Izabella Tabarovsky is a Senior Fellow with the Z3 Institute and a fellow with the London Centre for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and ISGAP. Follow her on X @IzaTabaro. Her Fathom essay ‘Soviet Anti-Zionism and Contemporary Left Antisemitism’ is one of our most read.

7 October brought on an explosion of vicious, conspiratorial propaganda about Israel and Zionism. From accusing Israel of perpetrating a genocide, to equating Zionism with Nazism, to whitewashing Hamas’ atrocities (it’s just decolonisation, silly!), to denying empathy to the tortured, murdered and kidnapped Jews: manipulations, fabrications and incitement that have flooded global media over the past nine months have been shocking. But have they been unprecedented? From the technical standpoint, the answer is yes: never before has it been so cheap and easy to pump out lies and antizionist conspiracy theory to so many people simultaneously. In terms of content, however, the current campaign is hardly innovative, borrowing wholesale from the global antizionist propaganda campaigns the USSR ran in the wake of the Six-Day war. The books I’d like to recommend today shed light on that campaign and the geopolitical and cultural context that made it so successful, to help us better understand the current wave of anti-Israel demonisation.

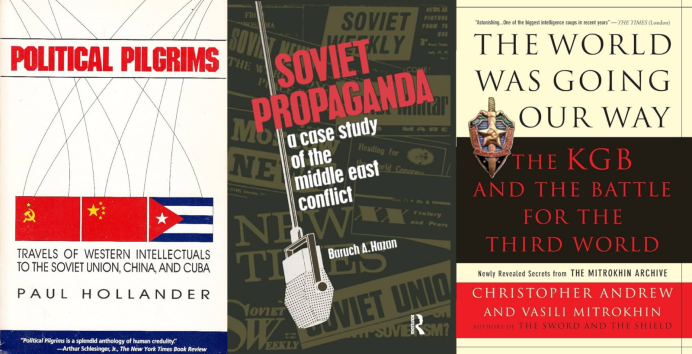

Christopher Andrew and Vasily Mitrokhin: The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World

This book is one of two that Andrew, a historian with the University of Cambridge, and Mitrokhin, a former KGB archivist, co-wrote based on documents the latter smuggled out with him when he defected in the 1990s. Zionism, Israel, and Palestinian terrorism occupy only a small part of the book but what makes the book valuable is that it sets these in the context of the broader Soviet strategy to use the Third World in its proxy war against its Cold War adversary, the United States. Moscow coopted the anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist and anti-racist concerns of these countries, positioning itself as their chief advocate in that struggle and deploying that language in its sweeping anti-Western and anti-American propaganda and disinformation campaigns.

Israel’s victory over the Soviet Arab clients in the Six Day War—unexpected and inexplicable from the Soviet perspective—set off major alarms in Moscow. With antisemitic conspiracy theory firmly part of KGB’s thinking, the agency’s head, Yuri Andropov, elevated Zionism to the rank of USSR’s primary ideological nemesis. Wherever he cast his gaze, Andropov saw the hand of Zionism operating against Soviet interests. With the enemy this omnipresent, the response had to be global as well.

KGB residencies across the world were instructed to increase collection of intelligence on ‘the plans, forms and methods of Zionist subversion’ and work to ‘weaken and divide the Zionist movement.’ Obsessed with the supposedly omnipotent Zionist lobby, the KGB sought to discredit it by forging racist letters in the name of Meir Kahane’s Jewish Defense League and sending them to Black American leaders and heads of Arab missions in New York. Believing that ‘virtually no major negative incidents’ happened in the socialist bloc without Zionist involvement, the KGB blamed Poland’s Solidarity movement on the few Jews within its ranks. At the UN, it helped engineer the passage of the ‘Zionism is racism’ resolution. When the British chief rabbi Immanuel Jakobovits came to the USSR, the agency got eleven ‘highly trained’ KGB agents to talk to him under the guise of ordinary Soviet Jews to convince him that only a small minority among them wanted to emigrate.

In a separate chapter the authors examine Moscow’s relationship with Palestinian terrorist groups. Moscow’s policy was ‘to distance itself from terrorism in public’ while promoting ‘Palestinian terrorist attacks’ in private, they write. KGB had contacts with most Palestinian factions and had agents within both the PLO and the Marxist-Leninist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, where it had recruited the deputy leader and head of foreign operations Wadi Haddad. It trained and armed the groups.

One thing the book makes clear is how much influence the USSR had across the Third World, ‘national-liberation’ movements, and leftist intellectuals. It was this influence that helped Moscow turn its post-1967 antizionist campaign into a global one, which is the subject of my next recommendation.

Baruch A. Hazan, Soviet Propaganda: A Case Study of the Middle East Conflict

Baruch Hazan’s 1976 book provides a detailed look at the themes, techniques and infrastructure of the Soviet anti-Israel campaign up to that point. (In fact, these didn’t change in any fundamental ways in the years that followed.) Hazan’s account helps us grasp the scale and reach of the operation and recognise that while communications technology has improved immeasurably since then, the basic methods of anti-Jewish psyops have largely stayed the same.

In addition to popularising general themes that remain a staple of antizionist campaigning to this day (such as equating Zionism with every evil under the sun, including imperialism, colonialism, racism, Nazism, fascism, terror, apartheid and even antisemitism), Moscow spread sensationalist lies often sourced from Arab media. For example, it accused Israelis of sterilising Arab women or using herbicides to exterminate entire populations of Arab villages. (Variations on these blood libel-like lies frequently pop up on social media today.) The Al-Aqsa blood libel, which remains central to the anti-Israel demonisation today, appeared in Soviet propaganda too, and so did accusations of genocide, with Soviet media harping on the Zionist ‘criminal plan of liquidating the Palestinian people.’ Another theme that appeared in Soviet agitprop and remains in the anti-Israel propagandists’ arsenal to this day is accusing the IDF of intentionally targeting Palestinian children for extermination.

Disseminating lies that evoked powerful emotional responses was a tool Soviet propagandists used deliberately, recognising that no amount of subsequent fact-checking could erase the initial emotional impact. (We’ve seen this dynamic at work in recent months with the Al-Ahli hospital bombing hoax.) Another technique was to accuse Israel of masterminding the very acts of terror that were directed against it—including the murder of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympic Games and the Ma’alot massacre. (The post-7 October Apache helicopter conspiracy theory, claiming that Israeli Air Force intentionally murdered Israelis on that day, is a contemporary version of the same.) All this helped build the image of Israel as inherently and irreparably evil, while denying Israelis any measure of empathy—a fundamental process of dehumanisation that paved the way for today’s college students to assert that ‘Zionists don’t deserve to live.’

Hazan describes Soviet anti-Israel propaganda going into overdrive during major conflicts, drawing on Moscow’s global influence for maximum impact. For example, when Arab states attacked Israel on Yom Kippur of 1973, Moscow announced that it didn’t matter ‘who fired the first shot’ and immediately began to transmit, via its state newswire service TASS, hundreds of denunciations of ‘Israeli aggression,’ coupled with ‘solidarity messages’ hailing the Arab people’s ‘heroic resistance.’ Messages came from heads of non-aligned states and socialist countries, GDR youth associations, the governing party of India, Italian Communist Party, ‘the people of Pakistan,’ Guinea, Malaysia, Mauritania, Upper Volta, Nigeria, Congo, Iran: all of these condemned Israel in unison, in virtually the same language, even as Israel fought for survival.

‘Distortion, falsehood, exaggeration and misrepresentation of facts’ coupled with endless repetition, in multiple languages, tailored to specific audiences across the globe: these were basic tools of the Soviet global anti-Zionist propaganda. Anti-Israel propagandists of today are following down a well-trodden path.

Paul Hollander, Political Pilgrims: Western Intellectuals in Search of the Good Society

Hollander’s book doesn’t touch on Zionism or Israel, but it’s an invaluable read for anyone trying to understand the phenomenon of Western intellectuals standing with Hamas in the wake of October 7. With subtle humor and keen eye for detail, Hollander follows the intellectuals who went to faraway lands (Stalin’s USSR, Cuba, Vietnam, Nicaragua, North Korea) in search of utopia—and found it. The regimes they visited knew exactly what to give them to fulfil their fantasies (flattery was an important tool, among others)—and turn them into their mouthpieces.

Why did so many writers, thinkers, academics choose to disengage their primarily professional skill—critical thinking—when faced with ‘repressive and mendacious totalitarian systems and movements’? Why were they drawn to them in the first place? How did these self-described ‘humanists’ and ‘humanitarians’ succeed at overlooking and excusing the ‘repression, corruption, social injustice’ and ‘organized lying’ staring them in the face? One factor Hollander points to in answering these questions is the unexamined legacy of the 1960s, with its ‘revolutionary romanticism’ and feelings of ‘alienation and estrangement’ from ‘American society’ and ‘its major values and institutions.’ There were, of course, also plenty of personal interests and political agendas involved. The real citizens of these countries—their actual struggles, their longing for dignity and freedom—were irrelevant to this enlightened bunch, who had domestic friends and foes to impress, social ladders to climb, and new op-eds and books to publish and promote.

In the preface to the 1997 edition, Hollander observes that while many had come to acknowledge intellectuals’ past ‘propensity’ for misjudging ‘societies which claimed to be socialist,’ this tendency was by no means a matter of the past: the intellectuals of the late 1990s, he wrote, remained just as susceptible ‘to the claims of certain countries and their political systems.’ This remains astoundingly true today—and possibly has gotten even worse. Not only do today’s intellectuals continue to espouse variations on the manifestly failed Marxist doctrine: they’ve also become an easy mark for Islamist regimes and movements, which skillfully manipulate the latest academic and progressive jargon to get these ‘thought leaders’ to do their bidding: namely, to help destroy a country millions of Jews call home, while claiming, Soviet propaganda-style, that they are only being antizionist and not at all antisemitic.