All his life Trotsky was a consistent fighter against antisemitism. – Joseph Nedava, Trotsky and the Jews, 1971.

Of course we can close our eyes to the facts and limit ourselves to vague generalities about the equality and brotherhood of all races. But an ostrich policy will not advance us a single step … All serious and honest observers bear witness to the existence of antisemitism, not only of the old and hereditary, but also of the new ‘Soviet’ variety. – Leon Trotsky, Thermidor and Antisemitism, 1937.

The rise of Nazism in Germany led the Russian revolutionary to a global revision of his approach to the Jewish question. – Enzo Traverso, Marxists and the Jewish Question: The History of a Debate 1843-1943, 1994.

The dispersed Jews who would want to be reassembled in the same community will find a sufficiently extensive and rich spot under the sun. The same possibility will be opened for the Arabs, as for all other scattered nations. – Leon Trotsky, ‘Interview with Jewish correspondents in Mexico’, 1937.

The writings of Trotsky are a blast of clean air through the swamps of hysteria, ultra-left fantasy, vicarious Arab chauvinism, and – I think – elements of age-old antisemitism recycled as ‘anti-Zionism’ into which much of post-Trotsky Trotskyism has disintegrated on this question. – Sean Matgamna, 2001.[1]

Introduction

The classical Marxist tradition of the late 19th and early 20th centuries believed that Jewish peoplehood, along with antisemitism, would inevitably dissolve in the solvent of the coming progressive universalism.[2] Specifically, it looked to the inevitable victory of an international proletarian revolution, and the advanced stage of human civilisation it would usher in, to solve what was called ‘the Jewish Question’ once and for all.[3]

But world history went another way and Jewish history went with it: a terrifying wave of anti-Jewish pogroms in Europe and the resulting rise of the Zionist movement, the defeat of the European socialist revolution, the degeneration of the Russian Revolution into Stalinism (and antisemitism), the rise of Fascism and Nazism, the closure of the world’s borders to the Jews, and the unprecedented radicalisation of antisemitism, culminating in the Shoah, an industrial-scale genocide in the very heart of European modernity. In place of history-as-progress, then, the Jews were faced with what the cultural critic Walter Benjamin – before he committed suicide himself, trapped at the French-Spanish border as he tried to outrun the advancing Nazis – called history-as-train-wreck.[4] As a result, many Jews turned to the Zionist movement to fashion their own escape from the wreckage: mass emigration and the eventual creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine in 1948.

More than any other Marxist, it was the Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky who, in the years before his murder in 1940, broke from the unscrupulous optimism of Marxist orthodoxy on the Jewish question. This essay is about how and why he did so, the alternative approach he began to put in its place, and the relevance of that alternative for the Left today.

Isaac Deutscher, author of the classic three-volume biography, tells us that Trotsky ‘re-formulated his views on the Jewish problem’ before his death, while the scholar of antisemitism, Robert Wistrich, has praised Trotsky’s ‘important theoretical shift’.[5] For Werner Cohn, by the late 1930s Trotsky ‘saw how wrong he had been’ about the nature of antisemitism, and about the best way to tackle it.[6] The Italian Marxist Enzo Traverso has claimed that Trotsky’s late writings are ‘the most profound analysis of antisemitism that Marxist thought produced in the interwar period’ and that, despite their fragmentary character, what he calls Trotsky’s ‘global revision of his approach to the Jewish question’ amounted to nothing less than a ‘rich … but embryonic’ renewal of Marxism per se on antisemitism and the Jews.[7] Ernest Mandel, a Jew who survived the concentration camp in Dora in Germany to lead the mainstream of the Trotskyist movement for the next half century, argued that the Left had not taken the measure of the ‘new approach to the Jewish question … less simplistic and less mechanical’ that Trotsky developed in response to the rise of the Nazis. Mandel believed that ‘[His] analysis of contemporary antisemitism and his recognition of the right of self-contained Jewish populations to a territorially and politically secure national existence constitute a coherent unity and a decisive step forwards in the Marxist attitude to the Jewish question’.[8] Robert Service (in a unrelentingly hostile biography of Trotsky), insists that ‘on a single big topic he shifted his position … a homeland for Jews in the Middle East’.[9]

In the first part of the essay I explore what it was in orthodox Marxism’s approach to the Jewish Question that Trotsky revised, why he did so, and what his alternative was. I agree with Enzo Traverso about the limits of Trotsky’s late writings; they are indeed only ‘the outline of an alternative,’ best read as ‘a series of intuitions rather than a coherent and systematised conception’. It’s certainly up to us to do the work today. Still, as the Left is not exactly overrun with serious attempts to fathom antisemitism outside of ‘economistic limitations,’ it is surely wise to attend carefully to those it does have.[10]

In part two I suggest a couple of reasons why Trotsky was able to change his mind on the Jewish question. First, the course of his life, punctuated as it was by fierce battles against antisemitism of several different kinds. Second, the cast of his Marxism, sceptical as it was of those economistic simplicities, alert to national specificities, and unusually sensitive to the looming danger of barbarism. What Traverso has called Trotsky’s ‘practical … nonsystematised’ Marxism, at odds with ‘any form of evolutionist and positivist Marxism’ surely helped make possible his global revision on the Jewish question.[11] In part three, I ask if Trotsky ended his life as a Zionist. I answer ‘no, but…’ and I claim that Isaac Deutscher developed Trotsky’s approach for the era of the Jewish state in ways still relevant to today’s Left. I conclude with a suggestion: knowing about Trotsky’s war against the antisemitisms of his day can help the Left understand and confront those it faces today, including the one within its ranks.

Part 1: Trotsky ‘Global Revision’ of Marxism on ‘the Jewish Question’

Orthodox Marxism and the ‘Jewish question’

Enzo Traverso has identified six components of the dominant Marxist approach to the Jewish Question in the late 19th century. Each blocked a proper understanding of antisemitism and made an effective political response to it impossible.

First, Marxism reduced the Jewish people to an historic economic function, a commercial caste of hated usurers. Incapable of seeing the significance of culture, identity and religion, Marxism struggled to ‘understand in any depth the origins and depths of antisemitism’ or to credit either the fact or the value of Jewish peoplehood, says Traverso.[12]

Second, Marxists reduced antisemitism to either an epiphenomenon of social and economic backwardness, or a ruling class plot to divide the workers. The French Marxists were neutral during the antisemitic Dreyfus affair, dismissive of a mere spat between two wings of the bourgeoisie. The press of the Austrian social democracy, noted Mandel, contained ‘antisemitic overtones’.[13]

Third, in their proposals to combat antisemitism, Marxists managed to combine crude determinism and panglossian optimism. Antisemitism was to wither away in a quasi-automatic fashion when the material base for it – the performance of the commercial economic function by the Jews as a ‘people-class’ in feudal society – withered away, as capitalism advanced. Frederick Engels, to take just one Marxist, wrote in 1890 that economic development was rendering antisemitism laughable and anachronistic.

Fourth, Marxism was militantly assimilationist, viewing the continuation of Jewishness – Jewish religion, culture, and peoplehood – as historically reactionary, particularist, and communalist. In short, Jewishness was viewed as an embarrassing obscurantist diversion from the class struggle. This failure of vision was part of orthodox Marxism’s wider failure to adequately grasp any oppression that was not directly reducible to class. Despite Marx’s own 1864 Critique of the Gotha Programme being not just open to, but positively celebratory of, sensuous particularity and difference, most post-Marx Marxists failed to see that the concept of equality should include the equal right to be different.[14]

Fifth, Marxists failed to appreciate the Jewish question in its dimension as a national question. They struggled to adequately theorise the nation per se, elaborating lists of objective criteria while neglecting ‘the subjective processes of forming a community of culture, united by a collective destiny’. The ‘Pope’ of Marxism, Karl Kautsky, had issued his edict: the Jews were not a nation. The assimilation of the Jews was, anyway, assumed to be inevitable and progressive, so the question irrelevant. In consequence, Traverso argues, the Marxist understanding of the Jewish question in Eastern Europe was ‘deprived … of its national character,’ mis-reading antisemitism as a purely ‘economic and political problem (the role of Jewish commerce, the consequences of the antisemitic legislation, and so on)’.[15]

Sixth, Marxists rejected Zionism – the movement of Jews to establish a Jewish national home in part of Palestine – absolutely, as a reactionary nationalist response to antisemitism and a diversion from the class struggle.[16] In this vein, a youthful Trotsky had attacked Theodor Herzl as a ‘shameless adventurer’.[17]

Trotsky’s Revisionism

Trotsky’s revisionism of the 1930s amounted to three new understandings: of the nature of antisemitism, the viability of the political programme of assimilation, and the collective rights of the Jews as a people to a Jewish national home. In short, he came to think antisemitism was not going away, assimilation was a dead-end, and in a darkening world, the Jews needed a state.

Trotsky as Revisionist (1) Rethinking Antisemitism

Like other Marxists, Trotsky had long conceptualised antisemitism as an essentially pre-modern phenomenon; a hangover from feudalism which would disappear as capitalism advanced. However, in 1937 Trotsky acknowledged that capitalism was having no such effect. In truth, he wrote, ‘decaying capitalism has everywhere swung over to an intensified nationalism, one aspect of which is antisemitism’.[18] He noted that antisemitism was at its worst in the most highly developed capitalist country of Europe, Germany.

Antisemitism appears in Trotsky’s late writings as a more complex phenomenon, and this is because of what Mandel calls Trotsky’s insight into the ‘nonsynchronism of socio-economic and ideological forms’ and therefore his grasp that the transhistorical, the modern, the pre-capitalist and the capitalist sources of antisemitism were now combining in unexpected ways in particular societies.[19]

Moreover, and refining the approach further, Trotsky also understood how political entrepreneurs – i.e. political leaders and activists, whether they were Tsarist autocrats, counter-revolutionary Whites or ostensibly ‘left-wing’ and ‘anti-Zionist’ Stalinists – were manipulating antisemitism to mobilise effective political movements. For example, he warned in 1937 that ‘the [Stalinist] leaders manipulate it with a cunning skill’. He watched Stalin reach down into the Russian depths, pick up the ancient antisemitism of the peasants and the Tsars, give it a new ‘communist’ veneer by muttering about ‘Zionists’ and ‘cosmopolitans,’ and use it to delegitimise the opposition to his rule. Finally, Trotsky – the most prominent sympathiser of Freud among the Bolsheviks – also saw the unconscious and irrational sources of antisemitism, warning that: ‘Antisemitism consists not only in hatred of Jews, but also in a fear of Jews. This fear enlarges ones eyes to see non-existent things.’[20]

Trotsky as Revisionist (2): Rethinking the political programme of assimilationism

Once embraced as the only acceptable solution to antisemitism, Trotsky came late in his life to reject assimilation as a programme for the Jews as a people. (Of course, he continued to support assimilation as an option for an individual, to be pursued or not according to their own lights.) ‘During my youth,’ he wrote in 1937, ‘I rather leaned toward the prognosis that the Jews of different countries would be assimilated and that the Jewish question would thus disappear, as it were, automatically. The historical development of the last quarter of a century has not confirmed this view’.[21] Chastened, Trotsky declared that not even ‘a socialist democracy’ would ‘resort to compulsory assimilation’.[22]

In this, history had been Trotsky’s teacher. ‘He admitted that recent experience with antisemitism in the Third Reich and even in the USSR had caused him to give up his old hope for the “assimilation” of the Jews with the nations among whom they lived’, recalled Deutscher.[23] Traverso concurs: Trotsky became ‘convinced of the necessity of a national solution to the Jewish problem’ because he became ‘conscious of the impasse into which assimilation had entered’.[24]

Breaking with the assimilationist dogma allowed Trotsky to break also from the limits of that inherited Enlightenment culture from which the dogma had been derived, and which was unable to achieve ‘a synthesis between a universal conception of humanity and a recognition of human diversity’.[25] One consequence of that imaginative failure for Marxism had been its tendency to demand that the Jews (a) be satisfied with civic rights as individuals only and so (b) stop seeking collective or national rights as a Jewish people.

Norman Geras pointed out that orthodox Marxism offered the Jews only a ‘spurious universalism’ as only the Jews were being told to ‘settle for forms of political freedom in which their identity may not be asserted collectively’.[26] Joel Carmichael, author of a study of Trotsky, put it particularly bluntly: ‘ … all classical Marxism had to tell us was that the Jews, having survived for discreditable reasons, should finally toss in the sponge and vanish.’[27] Traverso says the gravitational pull of Enlightenment culture on Marxism meant that Marxists wanted to emancipate the Jews ‘without recognising them’.[28] The assimilationist dogma, he argued, was one cause of the ‘constant attempt to suppress the Jewish problem’ within the Marxist movement.[29] Rosa Luxemburg, for example, argued that ‘[f]or the disciples of Marx and for the working class the Jewish question as such does not exist’. Traverso warned that ‘this repression has continued until today’.[30]

Trotsky as Revisionist (3) Rethinking the rights of the Jews: from cultural autonomy to a territorial solution

‘Trotsky’s thinking on the Jewish question’ argues Traverso, ‘would experience a remarkable evolution: during the 1930s: he admitted the existence of a Jewish nation, culturally living and modern, that had to be defended against the Nazi menace’.[31] In addition to his long standing commitment to civic rights for Jews as individuals and the right of Jews as a collective to cultural autonomy, Trotsky now also embraced the rights of a ‘Jewish nation’ which he believed would ‘maintain itself for an entire epoch to come’.[32] Trotsky came to believe the Jews had a democratic right to a Jewish national home, but he thought only socialist revolution could achieve it. ‘If the Jewish workers and peasants asked for an independent state, good – but they didn’t get it under Great Britain. But if they want it, the proletariat will give it. We are not in favour, but only the victorious working class can give it to them.’[33] He now spoke of the ‘territorial base’ for the Jews as a ‘compact mass,’ ‘in Palestine or any other country,’ after ‘great migrations’.[34] Deutscher had no doubt that in these years Trotsky ‘arrived at the view that even under socialism, the Jewish question would require a “territorial solution” i.e. that Jews would need to be settled in their own homeland’.[35] ‘A workers government’ wrote Trotsky, ‘is duty-bound to create for the Jews, as for any nation, the best circumstances for cultural development (emphasis added)’. This may entail, he wrote, ‘a separate territory for self-administration and development’.[36] He dismissed the territory set aside for the Jews in Russia, Biro-bidjan, as ‘a bureaucratic farce’.[37]

By 1937, aware of the Zionist movement, Trotsky argued that ‘the very same methods of solving the Jewish question which under decaying capitalism have a reactionary and utopian character (Zionism) will, under the regime of a socialist federation, take on a real and salutary meaning,’ asking ‘how could any Marxist or even any consistent democrat object to this’?[38] So, even though he thought only a socialist revolution was capable of enabling a ‘great migration’ of the Jews, Trotsky plainly thought desirable something akin to what we would today call ‘the two states for two peoples’ solution. How else are we to interpret this statement: ‘The dispersed Jews who would want to be reassembled in the same community will find a sufficiently extensive and rich spot under the sun. The same possibility will be opened for the Arabs, as for all other scattered nations.’[39] Why mention ‘the Arabs’ if the spot he had in mind was not Palestine, but in Eastern Europe?

One can detect absolutely nothing in Trotsky of the contemporary Left’s tendency to treat the Jews as some kind of a ‘bad people’ undeserving of the collective rights of other peoples. For example, when invited in 1934 to define the clashes in Palestine between Jews and Arabs as what would today be called ‘progressive’ or ‘anti-imperialist resistance to Zionism,’ Trotsky refused. Making a distinction which would see him drummed out of most Trotskyist gatherings today, he said he would need more information to gauge the relative significance of ‘national liberationist’ elements as opposed to ‘reactionary Mohammedans and antisemitic pogromists’.[40]

Trotsky revised his thought about the character of antisemitism, the political programme of assimilation, and the necessity of, and the Jews right to establish, a Jewish homeland. But in what ways did the course of his life and the cast of his Marxism equip Trotsky to make that ‘global revision’? To that question I now turn.

Part 2: His Life – Trotsky Against Antisemitism

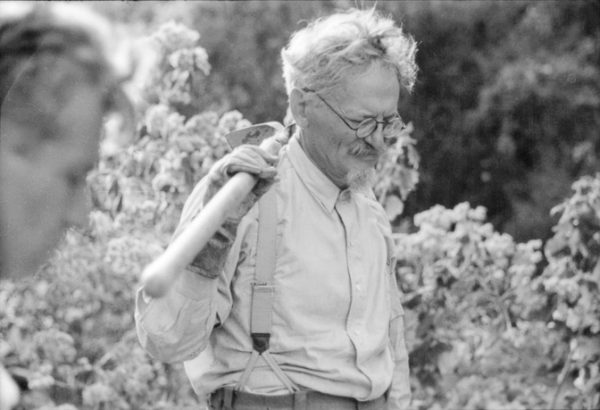

Trotsky’s had never been a culturally or religiously ‘Jewish’ life. As a universalist and an atheist he ‘hated it when people emphasised his Jewish background’.[41] The American socialist Max Eastman believed ‘Trotsky was as little bothered about, or influenced by, his being a Jew as any Jewish person I ever knew’.[42] Of himself, Trotsky said: ‘I have lived my whole life outside of Jewish circles. I have always worked in the Russian workers movement. My native tongue is Russian. Unfortunately I have never even learned to read Jewish. The Jewish question has, therefore, never occupied the centre of my attention.’

But Trotsky immediately added, ‘This does not mean that I have the right to be blind to the Jewish problem which exists and which demands a solution.’ [43] It is not only that ‘Trotsky neither uttered nor ever wrote anything against his people which might be indirectly taken as casting aspersions on his ancestry’.[44] It is that Trotsky had ‘a much greater feeling of solidarity with the victims of antisemitism than was the case with Kautsky, Viktor Adler, Otto Bauer or even Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg’.[45] He may have wanted to be what Isaac Deutscher once called a ‘non-Jewish Jew’ – i.e. one of those Jewish-born internationalist-universalist men and women of world culture such as Spinoza, Marx, Luxemburg, and Freud – but the world would not let him be only that. Instead, his life was punctuated by episodes of passionate opposition to the antisemitism of Left and Right, practical solidarity with its Jewish victims, and intellectual reflection on the origins, psychologies and political uses of antisemitism.

Nedava points out that ‘even quantitatively speaking, he dealt with Jewish topics perhaps more than any other Jewish or non-Jewish Bolshevik,’ and that ‘no other Jewish (or for that matter non-Jewish) Bolshevik leader – including Lenin – dealt with the Jewish problem as extensively, albeit unsystematically and fragmentarily, as Trotsky’. [46] While Trotsky tended to down play this record for obvious Russian reasons, Joshua Rubinstein’s judgement is fair: ‘When Jews are oppressed, Jews are threatened, Jews are physically attacked, [Trotsky] responds in very vehement, and sometimes courageous ways.’[47] A review of some of those battles can reveal how they may have shaped his later rethink of the Jewish question.

1899 and 1903: Antisemitic Pogroms

Trotsky learned early that antisemitism could be irrational, murderous, and popular. The antisemitic pogroms of 1899 had been ‘a deeply traumatic experience for Trotsky as a child’ claims Nedava, and this ‘accounts for the matter always being on his mind … a recurring theme’ in his writing.[48] When 24 years old, Trotsky reacted with fury to the antisemitic Kishinev pogrom of 1903. Although he was already a Russified atheist revolutionary, the pogrom ‘affected him deeply,’ and we can find thereafter ‘many references [to it] in his writings and speeches’.[49]

1905: Antisemitism and the Russian Revolution

In the 1905 revolution Trotsky was confronted by the political utility of antisemitic pogroms to the Tsar, the autocracy and the Church, and by the undeniable emotional and psychological satisfactions that antisemitism provided to the pogromists.[50] Rubinstein notes it was because it was led by Trotsky that the 1905 revolutionary Soviet (or Council) ‘recognised the need to defend the Jews from pogroms’. Throughout the revolution, Trotsky ‘never abided physical attacks on Jews and often intervened to denounce such violence and organise a defense’, creating armed units in St Petersburg, some ‘twelve thousand men, armed with revolvers, or with wooden or metal clubs’, who ‘effectively forestalled the regime’s [antisemitic] attacks’. [51]

When a Jewish student from Nikolayev asked to meet Trotsky to discuss self-defence he was told by Trotsky, ‘You should know that we have entered into an agreement with the heads of the local Zionists with the object of establishing a common self-defence organisation. This will consist of your Zionist friends and members of the Russian Social-Democratic Party.’ Later, Trotsky advised the student to link up with Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s armed Zionist self-defence group in Odessa.[52]

Norman Geras, in a brilliant essay making the case that many of Trotsky’s writings are a literature of revolution, argues that Trotsky learned in the 1905 revolution of the ‘inexhaustible reserves … of darkness, ignorance and savagery’ which lie in ‘the depths of society’. Picking out Trotsky’s description of a pogrom, Geras discerns in its acute insight and deep empathy the twin sources of the foresight that allowed Trotsky, perhaps alone, to predict the Holocaust in 1938. Here is the passage Geras cites, from Trotsky’s book 1905:

The gang rushes through the town, drunk on vodka and the smell of blood. The doss house trap is king. A trembling slave an hour ago, hounded by police and starvation, he now feels himself an unlimited despot. Everything is allowed to him, he is capable of anything, he is the master of property and honour, of life and death. If he wants to, he can throw an old woman out of a third-floor window together with a grand piano, he can smash a chair against a baby’s head, rape a little girl while the entire crowd looks on, hammer a nail into a living human body … he exterminates whole families, he pours petrol over a house, transforms it into a mass of flames, and if anyone attempts to escape, he finishes him off with a cudgel. A savage horde comes tearing into an Armenian almshouse, knifing old people, sick people, women, children … there exist no tortures, figments of a feverish brain maddened by alcohol and fury, at which he need ever stop. He is capable of anything, he dares everything.[53]

As Geras comments, being drunk on blood is hardly an orthodox Marxist category, yet it was one Trotsky was willing to turn to in order to explain antisemitic savagery.

1912-1913: The persecution of the Romanian Jews

Trotsky came to understand more about the national specificities of antisemitism when covering the First and Second Balkan wars as a journalist in 1912-1913. The experience produced ‘his most extensive writing about the fate of his co-religionists’ as he turned his attention to the terrible persecution of the Romanian Jews.[54] While Trotsky admitted he could not personally respond to their ‘religious melodies and national superstitions,’ he did rail against their ill-treatment: the absence of civic rights, the forced military service, the abuse and the violence. More: Trotsky registered his ‘profound disgust’ at the sordid financial and diplomatic deals that kept things that way. Again, moral outrage and social analysis were combined. The Jew, he wrote, was the ‘lightening rod for the indignation of the exploited,’ while up above there was the King’s ‘mystic fear’ of Jewish financial power. For Romania as a whole, antisemitism had become ‘a state religion – the last cementing factor of a feudal society rotten through and through’.[55]

1913: The Beilis Blood-Libel Trial

Trotsky’s intellectual understanding of antisemitism was inseperable from his personal empathy with the persecuted Jew. As a journalist, Trotsky reported on a blood libel trial in Kiev in 1913. After a 12-year old gentile boy was murdered and his body thrown into the Dnieper River, a Jewish brick factory worker called Beilis was framed for the crime. Beilis was accused of using the boy’s blood to prepare Matzos for the Jewish Passover holiday – a Medieval antisemitic lie still doing service to Jew-haters in the 20th century (and to antisemitic Islamists like Raed Saleh in the 21st century).[56] Trotsky developed an ‘ardent interest’ in the case and a mastery of its details.[57] His reporting exhibited not only a profound identification with the accused Jew, but some analytical brilliance about the complex reasons for his persecution. He showed how the following co-mingled: popular ignorance and the satisfaction of deep emotional needs of the poor; elite manipulation and political calculation; and even international diplomacy and financial intrigue.

The trial transcript produced ‘first and foremost … a feeling of physical nausea’ in Trotsky, such that he ‘could not restrain his anger [and] sarcastic fury’ at this grotesque miscarriage of justice.[58] This fury was reflected in his writing:

When an ordinary Jewish worker … is suddenly torn away from his wife and children, and is told that he has drained out the blood of a living child, with a view to consuming it, in one form of another to the joy of his Jehovah, then one need only visualise for a moment the state of this wretch during twenty-six months of isolated imprisonment to cause one’s hair to stand on end. Every effort was done to instil hatred towards Beilis as a Jew in the … jury.[59]

It may be said that the willingness of Trotsky to ‘visualise’ i.e. to empathise deeply with the persecuted Jew, is no great achievement. But it was not an achievement of every Marxist, to say the least. Again, we may offer the example of Rosa Luxemburg, who wrote angrily to a friend from her prison cell, ‘What do you want with this theme of the “special suffering of the Jews”? … [there are] so many cries of anguish [that] have faded away unheard, they resound within me so strongly that I have no special place in my heart for the ghetto.’ Well, Trotsky did. And as Ronald Segal has argued, that Trotsky ‘saw the plight [of the Jews] for the special one that it was can scarcely be dismissed as unimportant, when so many of his revolutionary colleagues with Jewish origins chose rather to avoid or deny it’.[60] A quarter century later, with Europe on the edge of catastrophe, Trotsky was still invoking ‘the image of a poor, lonely Jew falsely accused of killing a Christian child’.[61]

January 1917: The ‘Trotsky-Conspiracy’ in New York City

Trotsky gained first hand experience of the conspiracism that lies at the heart of all antisemitism when he arrived in New York City via Barcelona in January 1917 and lived there for ten weeks en route to revolutionary Russia. He threw himself into agitation against a war that the US would enter three months later, publishing articles in the New York Yiddish press. What then broke over his head was ‘The Trotsky-Jewish conspiracy’ or ‘The Jewish Plot’. ‘The idea was spread that Jewish bankers had paid Trotsky to overthrow the government and create Bolshevism’ says Kenneth Ackerman, author of a study of this period. The conspiracy seems to have been birthed within US and British Military Intelligence. ‘Trotsky was being tracked by British intelligence at the time,’ explains Ackerman, ‘and several of the people the British had on their payroll were people from Russia with clear track records of antisemitism’ including Boris Brasol. Copies of the antisemitic fraud ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion’ were circulated to American and British Military Intelligence by Brasol, ‘making the case that Jews were running Bolshevism,’ and that the chief Jewish conspirator was Leon Trotsky.[62] As a result, Trotsky was arrested en route to Russia by police in Canada and held as a prisoner of war in Nova Scotia for a month. The conspiracy theory remained part of the antisemitic propaganda of the US Nazi movement throughout the inter-war period.[63]

1917: The Russian Revolution and Antisemitism

Whatever criticisms can be made of the Bolsheviks during the early years of the revolution, when Trotsky was influential on policy,[64] the decision to appoint a Jew, Jacob Sverdlov, as the first president of the new Soviet republic has rightly been described as ‘an act of courage whose importance should not be underestimated; it was a declaration of war against antisemitism, now identified with the counter-revolution’. And in July 1918 a decree was passed outlawing antisemitism, promising harsh measures against pogromists and declaring antisemitism ‘a mortal danger for the entire revolution’.[65] The result was that ‘the party’s leadership was widely identified as a Jewish gang’.[66]

The revolution taught Trotsky about the ubiquity of antisemitism. He saw that it was present among the revolutionary as well as the counter-revolutionary armies. Trotsky fought antisemitism in the Red Army he led as Peoples Commissar for War. In July 1920, when Trotsky heard that some Red Guards were attacking Jews in Novorossiysk, ‘his intervention brought an end to the pogrom’.[67] Traverso records that Trotsky ‘punished three regiments accused of having organised pogroms and attempted by every means to stop such events recurring’.[68] Keen for Jews to serve in the Red Army to undermine antisemitism, Trotsky tried to establish Jewish fighting units. Under his leadership, the Peoples Commissariat for War set up a section ‘dedicated to making propaganda against pogroms’.[69] During the civil war, whenever the Red Army was itself guilty of antisemitism‘ Trotsky ‘rushed to the place of their occurrence to supervise personally the punishment of the perpetrators’.[70]

The counter-revolution practiced antisemitism of entirely different scale and intensity however, and this also educated Trotsky. Symon Petlyura (a man honoured in Ukraine in 2017) led the murder of 50,000 Jews by the counter-revolution in Ukraine in 1918-1921, most of the victims being women, children and older people. It was ‘a traumatic shock to Trotsky’ and the memory of it, the knowledge of what was possible, surely informed his prediction about the Nazis in 1938 as well as his shift to explicit support for a Jewish homeland.[71]

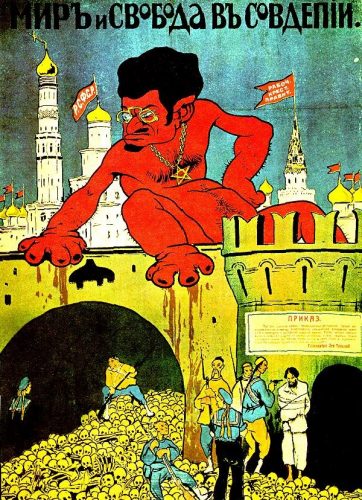

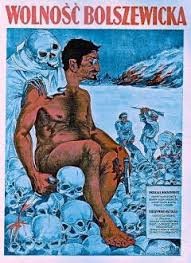

Trotsky himself soon became the target of antisemitism from the counter-revolution. Posters about him were ‘routinely Judeaophobic’. He was cast as an alien to Russia, a ‘cosmopolitan Jew’ and – years before Hitler took up this theme – a ‘Jewish Bolshevik’.[72] The leaders of the counter-revolution lied that ‘the Jew Trotsky’ was turning churches into movie theatres and forcibly circumcising peasants. Pogromists would scream, ‘Down with Trotsky!’ as they attacked Jewish villages and towns.[73] He was turned into the ‘demonic symbol of Judeo-Communism for antisemitic gentiles’ and the personification of ‘the evil influence of the Jews’.[74] He was depicted (see below) as the gross, naked ogre of the Kremlin, a powerful giant, but one shaped according to antisemitic tropes: the Jew bespectacled and intellectual, hooked-nose, wearing a Star-of-David, wading in the blood of the Gentiles or imperious on top of a mountain of Gentile skulls. No wonder he understood that antisemitism was about an irrational fear of Jewish power.

The 1920s and 1930s: Stalin and Left Antisemitism

Trotsky came to know a lot about Left antisemitism. During the inner-party struggle of the 1920s Stalin repeatedly used Trotsky’s Jewishness against him. By 1926, the dictator was openly using the fact that the three leaders of the United Opposition – Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev – were Jews, to defeat them, and later made sure their original Jewish names were used in Soviet press reports of their show trials and executions.

When the persecution of Trotsky’s son Sergei was approaching its deadly end, the Russian press routinely used the Jewish sounding ‘Bronstein’ as Sergei’s family name – not ‘Sedov’ or ‘Sedova’, his legal name after his mother Natalia, and not ‘Trotsky,’ his father’s name since his pre-revolutionary Siberian exile. Stalin also spread the lie that Sergei was guilty of preparing a mass poisoning of workers. Trotsky immediately saw this not just as a lie but an antisemitic one: ‘My son is accused,’ he wrote, ‘not more nor less, of an attempt to exterminate workers. Is this really so far from the accusation against the Jews of using Christian blood?’[75] In 1937, in the essay Thermidor and Antisemitism, Trotsky drew a balance sheet. ‘History’ he concluded, ‘has never yet seen an example when the reaction following the revolutionary upsurge was not accompanied by the most unbridled chauvinistic passions, antisemitism among them’. He felt the Stalinist counter-revolution in Russia was no exception. ‘To reinforce its domination the bureaucracy does not even hesitate to resort … to chauvinistic tendencies, above all, to antisemitic ones.’

The Moscow Trials may be a byword for Soviet injustice and Western leftist intellectual gullability and apologia, but Trotsky pointed out what few have: they were also antisemitic events. ‘In all such trials the Jews inevitably comprise a significant percentage, in part … the leading cadre of the bureaucracy at the centre and in the provinces strives to divert the indignation of the working masses from itself to the Jews. This fact was known to every critical observer in the USSR as far back as ten years ago…’[76] In 1937 when he arrived in Mexico he told local journalists that: ‘The latest Moscow trial, for example, was staged with the hardly concealed design of presenting internationalists as faithless and lawless Jews who are capable of selling themselves to the German Gestapo. Since 1925 and above all since 1926, anti-semitic demagogy, well camouflaged, unattackable, goes hand in hand with symbolic trials against avowed pogromists.’[77]

Trotsky’s pain and shock as this antisemitic campaign unfolded inside the Communist party was expressed in a letter to Nikolai Bukharin: ‘Is it true, is it possible, that in our Party, in Moscow, in WORKERS’ CELLS, anti-Semitic agitation should be carried on with impunity?!’[78] When Trotsky raised the matter at the Politburo he was met with ‘denials or a silent embarrassment’.[79] However, in a development common to all episodes of Left antisemitism, there were plenty of left-wing pro-Stalin Jews in Russia and abroad who were neither silent nor embarrassed. They went on the offensive, attacking Trotsky for smearing Stalin with false charges. These ‘Jewish Voices for Stalin,’ as we might call them, were useful idiots. One, B.Z. Goldberg, writing in the New York Yiddish daily Der Tog, claimed ‘there is no antisemitism in the life of [the Soviet Union] … it is therefore unforgivable that Trotsky should raise such groundless accusations against Stalin’.[80] Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

The entire revolutionary experience had been unrelenting in driving Trotsky to revise his views on the Jewish question. Mandel suggests that soon after 1917 Trotsky ‘became increasingly aware of his own Jewish origins and of the political reaction to this in significant sections of the Russian population’.[81] In 1922, when Trotsky refused Lenin’s request to become the first deputy chairman of the Council of Peoples’ Commissars (in effect, Lenin’s No. 2) he cited his Jewish heritage as the reason. Trotsky, says Mandel, was ‘more aware than the other revolutionary leaders, including Lenin, of the potential horrors of active antisemitism’.[82] In 1930, exiled and hunted, Trotsky almost titled his autobiography ‘The Planet without a Visa’ (he used the phrase for its final chapter instead). By the later 1930s, thinks Norman Geras, Trotsky had registered that ‘his situation now resembled in certain ways the situation … of the people from whom he had come’.[83]

1933-1940: The Nazis as ‘final stimulus’

It is often said that no one predicted the Holocaust, but that is not true. In December 1938 Trotsky issued this warning. ‘The number of countries which expel the Jews grows without cease. The number of countries able to accept them decreases. It is possible to imagine without difficulty what awaits the Jews at the mere outbreak of the future world war. But even without war the net development of the world reaction signifies with certainty the physical extermination of the Jews.’

It was the rise of the Nazis that ‘provided the final stimulus for Trotsky to change his position on one decisive aspect of the Jewish question’ writes Mandel. And from 1937 ‘he recognised the right of the Jewish nationality to its own state at least in those territories in which it constituted a self-contained population with its own language’.[84] Hitler provoked Trotsky’s revisions because the Jewish question now ‘came to assume the proportions of a global emergency’.[85] Robert Service also believes that it was only after Hitler came to power in 1933 that Trotsky decided ‘a specific set of measures had to be designed to avert the extinction of world Jewry’.[86]

Today, many understandably fear that a robust anti-capitalism can become an antechamber to antisemitism. They see the return of a blatantly antisemitic discourse about ‘Rothschild-Capitalism’ and ‘Jewish Bankers’ spreading across the alt-Right and the far Left. Parts of today’s Left are making anti-capitalism frightening to Jews. It is the task of anti-capitalists to understand that, and to purge their discourse of any footholds for antisemitism. For his part, Trotsky looked at Germany in the 1920s and 1930s and was in no doubt that capitalist crisis was a major cause of the ‘monstrous intensification of chauvinism, and especially of antisemitism’ that the Nazis fed off.[87]

In the epoch of its rise, capitalism took the Jewish people out of the ghetto and utilised them as an instrument in its commercial expansion. Today decaying capitalist society is striving to squeeze the Jewish people from all its pores; seventeen million individuals out of the two billion populating the globe, that is, less than one per cent, can no longer find a place on our planet! Amid the vast expanses of land and the marvels of technology, which has also conquered the skies for man as well as the earth, the bourgeoisie has managed to convert our planet into a foul prison.[88]

Trotsky’s came to see that, in his arresting phrase, a crisis-ridden capitalism can cause society’s old and ‘undigested barbarism’ to be vomited up. ‘The content of the category of barbarism’, explains Geras, is ‘essentially anthropological’ referring to ‘obsessive unreasoning hatreds, extreme and endemic violence, the enjoyment of cruelty, indifference to great suffering and so forth’.[89] Trotsky, Geras insisted, grasped that a distinguishing feature of contemporary antisemitism was this ‘combination … of old and new ideological forms’.[90]

To sum up: the first broad reason Trotsky was able to carry out his global revision on the Jewish question was that his life had been spent in practical resistance to antisemitism and deep reflection on that experience. I believe the second broad reason was the cast of his Marxism.

Part 3: His Thought – Trotsky’s Critical Marxism

Robert Wistrich’s study of the attitude of the far left towards the Jews – which he characterises as a journey from ambivalence to betrayal – claimed that it was Marxism’s ‘economistic superficiality’ that was the major cause of its failure to see plain the ‘fundamentally demonic view of the world’ of the antisemite, or to grasp the ‘mythical power of antisemitic stereotypes of the Jew’.[91] In similar vein, Traverso has argued that it was orthodox Marxism’s ‘reduction of Jewish otherness to commerce, a socioeconomic function that the Jews had fulfilled over several centuries’ that ensured ‘the entire Marxist debate’ was reduced to ‘one problem: assimilation’. The result was that Marxism as a whole ‘remained the prisoner of a single interpretation of Jewish history, inherited to a large extent from the Enlightenment, which identified emancipation with assimilation and could conceive the end of Jewish oppression only in terms of the overcoming of Jewish otherness’.[92] From Karl Marx’s ‘geldmensch’ to Karl Kautsky’s ‘caste’ and Abram Leon’s ‘people-class’ we find these same dogmatic economistic simplicities.

Beyond the Philosophy of Progress

Trotsky was different not only because he had a wide experience of fighting several different forms of antisemitism but because he then allowed his experience to shatter the simplistic framework of his thinking. I think this was possible for him because he had already taken his distance from all Marxist versions of the Enlightenment philosophy of progress.[93]

In place of Marxism’s overconfident expectation of a linear and progressive historical development, Trotsky saw plain both the non-simultaneity and non-linearity of history, and the possibility of catastrophe.[94] A year before he died, Trotsky faced up to the possibility that the proletariat could ‘prove incapable of accomplishing its mission’ and the socialist programme could ‘peter out as a utopia’. In such a situation, he thought the new task would be to ‘defend the interests’ of the exploited and oppressed come what may.[95] Something of this sensibility is surely at play in his late revisionist thinking on the Jewish question. It was a sensibility that Deutscher would render tragic and develop into a democratic Left programme for the era of the Jewish state, as I discuss in the conclusion.

An undogmatic theory of the nation

Trotsky was able to embrace the idea of the Jewish nation because, contra to the Stalinist caricature of Trotsky as a national nihilist and romantic internationalist, his thought was marked by an acute understanding of ‘national peculiarities and uniqueness’.[96] Traverso has shown that he possessed an ‘original … dialectical, open, and undogmatic theory of the nation’ based on a ‘fundamentally cultural-historical conception’ of what a nation is. He was completely understanding of the subjective or ‘invented’ character of peoplehood and national consciousness.[97] As early as 1915, he argued that ‘the nation constitutes an active and permanent factor in human culture’. Moreover, he believed ‘the nation will not only survive the current war, but also capitalism itself. And in the socialist regime, the nation, freed of the chains of economic and political dependence, will for a long time be called upon to play a fundamental role in historical development’. I believe this kind of insight, so infrequently heard today, also enabled his radical rethinking of the Jewish question in the late 1930s, in particular his understanding that ‘[t]he territory, language, culture, and history of a people … even if they did not always coexist, materialised the nation’. [98]

Part 4: ‘A rich spot under the sun’ – Did Trotsky become a Zionist?

The establishment of a territorial base for Jewry in Palestine or any other country is conceivable only with the migrations of large human masses. Only a triumphant Socialism can take upon itself such tasks. Leon Trotsky, 1934.[99]

Did Trotsky become a Zionist, then? Joseph Nedava, author of Trotsky and the Jews, claimed so in an exchange with Joel Carmichael, one of Trotsky’s biographers. In the late writings and interviews, wrote Nedava, Trotsky was ‘subscribing indirectly to the Zionist solution’ and had he lived, ‘would have sanctioned this historic fact, even if only as a “temporary” solution to the Jewish problem’.[100] Carmichael, while he accepted that given the situation in Europe Trotsky had been ‘forced to accept a territorial solution,’ insisted ‘he did not become a Zionist, even theoretically’.[101]

I think both are right.

Yes, it is possible to simply point to Trotsky’s statements decrying Zionism, and move on.[102] But things are more complicated than that. Consider: we have already seen that Trotsky believed assimilationism as a political programme for the Jews was bankrupt and that the physical destruction of the Jews was imminent. And we have seen that, as a result, he supported the idea of a ‘mass migration’ of the Jews, who had the right to live as a collective in a ‘compact mass’ in a ‘territory,’ ‘in Palestine or elsewhere’. Could those commitments not be said to amount to support for a programme akin to ‘Zionism’?

I think Sean Matgamna has put it best: what Trotsky was proposing in the late 1930s, as the skies darkened, was ‘a different, socialist version of the Zionist territorial state-creating solution’. After all, what else can be meant by his statement that ‘The very same methods of solving the Jewish question which under decaying capitalism have a reactionary and utopian character will under the regime of a socialist federation, take on a real and salutary meaning’? Why else would he then have added, as he did, that ‘the Arabs’ would of course have their own equally ‘extensive and rich’ spot under the same sun? It was because he anticipated the reaction from the Left to this early version of the two-state solution that Trotsky asked ‘how could any Marxist or even any consistent democrat object to this?’ I believe Ernest Mandel is right when he says Trotsky did not became a Zionist and when he says Trotsky ‘would not have rejected the right to a limited state-political autonomy for the Hebrew-speaking minority in Palestine’.[103]

Trotsky proposed a socialist version of the Zionist state-creating solution because he thought Zionism itself was incapable. ‘There can be no doubt’ he wrote in 1934, ‘that the material conditions for the existence of Jewry as an independent nation could be brought about only by the proletarian revolution’. In 1937, again: ‘Only a triumphant socialism can take upon itself such tasks,’ and only the ‘complete emancipation of humanity can solve the Jewish question’. In July 1940, after Britain changed policy and became hostile to the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine, Trotsky thought his position had been vindicated. But he took no joy in that. He was fearful: ‘The attempt to solve the Jewish question through the migration of Jews to Palestine can be seen for what it is, a tragic mockery of the Jewish people.’[104]

History proved Trotsky wrong of course. His state-creating solution to the Jewish question did happen in 1948, but not by his method. It was Zionism and the Haganah, not the international proletariat led by the parties of the ‘Fourth International,’ who created it. Israel was not a ‘tragic mirage,’ as Trotsky forecast, but a real-world refuge for the traumatised Jewish survivors of the Holocaust and the Farhut, the expulsion of some 700,000 Jews from the Arab lands in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Trotsky may have thought that ‘salvation [for the Jews] lies only in revolutionary struggle’ but for the Jews who made it to Palestine, salvation lay in auto-emancipation and sovereignty it created there. Post-war Marxists would respond to this new reality in radically different ways.

Conclusion: Trotsky’s ‘Rich Spot in the Sun’, Deutscher’s ‘Burning Building’, and Us

In 1954 Deutscher looked back at Trotsky’s advice to the powerless Jews of Europe about to be murdered by a bestial enemy – that they should stay and fight for world socialist revolution.

I have, of course, long since abandoned my anti-Zionism, which was based on a confidence in the European labour movement, or, more broadly, in European society and civilisation, which that society and civilisation have not justified. If, instead of arguing against Zionism in the 1920s and 1930s I had urged European Jews to go to Palestine, I might have helped to save some of the lives that were later extinguished in Hitler’s gas chambers. For the remnants of European Jewry – is it only for them? – the Jewish state has become an historic necessity. It is also a living reality.

And Deutscher knew something else. Precisely because Israel was created not by Trotsky’s benign World Socialist Federation allocating rich spots in the sun to the various stateless peoples who demanded them, but only after the Second World War, the Holocaust, and the vicious local war between Jews and the Arabs from 1947 to 1949, the new state could not be simply a refuge state for the Jews. After the fighting, for the Palestinians, it was a land lost. Deutscher captured the genuinely tragic quality of that history for both victim peoples, and its implications for them and for the Left, in his famous image of mid-century Europe as a burning building.

A man once jumped from the top floor of a burning house in which many members of his family had already perished. He managed to save his life; but as he was falling he hit a person standing down below and broke that person’s legs and arms. The jumping man had no choice; yet to the man with the broken limbs he was the cause of his misfortune.

If both behaved rationally, they would not become enemies. The man who escaped from the blazing house, having recovered, would have tried to help and console the other sufferer; and the latter might have realised that he was the victim of circumstances over which neither of them had control.

But look what happens when these people behave irrationally. The injured man blames the other for his misery and swears to make him pay for it. The other, afraid of the crippled man’s revenge, insults him, kicks him, and beats him up whenever they meet. The kicked man again swears revenge and is again punched and punished. The bitter enmity, so fortuitous at first, hardens and comes to overshadow the whole existence of both men and to poison their minds.[105]

Deutscher’s metaphor is not perfect, of course. Palestinians may point out that Zionism was more knowing and strategic than the image of a spontaneous ‘leap’ suggests (as well as asking, reasonably, ‘why us?’) The Jews may say the UN proposal to partition the land was the rational solution, that it was accepted by the Jews but, tragically, rejected by the Arabs. And many Jews will object that Deutscher rests the claim of the Jews to a national home in Palestine solely on an emergency – the rise of eliminationist antisemitism in mid-century Europe and the closing of the doors to the Jews by the states of the world – ignoring the Jews’ millennia-long relationship to the land.

And yet, even after acknowledging the force of all these objections, I confess that ever since I was introduced to Deutscher’s metaphor almost 40 years ago as a young member of a small group of left-wing socialists in the British Labour Party, Socialist Organiser, it has seemed to me to be both (a) the analytical alternative to ‘settler-colonialism’ or ‘God’s will’ as an explanation of the conflict and (b) the political alternative to those all-or-nothing maximalisms that are proposed by the extremists, whether Arab or Jewish, as a political programme to resolve the conflict.[106] For those on the Left who would continue in the spirit of the late Trotsky while recognising both the right of the Jewish state to endure and the Palestinian state to come into existence, Deutscher’s approach has much to recommend it: a tragic sensibility, a commitment to consistent democracy, and a belief in deep mutual recognition not ethnic exclusivism. For myself, that points to ‘two states for two peoples’ and, in time, who knows, to the mutual acceptance that could made possible relatively porous borders and more besides, much more than we imagine today.

Its 2019: why bother with Leon Trotsky?

Where has the [Labour antisemitism] crisis come from? From five decades of political and moral ferment on the ostensibly ‘Trotskyist’ Left in which absolute hostility to Israel, to any Israel, has slowly built up in the political atmosphere like poisonous smog. During the Blair-Brown epoch, that ‘revolutionary’ Left was excluded and self-excluded from the Labour Party. The ‘Corbyn surge’ that recreated a mass membership almost overnight pulled into the new, new Labour Party a lot of people educated on the Middle East question in the kitsch Left. With them they brought their political baggage, and a trolling and bullying culture. – Sean Matgamna. [107]

Trotsky matters because since the late 1960s, Trotskyism has been an influence on much wider circles of the Left, and has even been capable of exercising a decisive influence from time to time. Paul Le Blanc is probably right that we are entering a new ‘Trotsky moment,’ as a result of the ‘re-emergence of capitalist crisis, radical ferment and global insurgencies in our own time’.[108] Trotsky also matters because post-Trotsky Trotskyism has not followed in the tracks Trotsky laid down in his late revisionism on the Jewish question. Instead, it has gone off in a different direction altogether, being shaped decisively by (a) the ‘anti-Zionist’ campaigns of the Stalinist and Arab states, and (b) the politically crude, romantic Third Worldism of the young ‘New Left’ which transformed the wider Left from the 1960s and taught it to view the world and everything in it as composed of just two ‘camps,’ variously described as good and bad, oppressed and oppressor, the imperialised and imperialist, Empire v Resistance, and so on.

The story of the Stalinist roots of contemporary left antisemitism has not yet found its historian.[109] But in 1980 the British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm – a sharp critic of Israel – did warn about a new form of antisemitism, one ‘dressed up’ as anti-Zionism, as he put it. Across huge tracts of the world, he noted, antisemitism had never gone away. It had survived in two major regions in the post-war years – ‘under Islam and, unfortunately, in some countries committed to an ideology which rejected racism, notably the Soviet Union’. Although Hobsbawm was himself a lifelong member of the Communist Party, he pointed out that across Stalinist Eastern Europe, ‘antisemitism … was … tolerated and sometimes encouraged’ after the Holocaust, ‘albeit now dressed up as “anti-Zionism”’.[110]

It is this ‘antisemitism dressed up as anti-Zionism’ that has now plunged the British Labour Party into crisis. Sean Matgamna, one of most acute observers of the disastrous impact of Stalinism on the international Left,[111] points out that the legacy of the Stalinist campaigns are still with us: ‘[Antisemitism] spread to the Left from the USSR and the satellite countries, where, after World War 2, official government anti-Zionism provided a new flag of convenience for the Judeophobia long endemic there.’ Matgamna goes on: ‘This official Left “anti-Zionism” spread from the East throughout the labour movement. It spread to the non-Stalinist Left partly by way of Stalinist influence, partly as a by-product of the Left’s proper involvement with campaigns against colonialism and imperialism.’

The consequence has been the intellectual and moral disarmament of a part of the left in the face of fascistic antisemitic movements that are hostile to all left-wing, democratic and feminist values. At its worst, some now even offer up hymns of solidarity and praise to Hamas, Hezbollah and former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmedinijad as their ‘friends,’ ‘the brothers,’ and ‘part of the global Left’ who are ‘bringing about long term peace and social justice and political justice in the whole region’.[112]

And when this crude and reductive two-camp world view is applied to the Israel-Palestine conflict, Trotsky’s and Deutscher’s approach and sensibility is thrown out the window. In place of their awareness of the tragic, complex and unresolved national question, and their programme of consistent democracy and deep mutual recognition, the far Left, Trotskyists to the fore, has sought to teach the following to the rest of the Left:

(a) violent opposition to the Jewish people’s right to national self-determination, i.e. support for the destruction of Israel, any Israel;

(b) solidarity, sometimes critically, often uncritically, with the most reactionary regional actors, even the murderous antisemitic Islamist ones. Parts of the left now gloss the explicit, proud, canonical, and eliminationist antisemitism of such actors as heroic ‘anti-imperialist resistance’;

(c) a bullying culture ready to anathematise anyone who defends Israel’s right to exist;

(d) an ugly, demonising and dehumanising discourse of antisemitic anti-Zionism in which the Nazi analogy is ever-present, and which erases the border between legitimate criticism of Israeli government policy – of which they can be plenty, most of it made by Israelis themselves most days – and the repetition in new forms of the older antisemitic tropes, i.e. antisemitism ‘dressed up’ as anti-Zionism.

In a rich historical irony, the Left that wants to reject all that can learn much from… Leon Trotsky.

It can learn that antisemitism shape-shifts. Trotsky saw first hand how the core antisemitic demonology about the Jews could morph into new forms, including ostensibly left-wing forms, depending on the needs of the antisemites and the dominant intellectual language of the time. He saw that while antisemitism has a core message (or rumour, more like), that the Jews, collectively and in their essence, are not just the ‘Other’ but malign, the content of this perceived malevolence changes with the times and the needs of the antisemites. Trotsky had to stand against not just those antisemites crying ‘God-killers!’ or ‘untermenschen!’ but also also those targeting the ‘rootless cosmopolitans!’ and the ‘Jewish capitalists!’

When we understand this shape-shifting quality, is it really so hard to grasp that in the era of the first modern Jewish state, the dehumanising discourse of ‘anti-Zionism’ can sometimes play a similar role? That it can be the latest code word marking the Jew out for destruction? Is it not obvious that, sometimes, the Left is no longer engaged in legitimate ‘criticism of Israel’ but rather in demonisation, saying, in effect ‘the Zionists are our misfortune’, and with the same unbridled animus towards a spectral collective that the Nazis did when they said ‘the Jews are our misfortune’?

The Left can learn from Trotsky not only about the existence of left antisemitism but also about this fact: every time you find Left antisemitism you also find some left-wing Jews denying it exists and blaming the victims. The left-wing Jewish Stalin apologist B.Z. Goldberg, who said Trotsky was smearing Stalin and that there was no antisemitism in the Soviet Union, is a figure seen throughout the history of Left antisemitism. Realising this, perhaps the left might be a little less willing to reject a claim of Left antisemitism today just because some contemporary B.Z. Goldberg has issued a kosher certificate.

Above all, Trotsky can help the Left to come to terms with the existence of the nation-state of Israel, even as it campaigns for a Palestinian state alongside Israel. If Trotsky, writing before the Holocaust, thought that a Jewish national home would be needed even under socialism, if he could look forward to both Jews and Arabs each having their own rich and extensive spot under the sun, then isn’t there something terribly amiss with those who today – over 70 years after the Holocaust and the creation of a Jewish state, and in full knowledge of the grisly condition of today’s Middle East, where states fall, jihadi armies rise, minorities are routinely persecuted and eliminationist antisemitism is rife – propose to ‘Smash Israel’ as a ‘Nazi state’ and chant ‘Palestine, from the river to the sea!’ and wave their placards declaring ‘We are all Hezbollah Now’?

Today there are no hard borders between the different historic forms of antisemitism, ancient and modern, religious and secular, left-wing and right-wing. Ours is now a world in which the alt-right and the far Left, the Raed Saleh Islamists and the Stephen Sizer Christians, share the same tweets and memes, all depicting ‘Zionism’ as an all-powerful, malign, but hidden global hand, controlling politics, media and finance, starting wars, crashing economies, and bringing down Jeremy Corbyn. If you can’t see all that as a modern antisemitism then you are determined not to.

Trotsky is a resource for those on the Left who have had enough of all this. Reading about his long war against Jew-hatred, his bold revision of Marxism on the Jewish question, and his democratic vision of an accommodation between the two peoples, each enjoying their rich spot under the sun, Jews and Arabs both, in two homelands for two peoples, it is clear that the Old Man still has much to say to us.

References

* The following writings by Trotsky can be most easily accessed in Leon Trotsky, On the Jewish Question, Pathfinder Press, 1970. ‘Letter to “Klorkeit” and to the Jewish workers in France’ (10 May 1930); ‘Greetings to “Unser Kamf”’ (9 May 1932); ‘On the “Jewish Problem”’ (February 1934); ‘Reply to a question about Birobidjan’, October 1934); ‘Interview with Jewish correspondents in Mexico’ (18 January 1937); ‘Thermidor and Anti-Semitism’ (22 February 1937); ‘Appeal to American Jews menaced by fascism and anti-Semitism’ (22 December 1938); ‘Imperialism and anti-Semitism’ (May 1940).

Ackerman, Kenneth (2017) Trotsky in New York: A Radical on the Eve of Revolution, Counterpoint.

Carmichael, Joel (1972) Trotsky, Hodder and Stoughton, New York.

Carmichael, Joel (1973) Letter to Encounter, 11 January, in reply to Joseph Nedava.

Cliff, Tony (1987) ’55 Years a Revolutionary’, Socialist Review 100, July-August.

Cohn, Werner (1991) ‘From Victim to Shylock and Oppressor: The New Image of the Jew in the Trotskyist Movement’, in Journal of Communist Studies, Vol.7, No.1, March, pp. 46-68.

Crooke, Stan (2001), ‘The Stalinist Roots of left “anti-Zionism”, in Two Nations, Two States, Socialists and Israel/Palestine, a Workers Liberty pamphlet.

Deutscher, Isaac (1963) The Prophet Outcast. Trotsky 1929-1940, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Deutscher, Isaac (1967) ‘The Arab-Israeli War’, New Left Review 44.

Fine, Robert and Philip Spencer (2017) Antisemitism and the Left. On the return of the Jewish Question, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

Gerrard, Eve (2013) ‘The Pleasures of Antisemitism’, Fathom, Summer.

Geras, Norman (1986) Literature of Revolution: Essays on Marxism, Verso, London.

Geras, Norman (1998) The Contract of Mutual Indifference. Political Philosophy After The Holocaust, Verso, London.

Geras, Norman (2000) ‘Trotsky, Jewish Universalist’. The essay was written for the volume Les Juifs et le XXe siecle: Dictionnaire critique, edited by Elie Barnavi and Saul Friedlander and published by Calmann-Levy, Paris. The English translation appeared at Normblog on 2 September 2003. http://normangeras.blogspot.co.uk/2003_08_31_normangeras_archive.html#106251147555977590

Geras, Norman (2013) ‘Alibi Antisemitism’ in Fathom, Spring. https://fathomjournal.org/alibi-antisemitism/

Hirsh, David (2017) Contemporary Left Antisemitism, Routledge, London.

Hobsbawm Eric (1980) ‘Are we entering a new era of antisemitism?’, New Society, 11 December.

Howe, Irving (1978) Trotsky, Fontana, London.

Howe, Irving (1982) A Margin of Hope. An Intellectual Autobiography, Harcout Brace, New York.

Hudson, Martyn (2014) ‘Revisiting Isaac Deutscher’, Fathom, Winter.

Johnson, Alan (2000) ‘Democratic Marxism: The Legacy of Hal Draper’ in Marxism, the Millenium and Beyond, edited by Mark Cowling and Paul Reynolds, Palgrave, Basingstoke.

Johnson, Alan (2015) ‘An Open Letter to Jeremy Corbyn’, Left Foot Forward, 2015.

Johnson, Alan (2016) ‘Antisemitic anti-Zionism: the root of Labour’s crisis. A submission to the Labour Party inquiry into antisemitism and other forms of racism’. http://www.bicom.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Prof-Alan-Johnson-Chakrabarti-Inquiry-submission-June-2016.pdf.;

Johnson, Alan (2018) ‘In Defence of Ernest Erber’, Solidarity, 5 December, 2018.

Johnson, Alan (2019a) ‘Antisemitism in the Guise of Anti-Nazism: Holocaust Inversion in the United Kingdom during Operation Protective Edge’ in Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism: The Dynamics of Delegitimization, ed. Alvin H. Rosenfeld (Indiana University Press.

Johnson, Alan (2019b) ‘Denial: Norman Finkelstein and the New Antisemitism’, in Jonathan Campbell and Lesley Klaff eds. Unity and Disunity in Contemporary Antisemitism, (Academic Studies Press, Boston.

Julius, Anthony (2010), Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Antisemitism in England, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Kalmus, Jeffrey (2012) ‘Joshua Rubenstein on Trotsky’s Revolutionary Life’, in Harvard Political Review, 7 April. http://harvardpolitics.com/books-arts/joshua-rubenstein-on-trotskys-revolutionary-life/

Kessler, Mario (1994) ‘Leon Trotsky’s Position on Antisemitism, Zionism and the Perspectives of the Jewish Question’, in New Interventions, Vol.5 No.2.

Le Blanc, Paul (2012), ‘Trotsky – truth and fiction’, International Socialist Review, No. 82.

Mandel, Ernest (1995) Trotsky as Alternative, Verso, London.

Matgamna, Sean (1988) ‘Anti-Semitism and the Left: An Open Letter to Tony Cliff’, in Workers Liberty No.14, pp. 11-12.

Matgamna, Sean (1996) ‘Two states for two peoples’, Workers Liberty, July, pp.15-17.

Matgamna, Sean (1998) The Fate of the Russian Revolution. Lost Texts of Critical Marxism Vol.1., Workers Liberty, London.

Matgamna, Sean (2001) ‘Marxism and the Jewish Question’ in Israel-Palestine: Two Nations, Two States, Alliance for Workers Liberty, London, pp. 19-22.

Matgamna, Sean (2015) The Two Trotskyisms Confront Stalinism, Workers Liberty, London

Matgamna, Sean (2017) The Left in Disarray, Workers Liberty, London.

Matgamna, Sean (2019) ‘Labour’s anti-Semitism crisis: an open letter to Jeremy Corbyn’, Solidarity 497, 26 February.

Molyneux, John (1981) Leon Trotsky’s Theory of Revolution, St Martin’s Press, New York,

Nedava, Joseph (1971) Trotsky and the Jews, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia.

Nedava, Joseph (1973) ‘Trotsky as Jew’, Commentary, 11 January.

O’Malley, J.P. (2016) ‘Trotsky’s day out: How a visit to NYC influenced the Bolshevik Revolution’, The Times of Israel, 19 September.

Rubinstein, Joshua (2011) Leon Trotsky: A Revolutionary’s Life, Yale University Press.

Segal, Ronald (1979) The Tragedy of Leon Trotsky, Hutchinson, London.

Service, Robert, (2009) Trotsky. A Biography, Pan Macmillan, London.

Sternhell, Zeev (2010) ‘In Defence of Liberal Zionism’, New Left Review, 62.

Traverso, Enzo (1994) The Marxists and the Jewish Question. The History of a Debate 1843-1943, Humanities Press, New Jersey.

Traverso, Enzo (1999) Understanding the Nazi Genocide. Marxism After Auschwitz, Pluto, London.

Trotsky, Leon (1934) On the Jewish Problem. Class Struggle, Official Organ Of The Communist League Of Struggle (Adhering to the International Left Opposition), Volume 4 Number 2, February 1934. https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1934/xx/jewish.htm

Trotsky, Leon (1940) ‘The Imperialist War and the Proletarian World Revolution: The Manifesto of the Emergency Conference of the Fourth International’, in Writings of Leon Trotsky 1939-40, Pathfinder, 1973.

Trotsky, Leon, (1975) The Struggle Against Fascism in Germany, Pelican, London.

Trotsky, Leon (1975) My Life, Penguin, London.

Trotsky, Leon (1970) On the Jewish Question (a collection of 8 articles and interviews), Pathfinder, New York.

Wistrich, Robert S. (1976) Revolutionary Jews from Marx to Trotsky, George G. Harrop, London.

Wistrich, Robert S. (2010) ‘Trotsky’s Jewish Question’, Forward, 18 August.

Wistrich, Robert S. (2012) From Ambivalence to Betrayal. The Left, the Jews and Israel, University of Nebraska Press, Nebraska.

Wistrich, Robert S. (2010) ‘Trotsky’s Jewish Question’, in Forward, 18 August.

[1] No British Marxist has done more to bring Trotsky’s late thinking to the attention of the contemporary left, to apply it to the present day, and to educate a layer of left-wing activists and intellectuals to think about Israel and Palestine outside the confines of Stalinist demonology than Sean Matgamna. See Matgamna 1996, 2001, and 2017: 231-244, 306-317.

[2] This essay was first presented as a paper to the Pears Institute for the Study of Antisemitism conference ‘Zionism and Antisemitism’, 24-26 May 2017. Thanks to Eve Garrard, Martyn Hudson and Stephen de Wijze for feedback on this version.

[3] For 19th century Marxists, ‘the Jewish Question’ meant roughly ‘the antisemitism question’. Why were Jews excluded and oppressed and what should be done about that? How can Jews be brought into citizenship? Relatedly, are the Jews a people (and if they are, do they have the right to a state of their own)? Or, are they ‘only’ a religious minority, owed only the rights of a religious minority? However, Robert Fine and Philip Spencer (2017) have pointed out that the expression ‘Jewish Question’ can carry the implication of something more disturbing, especially in the move from question to answer. All too often, they suggest, asking ‘the Jewish question’ leads to answers vitiated by three dubious assumptions: that what we should be trying to do is identify the harm Jews inflict (the harm being assumed), explaining this harm (finding the bit of Jewish nature or being that explains why they inflict this harm), and then finding a solution to that harm (from civic rights to genocide). I share their concern.

[4] See ‘The Messianic Materialism of Walter Benjamin’ in Traverso 1994: 167-187.

[5] Deutscher 1963: 369; Wistrich 2012:399.

[6] Cohn 1991.

[7] Traverso 1994:202. He also praises the contributions of the Judeo-Marxists, including Borokhov, and writers from the Frankfurt School, for stressing the protean character of antisemitism, its modernity, and its unconscious as well as conscious wellsprings. While this essay focuses on Trotsky it does not claim he was the only socialist, or even the only Bolshevik, to make a contribution to the understanding of antisemitism. For the latter, see Brendan McGeever’s forthcoming monograph The Bolsheviks and Antisemitism in the Russian Revolution (Cambridge University Press, 2019). The political point is that Trotsky is a credible messenger to a large portion of today’s ‘left that has lost its way’. Hence my focus.

[8] Mandel, 1995: 148, 152.

[9] Service 2009: 481.

[10] Traverso 1994:201-2.

[11] Traverso 1994:204.

[12] Traverso 1994:234.

[13] Mandel 1995: 147.

[14] Traverso 1994:236.

[15] Traverso, 1994: 235, 233.

[16] Traverso points out that the implications of Zionism for the Arabs of Palestine were scarcely registered until much later, except perhaps by Karl Kautsky.

[17] Traverso 1994: 232-33.

[18] Trotsky, ‘Interview with Jewish Correspondents in Mexico’, 1937.

[19] Mandel 1995:107.

[20] Trotsky, quoted in Nedava 1971:113.

[21] Trotsky, ‘Interview with Jewish Correspondents in Mexico’, 1937.

[22] Trotsky, ‘Thermidor and Antisemitism’, 1937.

[23] Deutscher 1963, 369, n.1. Rubinstein’s recent study of Trotsky was commissioned as part of Yale’s Jewish Lives series, yet it misses this late but radical rethinking of the Jewish question by Trotsky, more or less completely.

[24] Traverso 1994: 228.

[25] Traverso 1999:1.

[26] Geras 2013.

[27] Carmichael 1973. Ernest Mandel notes that in the young Soviet Republic, ‘it was only the Jews that were declared a nationality without having their own territory. Although they were numerically larger, territorially more concentrated and characterised by a higher level of cultural homogeneity then many of the other nationalities that were given an autonomous territory or autonomous republic, the Jews were not granted the right to their own state’ (1995: 147).

[28] Traverso 1999:3.

[29] Travero 1994:9.

[30] Traverso 1994:9.

[31] Traverso 1994:140.

[32] Trotsky, ‘Interview with Jewish correspondents in Mexico’, 1937.

[33] Trotsky 15 June 1940, in Writings, 1939-1940, p. 287.

[34] Trotsky, ‘Interview with Jewish correspondents in Mexico;, 1937; ‘The Jewish Problem’, 1934; ‘Thermidor and Antisemitism’, 1937.

[35] Deutscher 1963: 369.n1.

[36] Wistrich 2012. 399.

[37] Trotsky, ‘Appeal to American Jews menaced by fascism and antisemitism’, 1938.

[38] Trotsky, ‘Thermidor and Antisemitism’, 1937.

[39] Trotsky, ‘Interview with Jewish correspondents in Mexico’, 1937

[40] Trotsky ‘On the Jewish Problem’, 1934.

[41] Service 2009: 199.

[42] Nedava, Joseph, 1971: 28.

[43] Trotsky ‘Thermidor and Antisemitism’, 1937.

[44] Nedava 1971:122.

[45] Mandel 1995:148-9.

[46] Nedava 1971: 5, 69. It is surprising then, that Robert Wistrich, after praising Trotsky for breaking from Marxist orthodoxy, damns him for remaining ‘imprisoned within the straitjacket of Marxist dogma’; for viewing antisemitism as only a symptom of capitalist crisis (400), and for having an ‘unconscious Jewish complex’ (whatever that is). Although Wistrich’s contribution to our understanding of left antisemitism was huge, I do not find his argument persuasive in this case for two kinds of reasons: it is not accurate and it is an example of a wild psychoanalysis.

Trotsky did not reduce antisemitism to a symptom of capitalist crisis. He posited a connection between the rise of antisemitism in Germany and severe capitalist crisis in Germany (See Geras 1998:72). And he was right to do so. Trotsky is valuable today not least as a corrective to the tendency today to simply equate anti-capitalism and antisemitism, treating any half-radical economic reform proposal as if it were the antechamber to a pogrom. Geras’s warning is still valid: ‘the link between capitalism and barbarism is not to be lightly shrugged aside’ (1998:169).

Wistrich quotes approvingly Chaim Weizmann’s claim that Trotsky thought ‘immoral any focus on the sufferings of Jewry’, but writes a few lines later of Trotsky’s ‘impassioned and deeply felt’ attack on antisemitism, concluding that ‘no other Marxist revolutionary matched him’ (386-7). So which was it?

About Trotsky’s conduct after 1917, Wistrich claims that once his ‘messianic hopes’ were confirmed by the revolution he dismissed ‘such trifles as the sufferings of Jewry,’ a claim which is demonstrably untrue. Wistrich then passes on without comment a smear from a ‘Zionist Hebrew writer’ that when it came to Jewish suffering, ‘Trotsky is more to blame than a thousand Denikins’. But Denikin was an energetic pogromist and Trotsky risked much, not least his own life, to stop those pogroms (393).

Wistrich puts Trotsky on the couch and delivers himself of what Freud would have called a ‘wild’ psychoanalytic reading of his subject. The analysand Trotsky is laid bare by the analyst Wistrich, and after one session, so to speak. We are told of Trotsky’s ‘mocking eyes’, ‘aristocratic hauteur’, ‘blind fanatical devotion’, ‘unconscious Jewish complex’, and ‘latent anti-Jewish prejudices’ (2012:401). For example, Wistrich claims to find in Trotsky’s political criticism of the Menshevik Martov, an unconscious antisemitic assault upon the Jew Martov. He reads Trotsky’s distinction between Bolshevik intransigence and Menshevik wavering as a proof that Trotsky ‘never fully succeeded in shaking off [the] shadow Jew in his own unconscious’ (2012:411). It seems Wistrich’s access to Trotsky’s unconscious, which surely died along with his body in August 1940, was total.

Wistrich even reads Trotsky’s fight against Stalin’s antisemitic attacks on his son as an expression of Trotsky’s own ‘unconscious antisemitism’! He suggests that when Trotsky objected to the Soviet press describing his (soon to be murdered) son Leon Sedov as ‘Leon Bronstein’, this was an example of Trotsky ‘exposing his own unconscious “Jewish” complex’. (2012:401). In fact, Trotsky was exposing not his own but the antisemitism of the Stalin regime. Is the work of unmasking the running dog Leon Trotsky never done?

[47] Rubinstein, interviewed in Kalmus 2012.

[48] Nedava, 1971:49.

[49] Rubinstein, 2011:31.

[50] On the psychological benefits of antisemitism to antisemites see Garrard 2013.

[51] Rubinstein 2011 :52, 45.

[52] Nedava 1971: 60-61.

[53] Geras 1986: 249.

[54] Rubinstein, 2011:61.

[55] For Trotsky’s writings on the Beilis Trial, see Rubinstein 2011.

[56] Johnson 2015.

[57] Segal 1979:105.

[58] Rubinstein, 2011, 65.

[59] Rubinstein 2011: 65.

[60] Segal 1979:102.