S. Yizhar is often called the founding father of Israeli literature and Amos Oz was for many the ‘last best voice’ – the words are Jonathan Freedland’s – of the hopes cherished at Israel’s founding. In this typically lyrical review, Liam Hoare looks back at the novels and stories about the Mandate years left to us by both novelists, paying particular attention to Yizhar’s Preliminaries and Oz’s Hill of Evil Counsel.

In September 1916, between the ratification of the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the publication of the Balfour Declaration, Yizhar Smilansky was born in Rehovot. In the time before the Mandate, what is today a hub of scientific and agricultural research was but a moshava, a village set amidst citrus groves and vineyards. His childhood would be shaped by the Mandate, by an age of Hebrew pioneerism and Jewish-Arab conflict. And what did he, the writer known to the world as S. Yizhar, remember of those earliest days? The colour orange and the spine of the hills, he records in his semi-autographical novel, Preliminaries (1992): movement, curiosity, discovery—and pain.

The literary critic Dan Miron, author of the introductory essay to Nicholas de Lange’s English translation of Preliminaries, argues Yizhar is ‘universally acknowledged as both the founding father of Israeli literature as a whole and as its chief master of prose fiction.’ His early novellas like On the Edge of the Negev (1945) and The Wood on the Hill (1947) ‘focused on the community of pioneers and soldiers that had laid the foundations for a new Zionist society,’ the world in which he was raised. Hirbet Hiz’ah (1949), a literary sensation that tells of the expulsion by Israeli soldiers of Palestinians from their village, and his landmark two-volume work Days of Ziklag (1958) about a company of Israeli soldiers and their six-day attempt to defend their hilltop position from an Egyptian armoured attack in the summer of 1948 are landmarks of Israeli literature.

At his most prolific in the years 1938 to 1958, in his novels Yizhar chronicled the founding of the Jewish state. But by the time of the Six-Day War, he had largely withdrawn from public life, having also retired from the Knesset of which he was a member from 1949 to 1967 (first on the Mapai ticket and then as part of David Ben-Gurion’s breakaway Rafi faction). Though he continued to write academic essays on literary theory in the years thereafter from his perches at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv University, the publication of Preliminaries in 1992 very much came as a ‘literary surprise,’ Miron writes. It was nothing less than ‘a new beginning in the author’s long artistic career,’ the first shot announcing a second literary life in which Yizhar published five new works of fiction in six years.

The five parts of Preliminaries are told in a luxurious, lyrical prose style—the child’s naïve, elementary outlook upon the world melding with the author’s sophisticated retrospection—and unfold like the stations of Zionism in the time of the Mandate. Yizhar places himself and his family at the centre of the Zionist story. As his father tilled the soil on their moshava, Yizhar believes he was ‘actually sitting here inside a theatre’ in which ‘the greatest show on earth is being performed, the spectacle of the birth of the new Jew in the new Land, a show whose main point is the Jew working the land as a free man… The curtain is going up and the thrilling show is about to begin.’

The moshava in Preliminaries is a hermetic environment, removed from the purview of a higher authority save for when Turkish or British troops pass through, ‘tramping and trampling every good plot of land’ under foot. With this isolation comes a certain amount of freedom and one feels in the opening pages of Preliminaries the sense of limitless potential inherent in the Zionist pioneer spirit. ‘Here he is,’ Yizhar writes of his father, ‘taking his destiny in his own hands, and proving that there is no poor land or bad climate or unpropitious conditions in the Land.’

Yizhar’s father was a peasant by day and a writer for socialist Zionist newspapers and journals by night—the sort of man who arrived in Palestine with the Bible in one hand and Tolstoy in the other, an adherent of Aharon David Gordon, committed to the building of a Jewish state through manual labour and agricultural settlement. Yizhar recalls him, somewhat romantically:

…always with a hoe, always with a pruning-hook, and late at night at any old table writing till deep in the night, when the black sky outside became huge and open to man and everything was so open before him.

Of course, the primitive nature of pioneer life in Mandatory Palestine also brought with it tremendous risk and danger: that the land would not produce all that the early Zionists hoped it would; that something as simple as a wasp sting could lead to disaster in a rural environment where a hospital was not within easy reach; and, that though the pioneers were a people without a land, the land was not in fact without a people. It is for these reasons that Preliminaries is shot through not only with hope but fear, a child’s fear, especially in the novel’s second act, which deals with one of the Mandate’s darkest hours: the Jaffa riots of May 1921.

‘There is unease. On every side unease. You can feel it. People crowded together all the time. Not talking aloud. A shadow over everything, it’s unclear what, just a shadow over everything. And unease.’ Families gather apprehensively in the courtyards of their apartment complexes in Jaffa’s Jewish neighbourhoods and enclaves, worrying, wondering, listening. ‘A rumour is going around now. Someone who has just entered through the wicket gate that was opened and immediately closed behind him. They listen and their faces change. They listen and fall silent. The corners of their mounts turn down. They do not know what they can do. They listen and seem not to understand.’ Jaffa’s alleyways, Yizhar writes, smelt of fear.

From the perspective of the Jews of Jaffa, the British were nowhere to be found. It is as if, for Yizhar, ‘the English government had not made up its mind yet.’ It would have been enough, he thinks, ‘for a single British policeman to fire in the air and the whole crowd’ of rioters ‘would have stopped,’ but the Mandatory authorities, he writes, did not know what they wanted. 1921 made it clear to Jaffa’s Jews ‘how vulnerable we all are here and how, not to mince words, foreign we really are, and how unwanted.’ Yizhar articulates the prevailing view of the British at the time as follows:

You’ll see that they [the British] will make no distinction between the Arabs and the Jews, and they’ll treat the killers and the killed, the robbers and the robbed all alike, the attacks and defenders. They’ll haul all of us before the judge together like so many thieves.

This was, indeed, the original sin of the British Mandate. Though they were the original authors of the documents that called for ‘the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people’ and the protection of ‘the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine,’ the British never could quite decide whether it was obligated to do one, the other, or both. In the end, Britain did as it always did: divided and ruled, and then cut and ran, leaving the two sides at each other’s mercy.

Yizhar’s writing on the Jaffa riots is incredibly evocative, full of dread, anger, and peril, his father breaking down as he attempts to find the words to explain that the great Hebrew-language author Yosef Haim Brenner had become a victim of the riots too. But his interpretation of events is also complex and complicated, for with the benefit of hindsight and (at the time of publication) 44 years of statehood, Yizhar views these events through the lens of the Zionist enterprise’s entire history, aspects both light and dark. It is this that makes Preliminaries above all a book about the author’s own disappointment and disillusionment with how Israel turned out once the Mandate came to an end.

By the time he wrote Preliminaries, Yizhar had come to believe that pre-state Zionism simply had not accounted for the Arabs of Palestine. ‘They were never there,’ he writes, ‘in any place or in any argument, in any considerations and certainly not in any songs, they simply did not exist.’ Jews and Arabs had coexisted for a time in Jaffa, as they had in and around Rehovot and other moshavot, but ‘even when nothing happened between [us], all the time something was happening that they tried to hide and not tell the truth about and not to admit that something was not turning out right. Wasn’t this our place? Wasn’t it their place? Were we intruders? Were they intruders?’:

There are two tribes, two nations, two peoples, confronting each other here, and it’s either us or them, and there will never be calm here, there will never be peace, they can’t stand each other, they can’t tolerate each other, they can’t put up with each other, there’s only a thin skin barely covering the mouth of the raging volcano. Go, the earth cries here, get out of here shouts the place, go away, scream the streets, off with you, screech the alleys, away with the lot of you, and Allahu akbar.

With dreams comes the possibility they will remain unfulfilled. Yizhar mourns the domestication or urbanisation of Zionism over the course of the Mandate as manifest in his father’s transformation from rugged pioneer and redeemer of the land, to someone living in Tel Aviv and working for the municipality—someone who ‘goes to work each morning, taking the wicker basket with his lunch wrapped in newspaper and his flask of lukewarm tea, and in the evening he comes home, he reads the paper, and he doesn’t sigh, sometimes he even smiles a twisted smile, at the boy: And that’s the way it is.’

The State of Israel did not become, as those who arrived in Palestine armed with Tolstoy and the Bible like A.D. Gordon and Yizhar’s father had envisaged, a loose federation of small, self-sustaining farming communities whose inhabitants would establish a spiritual connection to the land through physical labour. Gordon believed, Amos Oz has written, ‘in the gradual improvement of human nature through a purification that must come through intimacy between individuals, through a renewal of links with the old elements: the soil, the cycle of the season, tilling the soil, “mother nature,” inner rest.’

The founding of a nation-state and Gordon’s ironic view of the nation itself were two horses pulling in opposite directions and his movement, Hapoel Hatzair, of which Yizhar’s father was a part, had been subsumed into the Mapai by 1930. In time the coastal plain would become a megalopolis and moshavot like Rehovot flourishing cities. The closing pages of Preliminaries thus make for an ode to that which was lost and that which never became: ‘Suddenly he knows that soon none of this will remain,’ he writes of the vineyards and orange groves. It is a coda mourning for a form of Zionism whose time had long since passed:

Everything that is here is all temporary and they are only pretending to be farmers, only temporary vineyards and temporary orange groves, it’s only temporarily that they sink in the yielding red sand or speed over the hard bare clay, they all exist but not in the blood, not firmly grounded, nothing is solid here, the vineyard has no solid basis and the late-ripening grapes for the festivals have no solid basis nor does the farmer and it is not clear if his sons will, and all the solidity of whatever seems solid here is just the ethereal solidity of existence here, and the who knows, maybe yes and maybe no.

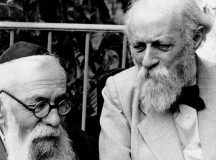

Amos Oz

After the Six Day War, Yizhar left ‘the arena of Israeli prose fiction to much younger writers,’ Miron observes, among them Amos Oz, who would take up the story of the Mandate in the three short stories that make up The Hill of Evil Counsel (1976) and the novellas Soumchi (1978) and Panther in the Basement (1995). Born in Jerusalem in 1939 into a Revisionist Zionist milieu, great-nephew of the religious scholar and one-time presidential candidate Joseph Klausner, Oz’s contributions reflect the Jerusalem of his childhood during the twilight hours of the Mandate.

His Jerusalem is provincial—’not so much a city as isolated neighbourhoods separated by fields of thistles and rocks.’ Indeed, seen through the eyes of a child, it feels like the end of the world. In The Hill of Evil Counsel’s title story, Hillel and his parents live in Tel Arza, today a Haredi neighbourhood in north Jerusalem, back then a speck on the map—a young, dusty outpost of Jewish Jerusalem established in 1931, planted with young saplings and linked to the centre by a dirt road. The Hill of Evil Counsel’s ‘Mr. Levi,’ Soumchi, and Panther in the Basement, meanwhile, roam the streets of Kerem Avraham, where Oz himself grew up. At sunset, he recalls in Soumchi, Jerusalem would smell of sauerkraut, tar and cooking oil, souring rubbish bins, and warm, wet washing hanging out to dry.

Kerem Avraham was also where the Schneller Barracks and the Russian Compound were located. Simultaneously, Jerusalem was also the centre of power and intrigue in a rapidly collapsing corner of the British Empire:

Through the window I could see the parade ground inside the Schneller Barracks. Antlike soldiers were sweeping the parade ground, whitewashing the trunks of the pines and eucalyptus trees, marking off areas with rope, piling up roof tiles. In the evening light they seemed pitifully tiny and lost, these soldiers needlessly risking their lives. …The British were finding Palestine about as comfortable as a bed of nails, as the saying went. Almost every night our windows rattled and tall flames could be seen in the strongholds of the British administration. They were getting to be like a cat on hot bricks, the saying went.

Jerusalem was on fire throughout 1946 and 1947. The Jewish community was frequently placed under stringent curfew. British police and soldiers conducted house-to-house raids in search of contraband and underground activities. All the while, up at Government House, the High Commissioner would host resplendent cocktail parties and, as Oz describes in the opening pages of The Hill of Evil Counsel, celebrations marking the Allied victory in the Second World War. ‘Vases of gladioli stood on the front of the stage. And a banner carried a quotation from the Bible: PEACE BE WITHIN THY WALLS AND PROSPERITY WITHIN THY PALACES.’

As seen through the impressionable eyes of a child, susceptible to exaggeration, prone to flights of fancy, the atmosphere among the Jews of Jerusalem was at fever pitch. The city was a crucible that forged oddballs and eccentrics, mystics and prophets, fired up by politics and haunted by the traumas of Europe. These figures populate the pages of Oz’s stories, turning up in order to make fiery, doom-laden speeches that blend political and religious messianism. At night, the lonely city echoes with ominous, foreboding noises, the wail of a distant muezzins and hungry jackals crying in the woods. Like the kibbutz in novels like Where the Jackals Howl and Elsewhere, Perhaps Oz’s Jerusalem is never at rest and disruption just around the corner.

The child’s circumscribed view means that, if Yizhar’s Preliminaries is an inward-looking novel defined by a struggle for the Jewish soul, then in Oz’s stories the fight against the external enemy, the British, is the entire world. The everyday is entirely shaped and defined by the political situation:

At dawn the boys would go round sticking posts from the Underground on walls and lampposts. On Saturday afternoons, in our backyard, there were arguments with guests and a procession of glasses of scalding tea, and biscuits that my mother made. In the course of these arguments, both the guests and my parents would use words like persecution, extermination, salvation… Occasionally one of the guests would get carried away, …and then he would hurriedly add, as though in an attempt to correct the bad impression, ‘But we must on no account allow ourselves to be split, heaven forbid, we’re all in the same boat.’

Oz’s young protagonists have a very clear and simplistic sense of what is right and what is wrong. There is nothing but the struggle for self-determination, the battle to drive the British out. Be it Proffy in Panther in the Basement or Hillel in The Hill of Evil Counsel’s title story, the resistance becomes their childhood game. Soumchi plans to run off to London, turn double agent, and kidnap the King of England, holding him ransom in return for the Land of Israel. Proffy stands on the roof of his building, squinting at the British army encampment, ‘spying on their evening roll call, noting down particulars in a notebook.’ He composes slogans that his comrades paint in black on the walls around their neighbourhood: WITH BLOOD FIRE AND SWEAT OUR FREEDOM WE’LL GET. He lays out maps upon the carpet and sketches out battle plans ‘for the lightning raid by the Underground on the key government points in Jerusalem.’ Proffy narrates, ‘Even in my dreams I defeated enemies.’

The United Nations passed its partition plan for Palestine in November 1947, and by May 1948, the British were out. ‘I only hope we don’t regret it, regret it bitterly, when we’re left here without them,’ Proffy’s babysitter, Yardena, warns. But on the night that the nations of the world divided Palestine in two, in an incident lifted more-or-less from the pages of Oz’s own life—one he would go on to describe in A Tale of Love and Darkness (2002)—Proffy’s father comes home at one o’clock in the morning, lays beside Proffy in bed, strokes his face, ‘and all of a sudden he started to talk about things that had never been mentioned in our home before, because it was forbidden, things that I had always known one mustn’t ask about and that was that’:

In a voice of darkness he told me about how it was when he and Mother lived next door to each other as children in a small town in Poland. How the ruffians who lived in the same block abused them, and beat them savagely because the Jews were all right, idle, and crafty. And how once they stripped him naked in class, at the Gymnasium, by force, in front of the girls, in front of Mother, to make fun of his circumcision. And his own father, Grandpa that is, one of the grandparents that Hitler later murdered, came in a suit and silk tie to complain to the headmaster but as he was leaving the hoodlums grabbed him and forcibly undressed him, too, in the classroom, in front of the girls. And still in a voice of darkness Father said this to me:

‘But from now on there will be a Hebrew State.’

‘Jerusalem is full of Jews used by history,’ the poet Yehuda Amichai once wrote. It is a city in which hope, like a faithful dog, runs ahead of its people to check the future, to sniff it out. At the end of Panther in the Basement, there is none of the disenchantment that characterises Preliminaries. If Yizhar was looking back, Oz in these stories was looking forward. The struggle against the British was over. A new war was about to begin.

S. Yizhar ignored the fact that Jabotinsky wrote about the Arabs in Palestine – and said that all the citizens of the future Jewish state will have equal rights, regardless of their religion, gender or ethnic origin.

He also wrote in one of his poems: “There (in the future state) there will e prosperity and happiness for the son of the Arab, the so of the Christian and for my son.”