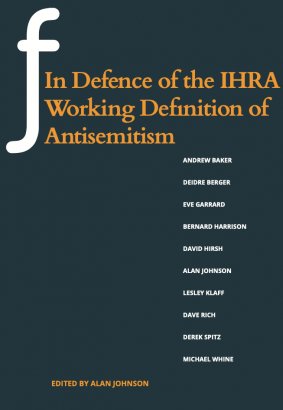

Fathom has published a new eBook about the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism, which you can DOWNLOAD HERE.

In Defence of the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism features Andrew Baker, Deidre Berger, Eve Garrard, Bernard Harrison, David Hirsh, Alan Johnson, Lesley Klaff, Dave Rich, Derek Spitz and Michael Whine.

Andrew Baker, Deidre Berger and Michael Whine put the record straight about the origins and authorship of the IHRA definition. In this crystal clear presentation, the authors explain the origins of the definition after a rise in global antisemitism and an evolution in its form, and describe the process by which the working definition and its accompanying examples came to be written.

Dave Rich, Head of Policy at the Community Security Trust (CST) replies to a letter published in The Guardian on 7 January 2021 from eight lawyers who claimed that the IHRA definition of antisemitism undermines free expression. The signatories also claimed that examples included in the IHRA definition have been ‘widely used to suppress or avoid criticism of the state of Israel.’ Rich argues that the letter rests on a ‘misrepresentation of what the definition says and does’, ‘unevidenced claims’ about its impact, and confusions about its legal status and power.

David Hirsh, senior lecturer in Sociology at Goldsmiths, replies to 40 UK-based Israeli academics, broadly from the anti-Zionist left, who issued a ‘call to reject’ the IHRA definition. ‘The IHRA highlights the possibility of antisemitism which is related to hostility to Israel’ he contends, ‘because that is a significant part of the antisemitism to which actual Jewish people are subjected in the material world, as it exists’. Calls to reject the definition, he argues, are ‘not concerned with the constructive work of describing and opposing antisemitism,’ but only with ‘the purely negative work of rejecting efforts to do so’.

Bernard Harrison, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sussex, and Lesley Klaff, senior lecturer in law at Sheffield Hallam University and Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism, show that critics of the Definition tend to think that a subjective, intentional ‘hostility towards Jews as Jews’ is all that the term antisemitism can mean. This, they argue, is an impoverished and ahistorical reduction of the phenomena of antisemitism, a reduction that the Definition precisely, and to its credit, avoids.

Lesley Klaff and Derek Spitz, a barrister at One Essex Court Chambers, explain why the 2010 Equality Act does not render adoption of the IHRA definition redundant, as is sometimes claimed. In fact, the two are complementary. They argue that as the 2010 Equality Act offers no guidance as to what constitutes antisemitism, it is necessary to look for guidance outside it. The same consideration applies to university anti-harassment codes.

Eve Garrard examines the complaint that the IHRA does not give us a water-tight definition able to tell us definitively which people, language, acts and practices are antisemitic in every single instance. With some help from Wittgenstein, Garrard explains why this demand is misconceived, mistaking how definitions work in general and how the IHRA definition is supposed to work in particular.

David Hirsh responds forcefully to David Feldman, a prominent opponent of the IHRA definition, who argued in The Guardian that the adoption of the IHRA’s clear and specific protections against antisemitism by a university would ‘privilege one group over others’. Later, a group of UK-based Israeli academics agreed with Feldman, suggesting the IHRA should be opposed because it ‘singles out the persecution of the Jews’.

Alan Johnson notes that criticism of Israel, as of any nation-state, is explicitly accepted as legitimate by the IHRA definition, a fact so important, yet so routinely ignored by the critics of the definition as to suggest a deliberate repression on their part. But Johnson also observes that antisemitism has taken on radically different forms throughout history, with endless variations on a core demonology. Today, there is a new antisemitism focused on a demonology of the Jewish state and those who support its right to exist, ‘the Zionists’ or ‘Zios’. He explains why the Nazi analogy – the claim that the Jewish State is equivalent to Hitler’s Third Reich – is one of the most malevolent expressions of this new antisemitism. The IHRA examples, he contends, help us to grasp the nature of this new antisemitism and so to take steps to combat it.