Perversely, the atrocities of 7 October, have achieved their goal of reviving Palestinian statehood. The Western world seems to want to make Sinwar into a latter-day Saladin, who at the head of Hamas’ terror army, chased off the modern Crusaders and liberated Jerusalem? Russell Shalev argues that until Palestinian society undergoes a radical reevaluation of its foundational values and accepts mutual recognition of Jewish national claims, the idea of a Palestinian state must be moot. For other recent Fathom discussion of the question of recognition, see Paul Gross (also against recognition at the present moment) and Jack Omer-Jackaman (for).

Little over half a year since Hamas’ barbaric attacks on 7 October, Palestinian statehood is high on the international agenda. On 10 May 2024, the United Nations General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to accept ‘Palestine’ as a full member state. The vote is largely symbolic after the United States vetoed ‘Palestine’s’ bid at the Security Council. However, General Assembly membership adds to the growing pressure on Israel to make dangerous concessions towards the Palestinians. Perversely, the atrocities of 7 October, which clearly harken back to the darkest times of Jewish history, have achieved their goal of reviving Palestinian statehood.

The resurrection of the ‘two-state solution’ takes many forms. According to reports in the Wall Street Journal, the Biden administration is tying normalisation between Israel and Saudi Arabia with a renewed push for Palestinian statehood. In March, nineteen Democratic senators sent a letter to President Biden, calling for ‘bold’ action for a Palestinian state. Other states have expressed their impatience with such formalities as bilateral negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians, with at least five European Union member states announcing their intention to recognise a Palestinian state soon. EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell has stated that ‘Israel cannot have the veto right to the self-determination of the Palestinian people,’ meaning that Palestinian statehood and the myriad of serious challenges to Israeli safety and security are none of Israel’s business

Within several months, the International Court of Justice is expected to issue its advisory opinion decision on ‘Legal Consequences arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem’, which from its biased question will likely find an Israeli occupation in violation of international law. Without a doubt, an ICJ opinion hostile to Israel will add to growing pressure on Israel to withdraw from areas claimed by the Palestinians.

The renewed impetus for a Palestinian state in Judea, Samaria, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, whether by unilateral recognition or through bilateral negotiations coupled with heavy diplomatic pressure on Israel, ignores the very real issues that have prevented Palestinian statehood until now. In the post-7 October world, these issues all but guarantee that the move towards a Palestinian state will encourage Palestinian intransigence and endanger Israeli security.

Will Sinwar be the father of Palestine?

In the aftermath of the 7 October massacres, the international community has fallen for Hamas’ playbook. One month after Hamas’ bacchanal of rape, torture, murder, and kidnapping of over 1,400 Israelis, a senior Hamas politburo member explained that the Islamist group sought to revive the Palestinian issue with a dramatic flair. Theatrically slaughtering Jewish families in their homes and live-streaming it on GoPro cameras was the necessary drama. Speaking to the New York Times, Khalil al-Hayya, a senior Hamas official in Doha, said that it was necessary to ‘change the entire equation and not just have a clash … We succeeded in putting the Palestinian issue back on the table, and now no one in the region is experiencing calm.’ As he put it, ‘what could change the equation was a great act, and without a doubt, it was known that the reaction to this great act would be big… We had to tell people that the Palestinian cause would not die.’

In the months since Hamas’ invasion and slaughter, support for the jihadist group has surged and remains high among Palestinians in Judea, Samaria and Gaza. According to a survey conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research in March 2024, 71 per cent of respondents supported Hamas’ decision to launch the 7 October attack and 75 per cent of Palestinians believed that 7 October revived international attention to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. 64 per cent of Palestinians in Judea and Samaria and 52 per cent of Gazans believed that Hamas should continue to rule Gaza after the war, as opposed to the Palestinian Authority. Finally, 70 per cent of Palestinians expressed satisfaction with Hamas, with support for Hamas by Gazans increasing by 10 per cent since December; half of Palestinians selected ‘armed struggle’ as the most effective way to achieve a Palestinian state, as opposed to negotiations or popular non-violent resistance.

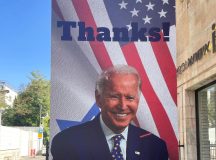

Faced with the reality of widespread support for Hamas and the events of 7 October, the overwhelming majority of Israelis currently oppose the creation of a Palestinian state. If the international community responds to 7 October by sanctioning Israelis while rewarding Hamas for its atrocities, Palestinian society will understand that Hamas’ ‘armed struggle’ strategy was successful. The United States, the European Union, and Western states would crown Yahya Sinwar as the father of Palestine, ending any hope for an embrace of peaceful or tolerant Palestinian attitudes towards Israel. Does the Western world want to make Sinwar into a latter-day Saladin, who at the head of Hamas’ terror army, chased off the modern Crusaders and liberated Jerusalem?

A Palestinian State would not be ‘peace-loving’

The United Nations General Assembly resolution recognising ‘Palestine’ betrays the lofty goals for which the organisation was originally intended. The history of the so-called peace process demonstrates conclusively that the Palestinian leadership as well as Palestinian society are not ready to accept the permanence of Israel’s existence as the nation-state of the Jewish people, or to give up their dream of ‘Palestine, from the river to the sea’. There simply are no Palestinian leaders or political movements ready to reconcile themselves with Jewish nationhood in Israel. That the Palestinian vision of a state in the pre-1967 lines is as a stepping stone towards irredentism and the reversal of the 1948 war should be enough to disqualify a Palestinian state.

Article 4 of the UN Charter extends membership to ‘all other peace-loving states which accept the obligations contained in the present Charter and, in the judgment of the Organisation, are able and willing to carry out these obligations.’ The General Assembly, in Resolution 506A(VI) (1952) interpreted ‘peace-loving’ as being fulfilled, inter alia, by the maintenance of friendly relations, fulfillment of international obligations, and a willingness to utilise peaceful dispute settlement. These conditions are not ancient history. Upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the European Community developed guidelines on the recognition of new states in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, which required new states to demonstrate among others, commitment to the rule of law, democracy, human rights, rights of minority ethnic and national groups, and the inviolability of national borders. An honest observer should conclude that ‘Palestine’ is not peace-loving, but rather committed to a revanchist struggle against Israel.

Hamas’ genocidal goals and actions are well-known and need no lengthy explanation. Emerging out of the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood into an independent organisation in the 1980s, it is ideologically committed to the destruction of Israel and the establishment of an Islamic state in all of historical Palestine. Hamas emphasises jihad, and violent struggle, as the sole means of achieving its goal. Hamas has invested the war against the Jews with messianic and eschatological meaning. The destruction of the Jews is required for the establishment of the divine kingdom on earth. As described by Professor Meir Litvak:

In the view of Hamas the Palestinian–Israeli conflict is not merely a territorial dispute between Palestinians and Israelis: it is first and foremost a ‘war of religion and faith’ between Islam and Judaism and between Muslims and Jews. As such, it is portrayed as an unbridgeable dichotomy between two opposing absolutes—as a historical, religious and cultural conflict between faith and unbelief, between the true religion that supersedes all previous religions, that is, Islam, and the abrogated superseded religion, Judaism. It is a war between good, personified by the Muslims representing the party of God (Hizballah), and ‘the party of Satan’ (hizb al-shaytan) represented by the Jews. Consequently, the conflict is considered an ‘existential battle, rather than a dispute over borders’ (ma‘rakat wujud wa-la hudud).

These antisemitic and revanchist views are not the sole purview of Hamas. Although American officials have called for a ‘revitalised’ or a reformed Palestinian Authority to return to post-Hamas Gaza, the PA is in no way a moderate entity. Not only has the PA or the Fatah movement refused to condemn the 7 October massacre, but they have alternately praised and promoted conspiracy theories about them. Jibril Rajoub, one possible successor for the 88-year-old Mahmoud Abbas, hailed the attack in November as ‘heroic, an earthquake, an unprecedented event.’ Two weeks after the massacre, the PA issued a document through its Ministry of Religious Affairs instructing mosques to incite antisemitic hatred, quoting the infamous hadith according to which ‘The hour will not come until the Muslims fight the Jews and the Muslims kill them, until the Jew hides behind the stones and trees and the stones or trees say, ‘O Muslim, O servant of Allah, this is a Jew behind me, come and kill him.’ The Israel Defense and Security Forum has thoroughly documented the PA’s hateful reaction to Hamas’ attack. PA security forces have carried out hundreds of terrorist attacks against Israel, a fact of which Fatah boasts. According to Fatah themselves, Fatah members and PA security forces carried out over 1,500 terrorist attacks against Israel in 2023 alone, including a January attack in which a PA lieutenant opened fire on Israeli forces at a checkpoint near Shechem (Nablus). Of course, the PA continues to allocate over USD 370 million to salaries for terrorists in Israeli prisons and their families.

Both Hamas and Fatah share these ideological commitments to terrorism, antisemitism, and opposition to Israel’s existence. Barring radical changes in Palestinian attitudes, a Palestinian state would certainly not be capable of fulfilling its international obligations or respect for human rights.

The rejection of a Jewish state is the core of the conflict

To understand why the current push for a Palestinian state, whether by unilateral or bilateral means, is bound to fail, it is necessary to revisit the failures of previous ‘peace process’ attempts. During the winter of 2000, American President Bill Clinton invited Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and PA leader Yasser Arafat to peace negotiations at Camp David. Barak had agreed in principle to a demilitarised Palestinian state on 92 per cent of Judea and Samaria and 100 per cent of the Gaza Strip; territorial swaps; evacuation of most settlements and concentration in settlement blocs; the establishment of the Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem, including over the Muslim and Christian quarters of the Old City; return of ‘refugees’ to the Palestinian state along with international aid to the refugees. As Dennis Ross, senior negotiator at the Camp David talks, recalled, Arafat’s only contribution to the talks was to insist that the Jewish temple never existed in Jerusalem at all.

Benny Morris, Israeli historian, interviewed Barak in 2002 and explained the meaning of Arafat’s Temple denial:

Arafat, says Barak, believes that Israel ‘has no right to exist, and he seeks its demise.’ Barak buttresses this by arguing that Arafat ‘does not recognise the existence of a Jewish people or nation, only a Jewish religion, because it is mentioned in the Koran and because he remembers seeing, as a kid, Jews praying at the Wailing Wall.’ This, Barak believes, underlay Arafat’s insistence at Camp David (and since) that the Palestinians have sole sovereignty over the Temple Mount compound (Haram al-Sharif—the noble sanctuary) in the southeastern corner of Jerusalem’s Old City. Arafat denies that any Jewish temple has ever stood there—and this is a microcosm of his denial of the Jews’ historical connection and claim to the Land of Israel/Palestine. Hence, in December 2000, Arafat refused to accept even the vague formulation proposed by Clinton positing Israeli sovereignty over the earth beneath the Temple Mount’s surface area.

The rejection of any Jewish historical connection to the land of Israel is not a fringe or idiosyncratic view held by Arafat alone. In 2015, the PA-appointed Mufti of Jerusalem insisted that the al-Aqsa mosque had existed since time immemorial and that the Jewish temple was a myth. In May 2023, Abbas repeated his denial of the Temple’s existence while speaking before the UN Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People and claimed that ‘these countries [the UK and the US] wanted to get rid of the Jews and benefit from their presence in Palestine… [This was] a promise of those who do not own to those who do not deserve. Britain gave Palestine as a gift to Israel. Why Palestine? Give them another island somewhere else.’

In 2008, Israeli PM Ehud Olmert made another offer even more generous than Barak’s 2000 offer, which Abbas ‘rejected out of hand’. Once again, the sticking point was regarding Israel’s permanence as a Jewish state. The Palestinian leadership harbors revanchist fantasies, the so-called Right of Return, according to which millions of descendants of Arabs who fled or were expelled in the 1948 war will return to Israel (not the future Palestinian state), effectively reducing Israeli Jews to minority status. Of course, no Israeli leader, no matter how dovish, could accept such a situation. As Abbas explained: ‘‘I cannot tell four million Palestinians that they have no right of return.’’ Saeb Erekat, the senior Palestinian negotiator, emphasised in a 2010 article in the Guardian, that the right of return remained the core issue. Despite Olmert’s acceptance of the immigration of a limited number of refugees, although far more than any Israeli leader had ever accepted, Abbas turned down the offer as ‘the gaps were wide’.

Even Netanyahu, the supposed arch-hawk and boogeyman of the left, accepted a Palestinian state in principle in the 2009 Bar-Ilan Speech. In 2010, under heavy American pressure, Netanyahu agreed to a ten-month settlement freeze. For the first nine months, the Palestinians refused to negotiate without a freeze to building in Jewish neighbourhoods in Jerusalem as well. Only in the last month of the freeze did the Palestinians decide to join the negotiating table and promptly check out once the freeze expired. George Mitchell, the Obama administration peace envoy, expressed his frustration at Palestinian intransigence:

I personally negotiated with the Israeli leaders to bring about a ten-month halt in new housing construction activity. The Palestinians opposed it on the grounds, in their words, that it was worse than useless. So they refused to enter into the negotiations until nine months of the ten had elapsed. Once they entered, they then said it was indispensable. What had been worse than useless a few months before then became indispensable and they said they would not remain in the talks unless that indispensable element were extended.

Throughout this time, Abbas repeated that he would never recognise Israel as a Jewish state. This goes to the very crux of the matter. Palestinian leadership and society see a Palestinian state as a stepping stone to the ‘complete liberation of Palestine’. Unilateral recognition of a Palestinian state or diplomatic arm-twisting of Israel to accept such a state would guarantee more bloodshed and the continuation of the conflict until the Palestinian national movement comes to terms with Jewish national claims to the land.

Can the Palestinians ever end ‘the Occupation’?

As is well-known, Israelis unilaterally disengaged from the Gaza Strip in August-September 2005, withdrawing both its civilians and military presence. On September 11, 2005, the Government of Israel adopted Resolution 4235, according to which Israel ended its presence in Gaza, and the following day, the Israeli military commander issued a proclamation ending the military government in Gaza. Israel and the PA concluded two agreements regarding border control, and the governance of Gaza was transferred to Fatah until Hamas seized power in June 2007. Israel (and the United States) holds that it is no longer an Occupying Power in Gaza, and this position was upheld in the 2007 Al-Bassiouni Israeli Supreme Court.

Contrary to generally accepted laws of occupation, many prominent international organisations continue to promote the idea that Israel remains an Occupying Power in Gaza. This disingenuousness raises serious questions as to whether even a Palestinian state that takes Israeli security concerns into account can ever satisfy the international community.

The main sources of treaty law for the existence of an occupation are the 1907 Hague IV Regulations and the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949. Article 42 of the Hague Regulations defines occupation as:

Territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army. The occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised.

The basic condition of occupation is ‘effective control’ of the territory. Effective control includes civilian governance of the occupied territory by the occupying forces. Since 2005, Israel has not effectively controlled Gaza and is not the sovereign governing the Gazans’ life in any accepted legal sense. Israel does not manage Gaza’s education or health system, for example, nor does Israel have the ability to appoint Gazan officials. Indeed, it is hard to imagine Hamas building up the massive terror infrastructure and army necessary to carry out the 7 October attack if Israel had maintained ‘effective control’ of Gaza. In two recent decisions by the European Court of Human Rights, the need for effective control was reiterated, finding that ‘physical presence of foreign forces is a sine qua non requirement, i.e., occupation is not conceivable without ‘boots on the ground.’’ [1]

The notion that Israel still occupies Gaza (leaving aside any possible change in legal status following the 2023 Israeli operation) is based on several claims: mainly continuing Israeli control of land borders, airspace, and maritime space, Israel’s theoretical ability to reenter Gaza in response to threats and Gaza’s supposed economic dependence on Israel. These disingenuous claims have been made by major international organisations such as the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, the UN General Assembly, the World Health Organization, the International Criminal Court, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

According to reports, Secretary of State Blinken has asked the State Department to draw up models of a demilitarised Palestinian state. Netanyahu himself proposed a demilitarised Palestinian state most famously in his 2009 Bar Ilan speech, and has repeated the idea several times since. Such a demilitarised Palestinian state would need to include Israeli control of airspace; continued Israeli control of the Jordan Valley to prevent Iranian weapons smuggling, Israeli maritime control as well as special agreements allowing the IDF to operate in the Palestinian state if necessary. Palestinians derisively have referred to such a state as ‘Bantustans’, not even remotely meeting Palestinian statehood demands. Based on Israel’s experience in Gaza, it is likely that much of the international community will continue to see a demilitarised Palestinian state under Israeli occupation. Israel will lose crucial security interests while not satisfying international pressure.

Is a demilitarised state workable?

Even if Palestinians would accept a demilitarised state, it is doubtful that ‘Palestine’ would remain that way or not pose a future threat to Israel.

Costa Rica is often seen as a model of a successful demilitarised state. In December 1948, Costa Rican president José Figueres Ferrer abolished the army, for fear of military uprisings threatening his rule. Costa Rica’s demilitarisation was passed in a 1948 parliamentary decision and then enshrined in Article 12 of the Constitution in October 1949. Starting in 2015 and reaching a peak during the COVID-19 pandemic, local drug gangs killed hundreds of citizens. In 2022, the murder rate reached the equivalent of one killed every 10 hours. In 2015, the government created special heavily armed police units to tackle violent crime. Costa Rica has also cooperated with Colombia and received American funding and training to develop military-police patrol units.

Haiti, largely a failed state, is another example of demilitarisation’s challenges. Haiti abolished its military in 1995. Haiti has been rocked by major gang violence, leading the government to reestablish its military in 2017-2018. From 2010 to 2017, UN peace-keeping forces were deployed in the country. The Security Council approved the deployment of a multinational mission to Haiti in October 2023, with Kenya taking the lead. Kenyan police officers are currently on standby following a Kenyan court decision ruling the deployment illegal.

Palestinian demilitarisation is a catch-22. According to a new report by Khaled Abu Toameh, armed militias are resurgent in northern Samaria, operating in almost every village or town. Most of these militias are composed of members affiliated with Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), and even the ruling Fatah party. The PA itself has little control over some parts of its security forces, let alone the armed gangs. Toameh says that there are still between 3,000 to 3,500 militiamen operating throughout the area. A Palestinian state without sufficient military capabilities could easily be overrun by Hamas, PIJ, or another terrorist group. On the other hand, official Palestinian forces will likely turn against Israel, as they already have. During the Oslo process, Israeli and foreign ‘peace processors’ repeatedly called upon Rabin to prop up Arafat’s PA security apparatus. Not only did the PA not combat terrorism, but Fatah groups such as the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade had a leading role in carrying out deadly terrorist attacks during the 1992-1996 Oslo terror wave as well as the 2000-2005 Second Intifada. How could Israel prevent a Palestinian invitation to Iran or other hostile powers for peacekeeping forces to maintain security?

Conclusion

It is Israel’s supreme interest, as well as that of Western nations opposed to terror, that the Palestinians not be rewarded for the 7 October massacre. Hamas’ goal, besides killing as many Jews as possible, was to revive the Palestinian issue and deal Israel a deadly blow. That goal has largely been met, as the Americans are exerting heavy diplomatic pressure to impose a Palestinian state on Israel, while several key European states are opting to skip negotiations altogether. Having failed at the Security Council, the PA has brought its statehood demands directly to the General Assembly. Israel must prevent crowning Yahya Sinwar as the founder and father of Palestine.

Past efforts of peace-making have failed as the Palestinian national movement refuses to reconcile itself to Israel’s permanence and recognition of Jewish national claims. Despite the deep rivalry between Hamas and Fatah, rejection of Jewish nationhood and statehood is a point of commonality. As long as this is a prevalent view in Palestinian society, a Palestinian state, whether achieved unilaterally or by forcing it ‘bilaterally’ upon Israel, is a recipe for more conflict and bloodshed.

The claim of Israeli occupation of Gaza following its 2005 Disengagement plan promoted by international organisations gives rise to the deep suspicion that Israel will never be able to meet Palestinian demands. Shortly put, the Palestinians will never allow ‘the Occupation’ to end. While a demilitarised state is promoted as a potential solution, in reality, it would be unworkable. A weak Palestinian security force would likely be at the mercy of terrorist-affiliated armed militias, while a powerful security force would eventually threaten Israel. The cases of Costa Rica and Haiti also demonstrate that demilitarisation may be reversed years or decades later. There is no guarantee that a Palestinian state will remain demilitarised in the future.

7 October must not become the Palestinian independence day. Israel’s focus now must be on eradicating Hamas and other terrorist groups. Until Palestinian society undergoes a radical reevaluation of its foundational values and accepts mutual recognition of Jewish national claims, the idea of a Palestinian state must be moot.

[1] ECtHR, Sargsyan v. Azerbaijan, Application no. 40167/06, 16 June 2015, para. 94 and ECtHR, Chiragov and Others v. Armenia