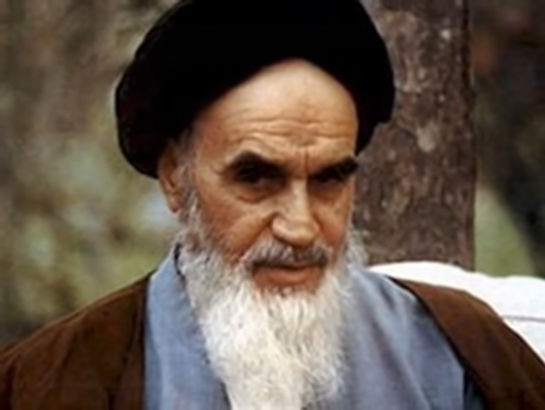

Adam J. Sacks chronicles the history of left and left-adjacent attraction to Islamist ideology. From early Soviet accommodation with political Islam – in sharp distinction to its attitude to Christianity and Judaism – to Foucault’s embrace of the Khomeini revolution in Iran, Sacks probes the irony of these accords coming from leftists, ‘whose antipathy to religion is presumably a part of their intellectual tradition.’

John Maynard Keynes famously dismissed the work of Marx, and in particular Das Kapital, by comparing it to the Koran: both being works of historical significance but without contemporary relevance. The pairing was astute, as much as the judgment was off, as moments of alliance between the two traditions, Communism and Islam, have proven explosive. Many may not remember that the revolution in Iran which deposed the Shah and led to the rule of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was once celebrated by many putatively on the left, whose antipathy to religion is presumably a part of their intellectual tradition.

This initial reception of Iran’s world-changing 1978-9 revolution was strange, and deserves another look, especially in light of current events. After all, this was the first openly Islamist government take-over in modern times, with a ‘divinely guided’ Supreme Leader at its head. So the embrace of this revolution – one ultimately, indissolubly linked with Islam – calls out for historical explanation for adherents of a philosophy one of whose most enduring ‘meme’ is that ‘religion is the opiate of the masses.’ Whatever one’s opinion on the regime of the Shah, the long-term effect of this revolution has been fateful. To wit, Hezbollah and Hamas trace their roots back to this original example. In 1982, just three years after Iran, the Muslim Brotherhood staged a revolt in Syria, and many also link the Iranian revolution to the assassination of Egypt’s peacemaking president Anwar Sadat in 1981.

The early western leftist responses urge a revisit, given the ongoing struggle to grapple with the reception of Islamic fundamentalism by progressives throughout the ‘western’ world. In chronological order, the cases to be discussed here begin with early Soviet stances on Islam, before moving on to western Trotskyists groups, and then to towering intellectuals like Jan Myrdal in Sweden and Michel Foucault in France. To many, Iran, after regime change from the Shah to the Ayatollah, was seen as an inheritor of the mantle of the dream of revolution. Whether or not it derived from a psychological wish fulfilment to see something – anything – other than monarchy or industrial capital in power, it bears the effort to scrutinise this revolutionary romance on its own terms.

This was by no means the first instance in which Marxist theorists and revolutionary activists had grown weary of the working class as the sole driver of the engine of world history. A line from a late Brecht poem carries some relevance here: ‘Would it not be easier… for the government to dissolve the people and elect another?’ Before 1978-9, Marxists had begun to ‘elect’ a new working class. Throughout the 1960s of the ‘New Left,’ thinkers like the German Jewish refugee Herbert Marcuse held that the working class as revolutionary was spent, and turned to students, minorities, even the unemployable and what Marcuse called the ‘substratum of the outcasts and outsiders.’ It was these groups that were possessed of a new revolutionary elan.

Islam and Early Soviet Rule

What some have called the ‘unholy alliance’ between Political Islam and Communism had deep roots in the early years of Soviet rule. While there is no direct causal link between early Soviet reception of Islam and that of the Iranian revolution, this offers essential background information. In short, Islam was never attacked outright in the manner applied to both Christianity and Judaism. Lenin and the early Bolsheviks cultivated strong ties with pan-Islamic activists throughout the Russian Empire’s Caucausian and Central Asian belt of Muslim polities, in such locales as Kazakhstan, Dagestan and Tajikistan. The legendary 1920 Congress of Peoples of the East, held in Baku, Azerbaijan, was largely an attempt to appeal to these peoples to join the Soviet cause. (The chairman and keynote speaker was Grigory Zinoviev, born Gershon Aronovich Radomysisky in Yelisavetgrad, today’s Kropyvynytski in south-central Ukraine.) Delegates from over 50 nationalities, from America to Afghanistan, and Kazakhstan to Korea, were present. Crucially, the nation with the second highest representation was Iran. (Controversial was the reading of a statement by Pan-Turanist ultra-nationalist Enver Pasha, who as member of Turkey’s war-time ‘Young Turk’ triumvirate had help to initiate the Armenian Genocide.)[1]

The Congress was part of an eastern pivot in the wake of the defeat in the 1920 war with Poland and the demise of short-lived Bolshevik regimes in Bavaria, Hungary and Berlin, all in the year 1919. Signalling that the 1917 revolution wouldn’t be spreading westward anytime soon, the officially termed ‘Soviet Eastern Policy,’ had as its central pillar toleration for Islam in many forms, without parallel with respect to the other Abrahamic faiths. As a result, early Bolshevik rule in the Soviet Union treated Islam in a manner entirely disparate, an exception to the putatively anti-religious stance of the Marxist movement. There was no widespread desecration of houses of worship in Muslim Central Asia, while churches and synagogues had become housing, clubs and even swimming pools. Nor was there any prohibition on practicing Muslim members in the party, while Orthodox religious convictions (of the Jewish or the Christian kind) could lead to party expulsion. In fact, separate Sharia law courts were still permitted to function alongside Soviet courts so that a parallel infrastructure existed for Muslim religious life. Friday became an official day of rest (unimaginable with respect to Shabbat) and state-supported Muslim religious schools or madrassas reached into the thousands. Bolsheviks followed the lead of local theorists of Muslim national communism such as the Crimean Tatars Mir Said Sultan-Galiev and Mullah Nur Vahitov, in the belief that ‘anti-religious propaganda’ should only be reserved for those Muslim nations deemed ‘most advanced.’[2] Even in the realm of theory, agitation against Islam cum religion was postponed to an undefined date in the future. One might venture that implicit in the Soviet stance was that Islam possessed still such vitality that it could not so easily be uprooted like the other related Abrahamic faiths.

Akin to affirmative action policies, these Soviet positions in Muslim majority areas derived from a conflation of issues of national liberation with those of cultural/religious freedom. These were groups who were perceived as having been downtrodden under Russian Imperial rule. On both the theoretical and practical level, this theoretical muddle of the national question and the religious question is one that persists to the present day. The early Bolsheviks’ overriding focus on ‘Great Russian chauvinism,’ or what today we might call ‘decolonisation,’ veiled the complexities of a variety of regimes of oppressions, especially those based around social norms and based on strict gender confinement. Whether the need for the hard theoretical labour of disentangling these in the context of Islam was ever recognised or not, scant literature on the topic was ever produced by the Bolshevik hierarchy. Evidence for this deficit may be seen in the recollection that issues today considered of primary importance – such as the imposition of the veil – were accorded secondary status, at best, in early Soviet thought and practice. When a campaign to oppose the veil did emerge in the later 1920s, it was from the ground up, instigated by local women, and touched off a firestorm of violence.[3] This curious early Soviet accommodation of Islam would, in any event, be short-circuited by Stalin’s omni-repression of anything at all distinct in his construction of a totalitarian state. And most historians agree that from the 1920s to the 1960s, Political Islam remained relatively muted the world over.[4]

Trotskyism and the Islamic Revolution

By the time of the Iranian Revolution, those most in favour of continuing any sort of Marxist alliance with Political Islam were those most on the outs with the post-Stalinist Soviet state – namely the followers of exiled and assassinated former Red Army chief, Leon Trotsky. Considered as the true heir to Lenin who was never given a chance, Trotksy’s followers are admittedly a fringe of a fringe, who broke with the Soviet regime, deeming it a ‘degenerated worker’s state,’ dominated by a bureaucratic caste that suppressed the working class. Trotsky, born Lev Davidovich Bronstein, into a Russian-speaking Jewish farming family in the Kherson gubernia (in today’s Ukraine), was exiled to Kazakhstan in 1928 and then deported from the Soviet Union one year later. In 1940, he was assassinated in Mexico City by an Argentine agent of Stalin’s who hid behind Belgian and then Canadian false identities, and who had taken up a love affair with a close confidant of Trotsky’s from Brooklyn. On 20 August 1940, inside Trotsky’s study, the agent struck him from behind with an ice axe; a struggle ensued, but Trotsky died the next day from his injuries at the age of 60.

Trotsky’s principal dogma of ‘permanent revolution’ did provide some theoretical basis or general inspiration for the latter-day openness to political Islam. This was a break with Stalin’s insistence on ‘socialism in one country,’ (later copied by Mao in China): industrialisation and the creation of a strong state were the alternate priorities at work here. In 1938, Trotsky did found a Fourth International, as a breakaway from the Soviet Comintern, later splitting into at least seven distinct factions. Such sectarian division became notorious: a well-known joke relates the refusal of one comrade to save another because he belonged to the wrong wing of that year’s faction of yet another socialist resurgence committee. Yet by the 1970s, the British Trotskyites of the Workers Revolutionary Party were experiencing a heyday. They had more members than the Communist Party of Great Britain and put out the first colour daily paper in British history. They attracted an orbit of adjacent celebrities and intellectuals from Vanessa Redgrave (who actually ran as a candidate on their behalf on three separate occasions) to Tariq Ali, CLR James and Isaac Deutscher. These may have been attracted by a more hard-nosed militancy absent in the more hippyish ‘New Left.’ Their leader was a tough Irish brawler, Gerry Healey, since the subject of numerous accusations of abuse and violence.

The party was taken with the conviction that Islam could be a critical factor in social ‘upheaval.’[5] Here we find that transference of the hope previously put upon the working class toward this something new, Political Islam, as a leading front for a new uprising of the downtrodden. These British Trotskyites not only defended the Iranian revolution and generally credited Ayatollah Khomeini’s leadership with the decisive role therein (a matter hotly disputed).[6] They also held, specifically, that it was the Iranian bourgeoisie (bazar merchants, the clergy and the educated) who were revolutionary and not the longstanding Iranian Tudeh Communist party. This instance and application of at least the ethos of ‘permanent revolution’ was naturally held to be quite heretical by other factions. In 1986, in fact, the ‘International Committee of the Fourth International’ expelled Healy and his British Workers Revolutionary Party over their stance on Iran. Yet even today, the official position of the International Communist League, a Trotskyist tendency, is to ‘defend Iran’ and ‘stand with Iran and Palestine.’[7]

This positioning remains doubly strange as the Ayatollah squashed, rather early, any hint of an affinity between Islam and communism, fulminating, for instance, against the Soviet incursion into Afghanistan in 1979. He declared ‘Islamic Marxism’ as a fiction and stated: ‘there has never been an alliance between Muslims, who are campaigning against the Shah, and Marxist elements.’ Khomeini denounced the fact that ‘some people have mixed Islamic ideas with Marxist ideas and the creation of a concoction which is in no way in accordance with the progressive teachings of Islam.’ And by 1980, just a year into the Revolution, Tudeh (Iran’s Communist Party) party headquarters had been sacked, and by 1983 they were closed for good, with dozens of party activists executed in the aftermath. Despite all this, the Workers Revolutionary Party remained a fervent supporter, declaring such support ‘unconditional. ’ This endorsement went up to and including the aforementioned suppression of left-wing groups and the imperialist war of the regime against Iraq in 1982.

Intellectuals Defend the Iranian Revolution: Myrdal and Foucault

Corners of support were found not just in fringe leftist parties but even amongst star intellectuals. The Swedish Sartre, Jan Myrdal, the son of Nobel Prize winners and scion of the elite, was a die-hard anti-imperialist convinced that Islam was somehow a proletarian religion in a category apart from Christianity, etc. As late as the 1990s, this most visible and published intellectual of 20th century Sweden defended not just Khomeini’s Iran but also Saudi Arabia. Myrdal went one step further when, on a trip to Iran in the 1990s, he defended the Ayatollah’s fatwa against Salman Rushdie in 1989, suggesting that it furthered the ‘oppressed Muslim masses in their struggle for human dignity.’ As recently as August 2022, Rushdie was stabbed multiple times by a young assailant before a public lecture in New York. Iran state media celebrated the attack.[8]

This sort of ‘left covering’ or ‘fairy-tale leftism,’ brushes to the side many other factors at play in the dynamics of the leadership of the Islamic Republic.

Often overlooked is the strong streak of Shia-inspired martyrdom at work in Iran’s Political Islam. After all, Khomeini was wont to repeat, ad-nauseum, ‘we are men of war, looking forward to martyrdom, ‘which resembles more what Marx termed Napoleon’s permanent war than Trotsky’s permanent revolution. Also, the specific conception of leadership at work in Iran is hard to disentangle from distinctly Shia conceptions that hold that leaders enjoy divine guidance and are free from error, beliefs that approximate the modern Catholic dogma of ‘papal infallibility. ’

Perhaps the most well-known and debated case of revolutionary romance with Iran was that of the French star thinker Michel Foucault, whose theories remain absolutely de rigeur in the academy the world over. Every methods seminar on the humanities has to this day at least a week devoted to Foucault He pioneered a Nietzsche-inspired ‘geneaological’ method to the humanities, and an analysis of power as such, which he applied to great effect in various fields such as sexuality, the prison system and mental illness. A complex and contrarian thinker, Foucault possessed grave doubts over the narratives and principles of European modernity and western modernisation. He rejected all forms of developmental discourse and in this sense, Foucault marks a breaking point with the Marxist tradition. Paradoxically he was criticised, in the context of the Iranian revolution, by leading Marxist thinkers like Maxime Rodinson as being possessed of ‘excessive hope,’ and that ‘gaps in his knowledge of Islamic history’ enabled him to miss that even at the very early stages the revolution ‘operated by no means in the humanist sense.’[9]

Nevertheless Foucault is still vaguely conceived as a ‘leftist’ thinker, despite the fact that the starting point and methods of Foucault are entirely apart from those of dialectical or historical materialism. A sceptic of the Enlightenment, for instance, Foucault saw the industrialisation and modernisation attempts of the previous regime of the Shah (understood as an instance of a top-down ‘white revolution) as themselves archaic and superannuated. In this he even echoed the words of Khomeini who claimed in an interview with Le Monde that ‘it is the Shah who is opposed to civilization and who is living in the past…’[10] He was entirely taken with the transformative power of the politics of the Iranian revolution. Entranced by the sense of novelty, it was as if he was desperate for new ideas, stemming from the persuasion that those in the west were somehow exhausted. Visiting Iran twice at the peak of the revolution (in September and November of 1978) he claimed to see the literal embodiment of the old Rousseauean idea of the ‘collective will,’ and used romantic imagery such as: ‘there was literally a light that lit up in all of them and which bathed them all at the same time.’[11] He coined the term ‘political spirituality’ to denote an enchantment of history and employed it as an alternative to a more Marxian notion of historical determinism. Yet when it came to scrutinising the role of religion, Foucault often resorted (perhaps wilfully) to obtuse circumlocutions: ‘religion constituted a force that perpetuated the hermeneutics of the subject on the streets of revolutionary Iran.’[12] Foucault went on to personally interview Khomeini and proclaimed this Islamic movement as stronger than anything Marxist or Maoist. It is here that one may find the intellectual roots of Judith Butler’s, a Foucauldian thinker, more recent pronouncement that Hamas and Hezbollah are social movements that are progressive and that are part of the global Left.

Even more conventionally Marxist leaders such as Fidel Castro would gradually begin to praise ‘Koranic-style’ governance. Fidel had begun his long reign in Cuba with the expulsion of foreign priests and multiple Catholic orders, and had nationalised all Catholic schools. In 2007, while meeting with Iranian Health Minister Mohammad Farhadi, he praised the vision of Khomeini and said the Koranic model of government should be considered as a substitute for western-style systems.

The Global Left’s ‘protectionist’ stance on Political Islam

As one leading Iranian feminist once said, ‘the left shouldn’t be seduced by a cure worse than the disease’.[13] Even Marx himself was convinced and had well established that some social systems could well be worse than capitalism. This Islamic Republic, once vaunted by some of the leading intellectuals of the west, has conducted up to 100,000 executions of political prisoners, systematic repression of Bahai adherents including expulsion of members and destruction of cemeteries and holy sites, as well as the ongoing demonisation and repression of Kurdish people who are discriminated against in housing, employment and education. Above all, the human and social rights of women have been entirely erased in a regime that regularly practices flogging, and recently intensified its longstanding forced imposition of the veil. Whenever a definitive story of the erosion – even collapse – of the Global Left in the era of neoliberalism and globalisation comes to be written, one could do worse than to highlight this ‘protectionist’ stance on Political Islam. A blind spot in theory and practice, these attempts at coalition building have at the very least relinquished a certain moral high ground accorded Marxists by a steadfast faith in materialism, and science. At worst, it has provided cover for unpredictable and uncontrollable occult factors in world politics which have repeatedly shocked and devastated the world. One might call it a warning from history, about the chaotic, erratic and ultimately dangerous prospects of any regime that believes itself touched by ‘divine guidance.’

[1] See John Riddell. To See the Dawn: Baku, 1920-First Congress of the Peoples of the East. (1993). United Kingdom: Pathfinder.

[2] See Ben Fowkes & Bülent Gökay (2009) Unholy Alliance: Muslims and Communists – An Introduction, Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, 25:1, 1-31, DOI: 10.1080/13523270802655597

[3] Keller, S. (2001). To Moscow, Not Mecca: The Soviet Campaign Against Islam in Central Asia, 1917-1941. United Kingdom: Praeger.

[4] See Fokes and Gökay.

[5] See Bruckner, P. (2012). The Tyranny of Guilt: An Essay on Western Masochism. United Kingdom: Princeton University Press.

[6] https://www.wsws.org/en/special/library/fi-14-2/09.html

[7] Ibid.

[8] For more information, see here https://janperry7.wordpress.com/jan-myrdal-fralsaren/

[9] See Ghamari-Tabrizi, B. (2016). Foucault in Iran: Islamic Revolution After the Enlightenment. United States: University of Minnesota Press.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Afary, J., Anderson, K. B. (2010). Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism. Germany: University of Chicago Press.