In 2022 book-lovers celebrate the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s masterpiece Ulysses, which tracks the peripatetic wanderings of Leopold Bloom in Dublin on 16 June 1904. Each year on that day ‘Bloomsday’ is celebrated by lovers of the novel. This year, Fathom is delighted to publish an essay by (Israeli-Canadian) Noga Emanuel that looks more closely at the dialectic between antisemitism and Zionism in the novel. Emanuel notes that by the end of his day of wandering Bloom – a ‘non-Jewish’ Jew – recognises he ‘can never be an Irish man, even when he straightforwardly discards Jewish yearnings or joins in the mockery of other Jews. Bloom rightly feels that his Jewishness represents perpetual alienation from “real” Irish people.’ Emanuel concludes that ‘there is a certain quiet heroism in his final realisation that, when all is said and done, his father’s Jewishness is the key to his own humanity.’

Introduction

Joyce’s Ulysses famously takes place over one day, 16 June 1904, as Leopold Bloom wanders through the city of Dublin in a modernised mimicking of the journey taken by the ancient Greek king Odysseus in Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey.[i] Odysseus, the crafty and resourceful architect of Greek victory over Troy, is wending his way home to his beloved wife, son, and city. Between Troy and Ithaca he encounters temptations and obstacles that delay but do not derail his voyage homeward. The exhausted Odysseus has to fight monsters, resist sirens and seductresses, before finally arriving at Ithaca, his homeland. Joyce’s Ulysses is all about wandering, and the immitigable loneliness that comes with it.

Joyce’s choice of the figure of the wandering Jew as the modern-day Odysseus was a deliberate one. Christopher Hitchens maintained that Joyce made Bloom a Jew because the Jewish question was uppermost on his mind. From Dublin to Trieste to Paris, Joyce was labouring on the novel amid a crumbling civilisation. Post-WWI Europe had not resolved the challenges and paradoxes of modernity. 19th century enlightenment values failed to dissolve the intractability of Jewish identity. Like Bloom, the Jew in Europe remained a Jew, voluntarily or involuntarily. ‘In some intuitive manner, Joyce seems to have had the premonition that the Jewish question would be crucial to the 20th century,’ wrote Hitchens.

Homer’s Odysseus was not a great mythical warrior like Achilles. No muse sang of his arête. He was a family man, father and a loving husband who had been dragged into war against his will, and to him eventually befell the task of ending that seemingly un-winnable war, resorting to subterfuge. Likewise, Joyce’s Bloom was not a brawny man strutting about the city, but a pacifist whose fellow-Dubliners consider unmanly and who is subjected to their insults.

The Bloom-Dedalus Friendship

Bloom’s co-hero in the novel is Stephen Dedalus, who walks with him part of the day and returns with him to his home at its end. Bloom has grown to love the troubled and (since that morning) homeless young man and wishes to adopt him. His offers are declined. As Stephen departs Bloom’s home at past two in the morning, readers are left perplexed: will Bloom and Stephen remain friends? James Joyce famously said that he ‘put so many enigmas and puzzles [into Ulysses] that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.’ The question of the Bloom-Dedalus friendship has certainly given rise to many speculations from the critics. Some assume that friendship to be a near-certainty. The more cautious warn against making such hypotheses. For me, this is not one of those ‘enigmas and puzzles’. The turmoil within Bloom is triggered by many life factors and perplexities, among which the dialectic between antisemitism, Jewish identity and Zionism is major but not singular. But if we pay special attention to that dialectic we can see that the friendship will not outlast the night.

Leopold Bloom, Joyce’s Odysseus, is Jewish. Although he was born to a Catholic mother and a Jewish Hungarian convert, and was baptised at birth, so is not a Jew in any formal Jewish or Irish-Catholic sense, he is known throughout Dublin as a Jew and is treated like one, enduring antisemitic jeers and humiliations, the butt of Jew-baiting jokes, wherever he goes. There are explicitly 25 direct mentions of ‘Jews’ in the entire text, and many other implied references, most of them conveying classically crude antisemitic slanders, fewer samples of modern antisemitic conspiracies, and fewer still neutral mentions (six mentions in the final and 18th chapter ‘Penelope’, which is Bloom’s wife Molly’s interior monologue).

When Bloom tries to avow himself a bona fide Irishman, neither his compatriots nor his author allow him to be one. Indeed, one could argue that had Bloom been an Irishman, fully assimilated, no longer Jewish in any formal or cultural sense of that identity, his author would have had no use for him. No, Bloom is still a Jew. Neither the jeering Dubliners, nor Joyce misread his identity. Perhaps most clueless is Bloom, who longs to belong organically to the Irish nation while being literally incapable of wresting himself from his deeply felt Jewish awareness. It takes Stephen’s proverbial slap near the day’s end to clarify this for him.

Those who are attentive to it may discern in Joyce’s Ulysses a dialectical rhythm between antisemitism and Zionism. Just as a neo-Impressionist Pointillist painting becomes comprehensible to the eye when we step back from the tiny dots of colour, if we pull back from Joyce’s dazzling, dancing textual dots of interlacing micro-events and ruminations, we can trace a certain pattern in which explicit antisemitic manifestations cue in Zionist visions and ideas, and Zionist allusions cue in antisemitic tropes. Over the course of the day, the initially modern ‘rational antisemitism’ we encounter in the morning hours transmogrifies into dark medieval hatred, while the Zionist yearning becomes more heavily invested with Jewish emotional premonition. The day is thus bracketed, opening and ending on the same two notes: Antisemitism, Zionism, Zionism, Antisemitism. Bloom is the main protagonist; Stephen, as his companion and interlocutor, acts as a Greek chorus, commenting and clarifying to Bloom and the reader.

Let’s walk through the pertinent episodes on 16 June 1904 and see where it gets us.

The Pleasures of Antisemitism in the Morning

We meet Stephen Dedalus first on the morning of 16 June 1904, engaging in edgy conversation with Mulligan, his Irish roommate and, a little later, with Haines, who Mulligan describes as ‘a ponderous Saxon… Bursting with money and indigestion.’ Stephen is afraid of Haines, who owns a firearm and has nightmares about hunting black panthers.

Later in the chapter, Stephen realises Haines is ‘not all unkind,’ and Haines’ eyes are ‘unhating.’ Indeed, a few moments after Stephen’s realisation, the Englishman reassures him that he does not hate the Irish.

‘We feel in England that we have treated you [the Irish] rather unfairly. It seems history is to blame. [–] Of course I’m a Britisher, Haines’ voice said, and I feel as one. I don’t want to see my country fall into the hands of German jews either. That’s our national problem, I’m afraid, just now.’

Haines blames history for British oppression of the Irish and, apropos of nothing, his mind turns to the Jews, voicing a more urgent national problem, that of the international Jewish conspiracy.

Later that morning, near the end of the second chapter, ‘Nestor’, the proud Unionist Mr. Deasy, headmaster at the school where Stephen is a teacher, expands ghoulishly on Haines’ theme of Jewish power, mixing old and new antisemitic slanders:

‘Mark my words, Mr Dedalus, he said. England is in the hands of the jews. In all the highest places: her finance, her press. And they are the signs of a nation’s decay. Wherever they gather they eat up the nation’s vital strength. I have seen it coming these years. As sure as we are standing here the jew merchants are already at their work of destruction. Old England is dying.[-] They sinned against the light, Mr Deasy said gravely. And you can see the darkness in their eyes. And that is why they are wanderers on the earth to this day.’

Stephen, mainly passive in this exchange, asks Deasy, ‘A merchant … is one who buys cheap and sells dear, jew or gentile, is he not?’

As Stephen walks out, Deasy runs after him, anxious to belabor his point:

‘I just wanted to say, he said. Ireland, they say, has the honour of being the only country which never persecuted the jews. Do you know that? No. And do you know why? [-] Because she never let them in, Mr Deasy said solemnly.[-] She never let them in, he cried again through his laughter … that’s why.’

These early passages – Haines’ reference to Jewish power and Deasy’s incontinent obsession with Jews – signal to the reader that antisemitism is not only well established in Ireland; it is multi-dimensional and thickly ambient in the culture. The venomous statements prompt Leopold Bloom’s appearance in the novel.

8am. Leopold Bloom on the quayside at Jaffa

While Stephen is receiving his early morning education on Jews, we find Bloom about to prepare breakfast for his wife who is still sleeping. Realising he is short of the necessary meat he needs, Bloom walks to the butcher to buy a pork kidney. At the butcher’s, waiting his turn, he picks up a page from a ‘pile of cut sheets’ used for wrapping meat on the butcher’s counter and reads:

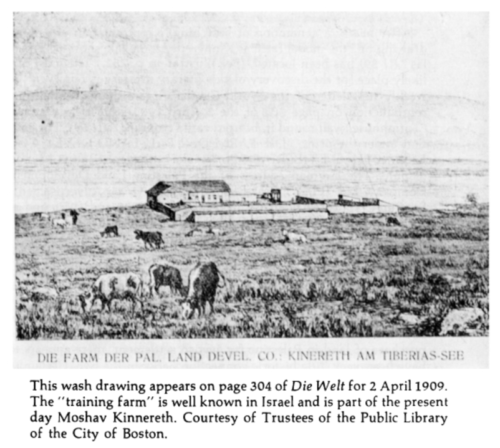

‘.. the model farm at Kinnereth on the lakeshore of Tiberias. Can become ideal winter sanatorium. Moses Montefiore. I thought he was. Farmhouse, wall round it, blurred cattle cropping. He held the page from him: interesting: read it nearer, the title, the blurred cropping cattle, the page rustling.’

The page, containing two advertisements with a common motif and a mention of ‘Moses Montefiore’, confirms for Bloom what he had already guessed, that the Butcher Dlugacz, who reads papers with strong Zionist leanings, must be a Jew.

Bloom’s interior references to Dlugacz are hardly complimentary: ‘ferreteyed porkbutcher .. with blotchy fingers, sausagepink’. A minute later, when the butcher thanks him for his custom, Bloom’s mind continues the animalistic metaphor:

‘A speck of eager fire from foxeyes thanked him. He withdrew his gaze after an instant. No: better not: another time.

— Good morning, he said, moving away.’

Despite Bloom’s interest in the subject of that farm on the shore of Kinnereth and the fleeting spark of mutual recognition between him and Dlugacz, he declines the unspoken invitation to talk about it. We are uncertain why: is Bloom – in his self-perception as an Irishman – reluctant to share a common interest with the Jewish porkbutcher? Is he in a hurry to exit the shop so he can ‘catch up and walk behind’ the ‘nextdoor girl’, a young woman whose ‘vigorous hips’ and ‘strong pair of arms’ are, he lasciviously notes, ‘Pleasant to see first thing in the morning’? Rather than talk to a ham-handed butcher about some ‘model farm at Kinnereth’ he would prefer to ogle the slowly ‘moving hams’ of the young woman, it seems.

Once outside, and with no sign of the girl in sight, Bloom returns his attention to the page he is holding, moving on to the second advertisement:

‘He walked back along Dorset street, reading gravely. Agendath Netaim: planters’ company. To purchase waste sandy tracts from Turkish government and plant with eucalyptus trees. Excellent for shade, fuel and construction. Orangegroves and immense melonfields north of Jaffa. You pay eighty marks and they plant a dunam of land for you with olives, oranges, almonds or citrons. Olives cheaper: oranges need artificial irrigation. Every year you get a sending of the crop. Your name entered for life as owner in the book of the union. Can pay ten down and the balance in yearly instalments. Bleibtreustrasse 34, Berlin, W. 15.’

The ad published by ‘Agendath Netaim’ is a fictional invention composed by Joyce but it was inspired by actual Zionist initiatives for collectively owned agricultural projects to purchase land from the Ottoman government and train Jewish immigrants to become successful farmers.

Bloom’s interest is stirred. We see the natural curiosity of a well-read, relatively broad intellect about a subject that touches intimately upon his own ancestry. Unlikely to respond to the call in the ad, he is nevertheless intrigued: ‘Nothing doing. Still an idea behind it.’ Not for me, he says, but the larger, underlying idea of such initiatives – Zionism – is not to be trifled with.

Bloom casts his imaginary eye on the landscapes the ad’s promised bounties has opened in his mind:

‘… the cattle, blurred in silver heat. Silver-powdered olive trees. Quiet long days: pruning, ripening. [] Oranges in tissue paper packed in crates. Citrons too. [] Crates lined up on the quayside at Jaffa, ticking them off in a book, navvies handling them in soiled dungarees.’

Bloom’s sun-bathed daydream dissipates when ‘A cloud began to cover the sun slowly, wholly. Grey. Far.’ Immediately abandoning the vision of a bustling Jaffa port and its crated oranges, his mind reverts to its more conventional view of that land:

‘A barren land, bare waste. Vulcanic lake, the dead sea: no fish, weedless, sunk deep in the earth. No wind would lift those waves, grey metal, poisonous foggy waters. [] All dead names. A dead sea in a dead land, grey and old. Old now. It bore the oldest, the first race. [] The oldest people. Wandered far away over all the earth, captivity to captivity, multiplying, dying, being born everywhere. It lay there now. Now it could bear no more. Dead: an old woman’s: the grey sunken cunt of the world.’

Bloom’s flesh physically shudders as his thoughts conjure up the ancient land of the Jews as an old woman’s dead and cold womb. ‘Desolation. Grey horror seared his flesh. ‘

Joyce’s spectral metaphor for an unresuscitable ancient nation would reappear no more than three decades later in Primo Levi’s post-Auschwitz lamentation:

Consider if this is a woman

Without hair, without name,

Without the strength to remember,

Empty are her eyes, cold her womb,

Like a frog in winter.

With this chilling image in mind, Bloom folds the page into his pocket, turns into Eccles Street, and hurries homeward.

5pm: The Rage of Pugilistic Antisemitism in the Afternoon

Bloom’s day as he wanders from one place to another, carrying out his list of errands and tasks, is also an exhausting record of the lacerating antisemitic slights he endures with great patience.

At midday, in episode 6 ‘Hades’ Bloom is made to feel excluded by a group of Irish mourners on the way to a funeral. As they spot a locally known Jewish money-lender, they sneer at the man. ‘We have all been there’ intones one of them before, looking askance at Bloom, he corrects himself: ‘Well, nearly all of us.’ Bloom’s hapless attempts to join in the spiteful badinage about the Jew are callously and categorically snubbed.

Episode 12, ‘Cyclops’, takes place in a bar a few hours later, An anonymous narrator reports what happens when a posse of bellicose drunken antisemites, led by an Irish ultra-nationalist known as ‘the citizen’ pester Bloom for being ‘half and half’. Already inwardly wounded, Bloom is now baited explicitly, with a more belligerent version of the earlier exchange. The volume of hatred meted out to Bloom in this scene has reached a crescendo, too overpowering for his habitual and natural docility to ignore.

‘What is your nation if I may ask? says the citizen.’ Bloom’s clear answer, ‘Ireland.. I was born here. Ireland’ is met with silence and a spitball ‘out of [the citizen’s] gullet and, gob’. Bloom qualifies: ‘I belong to a race too … that is hated and persecuted. Also now. This very moment. This very instant. Robbed … plundered. Insulted. Persecuted. Taking what belongs to us by right. At this very moment, says he, putting up his fist, sold by auction in Morocco like slaves or cattle.’‘Are you talking about the new Jerusalem?’ inquires the citizen

Bloom’s expostulation about the miserable state of world Jewry, follows his avowal as an authentic Irishman as well as a Jew. This honest answer gains him – respectively – a spitball and a suspicious watchfulness from the Citizen. The reference to ‘the new Jerusalem’ should alert us to ‘the Citizen’s awareness of the Zionist movement’s efforts to win over the great powers of Europe and the Ottoman Empire to sponsor an autonomous Jewish state in Palestine.[ii] Arguably, the Citizen regards Zionist yearnings as validating the ancient suspicion of Jews as secret and conniving aliens, hence his scornful attitude towards Bloom’s outburst. For the quintessential Irish antisemite, Jews can never have a legitimate claim or a place to exist as themselves. The idea of a Jewish state draws from him as much ire as the Jewish desire for assimilation. For the Citizen, Jews are irredeemably and perpetually ‘strangers in the house’.

To read ‘Cyclops’ and watch Bloom trying to reason with the antisemites is to enter into a surreal universe. Can he really be that naïve? How can he not realise that his rational arguments and pleas for justice and kindliness only serve to whip up hatred towards himself and any kind of Jewish existence? This long episode isa litany of antisemitic slanders, conspiracies and fantasies, culminating in a physical attack on Bloom and a threat by the Citizen to ‘bloody well worth to tear him limb from limb’, to the raucous laughter of all present.

The minutely-written episode, building up to its violent climax, reveals the depths of Joyce’s intimacy with the livid antisemitism within Irish ultra-nationalism.

2am. Bloom recites a Zionist Poem to Stephen Dedalus…

Like Joyce, Bloom was a student of Spinoza. Among the books on his shelves there is a volume of ‘Thoughts from Spinoza (maroon leather).’ Episode 17, ‘Ithaca’, is the most Spinosist in the novel. The penultimate chapter sees Bloom and Stephen arriving at Bloom’s house, nearing the end of Bloom’s Odyssey. The episode is constructed as a series of questions and answers, in a kind of dogged and sometimes merciless computation of all that had been experienced, imagined, done, thought, felt and spent during that day, from the smallest most insignificant detail to the greatest impressions about the place, time and the individuals at the heart of this novel. It could be Joyce experimenting with Spinoza’s attempt in the ‘Ethics’ to organise the manifold human condition within the precision of Euclidean geometry.

From the conversation that Bloom and Stephen engage in, we realise that the day’s cumulative challenges to Bloom’s ethnic identity are still preying on his mind. He draws similarities between the Jews and the Irish as two nations that suffered great defamation and persecution, and are in the process of re-inventing themselves as distinct in language, culture, literary heritage, political aspirations, and revitalised self-esteem. Bloom is animated, almost giddy, with the exuberance that comes from the easy mutual understanding between intellectual equals.

Agreeing that ‘points of contact existed between these languages and between the peoples who spoke them’, Bloom and Stephen each recite a poem to illustrate the dialectic between Jew and Irishman.

‘What anthem did Bloom chant partially in anticipation of that multiple, ethnically irreducible consummation?

Kolod balejwaw pnimah

Nefesch, jehudi, homijah. ‘

The couplet sung by Bloom translates thus ‘As long as within the heart’s depths / Vibrates a Jewish soul’s quintessence’. Bloom does not know the rest of the poem beyond these two lines which he recites in the original (somewhat antiquated) Hebrew. Joyce does not share with the reader Bloom’s ‘periphrastic version of the general text’, but I will: It is Naftali Herz Imber’s 1878 poem ‘Hatikvah’, expressing Jewish aspiration ‘to return to the land of our forefathers’. In 1887 the poem was put to music and adopted as the anthem of the Zionist Movement and, in due time, the State of Israel’s. At the Sixth Zionist Congress at Basel in August 1903, the poem was sung robustly by those favoring the Jewish homeland in Palestine as expressed in the line ‘An eye still gazes toward Zion’.

That Bloom knows about this anthem, can sing part of it, and explain its meaning, a mere 10 months after that event, suggests that the Jewish porkbutcher Dlugacz, who had wrapped the pork-kidney for Bloom that morning, was not the only Jew in the novel with a keen interest in Zionism.

… and Stephen Dedalus reads an antisemitic poem to Leopold Bloom

It’s now Stephen’s turn. He begins:

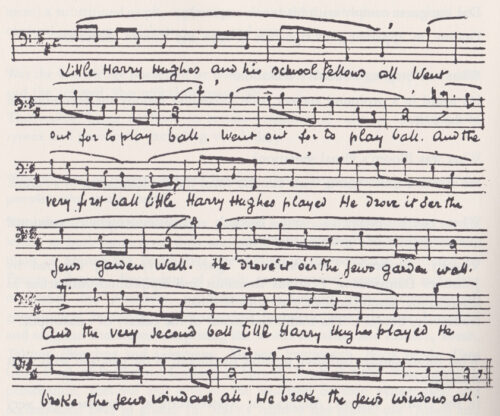

Little Harry Hughes and his schoolfellows all

Went out for to play ball.

And the very first ball little Harry Hughes played

He drove it o’er the jew’s garden wall.

And the very second ball little Harry Hughes played

He broke the jew’s windows all.

Then out there came the jew’s daughter

And she all dressed in green.

‘Come back, come back, you pretty little boy,

And play your ball again.’

‘I can’t come back and I won’t come back

Without my schoolfellows all.

For if my master he did hear

He’d make it a sorry ball.’

She took him by the lilywhite hand

And led him along the hall

Until she led him to a room

Where none could hear him call.

She took a penknife out of her pocket

And cut off his little head.

And now he’ll play his ball no more

For he lies among the dead.

Listening with an expectant smile to the first stanza, Bloom is caught unprepared for what unfolds in the rest of this ghoulishly antisemitic poem. Stephen’s neutral explanation about the poem’s ‘victim predestined’ passively consenting to his own murder, disturbs and saddens Bloom as he ‘weighed the possible evidences for and against ritual murder: the incitations of the hierarchy, the superstition of the populace, the propagation of rumour in continued fraction of veridicity, the envy of opulence, the influence of retaliation, the sporadic reappearance of atavistic delinquency, the mitigating circumstances of fanaticism..’.

Neither Bloom nor reader are offered any plausible explanation why Stephen reciprocated his host’s Jewish anthem about eternal hope with a chilling blood libel. The literary critics too appear to be either incurious or flummoxed by this scene; beyond noting it, they offer little help. It is noteworthy, however, that the dialectic between antisemitism and Zionism earlier indicated in this article is repeated here but in reverse order: Bloom’s Zionist song cues in Stephen’s horrific poem.

Soon after, Bloom offers to embrace Stephen in any way the latter would want: as a lodger in his house (Stephen has been homeless since that morning, remember), as an adopted son, as husband to his daughter Milly, as a son to his wife Molly, who had been bereaved of her own son these eight years. His offers are ‘Promptly, inexplicably, with amicability, gratefully … declined.’

Bloom’s Final Reckoning

We are now drawing to the end of Bloom’s turbulent waking hours. Stephen has departed and Bloom is cogitating on his day as he prepares to go to bed. With the focus of this article in mind, two things stand out, suggesting some kind of denouement.

First, Bloom pulls out from his waistcoat the folded page of the ‘prospectus (illustrated) entitled Agendath Netaim’ he had taken from the butcher that morning, and after examining it superficially, rolls it into a thin cylinder to use as kindle to burn some aromatic incense. The piece of paper is then placed in the basin of the candlestick until it is burned out completely. So .. ‘Nothing doing.’

Second, looking at himself in the mirror, Bloom ruefully observes that ‘From infancy to maturity he had resembled his maternal procreatrix. From maturity to senility he would increasingly resemble his paternal procreator.’ Casting his mind across the infinite number of names, places, ideas, events, biographical experiences, and teachings his Jewish father passed to him, his mind, navigating between Irish geography and millennial Jewish wanderings, Bloom comes to a realisation that there will be no single simple solution to who he is: ‘Assumed by any or known to none. Everyman or Noman.’ There can be no perfect synonymy between how he is viewed and what he is to himself.

Throughout his roamings on 16 June 1904, Leopold Bloom’s attempts to be counted as an Irishman made him an easy target for the city’s mindless cruelty. His excellent but fleeting friendship with Stephen – from which he derives so much pleasure and a sense of worth that comes from being genuinely heard – concludes with a doleful recognition that there will be no father and son relationship in the future. Stephen is predestined to greatness that he, Bloom, will not inspire or share. Putting it more bluntly, Stephen (Joyce’s representative in the novel) is an authentic ethnic Irishman through and through, even when he departs from Ireland for good, while Bloom can never be an Irish man, even when he straightforwardly discards Jewish yearnings or joins antisemites in their mockery of other Jews. Bloom rightly feels that his Jewishness – though he does remind us that he is not formally a Jew – represents perpetual alienation from ‘real’ Irish people. But perhaps there is a certain quiet heroism in his final realisation that, when all is said and done, his father’s Jewishness is the key to his own humanity. More about this in a minute.

Final Thought: The Necessity of ‘Animos effoeminarent’

In the late 17th century, the Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza famously wrote that ‘were it not that the fundamental principles of their religion discourage manliness, I would not hesitate to believe that [the Jews] will one day, given the opportunity – such is the mutability of human affairs – establish once more their independent state.’

For Spinoza, the key to the possibility of Jewish revival as a nation in the Holy land was ‘animos effoeminarent’ – i.e. manliness, courage, affirmative vitality. Already sundered from the Jewish community of Amsterdam, Spinoza was doubtful that the Jews, long depleted of their vigor due to religious customs and diasporic history, would succeed in revitalising their national spirit. However, he thought it remained a viable undertaking under certain circumstances – ‘such is the mutability of human affairs’.

Bloom is invariably perceived as meek and unmanly by his fellow-Dubliners. When he rues the injustice inflicted upon Jews, Bloom is pleading for something that no one around him can understand or respect. The answer he gets is: stand up to it with force, ‘like men’. All this pleading and speaking of universal love as the corrective for the injustice to Jews and Irish alike is deemed ‘unmanly’ and wins him even more violent vituperation. The ‘love’ Bloom prescribes cannot cure antisemitism or gain him one iota of respect from his fellow-Dubliners. But, contra Spinoza, it is not Jewish laws or customs that have depleted Bloom’s spirits but rather his disinclination to accept himself as a Jew. The only time we see him animated is when he responds to the Citizen’s taunts by shaking his fist and speaking for the Jewish people, as a collective.

Hannah Arendt (born in 1906), a younger contemporary of Bloom and Joyce, created a typology of European Jews living in gentile, often antisemitic, societies. The earlier Bloom, who tries to belong to a society in which it is a disgrace to be a Jew, she would have spurned. The later Bloom, who finally discards this self-deceit at past two o’clock in the morning, she would have considered her natural ally. By accepting his alienation from both Jewish and gentile societies, he is rewarded with the honour, honesty and unflinching clarity that make life worth living: ‘Assumed by any or known to none. Everyman or Noman.’

Bloom’s year, let’s remember, is 1904. Joyce is writing this in 1920, as a witness to the gathering storm of bare-knuckled antisemitism in Europe and the glacial progress of Zionism in the international arena. The Holocaust and Jewish Statehood are still in supposition, barely audible thunderclaps of history to be. Bloom is not yet called on to make the more robust choice that Hannah Arendt was required to make, in 1933 Germany – of which Spinoza would have approved – when she said: ‘If one is attacked as a Jew, one must defend oneself as a Jew. Not as a German, not as a world-citizen, not as an upholder of the Rights of Man, or whatever. But: What can I specifically do as a Jew?’

References

[i] Brittanica.com summarises Joyce’s novel thus:

All the action of Ulysses takes place in and immediately around Dublin on a single day (June 16, 1904). The three central characters—Stephen Dedalus (the hero of Joyce’s earlier Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man); Leopold Bloom, a Jewish advertising canvasser; and his wife, Molly—are intended to be modern counterparts of Telemachus,Ulysses (Odysseus), and Penelope, respectively, and the events of the novel loosely parallel the major events in Odysseus’s journey home after the Trojan War.

The book begins at 8:00 in the morning in a Martello tower (a Napoleonic-era defensive structure), where Stephen lives with medical student Buck Mulligan and his English friend Haines. They prepare for the day and head out. After teaching at a boys’ school, Stephen receives his pay from the ignorant and anti-Semitic headmaster, Mr. Deasy, and takes a letter from Deasy that he wants to have published in two newspapers. Afterward Stephen wanders along a beach, lost in thought.

Also that morning, Bloom brings breakfast and the mail to Molly, who remains in bed; her concert tour manager, Blazes Boylan, is to see her at 4:00 that afternoon. Bloom goes to the post office to pick up a letter from a woman with whom he has an illicit correspondence and then to the pharmacist to order lotion for Molly. At 11:00 AM Bloom attends the funeral of Paddy Dignam with Simon Dedalus, Martin Cunningham, and Jack Power.

Bloom goes to a newspaper office to negotiate the placement of an advertisement, which the foreman agrees to as long as it is to run for three months. Bloom leaves to talk with the merchant placing the ad. Stephen arrives with Deasy’s letter, and the editor agrees to publish it. When Bloom returns with an agreement to place the ad for two months, the editor rejects it. Bloom walks through Dublin for a while, stopping to chat with Mrs. Breen, who mentions that Mina Purefoy is in labour. He later has a cheese sandwich and a glass of wine at a pub. On his way to the National Library afterward, he spots Boylan and ducks into the National Museum.

In the National Library, Stephen discusses his theories about Shakespeare and Hamlet with the poet AE, the essayist and librarian John Eglinton, and the librarians Richard Best and Thomas Lyster. Bloom arrives, looking for a copy of an advertisement he had placed, and Buck shows up. Stephen and Buck leave to go to a pub as Bloom also departs.

Simon and Matt Lenehan meet in the bar of the Ormond Hotel, and later Boylan arrives. Leopold had earlier seen Boylan’s car and followed it to the hotel, where he then dines with Richie Goulding. Boylan leaves with Lenehan, on his way to his assignation with Molly. Later, Bloom goes to Barney Kiernan’s boisterous pub, where he is to meet Cunningham in order to help with the Dignam family’s finances. Bloom finds himself being cruelly mocked, largely for his Jewishness. He defends himself, and Cunningham rushes him out of the bar.

After the visit to the Dignam family, Bloom, after a brief dalliance at the beach, goes to the National Maternity Hospital to check in on Mina. He finds Stephen and several of his friends, all somewhat drunk. He joins them, accompanying them when they repair to Burke’s pub. After the bar closes, Stephen and a friend head to Bella Cohen’s brothel. Bloom later finds him there. Stephen, very drunk by now, breaks a chandelier, and, while Bella threatens to call the police, he rushes out and gets into an altercation with a British soldier, who knocks him to the ground. Bloom takes Stephen to a cabman’s shelter for food and talk, and then, long after midnight, the two head for Bloom’s home. There Bloom makes hot cocoa, and they talk. When Bloom suggests that Stephen stay the night, Stephen declines, and Bloom sees him out. Bloom then goes to bed with Molly; he describes his day to her and requests breakfast in bed.

[ii] We may note that the founder of Zionism, Herzl, who had written his vision of the new Jerusalem, ‘The New Old Country’ (Altneuland) died on 3 July 1904, 18 days after Bloom’s Odyssey. Joyce was writing of Bloom’s confrontation with ‘the Citizen’ in 1904 knowing something neither of his characters know: the existence of The Balfour Declaration of 1917.

Brilliant analysis- thank you. In reading this, I noticed a detail I had always missed: the Berlin from which to purchase farmland near Lake Kinneret is “Bleibtreustrasse”, i.e., “Remain Faithful Street”. It’s a real street, but also a reference to Zionism.