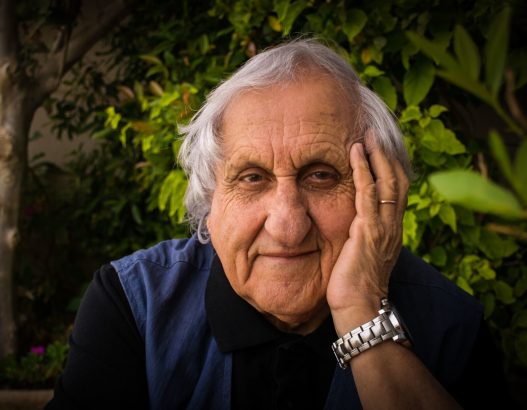

Ranen Omer-Sherman, JHFE Endowed Chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Louisville, surveys the life and work of the great A.B. Yehoshua, a giant of Israeli literature and national life. Taking a wide view of the Yehoshua canon, Omer-Sherman asks us to see how ‘interrelated his works are in their steadfast concern with the paradigm of Responsibility… From both the individual and the collective,’ Omer-Sherman argues, ‘Yehoshua demanded a fuller recognition of the responsibilities inherent in Jewish identity across time and space, most acutely in the Jewish homeland.

It is hard to believe that it has already been almost three years since the death of A.B. Yehoshua (1936-2022), a giant of Israeli literature who was still publishing essays and novels up to the time of his death. With the passing of so many canonical Israeli writers in recent years, including Amos Oz, Nava Semel, Aharon Appelfeld, and Meir Shalev, coupled with Israel’s global unpopularity amidst the Gaza war, foreign interest in Hebrew writing may be diminishing. Yet now more than ever, Yehoshua’s morally imaginative voice, stressing reason, reconciliation and above all the imperative of responsibility seems worth our urgent attention. In a biography completed shortly after Yehoshua’s passing, Avi Gil offers an amusing anecdote revealing that in childhood Yehoshua already demanded a right to participate in the tempestuous ideological debates besetting Israelis after the establishment of the state. In a contract he solemnly handed to his parents in 1949, the thirteen year-old future writer claimed the right to ‘talk back to those who according to my logic are mere fools and to irritate as much as possible because in my opinion I am good at it.’ This insistence on questioning the moral entanglement of the individual and the Jewish state served as the palimpsest for what was to follow.

When contemplating Yehoshua’s vast literary corpus of eleven novels and numerous novellas, short stories, plays, and polemics, it is easy to become so absorbed by his oeuvre’s exuberant sprawl of spatial and temporal settings, the myriad desires and conflicts of his singular characters, that one might overlook the underlying force that energises it all. The writing is so imaginative that one may not recognise how interrelated his works are in their steadfast concern with the paradigm of Responsibility, whether emanating from the self and the collective, from Yehoshua as a public figure, or from each of his characters grappling with their diverse challenges. This abiding concern is the foremost impetus of his creative and polemical works, the force that sparks his moral and aesthetic imagination, whether exploring gaps between the secular and religious, East and West, Diaspora and Israel, Jewish Israelis and Israel’s Palestinian minority. From both the individual and the collective Yehoshua demanded a fuller recognition of the responsibilities inherent in Jewish identity across time and space, most acutely in the Jewish homeland. In the wake of the 7 October massacres and the brutal Gaza war, I find myself mourning the loss of his voice, the cri de coeur of outrage he would surely have directed toward Netanyahu and others bearing responsibility both for Israel’s staggering security failures and ongoing human rights violations. Yehoshua would surely have denounced Hamas but he would also have been in the forefront of those demanding that the government at last accede to the enormity of the responsibility it brazenly refuses to bear. Today, when so many Israelis feel dejected by a far gloomier reality than most anticipated, Yehoshua’s positive sense of responsibility is sorely missed. When asked what his father might have said in the aftermath of 7 October, his son Giddi responded, ‘I don’t know…but he would not paint a catastrophe. He would have come up with something original and positive. He would startle us with an unconventional idea to give us strength.’

Critic John Bayley once observed that ‘Yehoshua’s characters are born with an exasperating awareness of the wish for independence and the impossibility of being independent.’ The severity of that burden remained the paramount trial governing his work, which often took the form of what he called ‘the great debate between Israel and the Golah,’ a concern that spills forth in myriad instances, both allegorical and literal. One recalls the exasperated exhortations of Yehuda Kaminka, the retired Israeli teacher caught between America and Israel, in Yehoshua’s second novel A Late Divorce: ‘Homeland will you ever be a homeland?’ Tragically, in the wake of excruciating suffering, this remains the empirical question still festering for many Israelis. And yet Yehoshua would almost surely have answered in the affirmative.

Avraham Gavriel Yehoshua was born in Jerusalem to Malka (nee Rosilio) and Yaakov Yehoshua. An erudite folklorist and expert on relations between Jewish and Arab in Mandatory Palestine, his father belonged to the community of Jews who had lived in Jerusalem for generations; a grandfather was the chief justice of the city’s Sephardic religious court. Yehoshua’s Moroccan-born mother moved to Jerusalem just four years before his birth. After the 1948 War of Independence and the siege of Jerusalem, during which shrapnel from a bomb on Ben Yehuda Street destroyed part of their house, Yehoshua’s family moved to Talbieh, a prosperous neighbuorhood where he attended Jerusalem’s Gymnasium, established in 1909 as the city’s first modern high school. He was nicknamed ‘Bulli’ by his classmates, and that affectionate moniker stuck to the end of his life. Yehoshua studied Hebrew literature and philosophy at the Hebrew University and later taught Hebrew and comparative literature at Haifa University.

Bulli and Rivka (nee Kirsninski) married in 1960 and the latter became a highly respected psychoanalyst and clinical psychologist at Haifa’s Carmel Hospital. In later years Rivka was always the first reader of the drafts of his manuscripts and it is hard to imagine that the deeply psychoanalytic nature of his works did not owe in part to their conversations. Given the pervasive presence of dysfunctional households, adultery, broken marriages, and sexual misconduct in many of his works, it is almost amusing to note the utterly traditional nature of Yehoshua’s marriage as well as its remarkable endurance from 1960 until her death in 2016. From 1963-1967 he lived and taught in Paris while Rivka worked on her doctorate in clinical psychology, a creatively fecund period that served as a source of inspiration for one of his most infamously troubled characters, Gabriel, the irresolute philanderer and yored [A culturally pejorative term denoting one who descends or emigrates from Israel] whose untethered identity in France and weak character is intrinsic to the dysfunctional drama that plays out in The Lover, Yehoshua’s most explicitly allegorical novel.

Despite The Lover’s themes of betrayal and grim post-1973 War atmosphere, optimism stealthily emerges from its portrayal of the rejuvenating potential of Haifa itself, where even during Israel’s most tense days (including the trauma of 7 October), good relations between Jews and Palestinian Israelis usually persevere in a blue collar city that takes pride in its largely secular, pluralistic identity. Little wonder that Yehoshua’s most Haifaian work concludes with the word ‘hope’ (also the title of Israel’s national anthem). When toward the end of his life Yehoshua reluctantly departed from his beloved city, the mayor of Haifa saw fit to name an entire square for The Lover, perhaps for the novel’s quietly redemptive affirmation that the city might serve as a paragon for the country’s future. As Yehoshua told Nili Scharf Gold, ‘Haifa is the model for what I wanted Israel to be. It was the city where I lived and where I created and which I loved… I also saw harmony between Jews and Arabs, and a social consciousness. Haifa is Israel at its best’ (227).

Until his death, Yehoshua enjoyed an unassailable stature as a founding father of what came to be known as the Hebrew New Wave, writers who came of age after the establishment of the state and were savvy interpreters of the dramas of contemporary Israeli life. Yet readers who have never read him should not be misled into thinking that because he engages with the heaviest matters of Jewish and Israeli destiny and world history, Yehoshua’s writing is grim in tone or outlook. Indeed, few novelists of his generation handled their lofty themes with quite the sparkling wit and lightness of touch Yehoshua mustered, nor with such stunning psychological insight and empathy. In achieving those ends, he created a lineage of beleaguered male anti-heroes such as Adam in The Lover or Yirmiyahu (Hebrew for Jeremiah) the bereaved father in Friendly Fire. The latter is so embittered by the senseless death of his soldier son in the occupied West Bank that he altogether repudiates the awful ‘blessing’ of citizenship in the Jewish state, wrathfully gloating:

I freed myself of the leash of the forefathers. I look on from afar, indifferent and liberated, safe and sound in a place where there is not a shred of prophecy, or of fury, or of consolation. And here, even if they dig up the entire ground, they won’t find a trace of a dry Jewish bone… no floor tiles from a destroyed synagogue… no testimonies about pogroms and the Holocaust. There’s no exile here, no Diaspora… They don’t fuss about assimilation or extinction, self-hatred or pride, uniqueness or chosenness. The people around me are free and clear of that whole exhausting and confusing tangle.

Though Yehoshua’s own views were of course antithetical, it is to his credit that he conveys captures the life-destroying grief and despair of a character who serves as surrogate for countless grieving Israeli parents whose children have paid the ultimate sacrifice.

Along with his close friends Amos Oz and David Grossman, Yehoshua weighed in on burning political issues of his day. He emphatically embraced the mantle of critical citizenship, a role that seems less attractive to his immediate literary successors. Over the years, Yehoshua achieved notoriety for espousing a hierarchised set of oppositions that often outraged Jewish audiences in the Diaspora, scolding the latter for their continued failure to participate in the consolidation of Zionist hegemony and abandon the historical condition that culminated in Auschwitz. He famously rejected the American model of hyper-individualised identity (and the resultant violence of American society) preferring the sensibility of modern European democracies whose identities were based on a tight nexus of language, religion, and nationhood. He was embittered by what he considered the irresponsibility of the ultra-Orthodox, angry that they prioritised a life devoted to the study of sacred texts over contributing to the civic life of the nation (a sentiment expressed as early as The Lover) including the burden of army service.

Given his perverse inclination for provocative statements, Yehoshua could sometimes manage to provoke both the Israeli right and the left, such as with his avowed support of the First Intifada. Bernard Horn credits Yehoshua with a ‘casual audacity’ for his candour in taking up such positions. Like poet Yehuda Amichai, Yehoshua was uneasy about the post-1967 hyper-nationalist ecstasy over Jerusalem and its festering role in the conflict, telling Horn that:

I have had a strong ideological opposition to Jerusalem ever since 1967, especially in the late 1970s and 1980s when the American Jews were coming and playing with the Old City, as if it all were a kind of sacred toy. Afterwards, the intifada started and Jerusalem was again cut into two parts by the Arabs who were saying, ‘We are here also. Please. We are not a nonexisting entity. We are here. We are a living people. You cannot just impose upon us and take our houses, and push us here and there, you have to consider us. We are people, we have been living here for hundreds of years, so you have to take us into account.’ (Facing, 28-29)

If, in the eyes of some, Zionism’s ‘original sin’ was its uneven attention to the native Arab population, Yehoshua’s steady gaze always included the manifest presence of the Other. In the early post-1967 War days, Yehoshua was one of the few who believed that Jerusalem should be the capital of two states for two peoples. A similar logic led him to repudiate the fatal entanglement of Israel in the occupied territories, which of course was exacerbated by Arab rejectionism, which he saw as an expression of irrational religious impulses rather than a healthy, pragmatic national self-interest.

Critical milestones in his career moved Palestinian Arabs front and centre in empathic ways that inspired later generations of writers. Every decade or so, Yehoshua challenged himself by creating ever more complex portraits of Palestinian Israeli lives, from the mute figure who is the catalyst for the firewatcher’s moral discoveries in ‘Facing the Forests’ (1963), to the yearning adolescent in The Lover (Ha-Me’ahev, 1977), to the North African Muslim Abu Lutfi of A Journey to the End of the Millennium (Masa El Tom Ha-Elef, 1997), to the politically and ideologically varied cast of adult Israeli Palestinians and West Bank Palestinians in The Liberated Bride (Ha-Kala Ha-Meshachreret, 2001). Yehoshua never wavered in creating characters and situations where readers recognise the traumatic memories and joint claim to the land of both Israelis and Palestinians. The Liberated Bride was written in the midst of the Second Intifada, when the Oslo process had collapsed. This labyrinthine work manifests a deeply conflicted and even contradictory view of the fluidity of identity and borders between Ramallah, Jerusalem, and Haifa. More than any other novel of its era, The Liberated Bride presents readers with sharply realistic portraits of the dissimilar status that sharply divides Palestinian citizens of Israel and the stateless Palestinians of the occupied territories, the severe consequences resulting from legal prohibitions preventing Palestinians from the territories from residing in Israel, not shying away from the menace of terrorism. Yehoshua’s awareness of the impossibility of reconciling the incompatibilities of Zionist ideals with the tragic outcomes of decades of occupation makes this novel an especially vigorous work of moral questioning.

Two unexpectedly related works stand out for their unsettling explorations of the true nature of just what constitutes a civilised society. Yehoshua seems to have surprised himself by what was revealed to him during the writing process in his 2004 novel A Woman in Jerusalem [Shlichuto Shel Ha-Memuneh Al Mashabei Enosh], a deceptively lean work that novelist Claire Messud called ‘resonantly dense… at once Kafka- and Faulkner-esque.’ Yehoshua was explicit about the nature of the moral journey he unexpectedly experienced writing this spare, hallucinatory narrative:

I am not religious. But a certain religious energy erupted in this book. I tried to restore meanings that we have lost. The meaning of Jerusalem. The spiritual meaning of Jerusalem. Suddenly I noticed that Jerusalem has become rather tattered within the Jewish-Arab conflict… both we and the Palestinians are completely losing its global spiritual dimension.

Similar themes of social responsibility and spiritual awakening emerge in a very late work, The Tunnel, a lean novel in which the plight of Palestinian refugees is predominant, and includes an admiring portrayal of the activities of Road to Recovery, a volunteer organisation assisting Palestinians seeking medical care in Israel, some of whose staff were brutally murdered by Hamas, including the 83-year-old Oded Lifshitz whose body was returned to Israel in late February. The story concerns a retired Jewish highway engineer with advanced dementia who gets tangled up in the plight of a Palestinian paterfamilias living clandestinely in the Nabatean ruins of a Negev hilltop and that basically sums up its plot. The Tunnel may be relatively uneventful, yet it boldly lays bare the struggle over Israel’s national values. In both these novels, the plight of minorities stirs something in the protagonists, a dynamic Yehoshua himself once referred to as ‘a personal quest, a turbulence, an unrest,’ ultimately directed toward ‘accomplishing something, repairing reality and taking responsibility.’ As his last major work, The Tunnel reads as a bold expression of Yehoshua’s sanguine confidence that humanity and reason will ultimately prevail.

Many years ago, Robert Alter offered a surprisingly prescient observation about what distinguished Yehoshua’s literary imagination, a formulation that seems to have stood the test of time now that we have the benefit of reflecting on the entire oeuvre: ‘the characteristic Yehoshua world… is a world of incompletions. These incompletions manifest themselves both in projects undertaken and in acts of communication attempted.’ Yehoshua built his creations by wrestling with paradoxes, ambivalences, uncertainties and frustrations on various planes of signification – personal, sociopolitical, historical, allegorical – always enabling him to reflect anew on the challenging project of nation building and national identity, the incompleteness of which never ceased consuming him.

Yehoshua always demanded rigour and intellectual honesty in himself as he did others. Though he stubbornly clung to many of his convictions, he could prove startlingly adaptive, such as when his view of the Israel-Palestine conflict underwent a surprising reversal. Reluctantly disavowing the two state solution he had fiercely advocated since 1967, in the pages of Haaretz in 2018 Yehoshua urgently advocated a unified homeland for Jews and Arabs, with full equality for all:

the apartheid process striking deep roots in our life is far more dangerous, and uprooting it will soon be impossible… it is not the Jewish or Zionist identity that I fear for, but something more important: our humanity and the humanity of the Palestinians in our midst. We will live with the Palestinians for eternity, and every wound and bruise in relations between the two peoples will be engraved in the memory and passed on from one generation to the next.

It was a brave change of heart from his earlier anxiety about such comingling but as always it expresses his long and ultimately sanguine view of Jewish history and the incomplete Zionist enterprise: ‘Jewish identity existed for thousands of years as a small minority within large, powerful nations, so there is no reason for it not to exist also in an Israeli state even though it contains a Palestinian minority so large that it can be termed a binational state.’ Accommodating the other thus endured as the greatest catalyst for Yehoshua’s literary and moral imagination, tirelessly wrestling with the collective responsibility of his beloved homeland. Obviously in the bleak post-7 October reality, fewer Israelis and Palestinians than ever seem to have patience for working toward a two-state solution and it is impossible to predict how Yehoshua’s sensibility might have shifted. Yet even in our own traumatised moment, he would surely remind us that – no matter how much some might wish otherwise – neither Israelis nor Palestinians are going away.

—

I am grateful to Yael Halevi-Wise for her astute insights that strengthened this essay.