Karolina Placzynta is a researcher for the Decoding Antisemitism project at the Centre for Research on Antisemitism, Technical University Berlin. She explains the methodology and the main findings of a recent report into antisemitism found in the comments boxes of the mainstream media in the UK, France and Germany.

With the first anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine just passed, we are seeing many analyses of how the war has affected the lives of people in Ukraine, Russia and – albeit less directly – the UK over the past twelve months. Examples of its impact are many and complex, but one that probably does not immediately come to mind is a shift in antisemitic hate speech in British online media. And yet, there is compelling evidence that mainstream media coverage of the invasion has boosted the levels of antisemitism – especially Israel-related – in online comments sections, and that they may be particularly high in the UK.

When the news of the invasion broke at the end of February 2022, it soon became clear that the issue would dominate the media in the UK and Europe. To researchers of online antisemitism, it was also quickly obvious that it would provide ample material for analysis. In the regularly published discourse reports prepared by our team at the Decoding Antisemitism project (based at the Centre for Research on Antisemitism at TU Berlin and funded by the Alfred Landecker Foundation) we analyse thousands of online reactions, to this and other events which have triggered a spike in antisemitism levels in the comments sections in the UK, as well as France and Germany.

Our recent report showcases findings from two internationally covered events, the invasion of Ukraine and the eruption of terrorist violence in Israel in the spring of 2022. We also take a closer look at several country-specific cases from the past months: in the UK, the writer Sally Rooney’s boycott of Israeli publishers; in France, the Pegasus spyware affair; and in Germany, the controversies surrounding the singer Gil Ofarim and the reactions to some of the artwork on display at the documenta 15 exhibition. This may seem like an eclectic list of contents – it spans three countries, a few dozen news outlets, hundreds of online comment threads, and a range of topics from culture, to technology, to foreign politics – but it turns out to be rather coherent when it comes to the results of the analysis. What the events have in common is not just the fact that they have all generated antisemitic commentary, but also that most of the antisemitism revolves around the themes of delegitimisation, demonisation, and dehumanisation of Jews and Israel, either by openly rehashing classic tropes or by employing new strategies. Some comments imply antisemitic meaning through creative use of words, emoticons or punctuation, others look innocent on the surface because they use irony or are phrased as a question. Many simply acquire an antisemitic undertone only in the context of the thread. Our research shows how antisemitism can attach itself to virtually any issue, reach a broad spectrum of audiences, and lurk not just in the dark corners of the internet but in plain sight.

Methodology

To prepare a report, we spend several months gathering and analysing online comment threads appearing under articles posted on mainstream news websites in the UK, France and Germany, or on their official social media accounts (mainly Facebook and Twitter pages), across the political spectrum. Each comment needs to be carefully considered and categorised. If it is deemed antisemitic, we match it with a specific concept, trope or stereotype from a detailed set of guidelines we have developed. There will often be a linguistic category as well – metaphor, allusion, joke, wordplay, to name a few of those which make antisemitism harder to detect. The focus is on the comment and its context, never on the identity of the web user who typed it, and we presume innocence whenever any doubts about the possible interpretation come up. We also make sure to separate fair and justified critique towards individuals, groups or governments from exaggerations and generalisations extended to all Jews or Israelis, and to the entire State of Israel.

Findings

Sally Rooney’s Boycott: ‘Human with a conscience’ vs. ‘subhuman’

When, in October 2021, the popular Irish novelist Sally Rooney announced that she would not grant an Israeli publisher translation rights to her most recent novel, UK media reports of her decision prompted readers to take a side and express their opinion in the comments sections. She had voiced her support for the Palestinians in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and for the cultural boycott of Israel, and so – predictably – in many of the nearly four thousand comments we analysed, the opinions turned out to be a critique of Israel, and in 12 per cent of the cases the critique turned into antisemitism. Such comments praised Sally Rooney as a ‘human with a conscience’,[1] and her supporters as those who could never ‘take the side of people who think routinely murdering children and other civilians is justified’. By extension, anyone questioning Rooney’s decision was typically deemed at best wrong, and at worst immoral, ‘subhuman’ and a liar. Israel itself was painted as ‘genocidal’ and ‘oppressive’. Others referred to Israel as ‘illegal’ or an ‘apartheid entity’, and to Jews as a lobby attempting to wield power or privilege. Whether consciously or not, such comments reiterated a whole host of well-documented classic antisemitic tropes which portray Jews as murderous, inhuman, or simply evil, Israel as illegitimate, and both of them as part of a network with mysterious amounts of global influence.

Violence in Israel: ‘Not humans’

A few months later, in the first half of 2022, UK media covered several violent attacks on Israeli civilians in the cities of Beersheba, Hadera, Bnei Brak, Tel Aviv and El’ad. The news set off another wave of the same debate in the comments sections: the attacks took place in Israel, three of the perpetrators were reported as Palestinian, and in the other two cases Hamas representatives apparently praised the attacks. This time, 17 per cent of the three thousand UK comments we analysed were antisemitic. Most of these agreed with, or even celebrated the attacks – through words as well as memes and emojis, with comments such as ‘made my day’. Some went to the trouble of justifying their applause and admiration for the attackers with the argument that the civilian Israeli victims were, in fact, aggressors – if only by virtue of their nationality. The comments seemed to dismiss their humanity or individual identity, instead labelling them as ‘colonisers’, ‘potential murderers’, ‘Zionists not humans’, and claimed that ‘there is no innocent person in Israel’. Meanwhile, the perpetrators were hailed as ‘heroic’, and sometimes compared to Ukrainians resisting the Russian invasion.

War in Ukraine: Dubious analogies and shifting of the blame

It is perhaps inevitable that war or conflict narratives quickly develop into tales of relatable heroes fighting against loathsome villains, leaving little space for complexity. It also seems that when discussing one military action, another is brought in for comparison, however inaccurate or ahistorical this may be, and comparisons between Ukraine and Palestine proved to be a low-hanging fruit. Early on in the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s attempts to mediate peace talks between the two countries got considerably more attention than general reports of mediation by various other parties. The comments sections mustered some support for Bennett, but also plenty of sarcasm and indignation at his efforts. Comments painted a dark picture of Israeli officials: ‘Devils with blood on their own hands cant play peacemakers while running an apartheid state’, or claimed that Israel gets a free pass from the international community: ‘Mr Bennett is ideally placed to broker peace. He can argue that Israel is occupying Palestinian territories but nobody makes any fuss so the world needs to accept that Russia can occupy Ukrainian territories in the same manner’.

Lavrov and ‘Hitler’s Jewish Origins’: Cue Conspiracism

Two months later, the simmering debate boiled over once more after Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov alleged that Hitler had Jewish origins. The old conspiracy theory proved too tempting for the internet. Some 16 per cent of comments agreed with it – either outright, or by offering arguments and conclusions, such as ‘Hitler did all these atrocities to Jews to prove that he is German’. By framing it as historical fact, they neatly closed the circle of blame claiming that a Jew is to blame for what was done to Jews, essentially absolving any other parties from antisemitism. Yet others saw an opportunity to repeat more conspiracy fantasies: ‘That’s why I always say WW11 was a planned war. The Jewish elite with their allies stage[d] the war…’.

Nazi Analogies and Holocaust Trivialisation

Another analogy within easy reach was that between modern-day Russia and Nazi Germany. We did not need to wait for Godwin’s law (according to which in every online discussion someone will eventually compare someone else to Hitler or to Nazis, if the discussion goes on for long enough) to come into play. Instead, references to Nazism made an appearance in the rhetoric of both Russian and Ukrainian leadership almost from the start. In the first few weeks of the invasion, the UK media reported on Russian politicians framing it as an effort to ‘de-Nazify’ Ukraine. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky accused the Russian government of ‘deporting Ukrainians to concentration camps’ and of ‘bloody reconstruction of Nazism’.

But similar comparisons were also made by British journalists and politicians, including the Defence Secretary Ben Wallace, and reverberated throughout online comments. They raced to give more and bolder examples of the supposed Nazi-like behaviour of both sides: ‘Putin putting up Russian language road signs and Russian statues sounds like the kind of reprogramming that Hitler engaged in’, ‘What they’ve done already – illegal invasion, seizing territory, killing of civilians, rape – is more than enough to qualify as nazi, comrade’, ‘Last time I’d checked Ukraine was celebrating Nazis and Azov Nazi batallion was part of Ukraine armed forces!?’.

When undeniably horrific reports of wartime atrocities appear in the media, some confirmed and some not, an analogy with Nazism is an easy one to make. It is a common point of historical reference understood by all and a byword for ultimate cruelty, at least in this part of the world. But, while the comparison in itself might not always be antisemitic, one of the effects of using Nazi analogies is that the original meaning can become diluted and the Holocaust relativised or distorted, seemingly just one in a series of comparable events throughout history, instead of recognising its unique character and scale.

The ‘Ukrainetransport’

Perhaps the most telling example is an article in The Guardian describing plans to organise a ‘Ukrainetransport’ for families fleeing the invasion of Ukraine, an initiative by a British rabbi. Although the text simply said help was to be offered to Ukrainians trying to escape to safety, some online comments were quick to assume that it was intended only or primarily for Ukrainian Jews, echoing the damaging stereotype that Jews are above all loyal to their own. The article made no mention of Israel or Palestine either, but there were still those who managed to make an unprompted connection: ‘why isn’t the same proposal offered for the Palestinians whose homes and land are being destroyed by the people who share your faith and ethnic[ity]? … Selective humanism’. Holding British Jews responsible for any action, or inaction, in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is at best a misconception, confusing Jews (not all of whom are Israeli) with Israelis (not all of whom are Jewish) and detracting from the charitable intentions of the initiative.

Why is Antisemitic Online Discourse Higher in the UK?

In percentage terms, levels of antisemitism for the events we discuss in the report tended to be higher in the comments from British sources, and lower for France and Germany. When French media broke the news that Pegasus spyware, developed by the Israeli company NSO group, had been used by the Moroccan government to collect information on the likes of President Emmanuel Macron, only five per cent of the online comments contained antisemitism. In Germany, reports of the singer Gil Ofarim allegedly being turned away by hotel staff because of his Jewish identity generated 8.5 per cent of antisemitic comments, and the documenta 15 art exhibition in the German city of Kassel, which hosted a controversial painting – seven per cent. (Recall that in the UK, 12 per cent and 17 per cent of responses to the Sally Rooney story and the violence in 2022 were, respectively, antisemitic.)

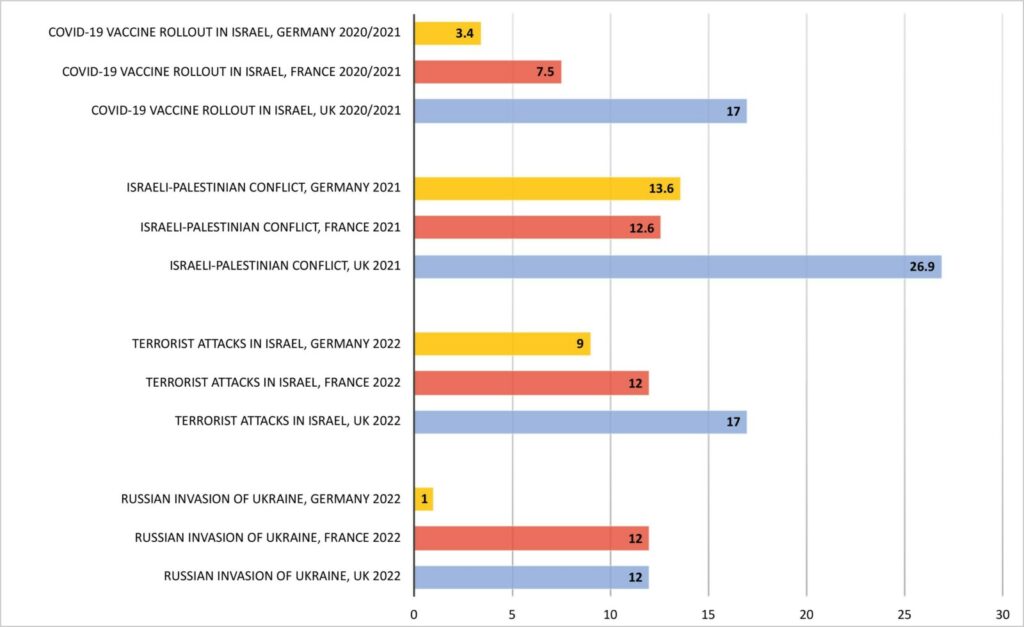

It is difficult to compare such different topics and extricate them from their sociocultural contexts without being accused of cherry picking, and to draw overarching conclusions from just a few events. We can, however, look at the findings of all the reports we have published so far to see if any tentative patterns emerge specifically from those events which were analysed across all three countries. In such comparisons, UK results are always in first place, with the exception of one first-place tie with France. Sometimes the contrast is particularly stark: in the first half of 2021, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict triggered a particularly high level of antisemitic comments in the UK (nearly 27 per cent) – twice as high as in France or Germany; this dramatically high figure seems to correspond with the CST report from 2021[2] which noted a sharp increase of antisemitic incidents in the UK in May that year and linked it to the escalation of the situation in Israel and Palestine. The level of antisemitism was also considerably higher in UK comments posted under media reports of the Covid-19 vaccine rollout in Israel in late 2020 and early 2021 than in their French and German counterparts (17, 7.5 and 3.4 per cent respectively). The most recent report follows this pattern: the invasion of Ukraine triggered the same results in the UK and France (12 per cent each), but just 1 per cent in Germany; for the attacks in Israel, UK data was again in first place with 17 per cent, France in second with 12, and Germany in third with nine.[3]

Percentage of antisemitic comments in reaction to mainstream media reports in 2020-2022, by country. (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

The reason for the higher level of antisemitic comments in the UK discourse is most likely an accumulation of several factors that statistics alone cannot explain. Although media platforms already use moderation, a considerable amount of implicit antisemitism seems to pass under the radar, harder to detect than the obvious insults, slurs or threats we usually associate with hate speech, and it is possible that online content moderation is managed differently for each of the three languages. It may also have something to do with the way mainstream media in each of the three countries set their agenda and the style in which they report the news, or the way freedom of speech is understood and exercised in the comments. It seems that web users in German comments sections are especially wary, which is understandable considering the history of the Nazi regime and the effort made by subsequent German governments to move on from it.

Agenda for Change: Education and Better Moderation

While our research provides some answers about antisemitic hate speech online, it also raises questions. Is it possible to make consumers of media content more aware of these and other forms of contemporary antisemitic speech? Perhaps, but reaching them is by no means straightforward. The online edition of The Guardian, the BBC News Facebook page, or other British news outlets are often accessed by English-speaking readers from all over the world, which potentially blurs the lines of what UK discourse around antisemitism is. It also makes for a potentially vast audience, perhaps too varied to effectively reach with an educational message about antisemitism and hate speech. This is made even more complicated by the presence of bots in comments sections, or the fact that debates on controversial issues help media companies boost website traffic and therefore their revenue. On a positive note, there is plenty of counter speech in the comments sections already, calling out antisemitism and increasing in direct proportion to the levels of antisemitism. It is a great shame that it can turn ugly, too. Some of Sally Rooney’s critics made xenophobic comments about her nationality, and misogynistic remarks about Rooney herself; many of the pro-Israeli comments are heavily Islamophobic or racist.

Could hate speech comments completely disappear from news websites? By some standards, the proportion of antisemitic comments we have detected may already seem low, although this is partly because we err on the side of caution in our analyses. On the other hand, they are taken from mainstream media outlets, where they have clearly slipped through moderation as human and automated content moderators struggle to detect some types of hate speech, particularly the implicit, contextual kind. Apart from sharing our conclusions with a wide audience of interested readers, we collaborate with data science and machine learning specialists from HTW Berlin, King’s College London and HateLab in Cardiff, who are using our research to build sophisticated algorithms that may eventually be able to imitate human understanding of nuanced, implied meaning more closely, and potentially make the job of both content moderators and researchers much easier.

Bibliography

Becker, Matthias J. 2019, ‘Projections of National Guilt as a form of Antisemitism in German and British centre-left Milieus: An analysis of readers’ comments in Die Zeit and The Guardian as a setting for antisemitism and historical relativisation’, European Journal of Current Legal Issues, 25(1).

Gold, Dore 2011, ‘The Myth of Israel as a Colonialist Entity: An Instrument of Political Warfare to Delegitimize the Jewish State’, Jewish Political Studies Review, 23: 84–90.

Ozalp, Sefa et al. 2020, ‘Anti-Semitism on Twitter: Collective Efficacy and the Role of Community Organisations in Challenging Online Hate Speech’, Social Media + Society, 6(2): 1–20.

[1] All quotations taken verbatim from online comments sections on websites and/or social media accounts of BBC News, Daily Mail, Daily Express, Financial Times, The Guardian, The Independent, The Telegraph and The Times. For more detailed information on the sources, see Decoding Antisemitism: An AI-driven Study on Hate Speech and Imagery Online. Discourse Report 4.

[2] Community Security Trust 2022. Antisemitic Incidents. Report 2021: 16-20

[3] Data from an upcoming report will be available on its publication in April this year. In it, we analyse reactions to antisemitic statements made by Kanye West and incidents at the 2022 FIFA World Cup; it also covers some new results in the field of AI.