Philip Earl Steele examines the contribution of Reverend William Hechler to the early Zionist movement and argues that Hechler’s career was an outstanding example of how deeply intertwined were the efforts of both Jews and Christians to restore Israel. This is the third of Steele’s deep dives into British Christian Zionism, having previously explored George Eliot’s inspirational role in the emergence of Hovevei Zion, and the diplomatic and direct organisational efforts of Laurence Oliphant in the First Aliya. Steele’s full scholarship on these three British Christian Zionists is also available in Polish.

INTRODUCTION

The Anglican priest William Hechler (1845-1931) was a significant figure in the efforts of British Christian Zionists to foster the First Aliya, born of the Hovevei Zion movement in the early 1880s. Sent as an envoy of the Protestant Association in May 1882 to Ukrainian lands during the refugee crisis resulting from the pogroms of 1881/82, Hechler met with Leon Pinsker in Odessa several months before Autoemancipation was published in September 1882 and influenced his ‘territorial nationalism’. Reverend Hechler also met with leaders of the Zionist youth organisation BILU there, and that same summer published an important tract in England on the imminent ‘Restoration of the Jews’. Yet Hechler went on to have an even greater role in the Zionist movement through his support of Theodor Herzl, whom he met in Vienna just weeks after Der Judenstaat was published in 1896.

Like Laurence Oliphant, who was born in Cape Town in what is now South Africa, William Hechler (1845-1931) was also born far from the British Isles – namely, in Benares in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. As a young man, his father Dietrich, a native of Baden, Germany, had moved to England, where he studied at an Anglican seminary and became a missionary pastor. He married an Englishwoman, Catherine Palmer, and shortly after their wedding the young couple travelled with the Christian Missionary Society to British India. Their life in the Raj began in 1844. In October the following year their first child was born: William Henry Hechler.

Meanwhile, it so happened that Oliphant’s first independent trip – in the winter of 1850/1851 – was with the ruler of Nepal, Jung Bahadur, to none other than Benares, where Oliphant made the rounds among the European community resident there. Was the 21-year-old Laurence introduced to the 5-year-old William while in Benares? Perhaps so – but whatever the case, the two men’s paths were somehow never to cross again. Though overlap they did, as both men were steeped in Evangelical Protestantism and its theology of recognizing modern Jews as the Biblical Israelites and affirming that God’s ancient covenant with them remains valid. Thus, scholars sharply distinguish Evangelicalism’s ‘teaching of esteem’ from the Catholic church’s former ‘teaching of contempt’ – which was overturned not until the Second Vatican Council’s document Nostra Aetate in 1965, a stance made clearer in 2013’s Evangelii Gaudium: ‘We hold the Jewish people in special regard because their covenant with God has never been revoked’. However, today’s Catholic doctrine is not Zionist, whereas Evangelical doctrine continues to be so.

When he was six years old, William left India with his father and two sisters (his mother had died in the summer of 1850) and travelled to Baden, where Dietrich Hechler, an ardent philosemite and scholar of Biblical prophecy, became associated with the London Society for the Jews (LSJ) headed by Lord Shaftesbury, one of 19th-century Britain’s most significant Christian Zionists. Shortly thereafter, young William began attending the Christian Missionary Society school in London (Islington). He also went on to study there at the Christian Missionary College.

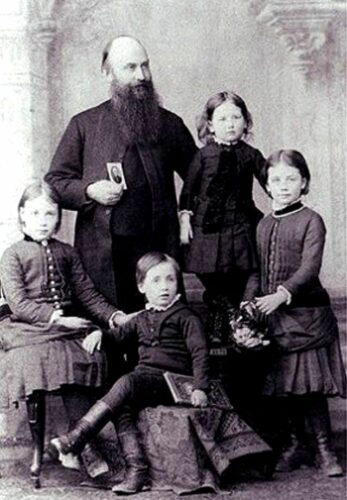

In 1870 Hechler was ordained an Anglican minister. He was sent on his first missionary post to Lagos, Nigeria, but malaria soon forced him to return to Karlsruhe in Baden, where his father had again been working since 1865. There William won a job teaching the children of Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden. From 1876 he was in Ireland, where he married Henrietta Huggins and worked in County Cork for four years before taking up a post in London with the Church Pastoral Aid Society. During his early years with the CPAS he produced two important written works. The first was an article entitled ‘The Restoration of the Jews’ published in June 1882, although in fact Hechler had been handing it out since January that year as a broadsheet (i.e., a one-page pamphlet in newspaper format) among members of the LSJ and sundry prayer groups. In August 1883 he completed a documentary history of the Anglican-Lutheran bishopric in Jerusalem founded jointly in 1841 by England and Prussia. Scholars surmise that this may have been part of a bid to become Jerusalem’s bishop himself, following bishop Joseph Barclay’s death in October 1881 and the ensuing, prolonged vacancy. Whatever the case, in June 1885, Hechler became the chaplain at the British Embassy in Vienna – keeping that post for 25 years, until retirement in June 1910 when he moved to London.

HECHLER AND HOVEVEI ZION

As a result of the widespread pogroms of 1881-1882 in western Russia, not only the Alliance Israélite Universelle and Mansion House sent representatives to Habsburg eastern Galicia, where a swelling number of Jewish refugees found safe haven (as described in part two of this series). On 24 February 1882, at the London headquarters of the Protestant Association, a meeting took place that was similar to the one held by Mansion House a few weeks earlier. It differed, however, in that it explicitly referred to Jews ‘who were desirous of emigrating to Palestine as agriculturalists. It was their wish to go to Gilead, as this was deemed the best spot for such work’. As Donald M. Lewis writes, ‘A resolution in support of this group […was] moved by the Rev. Mr. William Hechler, and when a relief committee was formed [for what was called the Syrian Colonisation Fund], Shaftesbury was the President and Hechler the key activist’.

Hechler’s role at the meeting had come about in part by happenstance. As he explained at the time in a published letter, in mid-February 1882, while returning by train from Cologne to London, ‘in the same railway carriage with me sat … a descendant of Abraham’ who turned out to be from Russia and had been ‘sent as a deputy by some 200 to 300 Jews, representing 25 families, to appeal for help to enable them to settle in Palestine’. These Jews had evidently been impressed by Laurence Oliphant’s recent efforts with the Sultan and had therefore sent a representative to London. This is made clear by their intention to settle in the Biblical land of Gilead, which Oliphant had chosen as the site of his plan for Jewish settlement in Palestine, most fully elaborated in his book The Land of Gilead, published in December 1880. As newspaper articles reporting on the 24 February meeting in London explain, the name of the Jewish envoy whom Hechler met was Niesen Rappaport and he came from Mogilev, in today’s Belarus. Having been invited by Hechler to attend the Protestant Association’s meeting, Rappaport described through an interpreter the terrible situation of the victims of the pogroms. As The Daily Telegraph reported on 25 February 1882, ‘Reverend William Henry Hechler, who fell in with Mr. Rappaport penniless in Coln [sic], read the translation of a letter that gentleman carried, which was signed by the Rabbi of Mohileff [sic] and 34 heads of families there resident, representing 220 persons’. The Globe (also on 25 Feb. 1882) added, ‘The Rev. Mr. Heckler [sic], the Rev. Dr. Laseron, and the Rev. Mr. Stern supported the resolution [to help the group from Mogilev] which was unanimously adopted’.

Meanwhile in Palestine, the Protestant Association’s related organisation – the aforementioned London Society for the Jews (LSJ) – struggled, as Lewis writes, with ‘the flood of desperate Russian immigrants […] at its center in Jaffa […] and at its Sanatorium in Jerusalem. […] The LSJ workers responded so generously that the Jerusalem mission station was soon near financial collapse and had to be bailed out by the London committee. In England, the LSJ established a ‘Committee on the Persecution of the Jews in Russia’ […with which] the Reverend William Henry Hechler […] worked closely […] to resettle these refugees in Palestine. Later in 1882, he was dispatched by the committee to investigate what was happening in Russia’.

HECHLER AND PINSKER

Hechler set out for today’s Ukraine in mid-May, 1882 – alone. Which is to stress that, as opposed to how many secondary sources present the matter, Hechler was not accompanying Oliphant. His most important destination was Odessa, but he also visited Mogilev (the town of Niesen Rappaport), Kishinev and Balta, as his later friend Nahum Sokolow reported in History of Zionism, 1600-1918. In Odessa Hechler met with Leon Pinsker, who had just returned from a spring tour of Western European capitals (Vienna, Berlin, Paris, London), during which time he had discussed with Jewish leaders the pogroms still in progress – and above all presented his ideas on a remedy. Pinsker showed Hechler the German-language manuscript of Autoemancipation, which was published several months later, in September, 1882. In the draft of that foundational work of early Zionism, Pinsker argued that the Jews needed their own homeland, but he didn’t specify where. Hechler earnestly pleaded with him that the only fitting place for a restored Israel was Palestine, and he based his conviction on Biblical prophecy. As Paul C. Merkley wrote, Hechler ‘took out his Bible and found the passages in Amos, Jeremiah, and Isaiah, and elsewhere that made clear God’s plan to bring the diaspora to Jerusalem’. In all likelihood Hechler also discussed with Pinsker the LSJ’s recent settlement activities in Palestine and assured him that enormous financial support for a Jewish Palestine could be expected from English and German Protestants. From press reports Pinsker was already familiar with Oliphant’s similar argument, and in fact Pinsker would soon seek direct contact with Oliphant. Lastly, Pinsker was no doubt also impressed by a letter the Anglican clergyman carried with him – namely, one from Queen Victoria addressed to Sultan Abdul Hamid II. In it the British monarch is to have asked for permission for Jewish settlement in Palestine.

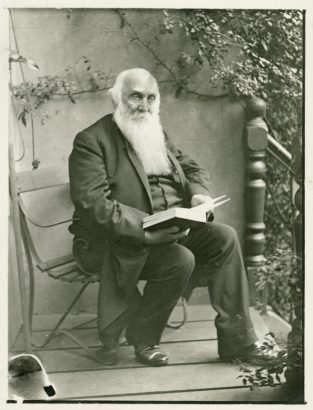

[William Hechler. Photo courtesy of author]

Hechler claimed to have influenced Autoemancipation’s published form, in which Pinsker did express qualified favour for Palestine as the territorial homeland for the Jews. The passage, ‘Perhaps the Holy Land will again become ours. If so, all the better’, certainly has the ring of a concession made in debate – and thus may be attributable to the Anglican’s influence. Nevertheless, Pinsker went on to stress that the Jewish homeland he was calling for need not necessarily arise in Palestine: it might also arise in North America. As we know from the history of the Hovevei Zion movement, of which Pinsker became one of the pre-eminent leaders, his sights were indeed to settle ever more squarely on Palestine. It is therefore reasonable to infer that Pinsker’s contact with Hechler and knowledge of Oliphant’s strivings reinforced the efforts of his close collaborators Moshe Lilienblum and rabbi Samuel Mohilever to convince him of Palestine.

During his stay in Odessa, Hechler also established contacts with the leadership of BILU, the organisation of young Russian Jews (many of them students) who were earnestly organising to go to Palestine as pioneers. A letter sent on 6 June 1882 by the BILU Central Office in Odessa to Vladimir Eisemann, who was in Istanbul, stated that Reverend Hechler was ‘pleasantly surprised’ by the existence of the movement and that he would soon be travelling to the Turkish capital.

Nonetheless, there is no clarity about Hechler’s activities in Istanbul in June 1882 – nor even about the fate of Queen Victoria’s letter, with some scholars doubting its existence. Though it is true that in mid-August the mouth-piece of the Hovevei Zion movement – i.e., the Hebrew-language weekly Ha-Magid, headed by David Gordon in today’s Ełk, Poland – did publish a piece stating that Rev. Hechler ‘had shaken heaven and earth and gone to high places to awaken a feeling of compassion for the Jews’.

‘THE RESTORATION OF THE JEWS’

What is best known about Hechler from that June regards London, where his pamphlet entitled ‘The Restoration of the Jews’ was published in the journal The Prophetic News and Israel’s Watchman. In five short chapters he outlined the typical evangelical thinking of the day on the restoration of Israel – albeit with one very significant exception: in Chapter III, Section 9, he explained that ‘With reference to the conversion of the Jews – a) Some passages [of the Bible] speak of their conversion before the restoration [here he cites several verses] b) Other passages, however, state that their conversion will follow after the restoration’ (here, too, he cites several). Hechler adds in Section 10: ‘From these passages we conclude that some [of the Jews] return, believing in Jesus, their Messiah; whilst others will see their error only at the sight of the Messiah’. In other words, Hechler treated the issue of conversion as irrelevant to the Jewish resettlement of Palestine. It is also important to note that in Chapter IV, Hechler referred to the recent pogroms in Russia as signs and foreshadowings of the coming Restoration. Moreover, in the fifth and final chapter of his text – ‘Our Duty’ – Reverend Hechler emphasised that ‘The duty of every Christian is to … LOVE THE JEWS … for they are still beloved for their fathers’ sakes’, adding, ‘Blessed shall that nation be which loves the Jews; for God promised to Abraham and his children, “I will bless them that bless thee.”’ [All italics and capitalisations from the original.]

‘THE PRINCE AND THE PROPHET’

Reverend Hechler was to become one of Theodor Herzl’s closest associates, and thereby he played a crucial role in the early history of Zionism. One measure: Herzl refers to Hechler by name in his diaries more than 120 times. Just how meaningful Hechler was to Herzl was described in 1929 by Maurice Samuel in the volume Theodor Herzl: A Memorial, compiled for the 25th anniversary of Herzl’s passing:

Herzl himself calmly records that one of his chief worries at the first Congress was to prevent his feeble left hand from knowing what his feeble right hand was doing. He was afraid that Hechler and [Philip Michael] Newlinsky might discover that they were, in fact, the Zionist movement apart from the Congress. The first was a priest and a dreamer, sunk in cabbalistic calculations of the end of all things, and convinced by Prophetic Tables dated at the beginning of the Mohammedan era that the time of the Jewish return was at hand; the second was a Polish nobleman in Galuth, a winning adventurer, a landless and penniless weaver of intangible international intrigues. They and Herzl – die drei Helden von Schem – started that Zionist movement on its fabulous international career. Such are the mechanics of the first days of the movement.

The chaplain at the British Embassy in Vienna, Rev. William Hechler, announced himself at the home of the author of Der Judenstaat on 10 March 1896. Herzl described the figure he then encountered as ‘a likeable, sensitive man with the long grey beard of a prophet’ who explained to him that he considered his work (published a few weeks earlier on 14 February) to be the fulfilment of prophecy, and offered to open the door for him to the German royal family. Hechler explained to Herzl what we already know – that he had been the teacher of the children of Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden, adding that he also knew his nephew, Kaiser Wilhelm II. Hechler was swift to act: already on 23 April 1896, the first of a series of meetings between Herzl and the Grand Duke took place in Karlsruhe, the capital of Baden. Thus was the Hungarian Zionist ushered onto the international stage. Having been won over to the plans for a Jewish State in Palestine – as we shall see, every bit as much by Hechler as Herzl himself – the Grand Duke agreed to open the door for him the Kaiser. This bid finally came to fruition in Istanbul (Yıldız) on 18 October 1898. Ten days later at Mikveh Israel in Palestine, Herzl stood hat in hand to greet the Kaiser, who was mounted on horseback. Wilhelm II reached down smiling to shake Herzl’s hand, exchanged pleasantries with him, and then again gave him his hand before riding off – an honour that left everyone murmuring. The two men and their advisors met yet a third time in Jerusalem five days later (Nov. 2, 1898) for proper talks, albeit ones that mysteriously failed. During both occasions in Palestine, Rev. Hechler was present with Herzl on what was to be the latter’s only trip to Eretz Israel.

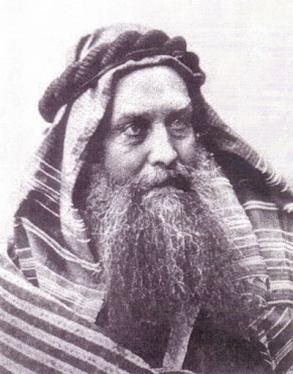

[William Hechler. Photo courtesy of author]

And so it was not Germany, as we know, but Great Britain that continued making steps toward fostering the creation of modern Israel. Not that the efforts vis-à-vis the Kaiser were wasted – they of course created excellent PR and thus further elevated both the Zionist cause and Herzl’s person in Europe. But the unceremonious collapse of talks in Jerusalem left Theodor reeling. After all, the initial meeting in Yıldız had been so extremely promising. The nearly three-hour discussion with the Kaiser, which Herzl at length recorded in his diary over the following days shipboard to Jaffa, ended so optimistically – with Kaiser Wilhelm II promising Herzl over a handshake that he would intercede with the Sultan and ask for ‘a Chartered Company under German protection’ – that Herzl was stirred to a vision. ‘I had the magic-forest sensation’, he wrote in one of two accounts of the experience, ‘of encountering the fabulous unicorn which said with a human voice “I am the fabled unicorn”’.

HERZL’S FAILING

Theodor Herzl adopted a high-minded tolerance toward eccentricity in the case of ‘the good Hechler’s’ focus on Biblical prophesies and their fulfilment. Likewise, Herzl also shielded himself from the fact that Protestant concepts regarding the prophesied Restoration of Israel operated powerfully in the mind of the Grand Duke. His diary contains little more than glimmerings of understanding as regards this aspect of Frederick I’s thinking. For instance, about their first meeting in Karlsruhe, Herzl wrote that once he had presented his case in full, ‘Hechler took the floor … and discoursed on the imminent fulfilment of the prophecy. The Grand Duke’, Herzl observed, ‘listened silently, magnificently, and full of faith, with a strikingly peaceful look in his fine, steady eyes. Finally he said something that he had said several times before: “I should like to see it come about. I believe it will be a blessing for many human beings”’.

At the broader level, this raises one of Herzl’s greatest failings – i.e., his inability to discern Zionism’s natural ally in Evangelicalism and thereby to devise a strategy of ‘faith-based diplomacy’, as we would put it today. Specifically, however, what this case underlines is that Herzl preferred to keep himself unaware of the deeply religious nature of Rev. Hechler’s conversations with the Grand Duke regarding Zionism – though it’s true that their written exchanges came to light not until Hermann and Bessi Ellern discovered them in 1959 and 1960.

In the Introduction to the published facsimiles of the correspondence between Herzl, Hechler, the Grand Duke and the German Emperor, as the Ellerns’ book is titled, Alex Bein, one of Herzl’s biographers, wrote: ‘The intermingling, here, of Christian calculations of the end of days, the second advent and the return of Israel to the Holy Land, is to our minds astonishing. Already in his first letter to the Duke [26 March 1896], Hechler renders an account of his abstruse computations according to which the Redemption must take a new course from the years 1897-1898. He regards Herzl as an instrument in the hands of Divine Providence, unfaltering though modest in fulfilling his role, though he himself is unaware of his part in the divine plan. From the letters we see that it was this religious approach … that appealed most to the Duke [italics mine]’.

Though the Kaiser was less religiously-minded than the Grand Duke, he did frame ‘the Jewish question’ theologically – though by no means was his theology Evangelical or Pietist, as in the case of Frederick I. Rather, it was steeped in the antisemitism then known to Catholicism and mainline Lutheranism. Hence, having expressed his support of Zionism in the famous letter to his uncle the Grand Duke dated 29 September 1898, the Kaiser at once clarified that it was after all not his responsibility as emperor to pursue revenge against the Jews because ‘they killed Jesus’. ‘Thou shalt love thy enemy’, he declared, adding, ‘Make friends even with unjust Mammon’.

Also worth noting is that Wilhelm II’s imaginarium was furnished with various Biblical literalisms, as we see in how he was willing to entertain conjoining his trip to Jerusalem in November 1898 with a search for the Ark of the Covenant. As Alex Bein noted in 1961: ‘The connection established by both Hechler and the Grand Duke between a purely political matter and the quest for the Ark of the Covenant – about which a number of articles had been published at the time in Die Welt – is an entirely new revelation.’

THE FIRST ZIONIST CONGRESS

In the meantime, over a year earlier in late August 1897, the First Zionist Congress had been held in Basel, Switzerland. In the spring of 1896, during the run-up to the Congress, Hechler had republished in Vienna his broadsheet ‘The Restoration of the Jews’ in a German translation that dismissed the question of conversion even further than had the English original. On the eve of the Congress, Hechler offered a lengthy testimony in the second edition of the new Zionist newspaper, Die Welt (11 June 1897). Entitled, ‘Christen über die Judenfrage’ (Christians on the Jewish Question), it amply referenced Bible passages and sundry prophecies, and included this ringing declaration:

As a Christian, I believe in the Jewish National Movement called ‘Zionism’ because, according to the Bible, yes, according to the ancient Hebrew prophets themselves, a Jewish State must once again arise in Palestine. And, as it seems to me, judging by the signs of the times the Jews will again soon occupy their own beloved home in their ancient G-d given Fatherland. May they soon respond to the call.

Hechler signed his testimony in Die Welt, ‘William Henry Hechler, Chaplain to Her Britannic Majesty’s Embassy in Vienna’.

At the Congress itself, the Anglican clergyman was a guest of honour. At the closing session, Herzl thanked him publicly among other ‘Christian Zionists’ (including – albeit in absentia – Henry Dunant, founder of the Red Cross), in what seems to be the first use of the label. Hechler also attended subsequent Congresses, and was immortalised by Herzl in his novel Altneuland, published in October, 1902, as the character Reverend Hopkins. Less than two years later, in July 1904, Hechler was one of the people keeping vigil at his friend’s deathbed in the Austrian mountains.

HECHLER AND SOKOLOW

William Hechler’s career offers an outstanding example of how deeply intertwined were the efforts of both Jews and Christians to restore Israel. And how broadly intertwined, as well. For besides his relations with Pinsker and Herzl, Rev. Hechler also became a valuable ally to Nahum Sokolow, as alluded to above. Their acquaintance began in the summer of 1912 when Sokolow – who later, having become the head of both the World Zionist Organization and the Jewish Agency for Palestine, was dubbed ‘the most important Jew in the world’ – visited London. As Sokolow’s son Florian wrote in his Polish-language biography of his father, Hechler enthusiastically helped Sokolow make the contacts in Anglican circles he sought, knowing (in sharp contrast to Herzl) how important Evangelical beliefs concerning the Jewish world were to the Zionist cause.

An especially memorable encounter that Nahum Sokolow owed to Hechler took place at the home of one Rev. William Henry Baptist Proby, a prominent Bible scholar. Florian Sokolow describes how Proby, Hechler, and his father entered into a passionate discussion on Old Testament arcana, almost forgetting their meeting was to focus on Zionism’s challenges. When Sokolow did, at long last, manage to turn to the Zionist movement, ‘the old theologian Proby was so moved that he rose up out of his chair and started to fervently pray, and Rev. Hechler right along with him. It was a sight my father would never forget. Two venerable pastors awash in tears, calling upon the grace of God for the success of his mission in England. He was at once transported back to his childhood and youth in Wyszogród, Płock and Maków in Poland. The sagely theologians, each of whom resembled the author of the Torah, the pile of Hebrew works stacked on the table, the discussions of the Scriptures … for a moment my father succumbed to the illusion that he was once again standing beside his rabbis of old, his Talmudic masters’ [translation mine].

EPILOGUE

In 1929, when the volume Theodor Herzl: A Memorial was being put together, the 83-year-old Reverend Hechler agreed to share his recollections of Theodor Herzl, whose death – though now a quarter-century past – left him with some misdirected, unresolved bitterness. Below I give Hechler’s remarks in full:

It was God’s will that I should help my dear friend Dr. Theodor Herzl. That will was made manifest in my being in Vienna from the year 1885 to 1910, in a position which enabled me to bring to the attention of certain people of importance the Messianic vision of the Jewish leader.

The memory of our work together for God’s ancient people is precious and sacred to me: too sacred for me to dwell long upon it.

I was with him at the beginning of his dreams, and I was with him almost at the last moment of his earthly life.

On Saturday, July 2, 1904, I sat at his bedside, in his home at Edlach, on the Semmering mountains. I comforted him in his sickness, and I recalled the days when we had traveled together to Palestine, six years before, filled with hope and certain of early success. I told him what his own medical adviser had said to me: that he might go again with me to the Holy Land, and look again with me on Jerusalem. The sea journey would restore him to his strength and enable him to continue his labors.

But he seems to have known that there was no hope for him. He placed his right hand on his heart, and holding my right hand in his left hand, he said: Grüssen Sie Alle von mir, und sagen Sie ihnen, ich habe mein Herz-Blut für mein Volk gegeben [Greet everyone from me, and tell them I have given my lifeblood for my people].

He turned from me, then, coughing, and bringing up blood.

The next day, Sunday, July 3rd, while I was preaching in Christ Church, our British Embassy Chapel in Vienna, God took Herzl from us, for the Jews were not worthy of him. And a month later I was delivering Herzl’s dying message to his friends in the Holy Land. I deliver it again to you now, throughout all the world, twenty-five years after he gave it to me.

God bless you all.

The eighty-three-year-old pilgrim from the earthly to the heavenly.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brodeur, David D., ‘Christians in the Zionist Camp: Blackstone and Hechler’, Faith and Thought, London, 1972-3, vol. 100, no. 3, pp. 271-298.

Central Zionist Archives (CZA) in Jerusalem (AK/9).

‘Church Missionary College, Islington’, Yorkshire Gazette, June 17, 1843, p. 3.

Documents on the History of Hibbat Zion and the Settlement of Erez Israel, first compiled and edited by Alter Druyanov, revised by Shulamit Laskov, vol. 1, Tel Aviv, 1982.

Duvernoy, Claude, The Prince and The Prophet, 1966 (translation form the French by Jack Joffe, Christian Action for Israel, Jerusalem 1979).

Gidney, W.T., The History of the London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews, From 1809 to 1908, London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews, London, 1908.

Goldman, Shalom, chapter 2, ‘Theodor Herzl and his Christian Associates (1883-1904)’ in his Zeal for Zion: Christians, Jews, & the Idea of The Promised Land, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2009.

Hechler, William, ‘The Restoration of the Jews’, The Prophetic News and Israel’s Watchman, London, June, 1882, pp. 184-186.

Hechler, William, The Jerusalem Bishopric: Documents with Translations, Trübner and Co., London, 1883.

Hechler, William, ‘The First Disciple: The British Chaplain Who Aided Herzl in His Activities’, in Theodor Herzl: A Memorial, The New Palestine, 1929, pp. 51-52.

Herzl, Theodor, The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl, vol. 1-5, Raphael Patai (ed.) & Harry Zohn (translator), Herzl Press and Thomas Yoseloff, New York 1960.

Herzl, Hechler, the Grand Duke of Baden and the German Emperor, 1896-1904: Documents found by Hermann and Bessi Ellern, Reproduced in Facsimile, Ellern’s Bank Ltd., Tel Aviv, 1961.

Lambeth Palace Library in London (TAIT 290ff, TAIT 288ff, Benson 174ff).

Laskov, Shulamit, ‘The Biluim: Reality and Legend’, Studies in Zionism, Vol. 2, 1981.

Lewis, Donald M., The Origins of Christian Zionism: Lord Shaftesbury and Evangelical Support for a Jewish Homeland, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2010.

Maaß, Enzo, ‘Forgotten Prophet: William Henry Hechler and the Rise of Political Zionism’, Nordisk Judaistik, vol. 23, no. 2, 2001, pp. 157-193.

Merkley, Paul. C., The Politics of Christian Zionism, 1891–1948, Routledge, New York 1998.

‘Persecution of the Jews in Russia’, The Daily Telegraph, Feb. 25, 1882, p. 3.

‘Persecution of the Jews in Russia’, The Globe, Feb. 25, 1882, p. 6.

Pileggi, David, ‘William Hechler 1845-1931: Chronology’ and other materials, CZA, AK/9.

Pinsker, Leo, Auto-Emancipation, trans. D.S. Blondheim, revised by Arthur Saul Super, Masada Youth Zionist Organization of America, 1935.

Pinsker, Leo, Road to Freedom: Writings and Addresses, with an introduction by B. Netanyahu, Scopus Publishing Company, New York, 1944.

Salmon, Yosef, ‘Ideology and Reality in the Bilu »Aliyah«’, Harvard Ukrainian Studies Vol. 2, No. 4 (December 1978).

Samuel, Maurice, ‘Herzl’s Diaries: An Explanation which Deepens the Enigma’, in Theodor Herzl: A Memorial, The New Palestine, 1929, pp. 125-127.

Schoeps, Julius H., Pioneers of Zionism: Hess, Pinsker, Rülf, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin–Boston, 2013.

Shumsky, Dimitry, ‘Leon Pinsker and Autoemancipation!: A Reevaluation’, Jewish Social Studies: History, Culture, Society n.s. 18, no. 1 (Fall 2011): pp. 33–62.

Sokolow, Florian, Nahum Sokołów: Życie i Legenda, Księgarnia Akademicka, Kraków, 2006.

Sokolow, Nahum, History of Zionism, 1600-1918, vol. I & II, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1919.

Steele, Philip Earl, ‘British Christian Zionism (Part 1): George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda’, Fathom Journal, June 2019, https://fathomjournal.org/british-christian-zionism-and-george-eliots-daniel-deronda/

Steele, Philip Earl, ‘British Christian Zionism (Part 2): the work of Laurence Oliphant’, Fathom Journal, January 2020, https://fathomjournal.org/british-christian-zionism-part-two-the-work-of-laurence-oliphant/

Steele, Philip Earl, ‘Henry Dunant: Christian Activist, Humanitarian Visionary, and Zionist’, Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs 2018, pp. 81-96 DOI: 10.1080/ 23739770.2018.1475894.

Steele, Philip Earl, ‘Syjoniści Chrześcijańscy w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej, 1876-1884. Przyczynek do Powstania Hibbat Syjon, Pierwszego Ruchu Syjonistycznego’, in Żydzi Wschodniej Polski, Seria VII: Między Odessą A Wilnem – Wokół Idei Syjonizmu, Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, eds. Jarosław Ławski, Ewelina Feldman-Kołodziejuk, 2019, pp.105-143.

Sykes, Christopher, Two Studies in Virtue, Collins, London, 1953.

Taylor, Anne, Laurence Oliphant, 1829-1888, Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 1982.