Meredith Rothbart is co-founder and CEO of Amal-Tikva. Here, she argues for a new paradigm in Israeli-Palestinian peacebuilding, one in which the relationship between track one dialogue and civil society is much more integrated, and in which NGOs and other actors recognise the error in previously excluding crucial groups from the process.

For many observing from afar, with the current Israel-Gaza war recently passing its 15-month mark, and with no clear end in sight, it is natural to feel a sense of hopelessness about the prospects for peace.

And yet, before abandoning hope, consider the following harsh reality: there has never been a strategic and wholehearted attempt at creating sustainable peaceful relations between Israelis and Palestinians. In other words, we have never really tried to make peace.

While the claim may seem bold, in truth there has never been a comprehensive, cohesive, and strategic effort to change the reality experienced by Israelis and Palestinians from perpetual cycles of violence to a mutually beneficial non-violent reality. It is a mistake, therefore, to conclude that the solutions most experts now agree are most effective in ending conflict have failed in Israel-Palestine. Rather, it is that this best practice has not been implemented. This is what we must change.

At the diplomatic level, there have of course been negotiation attempts with Oslo as the most promising. Unfortunately, the lack of follow-through with regard to the critical implementation left our societies only further devastated by the sense of ‘proof’ that peace is not possible.

On the civil society level, there have been NGOs implementing ‘peace’ programmes for decades, some effectively and some not. There have been activists and protests, also with mixed results.

Civil society actors dedicated to peacebuilding have essentially been waiting for a promising political horizon to give meaning to their efforts, all while top-down negotiations have failed to include civil society, which will be needed to implement key steps toward peacebuilding in the conversation. And then we all wonder why efforts thus far, which have cost so many millions, have yet to succeed in changing reality for the better.

Neither top-down nor grassroots peacemaking can be successful alone. At the same time, we cannot accept failing to create a livable nonviolent reality between Israelis and Palestinians because we are too narrow-minded to see the importance of integrating top-down negotiations with civil society efforts, and vice versa.

Diplomatic negotiations are not enough on their own

Israeli and Palestinian perceptions of the concept of a peace process, as well as support for a potential negotiated resolution to the conflict, were extremely negative even before the 7 October attacks and the subsequent war in Gaza. Leaders from each side blamed the other, claiming they have ‘no partner’, while failing to model partnership themselves. ‘Peace’ became a dirty word within non-liberal groups (read: religious nationalist extremists from both sides).

But this was not always the case.

In the years following the Oslo Accords, which initially enjoyed high support among both Israelis and Palestinians, each society waited eagerly to experience the anticipated gains promised by their respective leaders.

Unfortunately, with almost no civil society engagement in the development or implementation of the Oslo Accords, let alone the compromises the agreement entailed, in retrospect it is not surprising that the agreements collapsed. As Fathom editor Calev Ben Dor wrote, ‘while the Oslo Accords were lauded in Western capitals, many felt uncomfortable with their overtly secular, liberal focus, which didn’t reflect the feelings of most Israelis or Palestinians.’

Reckoning with the failed legacy of Oslo demands assessing how the peace process and top-level peace negotiations at-large have alienated non-liberal populations in both societies. As Rabbi Dr. Daniel Roth, Director at Mosaica, an Israeli NGO advancing mediation and dialogue, said, ‘it’s like politicians are playing a game of protocol ceremony while grassroots are actually being the responsible ones in the field. Sometimes I feel like we should just open a “Prevent Holy War” GoFundMe because official diplomacy is failing to deliver.’

Grassroots peacebuilding is also not enough

Often, after the collapse of an attempted peace process, civil society peacebuilding efforts attempted to fill the vacuum. Unfortunately, many of these efforts also doubled down on the same liberal peacemaking methodologies which had just resulted in the collapse, adopting rights-based or interest-based approaches. In other words, peace efforts at the NGO level were also undermined because they marginalised the traditional majorities whose absence in political processes has been one major contributing factor to their failure.

When a conflict is so deeply ingrained within the values, beliefs, attitudes, and patterns of behaviour of two warring societies, it is important to challenge these elements to their very core. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is unfortunately a flagship example. Eliminating the zero-sum nature would make the conflict feel more resolvable to donors, peacebuilders, religious and political leaders, and society at-large.

Peacebuilding work is commonly misunderstood to represent programmes that focus exclusively on dialogue, bringing people from conflicting sides together to broaden perspectives on ‘the other.’ ‘Contact hypothesis’, as it is known, is very popular, but is not, on its own, enough to change the reality.

At Amal-Tikva, we define ‘peacebuilding’ as working to create a more peaceful reality for Palestinians and Israelis. This reality is defined by less hatred, tension, and violence; increased quality of life; and improved systems for interaction. Peacebuilding cannot merely be preparing civil society for a future political peace agreement, but rather it must include taking concrete steps to make lives better today.

Amal-Tikva meeting with members from multiple NGOs

While peace processes over the last 30 years have continually excluded certain key actors and effectively positioned them as spoilers, it is those same spoilers who have, since the Second Intifada, transformed the status quo altogether – from one of pursuing peace accords to one of entrenched irredentist claims.

Civil society’s unique role

Since the spoilers of the old peace processes have become mainstream influential leaders today (see Hamas, Ben Gvir etc), changing the current reality toward peacebuilding can only happen with them. Only by engaging key actors – even the most extreme actors – and demonstrating that each side’s religious and national aspirations cannot be fully realised through the current violent reality, can peacebuilders reach deeply enough inside their own societies to change the intractable nature of the conflict and move toward a nonviolent political horizon.

This does not mean that every NGO must seek to engage political leadership. Rather, they must map the most influential leaders related to their specific efforts. For instance, the key actors engaged in educational programmes may be specific school systems, the minister of education, or municipal leaders who oversee educational materials. For insider mediators, key actors may include religious leaders of extreme movements, including those at the helm of militant groups.

Breakthroughs for peace in other conflict zones

In Northern Ireland in the mid-1980s, violent attacks were a daily occurrence as tensions boiled over between the Nationalist and Unionist populations. Their respective leaders refused to meet under any circumstance, let alone entertain the notion of a peace agreement that seemed, to most, all but impossible.

The International Fund for Ireland (IFI) helped create the social, economic, and political foundations – what we call ‘social peace’ – upon which a political agreement was secured more than a decade later, by investing in civil society peacebuilding at a far-reaching scale. UK Chief Negotiator Jonathan Powell called IFI ‘the great unsung hero of the peace process,’ and it continues to receive credit for nurturing a culture of peace that has been sustained and strengthened despite periodic and significant political crisis since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

For international investment in Israeli-Palestinian peacebuilding to reach the scale that IFI invested in Northern Ireland, donors would need to invest hundreds of millions of dollars over the next 10 years.

If NGOs, donors, experts, and activists worked strategically and collaboratively to change the zero-sum nature of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, then the conflict would feel more resolvable to the most relevant stakeholders. That is a key first step toward building a just and lasting peace. As we have been watching the work of civil society peacebuilding in the last year and a half, we have never been more certain that this is the correct path.

These dynamics are reflected in “The State of Civil Society Peacebuilding Between Israelis and Palestinians”, a report Amal-Tikva published in late 2024. We collected data from 38 organisations that continue to pursue a better future for Israelis and Palestinians, even as their employees and programme participants are directly affected by the ongoing bloody and traumatising war.

One key finding is that the field of civil society peacebuilding has actually gained capacity, and has become more strategic, since 2020. Quantitatively, we measure this by noting that budgets have increased and funding has become more diverse. Staff sizes have grown since 2020 and remained stable since 7 October 2023, and the start of the current Israel-Gaza war. NGO leadership in peacebuilding has also become more diverse, and team membership has become more equal between Israelis and Palestinians.

Qualitatively, we see that the NGOs are demonstrating resilience and a trend toward becoming more impact-focused, rooted in a sound theory of change. This is evident in their perceptions of the challenges to their work. In our 2020 survey, NGO leaders said their biggest challenges were a lack of funding, an inability to find staff, and difficulty recruiting participants.

Meanwhile, the primary challenges reported in the 2024 survey tend more towards successfully implementing organisational strategy and having the staff capacity to implement it. This shows a shift in the mindset of the NGOs – from blaming external resources for a lack of success to focusing on ensuring their ability to achieve their objectives.

Another finding reveals resilience and strategy in NGOs’ ability to continue operations and programmes effectively during the current crisis. Most programmes across NGOs either continued or were launched during the first six months of the war, and overall, their teams have been stable. Whether staff, volunteers, or lay leaders of NGOs, those deeply affected by the conflict and ongoing war are continuing their efforts within civil society. ‘We believe in ongoing touchpoints; one-time off immersive programmes are insufficient,’ says Hela Lehar, CEO of Tech2Peace. ‘Our community will be at risk if we don’t engage our members at a high pace. On 9 October, we had a Zoom dialogue. We didn’t push anything, we wanted to serve their needs. Then our community came to us and requested in person meetups already at the end of November.’

Such resilience resulted in a real impact on those suffering most from the war. Within the first six months, 40 per cent of 38 NGOs surveyed had delivered aid to people in need, indicating that they had the staff, financial, and strategic capacity to pivot and invest in a new element of their work. More than half (57 percent) of NGOs have been reaching out to new communities, engaging with programme participants and stakeholders beyond their pre-war networks.

Civil society NGOs are not preaching to the choir – because there is no choir

The Israelis and Palestinians involved in civil society peacebuilding efforts are not working at a distance from the war but are instead in the vulnerable position of being directly affected by it. Their pain and suffering cannot be captured in statistics.

Though we cannot quantify the countless ways the war has made life more difficult, we find it important to share how peacebuilding NGOs are part and parcel of the societies they seek to change for the better. We asked respondents how the organisation’s staff members and programme participants were directly affected by the war in the following categories: Bereaved Families, Displacement, Reserve Duty, and Restricted Movement.

Among organisations surveyed, three reported staff members who lost relatives in the war, while 15 reported that programme participants lost family members. Out of 20 programme participants affected across 38 organisations, nine were Israeli and eleven Palestinian. The human toll crosses national lines, reflecting the deeply interconnected nature of these peacebuilding communities.

Eight organisations had staff members displaced from their homes – six Israeli and two Palestinians – while 12 reported displaced programme participants. Nine organisations had staff called to military reserves.

The overwhelming majority of organisations surveyed are binational in both staff and outreach, meaning they employ and serve both Israelis and Palestinians. This means that not only is peacebuilding led by Palestinians and Israelis deeply affected by the conflict, but that they are serving each other through their work even as violence escalates around them. ‘The field of Israeli-Palestinian peacebuilding is actually more resilient than we could have imagined,’ notes Mehra Rimer, co-founder and Executive Director of B8 of Hope. ‘As peace philanthropists closely working with “the field,” we knew it. Yet this survey shows that it was not just our gut feeling but actually a reality. Working and uniting for a shared future is possible.’

While 95 per cent of the of the organisations mapped reported an increase in funds raised in the first year of the war, leaders also noted the need to reach more deeply into their own societies to change societal views of what is possible, either by creating parallel uni-national programmes (those working solely within Israeli or Palestinian society) or going even further and pivoting to entirely separate work within each society on its own. Today’s environment is so violent and polarised that engaging Israelis and Palestinians in dialogue or even basic-level encounters may not be the most effective way to encourage their openness toward a new non-violent construct. There is no inherent value in dialogue for the sake of dialogue, or binational meetings for the sake of binational meetings. Donors and activists alike need to recognise this point. Some examples of uni-national work include religious study on conflict transformation, nonviolent communication training, mediation training, women’s empowerment work, youth civic engagement, and more.

This marks a shift from a model of focusing efforts on trying to maximise the number of Israeli-Palestinian dialogue encounters toward a model which focuses on solving social problems that affect each society uniquely, whether in the presence of the other or not. One example of that is the Rossing Center for Education and Dialogue. ‘We offered schools that we’ve worked with sessions for teachers to process how they’re feeling,’ says its CEO Sarah Bernstein.

Our high school programme trains teachers to conduct conflictual conversations in the classroom, giving them tools to help students express both emotions and opinions. The psychosocial aspect of that work became more important than ever. Feedback showed that teachers were incredibly grateful – they need a support structure, and our programme gives it to them.

Others adopt a diversity of approaches to social change which differ in conflict analysis and in their respective target audiences. The most common approach among surveyed NGOs is education, adopted by 12 NGOs. Other commonly shared approaches include encounters (nine NGOs), political advocacy (nine NGOs), entrepreneurship (five NGOs), and women’s empowerment (five NGOs). And, most importantly, our survey notes a desire to be consistent and strategic through engaging key actors.

Countering scepticism with profound, yet simple, changes

How can we reach populations which, in today’s climate, are increasingly less attracted to the concept of ‘peace?’

To accommodate religious communities, peacebuilding programmes could be more mindful of dietary, holiday, and Sabbath restrictions, or they could offer male-only or female-only groups to address modesty concerns. Simple changes in marketing language, as well as adjusting schedules and locations to meet religious needs or engage community members at different life stages, enables the more conservative groups within society to participate. Similarly, civil society actors dedicated to peacebuilding should lean into their national and/or religious identities.

Uni-national programmes, by design, enable participants from communities generally opposed to peacebuilding to participate. Their engagement can lead to the broader change required within each society that is necessary to support non-violent alternatives in the short term and diplomatic agreements over the long term.

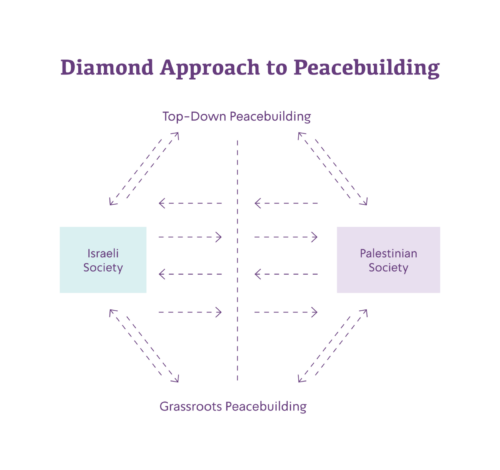

The Diamond Approach

Understanding these factors, Amal-Tikva developed a new framework whose name acknowledges that most peacebuilders come, originally, from one side of the conflict. This is the ‘Diamond Approach.’

These potential Israeli and Palestinian civil society peacebuilders hold the complexity of their own narrative alongside others, and therefore they are the right kind of actors to overcome the ethnocentric scope of each society’s vision. Such an approach shows how the reality on the ground has forced a rethinking of traditional peacebuilding approaches.

Accordingly, the Diamond Approach has four points: the top, representing political/diplomatic ‘top-down’ peacemaking; the bottom, representing grassroots peacebuilding efforts; and the two sides representing each party involved in the conflict. The dotted line in the middle is where the two societies meet, and the people holding that dotted line represent those doing the peacebuilding work. It encourages uni-national engagement, with the intention of sharing observations and developing approaches across national lines that will enable each society to see the development of a new nonviolent construct from within their religious and national aspirations.

Change is possible – when broken down into manageable parts

Change is possible – when broken down into manageable parts

In her book Beyond Violence, Mari Fitzduff, a veteran peacebuilder from Northern Ireland, explains the importance of community relations work aimed at validating cultural diversity as a trust-building measure. ‘Without community relations work,’ she says,

it would have been impossible to address the issues of justice and political choices between the communities. And without community development work, which increased the confidence of communities to address their differences, we would have lacked the addition of new political leaders from the communities who were eventually to help transform the political process and make the [Good Friday] Agreement possible.

The US government has taken the first step toward this path by adopting the Nita Lowey Middle East Partnership for Peace Act of 2020 (MEPPA). To help bring NGOs to that level, resources and strategic efforts need to be well-funded and well-coordinated between donors, activists, NGOs, and academics alike. Money is not enough without the strategy and capacity to create real social change.

Those of us who have worked in the field in a serious capacity have long understood that it was not enough just to bring people together, to run ad-hoc dialogue or trust-building programmes, or to keep operating merely for the sake of operating.

At the same time, we know that though wars are fought by armies through their might and treaties made by political leaders with their power, neither armies nor political leaders alone will bring about lasting peace. Diplomatic efforts at advancing a framework for peace will have to confront the gaping rift between Palestinian and Israeli perceptions of the war, including divergent narratives of what did and did not happen on 7 October, and will need civil society’s help in doing so. Research has proven that peacebuilding programmes change attitudes that conflicting groups hold about each other, establish deeply rooted cooperation, build new feelings of trust, and positively change people’s views about peace.

Each actor must know its role, while coordinating efforts across roles. Just as NGOs cannot end the war, political leaders of narrow ideological camps cannot reach the deepest factions of society to inspire a more nuanced way of thinking about their realities. Just as most journalists do not have the time to dedicate years of deep research to one article, academics do not necessarily have the platforms to translate their research and learning into accessible mediums that reach mass audiences. Peace requires not just an agreement on paper, but momentum toward broad societal change; change that entails internal rehabilitation in both societies, transition from pain and vengefulness to tolerance and compromise, and an eventual relationship-building across national divides.

If each actor knows its role, becomes aware of the roles of the other players, and coordinates strategically toward a shared goal, then change toward a better reality within the context of a new nonviolent construct will be attainable. Even more importantly, change will be desirable among the Israeli and Palestinian societies at-large.