From reforming the banks to the crisis in the Eurozone, from increasing Haredi employment to reducing social inequality, the next government certainly has its work cut out.

Israel operates an open economy that is highly dependent on global trade in goods and services, as well as inward investment flows. The next Prime Minister will find an in-tray overflowing with economic issues requiring urgent attention.

Reforming the banks

Israel’s economy may have survived the ‘great panic’ of 2007-2009 better than most Western democracies, with its banking system relatively intact, but the structure of that system, dominated as it is by a handful of big institutions, as well as the shape of financial supervision, are far from ideal. A note released by the International Monetary Fund in November 2012 on ‘Crisis Prevention and Management’ points to the extensive work that will need to be done by the next government if it is to have the core institutional strengths to deal with the next tsunami, from wherever it may come. (‘Israel: Technical Note on Crisis Prevention and Management’. IMF Country Report No.12/304 November 2012.) It noted that while ‘most of the large financial institutions in Israel came out of the global financial crisis relatively unscathed, the experience of other countries provided ample evidence of the importance of having a robust framework for identifying, mitigating and managing systemic risks.’

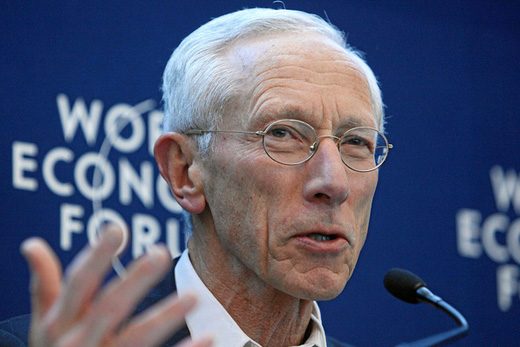

Israel’s monetary and financial stability in recent times is partly down to its ability to attract to the Bank of Israel as governor some of the greatest global practitioners in economics. Among recent incumbents have been Josef Frankel, a former chief economist at the IMF; the late Michael Bruno, a former World Bank chief economist and the current incumbent Stanley Fischer, a former deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund. It is time for solid structures as well as steller appointments.

Maintaining growth

The encouraging news is that in a world of commercial turmoil and financial basket cases, Israel’s economy is relatively stable. The country’s November 2012 military operation ‘Pillar of Defence’ brought the economy to a temporary halt as reservists were mobilised and production in the Southern part of the country came to a standstill. Yet the total costs, including the mobilisation of the Iron Dome missiles, came to an estimated $600 to $750 million. That amounts to just 0.1 per cent of gross domestic product and the country may yet reap rich export rewards if, as expected, there are worldwide orders for the Iron Dome anti-missile defence system that worked with such remarkable accuracy.

Israel emerged from the great financial crisis in far better condition than many of the OECD advanced countries. The banking system was resilient and did not load itself up with the contaminated sub-prime debt that damaged so many American and European banks. In the immediate aftermath of the Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008, production in the Israel economy dropped sharply from 4 per cent to 0.8 per cent. However, and remarkably, the country managed to avoid the worldwide recession and sharp drop in international trade. The pickup was rapid in 2010 with a 4.8 per cent expansion followed by 4.7 per cent in 2011. As fiscal and monetary policy was tightened in 2012 output subsided to a projected 2.8 per cent.

Strong growth has helped to pull down the jobless rate from 7.3 per cent in 2007 to 5.7 per cent in 2011, the year of the ‘cottage cheese’ protests. Within the unemployment numbers there are some concerns, notably the 15.7 per cent jobless rate for young males between the ages of 15-24. Also troubling are labour participation rates that are among the lowest among the OECD countries. This largely reflects the position of Arab-Israeli women and Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) men. The wage levels in these communities are far lower than across the rest of the country leading to high incidences of poverty. The IMF estimates that if employment and wages in these groups were on a par with others in Israel then output would be 15 per cent higher than is currently the case. However, even this is mild stuff when set against the situation in much of Continental Europe, with Spain’s youth unemployment rates, for example, running at well above 50 per cent.

Securing export markets

The biggest threat to Israel’s prospects will be the health of the European economy. Exports comprise 40 per cent of Israel’s national income and one-third of those go directly to European Union; the proportion is even higher if goods that take indirect routes are included. The crisis in the Eurozone will test the mettle of Israeli policymakers.

In the final months of 2012 almost every major European economy, including that of Germany, moved into recession. The most badly affected countries were those of the ClubMed – Greece, Spain and to a lesser extent Italy. As 2012 ended industrial production was plunging in Germany, France found itself in severe difficulty and the path to European fiscal, monetary and banking union – seen as the only way of keeping the euro ideal alive – was strewn with obstacles. In much the same way as the British economy looked in danger of being dragged into a ‘triple dip’ recession by events in Continental Europe, so does Israel, with its heavy exposure to EU markets.

The only saving grace for Israel on this front is its strong economic and financial ties to the United States, where recovery does seem well entrenched, and the hope that the Leviathan gas fields off Israel’s North-East coast could provide it with the energy security the country has craved since its inception.

The country’s main export strengths are in high technology goods, including electronics, pharmaceuticals and communications. The good news is that all of these sectors tend to be more recession-proof. Next to Silicon Valley, it is Israel with its science based universities, such as the Weizmann Institute and Haifa Technion, that is the next most important start-up region, partly assisted by its leading-edge military technologies. Demand for high-tech components and advances is insatiable among the prosperous classes in the West and seems impervious to recession.

Similarly, Israel’s mature generic drugs industry – epitomised by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries – also finds its products in demand as budgets have been squeezed across Europe and the world’s hospitals and doctors have sought to source generic, rather than more expensive branded medicines. It was hugely important to Israel that in October 2012 the European Parliament resisted an attempt to impose a Palestinian-inspired boycott on selected Israeli pharmaceutical products. Nevertheless, a global recession in 2013 would hit exports and foreign trade hard and make it more difficult to hit the projected growth target of 3.8 per cent for the year. The latest projections envisage exports of goods and services climbing by 6 per cent in 2013, after dipping by 4.4 per cent in 2012. An improved export performance together with a moderation of imported goods would assist in bringing the country’s current account – in deficit for the last two years – close to surplus.

Clearly, Israel also faces trade challenges from the turmoil in the North Africa & Middle East (MENA) region. The violence in Syria, continued turbulence in Egypt, dissonance in the Lebanon and strained relations with other regional powers directly affects Israel. The focus on security diverts attention from economic decision-making, impacts on consumer confidence and international confidence and places strains on the public finances. Israel is, however, well placed to cope with these strains. Inward investment, capital flows and exports have helped it strengthen its currency reserves that have increased steadily since 2007 to stand at $77 billion. That is enough to support ten months of imports and represents more than 130 per cent of the country’s overseas debt. Net international investment has been rising and now represents 6 per cent of national income. The most notable global acquisition was the $4bn purchase of Iscar Metal Industries by American investment guru Warren Buffett in 2006.

Fiscal stability

At a time when budget deficits have become the main indicator followed by global markets, Israel has sought to stabilise its fiscal position by putting in place firm rules. The 2010 Deficit Reduction and Budgetary Expenditure Law sought to automatically lower spending until the public debt hit 60 per cent. The number has been gradually coming down, from 78 per cent of GDP in 2007 to 72.3 per cent in 2013, and this at a time when deficits and debt are moving in the wrong direction across much of Europe, Japan and the United States. However, with defence and security spending running at 7 per cent of output and the situation in the region so unsteady, as seen by the events in Gaza and Southern Israel in November 2012, the country lacks the room to manoeuvre that other Western societies enjoy. In the Israeli political context guns always trump butter. If anything, the Arab uprisings of the last two years – rooted in surging food prices, rising youth unemployment and the aspiration for more freedom – have served to underline the importance of defence and security as the tumult has crept ever closer to Israel’s borders. Neighbourhoods, such as the Golan, where the guns have been quiet since the 1973 war, have come back into the military equation.

Social solidarity

One of the more troubling aspects of Israel’s economy is that the spoils of prosperity have not been more evenly spread. Income inequalities in the Jewish state are some of the widest in the advanced world.

The dissonance in society was symbolised in the summer of 2011 by the so called ‘cottage cheese’ rebellion, the far milder equivalent of the Arab spring and the ‘occupy’ movements on Wall Street and the City of London. The high costs of food was at the heart of the rebellion, as it was in much of the MENA region, but behind it was more troubling economic inequalities. A study by the Bank of Israel in 2010 found that some 20 business groups ‘nearly all of family nature and structured in a pronounced pyramid form, continue to control a large proportion of public firms (some 25 per cent of firms listed for trading) and about half market share.’ A separate study by Citigroup estimated that the ten largest businesses actually own 30 per cent of the total market capitalisation or value of the stock exchange.

To understand how out of whack this is, note that the figure is 20 per cent in Germany (where family control remains strong) and 5 per cent in Britain where a more extreme form of Anglo-Saxon capitalism operates.

The standard economic measure of inequality in any society is known as the gini-coefficient. The Paris-based OECD, that keeps tabs on these matters, says that Israel’s inequality is one-fifth higher than the average across the organisation. In only four countries of the OECD’s membership of 34 nations is this measure higher. Shockingly, the OECD found that one-quarter of Israeli families live below the poverty line. The combination of Haredi families and Negev Arabs at the bottom of the economic tree and the oligarchs at the top has made modern Israel a much less equal society than the original Zionist pioneers, creators of the Kibbutz movement, envisaged.

The Trajtenberg Committee, set up by the Netanyahu government in 2011 in response to the social protests, sought to address some of this inequality through the tax system. Proposed reductions in income and corporation taxes have been suspended so the top rate of income tax remains at 46 per cent (against 45 per cent in the UK) and the corporate tax rate at 24 per cent against the 18 per cent proposed. In an effort to capture some of the taxes of the better off and the super-rich, taxes on investment income, capital gains and dividend income in shares have been raised. Steps to assist the less well-off included the suspension of proposed energy taxes and new tax breaks introduced for poorer families. Measures also have been proposed aimed at cutting the housing costs for poorer families.

Adjustments to the tax system will make a difference to social inequality over time. But there is no escaping the fact that Israel needs to address the fundamental problems at both ends of the income scale more aggressively. As Israel has moved from being a developing economy to an advanced economy the concentration of economic power in the hands of the few may have been beneficial. But as new wealth flows, partly as a result of the energy independence from the Leviathian field, the Knesset must find ways of spreading that wealth around.

Israel could learn one thing from the United States. The country’s opposition to the build-up of over-powerful trusts is fundamental to American thinking. At the turn of the 20th Century, the Rockerfeller trust, Standard Oil of New Jersey, was ruthlessly broken up into several dozen companies leading to far wider share ownership. In more modern times AT&T and IBM suffered the same fate. It is not hard to imagine that Apple will at some time in the future be broken up. In Israel, Scailex, Discount Investment and Koor, among others, could benefit from the same kind of treatment.

At the other end of the scale the improved benefits being put in place will ease poverty. Moreover, the efforts to bring Charedi Jews into the defence forces ought to make those who have served more economically viable in the future. In the Negev, efforts to move Bedouin into proper communities with adequate education and social support should help. Israel has a golden opportunity to enable the Israeli Arabs to prosper as an economic group.

Conclusion

Israel has moved from an agricultural to an industrial to an advanced high-technology economy. It is a remarkable success story. Along the way its economic management also has become far more sophisticated, matching that of the advanced West in its ambitions. Society and government now needs to move on again. Markets have to be made fully competitive, even if that means tough action against the controlling businesses. And the political classes need to learn that economic security and a more homogeneous society is as important to the future as defensible and safe borders.