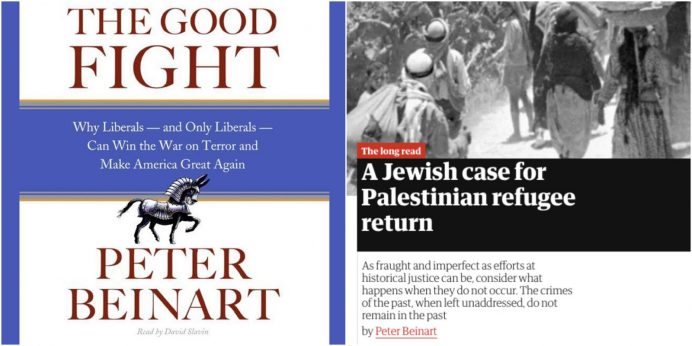

Peter Beinart backed the US invasion of Iraq. He called it ‘the Good Fight’ and wrote a 2006 book about how the war would ‘Make America Great Again’, end the ‘war on terror’ and bring democracy to the Middle East. In 2021, in his essay ‘Teshuva: A Jewish Case for Palestinian Refugee Return,’ he has proposed another massive experiment in social engineering and state building in the Middle East. Joshua Brook, an attorney and former aide to the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, argues that while Beinart has travelled far politically since 2006 he has learned little: he is still focused on moral simplicities while ignoring political complexities. He conflates Palestinian moral claims with legal rights, Palestinian historical memory with possible political solutions and the result is a simplistic, unworkable and dangerous proposal that does not advance Palestinian statehood one inch.

There is a point beyond which even justice becomes unjust. — Sophocles

In ‘Teshuva: A Jewish Case for Palestinian Refugee Return,’ (Jewish Currents) Peter Beinart uses the liturgy of Jewish historical memory to plead for empathy for displaced and dispossessed Palestinians and their descendants. His call is most welcome, for only by respecting the others’ historical narrative, acknowledging their pain, and taking responsibility for past and present wrongs can we begin to heal this century-old conflict. But by conflating historical memory, legal rights, moral claims, and political resolutions, Beinart’s essay obfuscates more than it illuminates. Respecting another people’s national memory should indeed evoke empathy, but it does not require wholesale adoption of their self-justifying narrative of blamelessness, nor accession to their maximalist political demands, particularly where those demands include national suicide. And Beinart’s implicit claim that only one party to this tragic conflict is due an historical reckoning is as unlikely to further the cause of peace and reconciliation as it is morally obtuse.

Beinart treats four distinct concepts — historical memory, legal rights, moral claims, political resolutions — as essentially one and the same, thereby creating a miasma of confusion and non-sequiturs. He reasons that since the Arabs of Palestine suffered a genuine human and societal catastrophe in 1947-48 (true) and because they are entitled to memorialise those events in a national narrative (also true), that therefore they have a moral and historical claim to ‘return’ (plausible) which equates to a legal right (false) to be able to settle seven million Palestinian ‘refugees’ inside Israel (also false). For the sake of clarity, I shall attempt to untangle these distinct concepts in a way which, I hope, respects the Palestinian narrative without erasing the Jewish one, and which points the way toward a more likely political resolution than the dangerous, extreme, and unworkable position advocated by Beinart.

Part 1: Beinart Confuses Legal Rights and Moral Claims

Beinart believes that since Palestinians feel a historical attachment to the land they lost in 1948, that they therefore have a moral claim to ‘return’ to those lands and reclaim their lost property, and that this moral claim is enshrined as a right in international law. But the conclusion does not flow from the premises.

Morality is absolute and also highly subjective, but a legal system must balance conflicting interests and provide objective rules to govern conduct, the application of which may result in substantive injustices, but which are a necessary consequence of a rules-based system. Most, if not all, legal systems distinguish between moral claims and legal rights, and provide a variety of remedies where rights are violated. For example, restitution for even the most outrageously immoral conduct may be barred by a statute of limitations, in both criminal and civil contexts. And under the Fifth Amendment to the US Constitution, a person cannot be compelled to give testimony against himself, even if withholding it leads to injustice. With this in mind, we can distinguish between the moral and historical claims of Palestinians and their legal rights.

There is no Palestinian right of return in international law. None of the legal (as opposed to moral or historical) claims made by Palestinians and echoed by Beinart are remotely persuasive as legal claims, as they are based on non-binding General Assembly resolutions, the retroactive application of human rights treaties, and state practices which developed almost a half-century after the Palestinian Nakba.

This is not a grey area or a close call. The definitive case was laid out by Andrew Kent in the University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law.[1] Importantly, Kent’s article assumes, for purposes of argument, that Israel bears 100 per cent of the moral responsibility for the creation of the refugee problem:

I have assumed the truth of the Palestinian claim that Israel is entirely to blame, in order to sharpen the analysis of the applicable international law. In this posture, it becomes clear that the claimed Palestinian ‘right of return’ for refugees from the 1947-49 conflict has no substantial legal basis (emphasis added). While the aspirations of the displaced to return to their homeland are understandable and compelling, the data compiled for this Article show that tens of millions of people were expelled from their countries during the twentieth century before international law began to recognize that practice as always illegal, and before international law began to require that refugees be able to return home in some circumstances … Though it is no doubt deeply unsatisfying to Palestinians and their many supporters, the correct legal answer to the question of whether the 1947-49 refugees have a right of return under international law goes something like this: even if (or assuming that) the Israelis did intentionally expel every Palestinian refugee, it was not illegal when it occurred, though it almost certainly would be if done today under the same circumstances; and the law at the time did not require repatriation of the refugees to Israel, though it most likely would if the expulsion were to occur today.[2]

Beinart (who is not a lawyer) correctly acknowledges the flimsiness of the legal arguments in favor of a ‘right of return’ but then blithely dismisses international law itself, writing: ‘But these are legalisms devoid of moral content.’ — as if the validity of the international legal system depends on whether or not it measures up to the moral sensibilities of Peter Beinart.

This is not mere semantics. The mischaracterisation of the Palestinian demand for ‘return’ as a legal right, rather than an (understandable) longing or political demand, has done severe harm to Palestinians, Israelis and the entire world by unnecessarily perpetuating for seven and a half decades a conflict which could otherwise have been solved by a simple real estate transaction.

The Palestinians’ mistaken belief (tragically indulged by Western intellectuals, Arab states, and the United Nations) that they have a legal right to settle within Israel’s 1949 borders renders any compromise on this point, not merely an unpleasant consequence of military defeat, but rather a betrayal of a people’s fundamental rights and dignity. For while dreams can be deferred, and demands negotiated, rights (as Thomas Jefferson reminds us) are inalienable. That no Palestinian leader would ever acquiesce in such treachery explains why the Palestinians have rejected numerous offers of statehood, self-determination, and independence, and why they remain stateless to this day.

Of course, Palestinians can make a moral and historical claim that they are the rightful sovereigns over Jaffa, Haifa, Akko and all of the lands of 1948. So too can Mexicans articulate a claim that they are the rightful sovereigns over California, Greeks over Istanbul, Iraqis over Kuwait, Serbs over Kosovo, Swedes over Norway, Jews over Hebron, Jericho and the Temple Mount, and Germans over Alsace-Lorraine and half of Poland. But the international legal system does not — cannot — give any legal force to such claims because doing so would unleash global anarchy. After all, peoples migrate, they are conquered, expelled and colonised, while empires rise and disintegrate. Any given piece of territory may have multiple peoples who can articulate historical and cultural connection to it, and all of their mutually exclusive claims cannot be simultaneously validated. This is true for almost all the Earth’s territory, but not least the Southern Levant which has been continuously inhabited by human civilisations for over 5,000 years.

What the international legal system does recognise is states, which can be composed of multiple peoples or nations but which more typically have one dominant, majority ethnicity and smaller minority populations. States have sovereignty over their territory and sole authority over immigration to it.

It is an accepted maxim of international law, that every sovereign nation has the power, as inherent in sovereignty, and essential to self-preservation, to forbid the entrance of foreigners within its dominions, or to admit them only in such cases and upon such conditions as it may see fit to prescribe.[3]

Most states have accepted voluntary limitations on this sovereign power by adopting the Refugee Convention, and some states have generously chosen to extend citizenship and/or compensation to the descendents of refugees. Beinart notes that some European countries have offered citizenship to the descendants of Jewish refugees, but mistakenly concludes that this favors a ‘right of return.’ As sovereign states, these countries have plenary power over immigration and may offer citizenship to whomever they so choose. That they have chosen to do so for the descendants of Jewish refugees is commendable. But it is just that — a voluntary choice by sovereign states.

And while Austria and Spain have laudably made such offers, most states have not. My own grandfather was a refugee from what is now Ukraine, where my family lived for hundreds of years before being driven out and having their property seized by antisemites who were tolerated and encouraged by local authorities. Despite these historical injustices, Ukraine has not offered citizenship, compensation or repatriation to me or my 15 cousins and siblings. Does Beinart really believe that Ukraine is violating our human rights?

In no legal system of which I am aware is the right to property absolute — even for those in current possession, let alone for their great grandchildren. When we enumerate what are generally thought of as human rights (right to life, liberty, property, due process of law, freedom of religion and conscience, freedom of expression etc.) the right to live in the exact same spot as one’s great-grandmother is typically not among them, for obvious reasons.

I have legal title to my apartment in New Jersey. I also believe I have a strong moral claim to it, though I recognise that it sits on the historic homeland of the Lenape people who were likely dispossessed under dubious circumstances. Nevertheless, my apartment can be seized at any time by the state of New Jersey, provided I am paid its equivalent value in cash. That is, I have no absolute right to my own home, merely a right to compensation if it is confiscated by the state. Do the great grandchildren of refugees displaced in the chaos of war enjoy a greater right to property which they have never owned, in a country in which they have never lived, than a citizen of a democracy has over his own home in which he currently lives? The absurdity of such a proposition should be obvious to all.

Part 2: Beinart Confuses Historical Memories and Political Solutions

Beinart is at his strongest when he recounts the genuine suffering of Palestinians during the Nakba and the injustices and even atrocities inflicted on them by the Zionist forces. And he is certainly correct that the Jewish people’s own long and tragic history of persecution and displacement should inspire empathy for Palestinians. But instead of grappling with moral complexities and dilemmas, Beinart has merely exchanged one simplistic, one-sided narrative for another. For while the history of the Nakba and especially its causes remains contested, no one can seriously deny that expulsions and massacres of civilians were committed by both sides.

Jews and Israelis absolutely must reckon with the injustices and atrocities perpetrated by the Zionists in 1948, in which 70 per cent of the Arab population was uprooted. So too must Arabs and Palestinians acknowledge the atrocities committed by their forces in displacing 100 per cent of the Jewish population of the part of Palestine under their control, and 99 per cent of the Jews of the Arab world in the years that followed. (Historians continue to debate whether this horrendous human suffering was an inevitable consequence of Jewish self-determination, or rather of a war of choice waged by Arabs to prevent dhimmi sovereignty over any part of a formerly Islamic empire.)

But perhaps Beinart’s most serious error is his conflation of the right to historical memory with political resolution. For just as genuine historical trauma and memory does not equate to a legal ‘right of return,’ neither does the denial of such a purported ‘right’ require the erasure of historical memory.

Beinart laments the

bitter irony of Jews telling another people to give up on their homeland and assimilate in foreign lands. We, of all people, should understand how insulting that demand is. Jewish leaders keep insisting that, to achieve peace, Palestinians must forget the Nakba, the catastrophe they endured in 1948.

But this makes no sense. Recognising Israeli sovereignty over its 1949 territory does not require Palestinians to ‘forget’ the Nakba, any more than acknowledging American sovereignty over San Francisco requires Mexicans to forget the injustice of 1848 or recognising Turkish sovereignty over Istanbul requires Greeks to forget the thousand-year history of Constantinople, or their brutal conquest and expulsion by the Muslim Sultan Mehmet the Second in 1453.

Palestinians will continue to mourn the Nakba as part of their national identity, regardless of what political arrangements are ultimately entered into with Israel. That is their right, and it must be honored and respected. But as long as Palestinians (aided and abetted by Western intellectuals like Beinart) falsely equate memory with the realisation of unattainable, maximalist political goals (i.e. destruction of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people), they will ironically prolong the statelessness and destitution of the Palestinian people by refusing any compromise which would allow them to move forward. This has been the tragic history of the conflict thus far, with Palestinians rejecting multiple offers of statehood and independence.

Over the last year, many countries have begun a process of national introspection and reckoning with historic injustices. Some are also considering ways to make restitution to the descendants of those who were mistreated. This process is welcome, difficult though it may be. However, the form of such restitution must reflect current realities and not create more suffering and bloodshed. Historical injustices should be acknowledged and accounted for, but this does not render every proposed reckoning practical, right, or just. As the ancient Greek tragedian Sophocles reminds us: there is a point at which even justice becomes unjust.

Should Algerian Arabs acknowledge that their conquest and colonisation of (what is today) Algeria in the Seventh Century dispossessed and marginalised the indigenous Berber population? Perhaps they should. But if Berber activists were to demand that this historic injustice be remedied by the forced repatriation of millions of Algerian Arabs to Arabia, what would ensue would not be justice, but civil war.

Jews will forever mourn the destruction of the Temple by the Roman legions in 70 CE. Are we therefore entitled to reparations from the Republic of Italy (as successor state to the Roman Empire) for all of the wealth that was looted, along with 1,951 years of compound interest? Or should this historic injustice be rectified by the reconstruction of the Temple on the site of its predecessor, along with demolition of the structures built by Arab imperialists in the Seventh Century? Perhaps — along Beinartian lines — the Third Temple could be built between al-Aqsa and the Dome of the Rock so the plaza can be place of religious ‘equality.’ Are Muslims who oppose this insane proposal (and I’m guessing it’s all 1.8 billion of them) thereby enemies of ‘equality’ or proponents of religious ‘apartheid’? Is their refusal to acquiesce in such a harebrained scheme equivalent to asking Jews to forget our history?

Obviously, it is easier to rectify injustices which occurred in recent decades than those of distant centuries. But this only illustrates the larger point: that historical restitutions are not absolute, but contingent on the practicalities of current circumstances and the legitimate interests of all parties involved. One lesson we all should have learned from the Twentieth Century, but which seems lost on Peter Beinart, is that utopian political programmes that promise absolute ‘justice’ always end in rivers of blood.

What Beinart proposes is that Israel settle within its sovereign territory millions of people who for generations have been taught that Israelis are evil incarnate, who believe they have billions of dollars in outstanding property claims against them, and whose religion teaches that the proper role of Jews is as their social and political inferiors. What could possibly go wrong?

Nevertheless, despite their 100+ years of bloody conflict, Beinart assures us that Israelis and Palestinians would live peacefully together in a post-Israel unitary state. And he does so with the same confidence with which he prophesised Shia-Sunni harmony in post-Saddam Iraq.[4] If his catastrophic lack of foresight then has inspired any humility, it is not evident from his writing, for now he is again proposing a massive experiment in social engineering and state-building in the Middle East. Last month, the potential ‘return’ of a handful of families to their pre-1948 property in Sheikh Jarrah triggered a war that claimed hundreds of lives. Beinart proposes to replicate this experiment by the millions.

Beinart assures us that many of his Palestinian colleagues believe deeply that Jews would be safe under a one-state arrangement in which they would be at the mercy of the Palestinians. I have no reason to doubt their sincerity. But I do question their judgment. Has it not occurred to Beinart that his new Palestinian friends may be no more representative of their society than the well-intentioned Iraqi exiles who counseled him in favor of invasion?[5]

When in the midst of the recent wave of horrific antisemitic attacks perpetrated by Palestinians and their supporters worldwide, Beinart tweeted: ‘I don’t know the [expletive] who in the name of Palestinian freedom are attacking Jews across the world. I hope they spend time in jail. But every Palestinian I know believes that Palestinian freedom + Jewish safety not only can coexist but must. That gives me hope,’ I was reminded of his fellow New York intellectual who, after the 1980 presidential election wrote words to the effect of: ‘I can’t understand how Ronald Reagan won. Not a single one of my friends on the Upper West Side of Manhattan voted for him.’

But if the massive resettlement of millions of Palestinians inside Israel should be rejected because it risks civil war, does not Israel still have a moral obligation to make right some of the wrongs committed in its past? It does, and it should. But the implementation of this moral obligation need not entail national suicide.

Israel has, in fact, shown a willingness to make amends for injustices visited on Palestinians. In the 2001 Clinton Parameters, Israel agreed to acknowledge the ‘moral and material suffering caused to the Palestinian people by the 1948 war, and the need to assist the international community in addressing the problem.’ And in 2008, Prime Minister Ehud Olmert offered the resettlement of 150,000 Palestinians inside Israel. Most importantly, under every peace plan agreed to by Israel, Palestinian ‘refugees’ would have an unlimited right to return to the state of Palestine, and to exercise self-determination in their historic homeland. They would also be financially compensated for property which was abandoned and subsequently confiscated.

Of course, return to Palestine is not really what the ‘right of return’ means. When Palestinians claim a ‘right of return’ they mean, not a return to Palestine, per se, but rather a return to the exact spot (in some cases the exact houses!) in Palestine in which their ancestors once lived. It is thus a species of nationalist maximalism (Greater Palestine), not unlike that of the most fanatical Jewish West Bank settlers whom Beinart rightly deplores. Of course, Palestinians are entitled to press their maximalist claims (though I believe they are unwise to do so) but nationalist extremism should not be aided and abetted by confused Western progressives mouthing the language of human rights. Greater Palestine is no more progressive than Greater Israel, Greater Hungary, Greater Iraq, or Greater Serbia.

Part 3: Two Households, Both alike in Dignity

Palestinians and their supporters have lately taken to describing Zionism as a form of ‘settler colonialism’, a type of colonisation in which settlers disposess and replace the indigenous population (e.g. North America, Australia, New Zealand, etc.). Palestinians characterise Zionism as colonialism for obvious reasons. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews in large numbers began to settle on land which had been an ancient Jewish kingdom, but in which Arabs had constituted a majority for centuries. From the Arab perspective, people whom they perceived as foreign came to their land from (mostly) Europe, speaking strange languages, wearing different clothing, and began buying land in an effort to radically transform the country and reduce the status of Arabs to a minority. To those on the receiving end, this feels a lot like colonialism, and Palestinians are certainly within their rights to describe it as such.[6]

Nevertheless, the essence of Zionism is, paradoxically, anti-colonial: the restoration of an indigenous people to its historic homeland. Israel is the place from which the Jewish people (i.e. the Judeans) began: the origin point of Jewish religion, culture, language, and sacred texts, and the locus of holy places and the direction of prayer. Indeed, the Jewish people are the only nation that has ever been sovereign over that land, both in antiquity and post-1948. All others who lived there did so, not as sovereign nations but as subjects of various empires. One could even make the case that Zionism is the most radical anti-colonial movement in human history, undoing as it did, not only the effects of Western colonialism but also Turkish, Mamluk, Arab, Byzantine, Roman, Selucid, Ptolemaic, Greek, Persian, Babylonian, and Assyrian colonialism, and thereby returning territory to its original indigenous nation.

That Zionism is both a colonial and anti-colonial movement at the same time is part of the complexity of the conflict. Conceptualising Zionism as both colonial and anti-colonial is historically correct and also a useful paradigm allowing both Israelis and Palestinians to remain faithful to their respective narratives without denigrating the others legitimacy.

One is reminded of the famous image of an animal’s head that resembles both a rabbit and a duck, depending on how you look at it. Some see a rabbit; others, a duck. In his wholesale and uncritical adoption of the Palestinian narrative and concomitant rejection of the Jewish one, Beinart resembles nothing so much as a man who, staring at the image, declares: ‘Eureka! For years I believed that this was a rabbit. But now I see so clearly — It’s actually a duck! And anyone who can’t see that, is guilty of anti-duckian bigotry.’ While many in our Jewish community proclaim with equally earnest indignation — ‘This is a rabbit, and if you claim it’s a duck then you are an anti-rabbite!’

But rather than hurl such pointless accusations, both sides must make room in their moral imaginations to recognise the other’s perspective as legitimate, even if they do not share it. ‘To me, it looks like a rabbit but, given your experience and the history of your people, I can understand why it looks like a duck to you.’ And vice versa. To be sure, the scale of injustice suffered by the respective sides is not equal because the Zionists won and the Palestinians lost. Israel is strong and the Palestinians are weak. Israel is occupier and Palestinians are occupied. But in the legitimacy of their respective claims, and in their historic and cultural attachment to the land, Jews and Palestinians are ‘two households, both alike in dignity.’

Conclusion: ‘And Japheth shall dwell in the tents of Shem’[7]

Monotheisms like Judaism and Islam are prophetic and therefore moralising. Moralism has its place, of course. But perhaps in this instance we can both learn from our cousins across the Mediterranean, the ancient Greeks who, as the late Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks reminded us ‘gave the world the concept of tragedy.’ In the wisdom of ancient Greece we discern that human suffering results not solely because some are good and others are wicked (though some certainly are) but rather because all are flawed, broken, and capable of seeing only partial truths.

Both Israelis and Palestinians need to acknowledge the humanity, suffering and dignity of the other — and, perhaps even more importantly, the other’s legitimate history in and connection to the land they share. In that sense, Peter Beinart’s call for Jews and Israelis to acknowledge the Nakba is correct and welcome. But the events of 1947-48 and since are considerably more morally ambiguous than either Beinart or the standard Palestinian narrative acknowledges, and Beinart’s suggestion that all that peace requires is Jewish self-flagellation and the unlimited settlement of some seven million Palestinians inside Israel is as shockingly naive as it is dangerous. Requiring only one side to a bitter conflict to perform heshbon ha-nefesh while the other side clings stubbornly to its most cherished myths of blamelessness and purity, no matter how morally simplistic or historically unjustified, is not a recipe for social peace, regardless of what political settlement is ultimately agreed to.

Peter Beinart’s essay is titled ‘Teshuva’ a reference to the Jewish rite of atonement practiced most prominently around the high holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. The metaphor is apt, and the process painful, but necessary. Yet Beinart would do well to recall this passage from the Machzor: ‘Who among us is righteous enough to say: ‘I have not sinned’? For verily, we have all sinned.’

References

[1] https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1498&context=faculty_scholarship

[2] Though the practice of ethnic cleansing is probably as old as warfare itself, the term ‘ethnic cleansing’ dates only to the Balkan wars of the 1990s. See https://www.refworld.org/docid/582060704.html. In the 1940s, not only was population transfer not considered illegal under international law, it was actually endorsed by the United Nations at the Potsdam conference. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potsdam_Agreement. The first international treaty banning mass expulsions was promulgated by the Council of Europe in 1963. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flight_and_expulsion_of_Germans_(1944–1950)#Status_in_international_law.

[3] Nishimura Ekiu v. United States, 142 U.S. 651, 659 (1892), cited as good law by the US Supreme Court as recently as last year, in DHS v. Thurraissigiam, 140 S. Ct. 1959 (2020). See https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/19-161_g314.pdf

[4] See also his 2006 book The Good Fight: Why Liberals – and Only Liberals – Can Win the War on Terror and Make America Great Again.

[5] In particular, Beinart has cited Kanan Makiya as an influential Iraqi exile who persuaded him to support the invasion. Beinart later wrote. ‘Made desperate by Saddam’s horrors and his resilience, [Makiya] was willing to gamble. I was willing to gamble too—partly, I suppose, because . . . I wasn’t gambling with my own life.’

[6] https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781627798556

[7] Genesis 9:27.

It is important to remember that the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine, under the leadership of the Zionist movement, accepted the UN partition plan in 1947. That means that the Zionist accepted the fact that two peoples live in Palestine and both have the right

to independence. But the Arabs not only rejected the partition but also started a war against the Jewish community aiming to prevent by force the implementation of the partition. Against all odds the Jews won the war and Israel was founded. The majority of the refugees left because of the flail of war. They were sure that they will be back very soon after the certain victory of the Arabs. Some were expelled, like in Ramle, but that too was due to the war they started.

The responsibility for the Nakba lays on the shoulders of the Arabs themselves. If they did not start the war there would have been no refugees, the lives of thousands, on both sides, would have been spared and their state would have been 73 y old today.

I leave to Beinart’s imagination to guess what would have been the fate of the Jewish community if the Arabs had won the war.

Has Beinart ever been right on anything?

The article is really interesting but I find it unfortunate that it is so ambiguous. Indeed, even if the Palestinian narrative were correct, it would not have the implications (from a legal or moral point of view) that the Palestinians claim. But it’s a shame that this article simply forgets to point out that the Palestinian narrative is false. The vast majority of Palestinians have voluntarily left their homes because of the appeal of the Arab countries who told them to leave while they destroy Israel. Except that Israel won. If there have been cases of ethnic cleansing against Palestinians: they have been exceptional cases.

And as unfortunate as it is these events, when you look at the context (that of the war), it is hardly surprising that there have been a few cases of ethnic cleansing. In fact, what is astonishing is that the Jews were so moderate. (Yes because when we compare to other conflicts of the time, the Jews showed great moderation).

I have no problem acknowledging the suffering of the Palestinians, but the problem is that the Palestinian narrative is a lie. They want at all costs to present themselves as victims of the wicked Zionists. Result: they created an alternative history. Palestinians should start by stopping distorting history.

Besides, a funny thing, if the Palestinian narrative were true, there wouldn’t be 20% Arab Israelis today. Indeed, how to explain that the Israelis did not fire all the Arabs if they had committed an ethnic cleansing which aimed to remove all the Arabs (this is what the Palestinians claim) ???

Arab leaders are largely responsible for the suffering of the Palestinians. They were the ones who told them to leave. It was the Arab leaders who decided to put the Palestinians in separate camps by forbidding the Palestinians to acquire the nationality of the countries in which they live. But this is also true for their descendants. (The only exception is Jordan). Israel cannot be held responsible for things that have been done by Arab countries.

The right of return was invented for the purpose of destroying Israel.

1) Peter Beinart also said that it is unfair for Jews who prayed for 2,000 years to return to their ancient homeland, to expect the Palestinians to give up on the idea of returning to their land. This claim is misleading. The whole idea of a 2-state solution is that Jews and Palestinians must exercise their right of return in part of the land only.

2) What’s more, there is a way to reconcile the two-state solution with the right of return: a confederation with open borders and freedom of movement for both peoples throughout Israel/Palestine.

3) Finally, Peter Beinart seems to believe that it was unfair for Jews to establish their state in a land already inhabited by other people. Gideon Shimoni wrote a very interesting article explaining how Israel’s founding fathers addressed this moral dilemma: they claimed that leaving the Jews homeless would be a greater injustice than depriving the Arabs of part of their land. Thus, the Arabs who had enough land must share with the Jews who had nothing.

One can oppose this rationale, but it is neither “racist” nor “colonialist”. It is based on the principle of distributive justice (redistribution of wealth), which is the hallmark of left-wing politics. Strangely enough, when Jews too demand a piece of the pie, they are called thieves!

https://www.academia.edu/38091044/The_Discourse_on_Right_to_the_Land_of_Israel_in_Zionism_and_Israel