In the elections for Israel’s 19th Knesset the success of Benjamin Netanyahu almost proved to be his downfall.

What should be obvious is that the majority of the public identified with the Prime Minister’s ability to present Israel’s legitimate case before the world. They supported his moves in Jerusalem and tolerated, to a large extent, Israel’s presence in Judea and Samaria. In poll after poll over the last two decades, we see a dichotomy: Israelis desire peace very much and are willing to offer much to obtain it, but they do not believe that a peace agreement is achievable and they believe even less that the Arabs would preserve that peace.

Confident in Netanyahu’s handling of Israel’s external threats, Israeli voters felt able to vote based on their lack of confidence in their day-to-day lives. Thinking Netanyahu was already confirmed as Prime Minister, some voters presumed they had a virtual ‘double-ticket’ and sought out someone else. The voters were dissatisfied with his domestic social programs, or lack thereof, not his foreign and security policies. They were convinced by promises of cheaper housing, less expensive utilities and a fair share of the burden of military service, and, drawn by their desire to be ‘the middle class’, some abandoned the Likud.

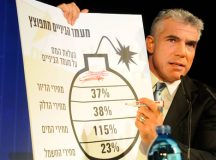

Israel’s voters have a history of searching for a secular savior outside the usual party groupings. In 1977, the Dash Movement for Change obtained 15 seats. In 1999, there was the Center Party with six. In 2003, Yair Lapid’s father, Tommy, broke out with 15 seats for Shinui. In the end, they all dissipated, either disappearing or merging into other frameworks. The challenge facing Yair Lapid is how to manage his own success, avoiding his father’s near-hatred for the Haredim, and maintaining an organisation able to outlast one Knesset term – which, given the coalition puzzle yet to be completed, might well be less than four years.

As for Netanyahu, politics, it seems, is truly the profession in which you don’t have to say you’re sorry. Striding out onto the stage to address the Likud faithful on election night, he declared, ‘The public wants me to continue leading the country to form a coalition’ – despite ‘succeeding’ in losing some 10 possible seats.

I am still puzzled as to why the Likud chairman called for elections in early October but, after doing so, he made too many mistakes. He declared himself strong but displayed weakness; he presented the Likud-Yisrael Beiteinu list as broadly-based and representative but concentrated the election campaign on himself; he signed a ‘remainders agreement’ with the Bayit Yehudi list – to ensure that all the votes left over after the first division by the 120 quotient would remain in the Likud camp – but then consistently attacked that party.

The election saw the reinvigoration of the religious-nationalist camp. The leader of Jewish Home, Naftali Bennett – observant until army service, married to a secular woman but now firmly back into the old Mizrachi mold – emerged as the new hope. His service as executive secretary of the Yesha Council was refreshing and he was able to alter the perspectives of the non-ideological public as well as changing the way the entertainment and cultural icons of ‘the state of Tel Aviv’ viewed the reality on the ground in Judea and Samaria. True, the loss of almost 70,000 votes to the more radical Otzma LeIsrael party hurt, and Netanyahu’s personal animosity to Bennett resulted in him being the last to be called in the first round of coalition consultations for the next government. But Netanyahu cannot shun the 12 new Jewish Home MKs, just as Lapid cannot accept a Haredi list.

Despite Netanyahu’s success in defending the across-the-‘Green Line’ communities and permitting their continued growth, they trust him less after the ‘two-state’ pronouncement, the refusal to adopt any element of the Levy Report and his alliance with Ehud Barak, whose ministry-supervised activities in the territories vitiated against a vote for him. This distrust intensified following the Likud’s anti-Bennett ads.

So, Netanyahu will set up his coalition but his very success in dealing with Israel’s external challenges means he must share power with Yair Lapid, a successful political amateur leading a party top-heavy with 18 novice MKs and Naftali Bennett, new and successful too, and who will now need to balance his ideological constituency with the new social concerns agenda.