

And there is nothing here from Israeli Arabic publications, from the Haredi community, from the far right or the far left. A few years ago I purchased an extraordinary collection of Israeli anarcho-punk flyers and pamphlets called It’s All Lies and this is part of Israeli cartoon history too. So whilst I haven’t done the research that Colin Shindler has done I was left wondering at what he left out.

The limited scope of the cartoons on show in the book and the narrow illustrative function that they serve, means that readers only dimly experience Israeli political life in all its rumbustious vitality, its visceral hatreds and passionate idealism.

Still, there are cartoons in this book that stand out, that avoid pedantic labelling in favour of exploring the medium to the fullest. My favourite one in the book is by Arie Davon and appeared in Davar in 1962. It comments on the kidnapping of eight-year-old Yossele Schumacher by his Hassidic grandparents who, concerned about his lack of religious upbringing, smuggled him to New York. He was located by the Mossad in 1962 and Navon’s cartoon depicts the desperate search by Schumacher’s mother Ida. She is lost in a forest of Hassidic men, depicted as inhuman tree-like scarecrows, completely indifferent to her plight. There is no pedantic labelling of the characters, no leaden metaphor, just a raw, empathetic representation of anger and grief.

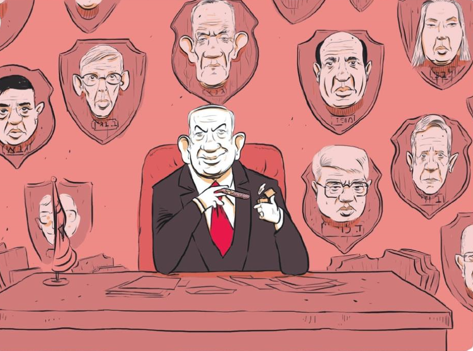

The winner of the Israeli antisemitic cartoons contest, ‘Fiddler on the roof’ by Aron Katz, showed said uber-Jewish fiddler playing on top of the Brooklyn Bridge during the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center. Shindler’s choice for 2001, by Ze’ev in Haaretz, entitled ‘Unity Government’, depicts Ariel Sharon carrying a sheep labelled ‘Labour’ to the slaughter. The latter is neither antisemitic nor offensive and it provides a handy way of learning about the Israeli elections in that year. But the former exudes a mischievous vitality that no amount of laboured metaphor can hope to match.