The subtitle of this interesting memoir is ‘comfort in rootlessness’. This formulation is, as the author suggests, a response in part to a particular version of antisemitism, that pioneered by the Soviet Union after the Holocaust. takes the reader on quite a journey to explain how and why he came to feel at peace with a sense of always being something of an outsider. The feeling of being on the margins is one which many readers of this journal may recognise, as it framed the experience of many Jews across the globe for centuries.

The author grew up within the Soviet sphere of influence after the Holocaust, in Romania where he believes that he experienced no antisemitism personally. This is slightly surprising, given what had been done to Jews there in a state which was not only allied to the Nazis but perhaps the most enthusiastic collaborator in the Holocaust, the memory of which was systematically repressed by the communist regime. Antisemitism moreover was swiftly developed and was promoted by the regime, as throughout the communist bloc, but it may well be the case that, as a child, he did not perceive it directly. What lay over him though, at least to some extent, was nevertheless the shadow of the Holocaust. Even though he seems to believe still that it was a ‘non-event’ as far as his nuclear family was concerned, it certainly profoundly affected his father’s sister, who became his surrogate mother after his mother’s early death, and who invoked it almost daily, sometimes screaming and crying at night about her own mother who had been taken so violently from her. His father’s explanation, that he did not cry because men do not, was accepted by the child it seems, but there was also, as he explains, something at work here in what he calls the ‘cultural snobbishness’ of the partly assimilated Hungarian bourgeoisie to which his family belonged in Timisoara, a place that later achieved some fame as the birthplace of the revolution that swept the revolting Ceausescu clan from power in late 1989.

Long before then, Andrei had left Romania with his father, and certainly by then antisemitism had become more of a problem for them both directly. Arriving in Vienna, they experienced antisemitism in its postwar Austrian form, in a society which was (and largely remains to this day) in substantial denial about its role in the Holocaust. He was very fortunate, as he recounts, to be able to obtain an elite education there, thanks to the intervention of a teacher who bravely refused to go along with a widespread antisemitism that would otherwise have excluded him. He pays generous tribute to this individual, as he does to many friends and colleagues throughout this book. This recognition of what he owes others is one of the most attractive features of this memoir, and is not moreover confined to the professional side of his life, most obviously in the gratitude he expresses to his father, his aunt and his wife.

From Vienna he takes us to New York and his experience at Columbia in the late 1960s, the period when the New Left emerged as a significant force, among students in particular. The author was fundamentally in sympathy with this cultural and political development but never went along with all of its claims and assumptions, some of which have not stood the test of time, although tragically some of its most grievous errors can be found again, in arguably an even worse form today on too much of the left. These include a contempt for ‘bourgeois’ democracy, a wild and unreasoned hatred of the West, and of the United States in particular, and an alarming rise in antisemitism, directed not just towards Israel but towards all who identify, or support it in any way, and rightly regard the existence of a Jewish state after the Holocaust as both entirely legitimate and fundamentally necessary. The author disagreed with these postures when they were fashionable in the late 1960s, as they are again now, for a number of reasons. One was that he already knew a great deal more about Marx than many of his contemporaries, which may strike a chord with those who observe the ignorance of so many of today’s self-professed ‘Marxists’. Partly as a result, he did not share the entirely uncritical view so many had of dictators such as Ho Chi Minh and Fidel Castro who presented themselves as socialists, in ways that Marx would have found rather difficult to recognise, to put it mildly. His initial scepticism has only been confirmed over time and is indeed perhaps even more necessary today, given the way in which any regime that opposes the West, however repressive, so often gathers automatic support from many who like to see themselves as the New Left’s successors. Nor did he go along with the arrogant, patronising and contemptuous view which German radicals in particular displayed to those struggling in vain at that time to establish some kind of democratic norms in Czechoslovakia. He detected already then and there a fatal lack of empathy with those to whom democratic rights matters a great deal, as it always does to those who are violently deprived of them by authoritarian regimes of the left as well as right.

He does not bring out perhaps quite sufficiently here the connection between a basic commitment to democratic values and the struggle against antisemitism. This appears to be a conscious decision but one which is taken at two levels, as it were. At one level, this is because this is, deliberately, a personal memoir and not a political text of any kind. Readers who want to know more about his political writings are advised to go to them directly, as he does not summarise them here to any great extent. This seems a pity, as many readers would surely gain a lot from even a short summary and might be more inclined to go and read them, if they have not already. But, at another level, and specifically on the question of antisemitism, he made at some point a clear decision no longer to engage, at least with regard to Germany, with what he calls ‘the thing’, that is, ‘a noxious and indeterminate but clearly discernable amalgam of antisemitism, anti-Americanism, German nationalism, Nazism and anti-Westernism, to name only its main ingredients.’ As he rightly notes, in all of this ‘Jews were in some fashion at its core’, and of course they still are.[1]

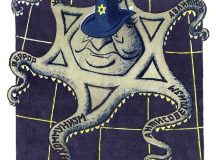

It is a shame, in particular, that he does not explain here more fully quite why Jews are so central to this amalgam, or summarise here his important argument that contemporary antisemitism is intimately bound up with anti-Americanism. In a number of works,[2] he has argued compellingly that what connects them is (amongst others) the sense that they are both badges of honour and generally acceptable among those who like to think of themselves as progressive; that they have been widespread among cultural elites and intellectuals for a long time, gained in strength with the collapse of communism and have been especially resurgent in the 21st century; and that they both draw, wittingly or unwittingly, on several Nazi claims. What the Nazis said especially about the United States as being dominated by Jews is now rearticulated in the claim that Israel is a tool of the United States or (even worse) vice versa. Of course, this argument also had its Soviet version, with which the memoir begins, in the claim that Jews were not only rootless cosmopolitans but also Zionists. Despite the obvious contradiction between these two assertions (since cosmopolitans are, by definition, not nationalists and Zionism is a form of nationalism, even apparently the very worst), what connects them is the antisemitic belief that Jews are fundamentally disloyal, alien, not to be trusted, and engaged in a global conspiracy to thwart the forces of progress.

One feels considerable sympathy for the author’s justification for withdrawing from debates with those who promulgate this rubbish on the grounds that they are ‘never ending’, as they are indeed. But he also provides, at least implicitly, some interesting observations as to how and why this toxic amalgam has such an appeal, and at what level this appeal operates. As well as his work on anti-Americanism and antisemitism, he is probably even better known for his work on West German politics and society, on trade unions and on both Red and Green parties. In the process, he developed a strong sympathy for a polity which has developed some sturdy and quite resilient liberal democratic institutions for the first time in German history, and notes that those who, in the Federal Republic, have taken a commitment to liberal democratic norms and values most seriously are also those have shown the most compassion for and interest in Jews. But he also notes[3] that this compassion and interest has largely been lacking (and one might add is even more lacking today[4]) on the radical anti-fascist left. But at the same time, he observes that even the compassion and interest of the former may not have such deep roots, because there is another realm, that of the emotions, below the surface, where things may not be so straightforward. What this observation may be connected to is a crucial argument made some time ago by Sartre[5], that one cannot reason with antisemites. Their ‘arguments’ cannot be countered with logic or evidence because antisemitism is a passion. Antisemitism is not about what Jews do or do not do; it is about what antisemites fantasise about and what they project on to Jews. That is an important part of what makes arguing against antisemites so upsetting and dispiriting. There is, all too often, no argument in principle, no evidence one can point to that would make them change their minds.

Perhaps the best that one may hope for sometimes is the richness of a life lived without such a destructive set of emotions, the worth of work that is grounded on logic and evidence, the support of people (as the author generously attests to in this memoir) from whom one can learn and with whom one can share insight and understanding. It is this record and these experiences, perhaps above all, which shine brightest out of this evocative memoir.

References

[1] Se the brief discussion on p.276.

[2] See in particular his Uncouth Nation: Why Europe Dislikes America, Princeton University Press, 2007; and the brilliant essay in ‘European Anti-Americanism (and Anti-Semitism): Ever Present Though Always Denied’, Center for European Studies Working Paper Series #108, http://aei.pitt.edu/9130/1/Markovits.pdf, accessed 24/11/2008.

[3] See the brief comments on this on p.295 where he notes that ‘some of those who disdained the Bundesrepublik later drifted right, some becoming outright German nationalists, even Nazis’. What was common to the original anti-fascism and the later turn to fascism by some was antisemitism. This is not that surprising since the original anti-fascism of the New Left generally failed to recognise the specificity and depth of antisemitism. Much the same could be said of today’s anti-imperialist left. For a valuable account of some of the different trajectories of some in the German New Left, in which the question of how to think about and respond to antisemitism is central, see Hans Kundnani, Utopia or Auschwitz: Germany’s 1968 Generation and the Holocaust, New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

[4] Those who can stomach it could look, for example, at the so-called ‘catechism debate’ that has been taking place in Germany today, where it has absurdly been claimed that the memory of the Holocaust there (of all places) is being used for racist purposes to block recognition of other injustices committed by the West (the only crimes apparently of any interest to many). A whole set of antisemitic tropes are reappearing in this context. For a (quite mild and restrained) rejoinder to this disturbing development, see the piece by the great Holocaust historian, Saul Friedländer, ‘The Holocaust as a fundamental crime’ which may be found here: https://k-larevue.com/en/saul-friedlander-a-fundamental-crime/.

[5] In his Anti-Semite and Jew: An Exploration of the Etiology of Hate, New York: Schocken, 1995. It was first published in 1946 but is still highly relevant today.