During the medieval epoch, Christian antisemitism spread the libel that Jews engaged in the ritual murder of non-Jews, supposedly mutilating the bodies and draining the blood of their victims for making Passover bread (also known as “blood libels”). Countless antisemitic pogroms were inspired by this myth. David Gurevich’s shocking account of a contemporary blood libel – the case of Saint Philoumenos, supposedly ‘ritualistically’ murdered by ‘Zionists’ in 1979 and canonised by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem in 2009 – is an important reminder that this poisonous libel is alive today.

St. Philoumenos and Modern Ritual Murder Tale in Nablus Church

A few years ago, a colleague from the UK asked my advice regarding a disturbing story. He showed me a newsletter sent by the Irish Congress of Trade Unions to its subscribers. The publication constituted a report on a solidarity visit of the Northern Ireland Public Service Alliance (NIPSA) to the Palestinian Authority’s territories and Jerusalem. One of the sites mentioned in their report was Jacob’s Well Church in Nablus, an Orthodox Christian sanctuary, which serves both locals and pilgrims. The Irish mission described a peculiar relic in the church:

The church is spectacular with exquisite iconography. I noticed it had a tomb for a martyr—Archimandrite Philoumenos Hasapis. I asked which century he had been martyred in. ‘This one’ was the short answer. He had been murdered with an axe in a ‘ritualistic’ manner on 29 November 1979 by Zionist settlers who wanted to cleanse the area of any trace of Christianity. Murdered whilst performing vespers, his eyes were plucked out and three of his fingers were cut off – the ones with which he made the sign of the Cross. The attacker was believed to be an American. He was not arrested but merely deported back to America.

I immediately felt that something was very wrong about this report. I was not surprised by a biased account from a group defined as a Palestinian-solidarity mission. However, the story of a helpless Christian victim, who was ritually tortured to death by Zionist Jews in the West Bank, evoked more severe concerns.

Almost at the same time, I received an inquiry from a group of Russian Orthodox pilgrims who asked my help with a visit to Jacob’s Well. The pilgrims planned to worship the relics of St. Philoumenos, the same tomb seen by the Irish mission. I checked in the official records and found that the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem sanctified Philoumenos in 2009. A few years earlier, Philoumenos’ body was exhumed from his grave in Jerusalem; the body was claimed to be uncorrupted—typical phenomenon for saints—and later was moved to the renovated Jacob’s Well church in Nablus. The canonisation was adopted in the Russian Moscow Orthodox Patriarchate and in a few other Orthodox churches. The ‘ritualistically-murdered’ martyr, thus, became an officially recognised saint.

Research on the Internet exposed many instances of the same popular narrative that surfaced apparently since 1979. The description is found in church-affiliated sources as well as in general orientation sources. The accounts deviate around certain details, albeit preserving a similar main outline: There was allegedly a group of local ‘fanatical’ Jews, or ‘Zionists’, who wished to cleanse Jacob’s Well of Christians. After threatening Philoumenos, who served as the Archimandrite (head of the monastery), those Jews secretly broke into the monastery. The sources emphasise that the event took place late at the evening, during a heavy rain outside. As to what happened next, I would like to quote OrthodoxWiki, a semi-open Internet encyclopedia of Orthodox Christianity, which quoted the cardinal details on which many accounts agree:

They burst into the monastery and with a hatchet butchered Archimandrite Philoumenos in the form of a cross. With one vertical stroke they clove his face, with another horizontal stroke they cut his cheeks as far as his ears. His eyes were plucked out. The fingers of his right hand were cut into pieces and its thumb was hacked off. These were the fingers with which he made the sign of the Cross. The murderers were not content with the butchering of the innocent monk, but proceeded to desecrate the church as well. A crucifix was destroyed, the sacred vessels were scattered and defiled, and the church was in general subjected to sacrilege of the most appalling type.

The narratives blame the Israeli authorities for covering up the murder. To emphasise the ‘ritualistic’ nature of the event, some sources even added that the body of the monk was confiscated by the Israelis, and it was handed back to the Orthodox church only after several days. In other words, nobody knows what the Israelis did with the body.

Blood Libels

These accounts of what happened at Jacob’s Well take us back into a dark chapter of the history of medieval Europe—the ritual murder accusations and blood libels. Rumours about conspiring Jews capturing a Christian victim, usually a helpless child, to perform religious rites involving torture and the use of victim’s body parts (and the extraction of blood) resulted in the massacre of many Jewish communities in Europe. The first accusation of this type relates to Norwich in 1144. A body of a child named William was discovered in the woods. A Benedictine monk, Thomas of Monmouth, who arrived to Norwich a few years later, was the person behind institutionalising the new cult based on these common rumours accusing Jews.[i] In his The Life and Passion of William of Norwich, he unfolds the circumstances of William’s death and his extensive miracles. Thomas depicted Jews as pure evil who attack Christianity itself. Shortly, William’s burial was moved into the cathedral and he was acclaimed as a saint. Prior to William’s veneration, Norwich was religious centre which did not possess its own saint. The local church mechanism had everything to gain from the new cult – pilgrims, donations, status and influence.

The numerous libellous ritual murder accusations in the next century led to waves of hatred that are (at least, partially) responsible for the expulsion of Jews from England in 1290. Soon, the ritual murder cases emerged in the continent. More details were added as the centuries passed. The most prominent motif was that Jews require Christian blood for baking the Passover matzo bread (i.e., blood libels).

To the Eastern Orthodox realm, the blood libels arrived a few centuries later. They still surfaced around even in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Probably, the most famous chapter in the modern era was written in Czarist Russia with the Beilis Trial in 1913.

One might assume that in the 21st century humanity would have left the old venomous superstition behind. Nevertheless, the texts about Jacob’s Well were quite conclusive. The account of Philoumenos’ tragic martyrdom, the torture by ‘fanatical Jews’, and, furthermore, Philoumenos’ post-mortum miracles, leading to his glorification as a saint, all resonated with the medieval accusations.

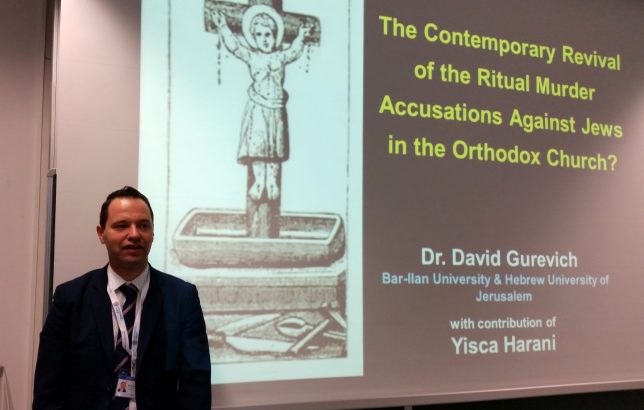

Fig 1: Drawing in the church of Machairas Monastery, Cyprus. 2006. Photograph by the author.

In 2016, I made a professional visit to Cyprus. Philoumenos was born in Cyprus, so I was exploring how he is venerated in his homeland. In the pilgrimage church of the famous Machairas Monastery in Troodos Mountains, I witnessed a painting which depicts Philomenos’ martyrdom—the Christian monk is seen being assaulted by man, who is presented as an Ultra-Orthodox Jew wearing a typical hat, has payot, and a long beard (Fig. 1). Philoumenos was born in a remote small village called Orounta. Visiting the village, I discovered a recently established roadside shrine with a public prayer area (Fig. 2). Three large icons are placed on its wall: St. Nikolaus, St. Luke, and in the middle – the image of St. Philoumenos. Pilgrims frequent the shrine and leave candles and religious artefacts. Shortly after Philoumenos’ canonisation, nuns in the Orounta’s monastery published his hagiography – a comprehensive book which elaborates the saint’s life story, death and the miracle-doings. The book tells about various miracles performed by St. Philoumenos before and after his death. One of the miracles is saving Jacob’s Well church from shells of the ‘Jewish tanks’ who attempted to storm the church in 2005 but were stopped by his intervention.

Fig 2: Road shrine in Orounta, Cyprus. 2006. Photograph by the author.

How Was Philoumenos’ Ritual Murder Narrative Constructed?

So what did really happen in Jacob’s Well on the night of 29 November 1979?

In the last few years, my research partner Yisca Harani and I conducted comprehensive research to answer this question. We checked the police investigation files. We analysed the local press reports since 1979. We interviewed church officials. Yisca visited the site in the Palestinian Authority, and I travelled to Cyprus. Not surprisingly, the facts we established reject the popular narrative. Today we know how the myth was constructed, stage after stage.

The Israeli police started an investigation immediately after the murder. The murderer was caught in 1982. He was a serial-killer, who murdered several people around the country, Jews and non-Jews alike. He was acting alone and lived in Tel-Aviv, far away from Nablus. The murderer was mentally ill. In the investigation protocol, he described hallucinations as well as ‘voices’ that directed him in committing his criminal acts. He was hospitalised in a psychiatric institute by the decree of the Court.

The findings from the crime scene and photographs we consulted in the police investigation file dismiss completely any ‘ritualistic’ nature of his criminal act. The murderer threw a stolen hand-grenade into the church. It caused significant devastation inside. After the monk ran out, the murderer surprised him with an axe causing his tragic death. There were no cross-form hits on the body, victim’s eyes were not plucked out, and, in fact, the murderer sneaked out quickly without delay. Philoumenos lost a single finger of each hand when he tried to protect his face from an axe hit; these were not the fingers which he would use in making the sign of the Cross.

What happened to the body? The body was submitted by the police to a forensic examination. After the examination, the body was returned to the community and brought to its resting place.

Newspapers confirm that rumours about Philoumenos’ death were present shortly after the tragic night in 1979. The ‘ritual murder’ theme accusing Jews suited the cultural prejudices that are still not uncommon amongst the Orthodox believers. The two and half years until the murderer was captured were fertile soil for the growth of this narrative. In 1989, an American monk Yeghia Yenovkian, who claims he knew Philoumenos in his life, composed an obituary marking a decade since Philoumenos’ death. This obituary, published in the periodical Orthodox America, contained the narrative which had been told in the oral form. Soon his essay became the basis for countless publications on Philoumenos’ martyrdom worldwide. This process intensified after the official canonisation in 2009. For instance, in 2012 the Russian Orthodox Church TV channel (Soyuz TV) broadcasted a dedicated show on Philoumenos martyrdom, along which the interviewer wondered ‘what did cause this bright spark of Judaism’s fanaticism particularly in this time?’ and was answered that it happens occasionally and that ‘this bonfire periodically smoulders’.

To understand the framing of the narrative and how its target audience reacts to it, we may refer to the epilogue added to Philoumenos’ martyrdom story by a Belorussian Orthodox website ‘Odigitria’ (translated by the present author). Note the use of the antisemitic derogatory term ‘Zhids’ (Жиды) for Jews.

We remind that the Russian Orthodox Church has two saints, venerated as ‘martyred by the Zhids’: the monk martyr Evstratiy of Kiev-Pechersk and the infant Gabriel of Belostok. The martyr Evstratiy lived in the eleventh century in Kiev. When in 1096 the Cumans attacked and ravaged Pechersky Monastery in Kiev, exterminating many of the monks, the monk Evstratiy was captured, and with thirty monastic workers and twenty habitants of Kiev was sold into slavery to a Jew, who crucified him on a cross. The holy infant Gabriel was ritually murdered by Jews on 20 April 1690. His body side was pierced to discharge the blood, then the infant martyr was crucified.

In this context, we should remember that contrary to the Catholic church, the Orthodox churches have never abolished the veneration of past sanctified ‘victims’ of Jewish ‘ritual murders’. In the course of the general return to religion in the post-Soviet Orthodox states, more of the declined cults were revived. A well-documented example is the recent restoration of the cult of St. Gabriel of Białystok, who is mentioned in the above-presented quote. His relics were translated from Belarus to Bialystok in 1992. The Patriarch of Russia, Kirill, worshiped Gabriel’s relics during his visit to Bialystok in 2012. The Patriach emphasised his appreciation to the local Orthodox community who cherish this Holy Site in the mostly Catholic Poland. Moreover, in 2017, the Russian Orthodox Church established an official committee of inquiry into whether the last Czar was a victim of ritual murder by Jews.

Why do such events still occur in the 21st century? The answer can be found through an in-depth analysis of St. Philoumenos’s case.

Antisemitism as a Tool

The new cult of St. Philoumenos is not solely a product of antisemitic trends nor the geo-political situation in the West Bank. Similarly to the medieval blood libels, material interests contributed to the myth’s distribution. The number of pilgrims to Jacob’s Well increased since the body was moved there. In early 2000, the Palestinian Authority gave its permission to expand the church (which helps to deliver the ‘right’ message, of course). On the saint’s day, 29 November, the church is always packed with worshipers and clergy who travel long distances to attend its ceremonies.[ii] The Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem personally conducts the service. All year around, pilgrims to Jacob’s Well are handed with an information brochure describing the ritual murder performed by ‘fanatical Jews’. The present custodian of the church often shows foreign visitors a tomb that he has already prepared for himself anticipating his future martyrdom in the next assault by the Jewish settlers.

The canonisation of the Cypriot monk indeed played a purpose in strengthening the ties between Jerusalem’s Greek Orthodox Patriarchate and the Cypriot Orthodox Church. In May 2014, a new church was inaugurated at the exarchy of the Jerusalem’s Patriarchate in Nicosia, the capital of Cyprus. The new church was dedicated to Jesus’ Ascension and St. Philoumenos. It is worth noting that the exarchy was re-established after it was shut down following the Turkish invasion of 1974.

Blackwell and the Blood Libel

However, the most alarming development is the protrusion of this popular narrative into academic literature. We found several instances in which notable authors and publisher failed to acknowledge the libellous motifs. Thus, the myth became a ‘well-researched’ truth. For example, Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity (Oxford, 1999) states that ‘Philoumenos was murdered by Zionist extremists determined to remove Christians entirely from this sacred Jewish site’.[iii] We notified the publisher of the error via one of the dictionary’s editors, but Blackwell refused to modify the online version, nor add an explanatory note.

More recently, Rupert Shortt ‘s book Christianophobia: A Faith under Attack (Grand Rapids, MI, 2013) presents the ritual murder narrative as an authentic description of the 1979 events:

Settlers are violent towards Christians and others from time to time. … in November 1979, as yet unidentified fanatics murdered Fr Philoumenos Hasapis, an Orthodox monk, at St Photini’s Monastery beside Jacob’s Well at Nablus. … The killers had already warned Fr Philoumenos to remove Christian symbols from the well, claiming that their presence made it impossible for Jews to pray there. When he refused, they gouged his eyes out and hacked off the fingers of this right hand—the one he used to make the sign of the cross—before ending his life. The current custodian, a veteran of several attacks already, has prepared his tomb for what he senses may be a sudden death.[iv]

The importance of these academic works is that they are generally regarded as credible sources. Readers who seek facts might consume classical antisemitic myths without being aware that the authors failed to challenge the narrative.

Metropolitan Neophytos of Morphou

Back to Cyprus. Our research encountered a person, who might be the ‘living spirit’ behind the extensive veneration of the new martyr. Metropolitan Neophytos of Morphou pushed for writing the hagiography of Philoumenos. Due to the fact that Orounta is located in his ecclesiastical district, the Metropolitan indeed has something to do with the establishment of the new road shrine. Metropolitan Neophytos does not hesitate to use the ritual murder narrative, enhanced with various antisemitic ideas, in his public sermons. In one of his speeches after describing how Philoumenos was murdered by Jews, the bishop delivered a polemic against globalisation and Zionism. He links the martyrdom to what he perceives to be its contemporary context —

All these and even more are contained in the policy of the ‘New Order of Things’, [v] which we mentioned before, that constitutes the global government that is going to control with secret money all the population economically, politically, and socially. There are many researchers that see behind all these the ‘Zionism’, which prepares slowly and steadily the ground for claiming the worshiping of a false God, the Antichrist![vi]

The interest of Neophytos in evoking antisemitic speech seems to have a practical reason. With the Turkish occupation of northern Cyprus in 1974, the Metropolitan of Morphou lost most of his district’s territory. The Metropolinate fled to a non-significant location outside the Turkish territory. Neophytos is a Metropolitan bishop without a diocese and, as said by scholars of church history, ‘Whenever Christianity encountered a frontier, it had a need of martyrs.’[vii] In our case, there is a martyr-saint, a story which mobilises feelings of national pride among believers by blamingthe Jews. Antisemitism is just a tool.

Further Reading

David Gurevich and Yisca Harani, ‘From the Christian Antisemitism to the New Antisemitism: The Case of Philoumenos of Jacob’s Well’, Pp. 139–169 in Antisemitism in Comparative Perspective, vol. 3, ed Charles Asher Small (New York, 2018)

David Gurevich and Yisca Harani, ‘Philoumenos of Jacob’s Well: The Birth of a Contemporary Ritual Murder Narrative’, Israel Studies 21 (2017): 26–54, DOI: 10.2979/israelstudies.22.2.02.

References

[i] On William’s of Norwich history, see the introduction by Miri Rubin to the new Penguin Classics translation: Thomas of Monmouth, The Life and Passion of William of Norwich, ed. Miri Rubin (London, 2014)

[ii] The date 16 November, which is found in some sources as St. Philoumenos of Jacob’s Well day, is observed according to the Julian calendar.

[iii] Fani Balamoti, ‘Philoumenos’ in Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity, eds. Ken Parry, David J. Melling, Dimitry Brady, Sidney H. Griffith and John F. Healey (Oxford, 1999), 380-1.

[iv] Rupert Shortt, Christianophobia: A Faith under Attack (Grand Rapids, MI, 2013), 227.

[v] “Νέας Τάξης Πραγμάτων”. In this context, the meaning of is “New World Order”.

[vi] Translated by Y. Harani and D. Gurevich.

[vii] Donald Weinstein and Rudolph M. Bell, Saints and Society: The Two Worlds of Western Christendom, 1000-1700 (Chicago, 1982), p. 160.

Thank you for mentioning my grandfathers name