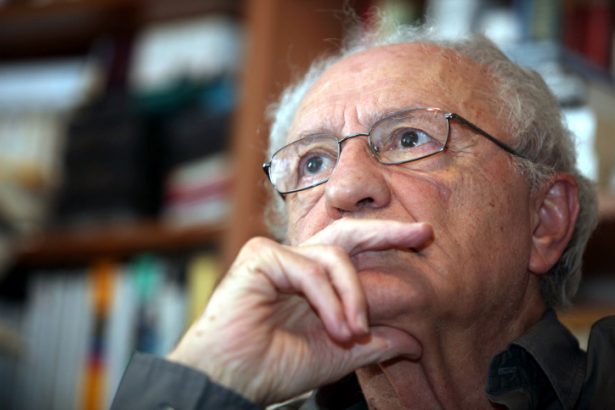

Fathom Editor Alan Johnson reflects on the life and work of Zeev Sternhell who died this week.

Obituary notices following the death of the intellectual historian Zeev Sternhell have focused on the brilliance of his academic scholarship on fascism and his political opposition to the continued Israeli presence in the territories, as well as his related fear that decades of ruling over another people would eventually erode Israeli democracy itself. All this is reasonable, for those were indeed his central concerns. But Zeev Sternhell was also a trenchant critic of a certain kind of anti-Zionism and he was one of the few who saw Left-Fascism plain. As both these contributions seem to me to have been somewhat neglected thus far, and as both can help us orientate ourselves politically today, I focus on them here.

The Life

Born in Przemyśl, Poland, Sternhell lost his father in World War Two when he was five. His mother and sister were murdered by the Nazis, an aunt and uncle getting him to Lwow where he lived as a Catholic with false papers. After the war, in France, he renounced his Christian identity, before moving to Israel in 1951, alone, aged just 16. A platoon commander in the Golani infantry brigade, he fought in the Sinai War and as a reservist in the Six-Day War, the Yom Kippur War and the 1982 Lebanon War.

He taught political science at the Hebrew University from 1966, was soon recognised as one of Israel’s greatest intellectual historians, and was eventually elected the Leon Blum Chair of Political Science at the University. His genuinely original intellectual contribution, I suggest, was to help us understand that European fascism was ‘neither Right nor Left’ (the title of his brilliant study of inter-war French fascism) but rather an outgrowth of the European Counter-Enlightenment that drew on the hostile responses from both Left and Right to modernity, democracy, liberalism, individualism, capitalism and parliamentary reformism.

In 2008, he was awarded the Israel Prize for Political Science. Also in that year, Sternhell was wounded by a pipe bomb placed outside his Jerusalem home by an ultra-nationalist fanatic. Sternhell’s hopes had been raised high by the Oslo Accords. ‘In the history of Zionism’ he wrote, ‘the Oslo agreements constitute a turning point, a true revolution. For the first time in its history, the Jewish national movement recognised the equal rights of the Palestinian people to freedom and independence.’ In his last years, Sternhell could seem understandably despairing about the state of the peace process, the growth of the settlements he had controversially called a ‘cancer’ and the prospects for Israeli society. But I am not aware that he ever gave up his hope that Zionism, his Zionism, would be reclaimed, so to speak, and two states for two peoples would be brought into being.

Critic of Anti-Zionism

‘The establishment of the state was like the creation of the world for me,’ Sternhell once said. ‘It transported me to a kind of rapture. I am not only a Zionist, I am a super-Zionist.’ He went on: ‘For me, Zionism was and remains the right of the Jews to control their fate and their future. I consider the right of human beings to be their own masters a natural right. A right of which the Jews were deprived by history and which Zionism restored to them. That is its deep meaning.’

While he criticised the Israeli Right in the sharpest terms and supported a boycott of the settlements (‘but not Israel’ he would swiftly add) Sternhell also criticised ‘the extreme politicisation of anti-Zionist discourse’ and opposed the way scholarship had often become polemic, weaponised in ‘an all-out intellectual war against Zionism’.

His essay, ‘In Defence of Liberal Zionism’, published in New Left Review in 2010 was an extended review of an anti-Zionist book he said was of high calibre and general culture, Gabriel Piterburg’s The Returns of Zionism: Myths, Politics and Scholarship in Israel, but which still demonstrated ‘the usual faults of the genre’, not least in its use of the concept of ‘settler colonialism’.[i] Sternhell began with a warning: ‘This review of … a work by a convinced anti-Zionist, has been written by a Zionist who is no less sure of himself’.

Anti-Zionism, Sternhell felt, tends to distort history. For example, although the 1947-9 war was ‘launched by the Arab states against the founding of the Jewish state’, he pointed out that Piterburg could only see one cause, the ever-racist ideology of Zionism. More or less ignored by Piterburg were the long-range rise of a much more volkish Europe, along with mid-century European fascism, the defeat of world revolution (and with it the hopes of the Bundists and the revolutionary Left), the Holocaust, and the Arab war against the Jewish state.

The concept of ‘Zionist Settler Colonialism’ is a theorisation of this kind of keyhole history of the conflict. The Jews of Palestine are framed as just another set of ‘racist white European settlers’, a bit late to the show perhaps, but essentially no different than those earlier waves of racist European settlers to America, Canada, South Africa, Argentina, Australia and New Zealand. The claim, Sternhell wrote, simply ‘does not correspond to historical reality’.

While Sternhell accepted that ‘the Jewish national rebirth has demanded an exorbitant price from the Arabs’, he noted that the concept of ‘settler colonialism’ excluded more or less everything that a properly materialist historical account of Zionism would have to include. A brief list:

- the historical relationship of Jews to the land, utterly unlike any ‘settler colonialists’;

- the sheer material weight of European history as a driver, in the form of the collapse of the post-1789 liberal and emancipatory society and the Enlightenment conception of the nation, and, accompanying those changes, the radicalisation of European anti-Semitism, culminating in the Holocaust;

- the local character of about half of Israeli Jews; Arab speakers moving within a region they had lived in for millennia, and who were, note, under the boot themselves. Sternhell thought that to accuse those Jews ‘forced out of the Arab countries as a result of the founding of the State of Israel’ of having a ‘colonialist mentality’ was just ‘absurd’;

- the international community mandate to nurture a new Jewish state (as was happening for Arab peoples at the same time in the same region);

- the sheer plurality of historical Zionist subjectivities, from which the anti-Zionist, like a prosecuting attorney, tends to cherry-pick and quote-mine until all that remains is a conveniently racist ‘typical settler consciousness and imagination’ (Piterburg’s words).

Of the agency and moral responsibility of every actor other than the Jews, the anti-Zionist may often say absolutely nothing. Sternhell gives the example of the treatment of Herzl by Piterburg. Here was a liberal who saw a storm coming, a European who, after losing his faith in liberal Europe, reluctantly decided the Jews needed to create a state of their own. Yet Piterburg depicted an anti-liberal reactionary and a racist. Sternhell objected:

Herzl knew what every cultivated Jew understood: namely, that the fate of the Jews depended on the fate of the liberal and emancipatory society that had emerged from the French Revolution of 1789 … [but he saw] the liberal order in Western Europe was tottering … [and] the future of the Jews in the whole of Europe was at stake.

Herzl also understood that a major change in the very conception of the nation was overtaking Europe. The Enlightenment concept of the nation, Sternhell writes, had been a ‘heroic attempt … to overcome the resistances of history and culture, and affirm the autonomy of the individual’, but it was ‘dead and buried’ by the end of the 19th century. ‘What emerged from the ruins of the Enlightenment was the idea of a tribal society, tightly grouped around its racial core, its churches and its cemeteries, in which the Jews would not only always be a foreign element, but their rights as men would be worth no more than the paper they were written on’

It was partly seeing, partly intuiting the results of that change, insisted Sternhell, that drove Herzl’s Zionism. In a striking image of no little visceral power he reminded Piterburg that ‘Half a century before the Shoah, Europe thus began to vomit up its Jews: bodily in Eastern Europe, ideologically on both sides of the Rhine.’ The creation of a Jewish homeland became nothing less than an ‘existential necessity’ given how history went. Jewish nationalism should be understood as ‘first of all a defensive reflex … simply giving, in contact with the other nationalisms of the time and place, a concrete political expression to Jewish identity’. Anti-Zionism, by contrast, ignores the tragic groundtone of the conflict, in order to substitute a simple morality tale: there was a very late, Jewish chapter to the long sorry history of White European Racist Colonialism. Sternhell, perhaps rather optimistically, thought this tale ‘hardly credible outside fiercely anti-Zionist political circles’.

Sternhell thought anti-Zionism could move from a history with no place for the Jewish tragedy to a politics with no place for Jewish peoplehood. We see this so often today: only the Jewish homeland is to be ‘smashed’ (this even after the Holocaust), only Arab nationalism is coded as necessarily progressive (whatever it actually does), while magical thinking about the rosy future of the Jews as a stateless minority in the Arab Middle East allows the anti-Zionist to sustain his or her belief in the so-called ‘one state solution’.

Once the anti-Zionist has bracketed the history that produced both Zionism and Israel, he or she is then free to reframe the Jewish in-gathering as a racist and colonial project, a dirty and clannish affair, driven by supremacism. This, in turn, legitimates a politics of what we might call, with Sean Matgamna, ‘Absolute Anti-Zionism’, which seeks to eradicate the Jewish homeland completely. Sternhell observed that Piterburg ‘holds that Israel can only obliterate the original sin of its birth by disappearing’. Today, that political programme often converges with Arab nationalism, radical Islamism and even antisemitism. In these murkey borderlands, the far Left meets the far Right, a phenomenon Sternhell had also studied as a historian of European fascism.

Anatomist of Left-Fascism

Sternhell changed our understanding of fascism by showing us that it was ‘neither Left or Right’ but a hybrid of anti-Enlightenment ideas and sensibilities found on the Left and the Right. And he warned us that it was not some passing conjunctural political event, but had its roots deep in European civilisation. As Robert O. Paxton put it in The New York Review of Books, when reviewing The Birth of Fascist Ideology, ‘[Sternhell] shows irrefutably that fascist doctrine had complex cultural origins, drawing not only from conservative efforts to adapt to the novel requirements of mass politics, … but also from dissent within the left against the materialism, positivism, and reformism that mainstream Marxism shared with social democracy in the 1890s.’ So much of the disarray and disgrace of the contemporary left is rooted in that ‘dissent’, that disastrous turn to voluntarism, violence and dictatorship in the 1920s, but that is a topic for another day.

In inter-war Europe, Sternhell showed in Neither Right nor Left: Fascist Ideology in France, parts of both the Left and the Right detested ‘the established disorder’ of materialism, liberalism, parliamentary democracy and bourgeois society. They both cultivated a ‘distaste for the lukewarm,’ and both had a fascination with ‘the idea of a violent relief from mediocrity’. Inter-war European left-fascist movements, periodicals, and thinkers, Sternhell argued, helped to create the intellectual climate that eroded the moral legitimacy of an entire civilisation and fostered an inchoate ideology of revolt based on the glorification of will and the cult of revolutionary violence.

Parts of today’s far Left are infused with this spirit, heir to the raging ‘contempt for the Enlightenment, “bourgeois society,” parliamentarism and democratic socialism’ that Sternhell thought had fostered a kindredness between the inter-war Left and fascism, and had made possible the hybrid political form – linksfaschismus, or left-fascism.[ii]

Sternhell showed us the fascism of the national socialist Edouard Berth, author of Satellites de la ploutocratie, who said in 1912 that only violence could stop French culture ‘becoming universally bourgeois’. And of the Frenchman Drieu La Rochelle, who argued in Socialisme fasciste (yes, there were books and pamphlets with titles like that between the wars) that the ‘incentive of lucre’ [i.e. money] must be replaced by the ‘incentive of duty’ because ‘the foundation of moral force [is] a disposition to sacrifice, a will to fight’. We do not need to think we are living through a simple repetition – for we are not – to see the value in Sternhell’s insights.

Though we corresponded a little, I never met Zeev Sternhell. One who did was the human rights lawyer Michael Sfard, who spoke at the funeral. He recalled to the mourners that he had asked for Zeev Sternhell’s help eight years ago in a case that involved a libel suit against a group of activists that had publicly called an organisation a ′fascist movement’. He shared his memory with the mourners. ‘On the day he had to be interrogated by the prosecutor’s lawyer I waited for him at the entrance to the Jerusalem district court. When he got out of the taxi I saw that he was holding the collection of materials I gave him to prepare his opinion: articles of the right-wing movement people, their brochures, pamphlets and a horrifying book that one wrote. This Professor Emeritus, member of the National Academy of Sciences, winner of the Israel Prize, whose books were translated into dozens of languages, came to court like a hardworking undergraduate student arrives for the end of the year exam.’ Sfard’s tribute, that Sternhell was a ‘one-time combination of intellectual greatness with moral power’ will be shared by many.

References

[i] Zeev Sternhell, ‘In Defence of Liberal Zionism’, New Left Review 62. March-April 2010.

[ii] Alan Johnson, ‘Slavoj Žižek’s Linksfaschismus’, in Michael J. Thompson and Gregory Smulewicz-Zucker, eds., Radical Intellectuals and the Subversion of Progressive Politics: The Betrayal of Politics, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.