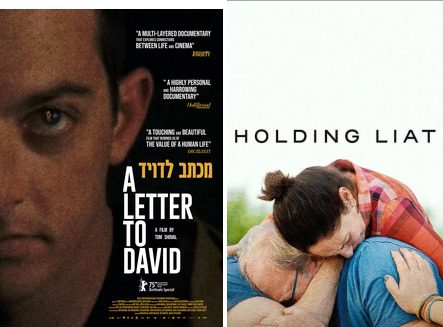

In the wake of 7 October, 2023, Israeli documentary cinema has grappled with an unprecedented challenge: how to bear witness to collective trauma while honouring the intimate, irreducible pain of individual families. Two films – Holding Liat and Letter to David – emerge as contrasting and complementary responses to this crisis. While both centre on families torn apart by the hostage situation in Gaza, they adopt fundamentally different aesthetic strategies.

Holding Liat positions itself at the intersection of the personal and the political, wielding its camera as both a mirror for familial anguish and a weapon against governmental negligence. Letter to David, whose title in Hebrew – Michtav L’David – evokes the book of Psalms and its use as a precious aide in times of anguish, retreats into the enclosed world of the kibbutz, constructing a hall of mirrors where fiction and reality reflect and distort one another in increasingly dizzying ways. Together, these films offer a diptych of Israeli society in crisis – one expansive and accusatory, the other closed and elegiac.

Holding Liat: A Family as Microcosm

Holding Liat, directed by relative Brandon Kramer, follows the Atzili family as they navigate the horrors of uncertainty: their daughter Liat and son-in-law Aviv have been taken hostage; they do not know their fate. What distinguishes this film in the post 7 October media landscape is its refusal to limit itself to the hermetic space of private grief. Instead, it charts the family’s movement through the corridors of power – senators’ offices, congressional hearings, glittering Jewish fundraisers – and in doing so, exposes the political machinery that both sustains and abandons them.

The family becomes a kind of post-7 October “Four Sons,” echoing the four archetypal children presented in the Passover Haggadah, with each member embodying a distinct response to catastrophe that reflects broader ideological currents within Israeli and diaspora Jewish communities. Tal, Liat’s sister, and their mother, Chaya, focus singularly on the safe return of their loved ones, their activism rooted in maternal and sibling urgency rather than political critique. Chaya’s grief is presented as universal, transcending national boundaries – a mother’s pain.

In stark contrast stands Yehuda, Liat’s father, whose trajectory forms the film’s moral and political backbone. Yehuda sees beyond the immediate crisis to the political abyss. His indictment is searing and unsparing: ‘We are being led by crazy people… and the result is death and destruction.’ He asserts that ‘the hostages are not on Bibi’s agenda,’ and his rhetorical question – ‘When has war ever ended well?’ – hangs heavily. He credits his daughter, who is a board member of Women Wage Peace (WWP) and a peace activist, with prescience: ‘Liat, because she’s a lot smarter than I am, understood this way before me.’

The film does not shy away from Yehuda’s discomfort and alienation. At pro-Israel rallies in America, he recoils from the bombastic, right-wing Republican allies wheeled out to a Jewish audience – flag-waving, nationalistic performances that feel as foreign to him as wearing a kippah at the Lubavitch fundraiser they are invited to attend.

His position is paradoxical but deeply Israeli: fierce criticism of the country’s leaders coupled with a deep attachment to the country itself and a refusal to leave.

Tal’s approach offers another perspective: she left Israel for the United States years earlier, believing the country has reached a dead end. She questions whether peace will ever be possible. Everyone has lost someone, she states. ‘How can you make peace in that situation?’ Meanwhile, Neta, Liat and Aviv’s son, voices the raw, unprocessed rage of a generation: ‘Fuck them, they need to die.’ It is the fury of the young, untempered by diplomatic niceties.

What makes Holding Liat unique is its refusal to censor or reconcile these positions. The film holds space for Yehuda’s damning political critique alongside Chaya’s maternal anguish; for Tal’s doubts about the future alongside Neta’s rage at those who murdered his friends and keep his parents’ hostage. In doing so, it captures the fractured landscape of post-October 7th Israeli society, where any remaining internal Jewish or Israeli consensus has been further unravelled.

Letter to David: A Film Within a Film Within a Film

If Holding Liat expands outward into the global political stage, Letter to David spirals inward. Director Tom Shoval’s documentary is built on layers of retrospection and introspection, each layer refracting and distorting the others.

The film’s origin story is itself stranger than fiction. In 2013, Shoval directed Youth, a feature film that starred identical twins David and Eitan Cunio from the Southern Kibbutz of Nir Oz. They weren’t actors, just 20-year-olds with undeniable charisma. The director was drawn to the twins’ extraordinary synchronicity, their intuitive, wordless communication – an almost telepathic bond that gave the film its electric energy. The twins possessed a raw, unpolished quality that made them captivating on screen. Shoval cut his teeth on the documentary, which, like Letter to David, also screened at the Berlinale Festival, and became close to the Cunio family as a result.

With black prescience, Youth centres on a plot in which the twin brothers kidnap a girl and hold her ransom to solve their family’s financial woes. The scene must be shot and reshot, with David and Eitan struggling to embody the aggression needed to authentically convey the situation. ‘Be more violent’ the female actress insists.

‘We were playing with false fire,’ Shoval reflects, in apparent disbelief that the dark fiction they created together could foreshadow their future.

A decade later, in the weeks and months following 7 October, Shoval returns to the Cunio family. David has been taken hostage by Hamas in Gaza along with his younger brother, Ariel. The twin brothers – once actors playing kidnappers – are separated. Eitan remains free while David is held captive in Gaza, a mere handful of miles from their kibbutz.

Letter to David incorporates footage from the 2013 film, behind-the-scenes material, and new interviews with the fractured family. The film-within-a-film structure creates a dizzying mise en abyme where the boundaries between art and life, past and present, collapse entirely.

Unlike Holding Liat, which criss-crosses multiple geographies and social worlds, Letter to David remains largely confined to the kibbutz and its self-sufficient ecosystem. The documentary captures the innocence and idyll of kibbutz life – its freedom, informality, and unbreakable sense of community. Shoval even jokes drily that the name Nir Oz is suggestive of The Land of Oz.

David Cunio is given a camera to record his life during the period of filming Youth, and he films the orange orchards, the potato fields, the wheat crops, the children’s houses. Shoval states ‘I realise you didn’t experience life as threatening, even though your kibbutz sat at the foot of a volcano. Your togetherness protected you, and you didn’t see it.’

When the film does venture outside this reality – to show the Cunio parents in 2024 in their temporary home in Carmei Gat – the landscape is grey, concrete, bleak.

The film’s intimacy and insularity form its strength. It is personal, never overtly political. Even when Shoval interviews Eitan about the events of that dark day in October 2023, with the sounds of strikes in Gaza audible in the distance, there is no direct criticism of the government. This is not a story about policy failures or political betrayals; it is about the unbearable horror one family faces.

Divergent Aesthetics, Complementary Truths

The contrast between these films could hardly be sharper. Holding Liat throws the doors open, moving from their modest kibbutz home to the halls of power, from private grief to public accusation.

With Yehuda’s determination to point a finger and accuse, it insists that the personal is political, that individual suffering cannot be separated from the governmental failures that enabled it. The film’s willingness to air Yehuda’s critique makes it radical – a film not just about loss, but of accountability.

Letter to David, by contrast, circles ever inward around a single family, a single kibbutz, a bond between brothers. The film’s power comes from its restraint and intimacy, its refusal to contextualise or editorialise. It is a powerfully, poignant human story. The story speaks for itself, and the silence around the political circumstances feels like a kind of shell shock.

Holding Liat functions as both testimony and indictment. Its “Four Sons” structure – Yehuda’s critical patriotism, Chaya’s universal grief, Tal’s questioning exile, Neta’s inchoate rage – maps the fractured psyche of a nation and gives voice to the rage and disillusionment that millions of Israelis feel toward their leadership. It captures the sense that the hostages were abandoned for months and years, and that families were left to fend for themselves. By following the family from kibbutz to Capitol Hill, from intimate moments to public spectacles, the film insists that we cannot look away from either the human cost or the political calculus that produced it.

I watched Letter to David twice, the first time in the summer of 2025 while David and Ariel Cunio were still in captivity, fate unknown, and with no hostage release deal or ceasefire in sight. It was so viscerally difficult and distressing that I felt physically winded and needed to stand up from my seat just to breathe and absorb the rest of the documentary. The second time was in researching and writing this article, just weeks after their release in (relatively) good health in November 2025. My sense of personal relief was palpable, but the film still felt as powerful and poignant

Together, these films form a diptych of national trauma. They are documents of a country at war with itself as much as with external enemies, capturing in celluloid what might otherwise be too painful to remember and too dangerous to forget.

—

David and Ariel Cunio were released after 738 days in Hamas captivity on Monday 13th October 2025. David was reunited with his wife, Sharon, and twin daughters, Emma and Yuli, who were released from captivity on day 52. Ariel was reunited with partner Arbel Yehud, released from captivity in January 2025.

Liat was released on day 53 of captivity. Her husband Aviv Atzili was murdered on 7 October and his body recovered from Gaza in June 2025.

Since her release Liat Atzili has spoken at ‘The Time is Now’ a peace-building conference in Israel earlier this year as well as a joint Jewish Palestinian memorial event on Israel’s Yom Hazikaron (Memorial Day).

To express interest in a screening of Letter to David access the film distributor’s website.

The film Holding Liat is available on iplayer. For educational and community-based screenings of the film contact the New Israel Fund UK. Email ella@uknif.org for details.