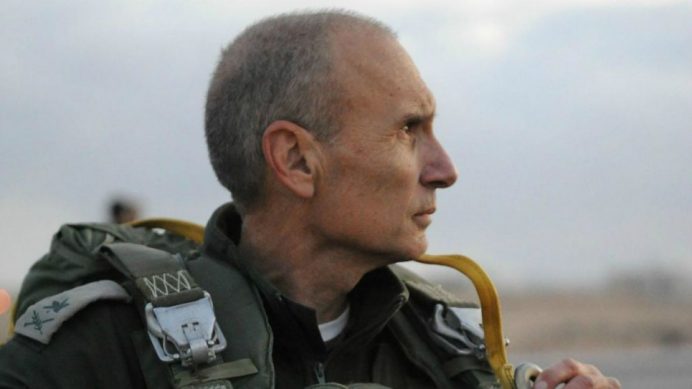

Maj. Gen. (res.) Gershon Hacohen served in the IDF for 42 years, commanding troops in battle on the Egyptian and Syrian fronts, and filling positions as a Corps commander and commander of the IDF Military Colleges. In 2005 he was the officer in charge of implementing Israel’s disengagement from Gaza. Hacohen is currently a researcher at the Begin Sadat Centre for Strategic Studies (BESA). In his article, Hacohen disagrees with the accepted wisdom regarding the effectiveness of barriers, suggesting that there is no substitute for troops on the ground and cautioning against an Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank. He ultimately concludes that a Palestinian state would inherently undermine Israel’s security.

The purpose of security: the priority of values and strategic direction

Discussing security is actually comprised of two separate basic questions. One is how to defend a country’s existence, and is made up of primarily technical components, such as the location or height of a barrier and is intended for experts. However, a core question that precedes it is intended for philosophers, prophets and leaders and is based on one’s values and world view. This revolves around the issue of what a country is defending; in other words, the essence and purpose of its existence. Nations should be constantly trying to maintain equilibrium between these two sets of considerations.

One example of the ‘values’ question which surrounds the purpose of a nation’s existence took place in April 1948. The situation for the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine, was dire. The Negev and communities in the north were under siege while convoys were unable to reach Jerusalem and Gush Etzion. Faced with these threats, David Ben-Gurion decided to focus the main operational effort of his forces on Jerusalem. This decision was not due to the technical recommendations of his military experts but was influenced by his world view as a Jew regarding the city’s centrality, and the historical Jewish oath reflected in psalms ‘not to forget Jerusalem’.

A leader should not ignore what the experts say, but ultimately his role is to be influenced by values in order to create equilibrium between these two conversations. There is no equation of how to do this.

Ultimately, one can’t discuss how to defend Israel’s existence without first touching on the conversation of what it is being defended for. We Israelis are not simply here in order to live securely and promises by US presidents that America will always protect us do not impress me. If all I want is security, I might as well bring the entire population to Tel Aviv and build a huge fortress. Alternatively, I could move to Palo Alto, which has a better quality of life and greater opportunities. A US general who told me that ‘at the end of the day everyone wants the same things – restaurants that are open until midnight and kids that can get safely to school’ deeply misunderstands me – because I can get all of that in New Jersey.

Jews in Israel may have swapped the threat of pogroms in Kishniev for the threat of Iranian nukes. But when discussing security it’s important to emphasise that something beyond pure security exists, which lies in the realm of values and vision. I believe that the essence of Zionism is to live in the Land of Israel, the land of our forefathers. We didn’t just come here for a Jewish majority or sovereignty but also simply to live in the land.

Boots on the ground and the problem with fences

Some say that Israel’s West Bank security barrier prevents terror attacks on population centres. But when the Palestinians are beyond a fence it actually creates a worse security situation. The fence is a closed system; protecting it involves routine patrols and cameras. Every mechanical system has points that can be bypassed (in fact a reason for the delay in building the security barrier in the south Hebron hills is that parts of it have been stolen). An enemy that understands such a defensive system can get around it.

I prefer a more open, flexible, dynamic-movement security activity. Such a system would facilitate creativity and surprise, which would make it impossible for the enemy to predict the movements of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). It may involve constantly changing one’s pattern of activity or altering the location of checkpoints (and some days not having any at all). But ultimately it encourages the IDF to initiate and prevents it becoming too passive.

Many Israelis believe that if we erect a fence the problem would suddenly vanish. But the problem on the other side often gets worse. For example, since leaving Gaza in 2005, Israel no longer has an effective intelligence presence operating on the ground. Rather than protecting Israel, the fence around Gaza actually restricts Israeli operations. The withdrawal of an Israeli presence from Gaza and reliance on the barrier shows that the moment Israel builds a fence and ceases to operate on the other side it allows the Palestinians to create a well-structured military force including battalions, brigades, and command and control headquarters, which can only be destroyed in a war. Meanwhile, if Israel receives information about a bomb laboratory in the West Bank, it can simply enter the territory with two jeeps and arrest the suspected operatives without starting a full blown conflagration. Israel’s presence on the ground in the West Bank also makes it harder for Hamas to organise itself there. A Hamas activist based in Hebron is rarely in touch with his commander because they have been forced to create heavily compartmentalised units where members and operations are only revealed on a need-to-know basis. The moment Hamas begins to plan an attack in the West Bank the IDF can take steps to prevent it. In Gaza however, Hamas is far more organised – it has a headquarters that can plan, train for and carry out attacks against Israel.

The current reality in the West Bank lies somewhere between war and peace. It is not stability but closely resembles the form of life the entire Middle East is experiencing. The daily friction stemming from the current situation in the West Bank is better for Israel than two alternative scenarios, namely temporary quiet in Gaza followed by serious wars which cause significant damage to both sides (think of Operation Cast Lead in 2008-09, Operation Pillar of Defence in 2012 and Operation Protective Edge in 2014); or a withdrawal from the West Bank which would inevitably be followed by Israel having to recapture the territory during an emergency. Here it should be noted that even Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza did not provide the country with international legitimacy for defending itself against subsequent rocket attacks.

Yet in Gaza today there is a closed fence and everything has become binary. The entire area by the border is now built up while the fence around the Strip means that everything near the border is well fortified, thus making it harder for the IDF to attack. Hamas knows exactly where the IDF will enter from. Security as dynamic movement has been completely lost. Instead, the IDF is required to rely on air power. This situation – which we do not have in the West Bank because Israel still controls it – is the big disadvantage of what some on the Israeli political left call the ‘we’re here they’re there’ approach.

In 2006 I worked alongside an American general in order to determine how an army could maintain surveillance without having a physical presence on the ground. The Americans initially believed that intelligence and operational superiority, coupled with Remotely Piloted Vehicles (RPVs) that could strike from afar, would be enough to create dominance without the need to put boots on the ground. But the opposition was quick to adapt and went underground. This happened to Israel in Operation Protective Edge. Hamas’s leaders in Gaza disappeared and managed to neutralise Israel’s superiority. Moreover, nowadays, most of Hamas’s rockets in Gaza are stored underground and Israel finds it difficult to defend itself against rockets launched from Gaza towards Ben Gurion International Airport and Tel Aviv.

Securing the Jordan River

One of the big challenges emanating from Gaza is weapons smuggling. Even the Egyptians – who are in the midst of a battle with ISIS in Sinai – have been unable to fully prevent this phenomenon. One Rocket Propelled Grenade (RPG) entering the West Bank would require changing the IDF’s entire modus operandi. Israel would no longer be able to enter refugee camps in trucks and would be forced to rethink how it buses children to school.

The only way to prevent smuggling into the West Bank is to control the Jordan valley and implement inspections. This has to be done by Israel; we do not want Americans dying in order to protect us. Yet in order to securely hold the Jordan Valley, the IDF also needs to maintain a presence further to its west, where the mountain ridge along the eastern watershed of the Samarian and Judean Mountains is located, and which includes Nablus, the Jewish settlements of Elon Moreh and Itamar as well as the Alon Road. Holding the Jordan Valley without simultaneously controlling the mountain range would not allow the IDF to properly defend itself, nor provide it with minimal strategic depth.

Before the Gaza disengagement, then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon debated whether to maintain a residual IDF presence along the Philadelphi Corridor (the strip of land between Gaza and Rafah in Egypt) in order to prevent smuggling. The reason he ultimately decided against it was because, similar to the situation in the Jordan Valley, the corridor was too narrow to provide sufficient protection to the soldiers who would have been stationed there.

The changing face of war and the necessary role of settlements

In his book The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World, British General Rupert Smith describes a new paradigm of conflict which he calls ‘war amongst the people’. Rather than warfare between uniformed armies on a battlefield, Smith argues that the defining character of conflicts is that they are now increasingly fought between parties that are part of, and amongst, the civilian population.

Traditional experts disagree with me that anything has significantly changed in warfare. But this is like the difference between theatre in Greek times and 21st century cinema. One can argue that they are both ‘theatre’ but the two are completely different, with significant numbers of new ‘tricks’ one can now bring to the stage. And rather than the more static classic separation between defensive and offensive operations in the works of Clausewitz, a better model to deal with this new type of warfare is the hybrid dynamic movement model.

This so called post-modern warfare is reflected in separatist fighting in Donetsk in Eastern Ukraine as well as in other areas of the Caucasus where civilians are on the front lines. Comparable aspects to this type of ‘in and amongst the civilian population’ are apparent in Judea and Samaria. The IDF only has 10,000 troops in the West Bank, but the mass presence needed for security is in fact provided by the presence of Israeli civilians. Without them Israel would be unable to ensure its security. In fact, before disengagement from Gaza the Israeli settlements – in the north, centre and south – helped Israeli security by allowing Israel to better defend itself from any attacks originating from Gaza.

The clash between Palestinian sovereignty and Israeli security

The entire spectrum of fulfilling the Palestinians’ national aspirations clashes with Israel’s security because a sovereign Palestinian state would endanger Israel. Even in a situation where a Palestinian government would try and maintain a peace agreement, there would still be other rejectionist groups that try to undermine it. One mortar hidden in a car that could be launched towards Ben Gurion International Airport would be a disaster, and this scenario is a real possibility even if a Palestinian government tries to prevent it. Moreover, today anyone can build home-made weapons with dual-use civilian materials such as iron pipes and chemicals, whilst using instructions found on the internet. Even a cell phone can be used for this purpose, as the Americans saw in Iraq with the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

Separation is not the answer

The main idea behind the two-state solution is creating a binary order where two separate areas exist with no interaction between them. When Haim Ramon and Ehud Barak discuss the ‘we’re here, they’re there’ concept, they are trying to convince the public to accept the Oslo Accords even without the nice vision of a new Middle East. Instead, they simply advance separation with the promise that we Israelis won’t have to see Arabs anymore. But the forced, binary separation between Israel and a state of Palestine in the West Bank and Gaza is a technical, rather than architectural solution and is entirely artificial.

Another good example of an ‘architectural’ – rather than technical – security solution happened immediately after 1948. Following the armistice agreements between Israel and Jordan, the old railway track to Jerusalem (which is on the Israeli side of the ‘Green Line’) touches the Palestinian village Battir on the Jordanian side which raised a security challenge. A purely technical approach – the sort of thing Israel would do now – would have entailed building a huge fence. Instead Moshe Dayan came to an understanding with the villagers under which they received permission for direct access to tend to their farmland (which was located on the Israel side of the Green Line) in return for ensuring security for part of the train line. Such human complex systems are all about creating balance. Total solutions only appear in mechanical systems.

I count myself amongst those who believe that Israelis have no chance other than to live together with Arabs. I also believe that a hybrid phenomenon of what I call ‘emerging equilibrium’ is developing between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea which reflects a new order and which offers a lot of hope. One interesting example of this appears in Nazareth in northern Israel where two national entities share the same geographical space but are arranged in a way in which each one finds places which reflect their own state or people. Jews and Arabs in Nazareth coexist and work together but their way of life – their shops and food etc. – are organised differently. If we allow greater numbers of Palestinians to enter Israel to work, and try to facilitate daily interactions which create life-connections between people, this type of model can ultimately emerge within the entire Land of Israel.

I think you are missing one major component of your argument. That Judea Jerusalem and Samaria are the Jewish heart of the country, they are the Core while Tel Aviv is the the periphery of Zionist Jewish aspirations. The presence of the Muslims at the Core National Territory is the unlawful occupation of a foreign belligerent invader. It is the right and obligation of Jews to live in the core of their country, not some military necessity or strategy. The presence of Muslims should be tolerated as a long as they are peaceful, and cannot be tolerated if they are warring or preparing war. The whole focus must be shifted from Security consideration to the Exclusive rights of the Jewish People to their land, negating all such cliamed rights of other peoples. If Muslims can lay a claim to the Land of Israel they should be able to lay a claim to anywhere else, Paris Rome, Andalus, and Detroit, that is what must be explained to our Western allies.

Gen. HaCohen’s recommendation is compelling for its combination of complex human interactions and an uncompromising strategic analysis. I would be interested to know his position regarding the civil status of the Arabs of the West Bank. He uses the example of Nazareth, whose residents are citizens of Israel. Is that his recommendation for the West Bank as well? What would be the process of dismantling and disarming the Palestinian Authority, while simultaneously encouraging the cultivation of personal, social, cultural, and commercial contacts between Jews and Arabs? And what would become of Gaza in this scenario? Would it remain as independent Hamastan permanently behind the wall that is currently nearing completion?

I appreciate that these questions go considerably beyond the general’s broad overview, but I would be most interested in hearing his thoughts on these points, however preliminary.

Thank you,

Peter Margolis