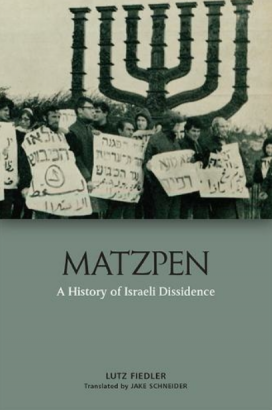

Lutz Fiedler’s highly informative book about the far Left group, Matzpen, is a welcome addition to the recording of both Jewish and Israeli history. This book started life as a doctoral thesis under the supervision of Professor Dani Diner, a stalwart of the international Jewish Left in the 1970s. The original German version has now been published in English by the University of Edinburgh.

For many in the Israel advocacy arena, the very mention of Matzpen is anathema, yet Fiedler’s overview provides insights into its place in the flow of Jewish history.

It provides an entry point as to why Matzpen came into existence, why it has lasted and why it is more than an excursion into an ideological la-la land. It is also a history of schisms and coalescences — as befits the international far Left, attempting to locate the valhalla of theoretical perfection.

Matzpen thus begat Hazit Aduma (Red Front) which led Udi Adiv from Kibbutz Gan Shmuel in 1972 to a training camp near Damascus and being cultivated by Syrian intelligence. He was arrested after his second visit and sentenced to 17 years.

Intolerance and intransigence as well as principle colour Matzpen’s odyssey. Its leaders bear a resemblance to the Rebbe in his hasidic court, surrounded by devoted followers.

At the end of September 1962, the Israeli Communist Party (CPI) expelled four of its younger members, Moshe Machover, Akiva Orr, Haim Hanegbi and Oded Pilavsky. They had been in an ideological and generational tussle with the party elders for some time. They were accused of constituting ‘an anti-party group’, agitating against the Soviet Union and criticising Communism itself. This ‘gang of four’ became the nucleus of Matzpen, the Israeli Socialist Organisation which positioned itself on the peripheral anti-Zionist Left in Israel, but was enthusiastically embraced by the European New Left in the late 1960s.

All had been born in the 1930s — and had come of age during the halcyon days of socialist Zionism and the building of the state. The bright uplands of the socialist future, led by the Marxist-Zionist Mapam and the CPI began to dim considerably during the last years of Stalin. The killing of Solomon Mikhoels, the head of the Yiddish theatre, the execution of Jewish poets and writers in August 1952, the Slansky trial of leading Czechoslovak Communist leaders — mainly Jewish, the Doctors Plot of January 1953 — all marked Stalin’s open anti-Semitism.

For the pro-Soviet Mapam, it was the arrest, trial and incarceration of one of their emissaries, Mordechai Oren, on a fraternal visit to Prague that created turmoil. Many struggled with their consciences — how could a true believer such as Oren be an agent of imperialism? The marriage between socialist internationalism and Zionist particularism was in trouble.

Mapam, a grand coalition of the Zionist Left, fragmented. One faction resurrected Ahdut HaAvodah, but a small group of the pro-Soviet faithful, led by Moshe Sneh, a former General Zionist and commander of the Haganah, left to form a splinter party, Siat Smol, (the Left Faction). In a further move in November 1954, Sneh led his followers into the Communist Party. They included Machover, Orr and Pilavsky. They were blinded by their ideological disdain for Zionist politics in Israel to the extent that they could bypass the growing evidence of Stalin’s crimes and the parallel universe of the Gulag.

Machover had been expelled from the Left wing Zionist movement, Hashomer Hatzair, but his political awakening and resurrection from the Stalinist dead, came about during a year-long sojourn in Poland. He met dissidents such as Jacek Kurón and the famed leader of the Red Orchestra spy ring during World War II, Leopold Trepper. He discovered the reality of the Soviet paradise, moulded in Stalin’s image.

At the same time, he was also perplexed that the Communists did not take power in Baghdad in 1958 after the overthrow of the Iraqi monarchy. Why had Moscow allowed the Baathists and the Nasserists to take power? History records that the Iraqi Communists were liquidated in the years to come.

Meir Vilner, the secretary-general of the CPI, too had left Hashomer Hatzair and joined the Communist Party in Poland. In Israel, he had proudly signed the Declaration of Independence during the Soviet Union’s brief pro-Israel period. He had also attended the Twentieth Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union when Krushchev revealed Stalin’s crimes — and said not a word on his return to Israel.

The growing dissatisfaction with the CPI leaders led to expulsions of members when they had asked difficult questions about the Slansky trial, the Night of the Murdered Poets, the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 and the simmering disquiet about the fate of Soviet Jewry.

There was also the singular frustration of the younger generation who were critical of the official version of the establishment of the state. In one sense, they preceded the New Historians by thirty years, but they also did not understand the complexity of the exodus of the Palestinian Arabs — revealed later by academics such as Benny Morris after the opening of the archives.

Some moved to the right. Others joined Mapai or returned to Mapam. Still others went to the post-Soviet far Left — they argued that the dream was real, it was just the people, conjuring up the dream who were at fault. All these emotions poured into the establishment of Matzpen in November 1962. The first edition of their magazine bore the headline, ‘There is an Address’.

Matpen’s political agenda was to deZionise Israel and integrate it into a socialist Middle East. They would reinvent ‘Israel’ as an emergent Hebrew nation.

In Israel, they grew distant from Moshe Sneh who followed a Eurocommunist, proto-Zionist path after the split in the CPI in 1965. It signified a distance between the Old Left and the succeeding New Left of the 1960s. Lutz Fiedler comments: ‘What divided them was not their politics or agendas so much as a near-unbridgeable gulf between an optimistic faith in progress and lived experiences of a miserable century.’

Figures such as Leopold Trepper and Yosef Berger-Barzilai, ‘the shipwreck of a generation’, who had sacrificed years of their lives in striving for a socialist future became inconvenient reminders of a less than perfect past.

Matzpen found its salvation instead in the Cuban Revolution and FLN’s struggle in Algeria. The writings of Franz Fanon were influential together with the new Algeria of Ben-Bella. The army coup of General Houari Boumédiènne in June 1965 changed Algeria’s course to one of Arab nationalism. Jewish Marxists were forced to leave and Boumédiènne told them that ‘your country is Israel, not Algeria’.

Machover and Orr came to London and found a welcome reception from the International Marxist Group and the International Socialists and from periodicals such as Black Dwarf and Red Mole. All this took place during a period of decolonisation in the UK when the saga of the Palestinians fitted in much more easily than the cause of the Israelis — and this was before the Six Day War and the settlement drive on the West Bank.

Matzpen entered into a dialogue with the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) of Nawef Hawatmeh in the late 1960s, but this was wrecked by the attack of the DFLP on Ma’alot in 1974 in which 25 Israeli civilians were killed. Following the Palestinian National Council in June 1974, when the possibility of a two-state solution was first mooted, the PLO began to search for Israelis to talk to, at first anti- and non-Zionist groups including Matzpen and concluding with Yitzhak Rabin in the 1990s. Moshe Machover therefore met the PLO’s man in London, Said Hammami, during the 1970s before his assassination by the Abu Nidal group. Members of Matzpen later published the periodical, Khamsin with Arab intellectuals.

Matzpen also leafleted demonstrations for Soviet Jewry in London at the end of the 1960s. Were they attempting to persuade Soviet Jews not to go to Israel? Or should they leave the USSR with a non-Zionist mindset in order to join the Israeli struggle for socialism?

Matzpen members were clearly unable to understand Diaspora Jews. There is a telling passage in this book about the reaction of Akiva Orr, born Karl Sebastian Sonnenberg in Berlin in 1931, to the fears of an old Golders Green Jew on the eve of the Six Day War: ‘Will they destroy us?’ asked the old man. ‘Who is ‘us’?’ asked Akiva Orr.

Matzpen collected its members from long time Trotskyists in Palestine, members of Heinrich Brandler’s Right Communist opposition to the official party in Germany, Arab Marxists and displaced German Jews who could only find sanctuary in the Palestine of the 1930s. The author quotes Jakob Taut that he and his comrades at that time fought three enemies — the Zionists, the imperialists and the Stalinists. Why then were the Nazis missing?

This mirrored the journey of Yigael Gluckstein aka Tony Cliff, founder of the Socialist Workers Party in the UK. Gluckstein wrote: ‘Our enemy is not the aggressor of 1939. Our real enemy is the aggressor of 1917 that occupied the country’.

This book unfortunately omits Gluckstein’s activities during the war. In 1940 he was one of the leaders of Brit Spartakus which attempted to dissuade Hebrew University students from enlisting in the British armed forces to fight Nazism. Like many Trotskyists at that time, the political line was that this was a war of rival imperialisms — one as bad as the other. He was imprisoned in Mazra prison by the British at the beginning of the war — together with figures such as Avraham Stern of ‘the Stern Gang’. Stern later sent an emissary to the German Legation in Beirut.

Three out of the original four Matzpeniks have passed on with Moshe Machover, now in his mid-eighties, the sole survivor. In and out of the British Labour party, he was a strong believer that Jeremy Corbyn would lead the masses to socialism.

This is an absorbing book, based on intensive research, because it is more a history of the international Jewish far Left and its origins rather than Matzpen itself. It is also a work that connects the far Left in Israel with its counterparts in the UK and elsewhere in Europe.

Even so, until the revolution finally breaks out, Moshe Sneh’s admonition that Matzpen had failed to learn the lessons of history continues to ring true.