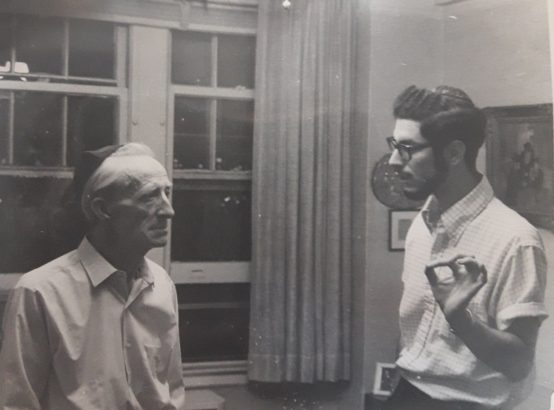

Yisrael Medad spent many hours with the poet and Revisionist Zionist Uri Tzvi Greenberg (1896-1981) at Greenberg’s Ramat Gan home in the decade prior to his death. ‘He prayed wrapped in tallit and tefillin, rushing back-and-forth from wall to wall in his living room’ he recalls, ‘less praying than conducting a demanding conversation with God’. Medad rereads Greenberg’s 1929 poem Sicarii II, with its demand for a rebel’s mindset and a revolutionary spirit, its hymn of praise to Jewish self-assertion and self-emancipation, as a resource for Jews today, inside and outside Israel, in the face of the existential Iranian threat and rising global anti-Semitism.

In Mandate Palestine it was not only the political writings and speeches of Ze’ev Jabotinsky and his fellow Revisionist movement leaders that propelled Zionism’s nationalist camp into a confrontation with both Mufti-instigated terror and the British authorities. The role of literature to the bestirring of resistance actions was also critically important.

And this was not unique. Ireland, Poland and other countries also showed that a genuine national feeling emerged from cultural identity as much as a historical narrative or a vision for a future. This is appreciated by sociologists as ‘a founding myth’ or an ‘invented tradition‘.

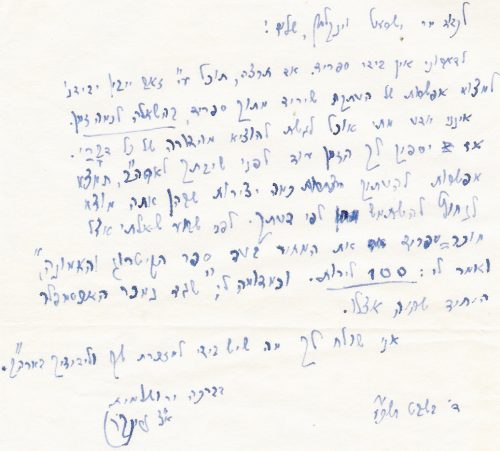

(Letter to Yisrael Medad from Uri Tzvi Greenberg, February 1967)

(Letter to Yisrael Medad from Uri Tzvi Greenberg, February 1967)

Coming from the camp of the socialist left and as one viewing himself as the ‘Singer of the Halutzim’, Greenberg, who began to publish his poetry in 1912 in both Yiddish and Hebrew, arrived in Mandate Palestine in December 1923. He also published polemical opinion columns in the Histadrut’s Davar newspaper and the Kuntres weekly, but found himself gravitating into the Jabotinsky camp between 1927 and 1929. Already in June 1927, the HaPoel HaTzair weekly was complaining that Davar, under Berl Katznelson’s editorship, was not paying sufficient attention to Greenberg’s ‘spiritual Revisionism’. The fact that Ze’ev Jabotinsky had returned to Eretz-Yisrael in October 1928 and, having taken over the Doar HaYom daily, began publishing Greenberg, perhaps encouraged Greenberg’s enlistment into the Revisionist wing of Zionism. His ideological shift became further apparent with the publication of his ‘Chazon Echad HaLigyonot’ (The Vision of One of the Legionists) in 1928. Greenberg, although lauding the pioneers of the soil, framed their activities in a near-militaristic perspective, comparable to Josef Pilsudki’s Polish Legions (Legiony Polskie). And like Pilsudski, it could be said of Greenberg that he had ‘taken the red streetcar as far as the stop called Independence and gotten off.’ On August 23, he personally witnessed in Jerusalem how the British confronted a mob of some 150 Arabs, shouting and waving daggers, swords and nabout sticks, and how Jews attempting to make their way from the Jaffa Gate to toward the city center were struck and beaten. Undoubtedly, this reminded him of his and his family’s own miraculous escape from slaughter by the Poles in Lviv in November 1918. The Zionist themes of ‘conquest of labor’ and ‘conquest of soil’ were not originally intended to symbolise any military connotation, but were transformed by Greenberg into preliminaries to a ‘conquest of the land’.

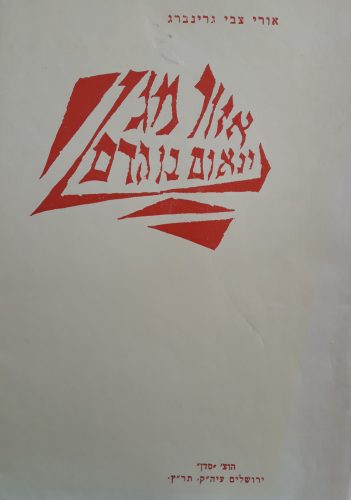

Greenberg’s poetry became more responsive to Arab hostility (and British obsequiousness to that hostility) to Zionism’s goals of reconstituting the Jewish National Home, a goal that had been guaranteed by the League of Nations in 1922. His next three volumes, ‘Kelev Bayi’ (House Dog), 1929, ‘Aizor HaMagen v’N’um Ben-HaDam‘ (The Zone of Defense and the Son-of-Blood’s Speech) 1929 and ‘Sefer HaKitrug v’He’Emunah‘ (Book of Accusation and Faith), 1937, gave a poetic expression to the spirit of the future underground resistance groups, the Irgun and the Lechi.

(Front cover of Aizor HaMagen v’N’um Ben-HaDam)

As an example, I have selected the fourth poem in Greenberg’s volume, ‘Aizor HaMagen v’N’um Ben-HaDam’, published in mid-October, just two months after the horrific 1929 riots. It is taken from The Collected Works of Uri Tzvi Greenberg, Volume 2., and the translation is my own.

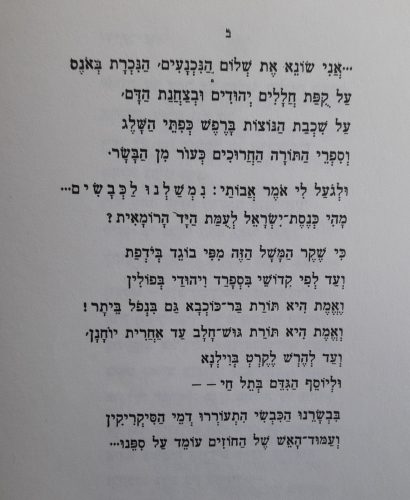

(Sicarii II as it appeared in 1929)

Sicarii II

…I despise the peace of those that surrender, forcibly concluded

Over the collection of Jewish dead and the stink of blood,

Over a layer of feathers in garbage as if they were snowflakes

And singed Torah scrolls as if of human flesh.

And I am disgusted by our forefathers’ saying: We are compared to sheep…

What is the Congregation of Israel as opposed to the Roman hand?

This analogy is false, coming from the Traitor of Yodfat

And up until the Martyrs of Spain and Poland’s Jews.

For the Law of Bar-Kochba is truth even as Betar fell!

And true is the Law of Gush-Chalav until Yochanan’s last,

Even unto Hirsch Lekert in Vilna

And to the one-armed Yosef at Tel Chai –

In our sheep’s flesh, the blood of Sicarii has awoken

And the Pillar of Fire of our seers

appears on our threshold…

In this poem Greenberg places an immediate emergency – the pogroms of August 1929 – in a familiar religious and historical frame of reference. Layers of history are invoked to mobilise and encourage and to suggest the value of reviving old patterns of response to contemporary threats. He is enlisting recruits for a new Hebrew renaissance, which will correct the past mistakes of the Jewish people through force, through violence, and return them to the ‘fighting nation’ of David, of Samson, of Bar Kochba.

Greenberg employs phrases or terms straight out of Talmudic and Rabbinical sources or prayers such as the sheep comparison found in the Tachanun version said on Mondays and Thursdays, taken from Psalm 44:23 – ‘for Thy sake are we killed all the day; we are compared to sheep for the slaughter’. The Pillar of Fire recalls the trek of the Children of Israel leaving Egypt. The Sicarii were the extremist faction during the siege of the Second Temple who used short swords, hence their name. The events of 2000 years are made available as resources for Jews in Palestine.

Greenberg’s choice of ‘heroic fighting Jews’ is eclectic yet subversively inclusive. Hirsch Lekert was an anti-Zionist Bundist who had attempted to assassinate the governor of Vilna, General Victor von Wahlin, in 1902 and was hanged from the gallows. His last words, in folk attribution, were ‘Vengeance must be taken!’ Trumpeldor, a rare Jewish officer in the Czarist army, who founded the HeChalutz group, served in the Zion Mule Corps, was a socialist and who fell defending Zionism’s most northern Galilean foothold, Tel Chai in March 1920. His name was used by Jabotinsky for his youth movement, Betar-Brit Yosef Trumpeldor. Bar-Kochba, Josephus and Yochanan were commanders of revolts and military battles against the Roman occupiers. He adds those who died in pogroms, Church Inquisition torture chambers and autos-de-fe. Yet Greenberg’s twist is the turn this lachrymose history around by returning to the Sicarii to create a new myth.

The Brit HaBiryonim revolutionaries of Abba Ahimeir had not yet been organised. The Biryonim had been yet another faction in the Great Revolt against Rome and they, according to Tractate Gittin 56a, where those who burnt the grain stores of the city. Their appellation had been resurrected by the poet Yaakov Cahan in his 1903 poem Biryonim whose refrain, ‘Through blood and fire did Judea fall / Through blood and fire will Judea arise’, was adopted, ironically, by the HaShomer defense unit in 1907. Their demonstrations against British policies came after 1930 as well as the 1933 stealing of the swastika-adorned flags flying over the German consulates in Jerusalem and Jaffa. Neither was the Irgun or the later Lechi groups operative yet. But here was Greenberg calling upon the potential activists to heed Jewish history, to adopt not the quietism of Exile but the heroic educational models he provided. It need be recalled that the Rabbi of Minsk, in his sermon on Lekert’s hanging, cried out ‘our people were always proud of one thing, that we never had rebels among us’ and here was Greenberg, demanding a rebel’s mindset, an agenda of revolutionary spirit, a reversal of a hankering after an other-worldly redemption in some imagined messianic era. For him, the messianic element was in the Jews’ blood but it needed to be brought to a boiling point.

In rereading Sicarii II, I am reminded of what the late Geula Cohen said at a Bar-Ilan University conference dedicated to Greenberg’s poetry held in May 2006, on the 25th anniversary of his death: ‘his poetry demands all the intellectual and psychological oxygen that one possesses’. Bialik once described Greenberg so: ‘But Greenberg possesses a discerning, observing eye and he sees what is on the walls and what is beyond them and because of that, he climbs those walls, and that is the secret of his poetry‘). Bialik Publishing House has so far published 15 volumes of Greenberg’s Hebrew poetry and opinion columns and even one of his drawings. More volumes are planned, including several of his Yiddish works, in translation.

Outside the Camp of the Halutzim

Greenberg was considered as ‘outside the camp’ by the Left (the reference being: ‘He shall remain unclean… He shall live alone; his dwelling shall be outside the camp’, Leviticus 13:46), first for abandoning Socialist Zionism, then for joining with Jabotinsky and Ahimeir and finally, for becoming a Member of Knesset for Herut in 1949. The de rigueur leftist epithet of ‘fascist’ was applied to him. Oddly enough, from the mid-1940s until the late 1950s, Haaretz published his poetry, mostly lyrical, and its Schocken Publishing House issued his majestic Holocaust volume, ‘Rechovot HaNahar‘ (Streets of the River), a title recalling Kabbalistic terminology, for which Greenberg was awarded the Bialik Prize and, in 1957, awarded an Israel Prize. Greenberg rejected the term Holocaust, preferring Churban Beit Yisrael b’Europa (the Destruction of the House of Israel in Europe), with churban recalling the destruction of the Temple. At the very same time, he was also contributing nationalist-themed poetry to the political-cultural monthly, Sullam (Ladder), published by Israel Eldad, the foremost right-wing intellectual. By the decade of the 1960s, it was becoming impossible to purchase any of his earlier books as he refused to permit their republication, explaining that he felt the generation was not worthy enough to appreciate his writing.

His lyrical output was described by Dan Meron as ‘an attempt on a heroic scale to reintegrate—through lyrical meditation and far-reaching explorations of a dozen different poetic themes—the fractured life and mind of a poet who had experienced a lifetime of chaotic and disruptive events… He had to put together and unify at least five different elements that did not necessarily dovetail: personal memory; an ideological insight into the essence of his mission as a political persona; a mystical, essentially kabbalistic, view of nature and of the process of life as its core; a new metaphysics of death and dying; and a new poetics that had to find a synthesis between the poet’s early burgeoning modernism and his later neotraditionalism.’

I spent many hours with Greenberg at his Ramat Gan home in the decade prior to his death. He prayed wrapped in tallit and tefillin, rushing back-and-forth from wall to wall in his living room, less praying than conducting a demanding conversation with God. Afterwards, we would review some of his poetry and his intended meaning. Or we would recall figures he had known, some of whom, like David Ben-Gurion, he would mimic. He would reminisce about his early childhood and his years in Poland in the 1930s, editing the Revisionist media, about being spat upon when he returned for the Arlosorov murder trial and about the two years he spent in the Knesset.

But to return to the poem Sicarii II and its rereading. What is remarkable is that it opens not with a description of the slaughter of those three weeks in August 1929 in Hebron, Safed, Be’er Tuviah, Har-Tuv, Kibbutz Hulda and other locations where Arabs slaughtered Jews, burnt fields and property and otherwise committed crimes of violence and destruction. Instead, he opens with a principled political position: a peace with those that perpetrated such foul actions is unacceptable to him.

Greenberg is setting forth, foremost, a political message: to come to an arrangement with the leadership of the Arabs of Mandate Palestine which is intended to fall back to a previous peaceful period is simply wrong. While he bemoans and mourns the loss of life and damage, Greenberg’s imagery evokes hundreds of years of Jewish history as a backdrop to what the reader can expect in the near future. He recalls the blood shed by martyrs, collective and singular, from all sections of the Jewish people, and then indicates, and points to, a conclusion: while Jewish blood has been spilled, it has, in another fashion, been awakened. He expresses disgust at the attitude of Jewish leaders which brought about this Jewish bloodletting. His revulsion of the scenes of slaughter, is also a revulsion at those Zionist leaders that permitted such events to happen. It is not only ‘our forefathers’ but our contemporary leaders that are at fault.

Greenberg is using his poetic genius to sharpen awareness of the need for a recalibration of the policies required to assure the success of the Zionist enterprise in the Land of Israel. This territory is not a ‘land of the Exile’, a corner of the Dispersion. It is the territory of recall of the heroic deeds of the Hebrew nation, of David the guerrilla warrior, his ‘mighty men’, of the Zealots, Bar Kochba and the Sicarri. It is the land of a reignship, of possession.

As our forefathers followed a Pillar of Fire, Greenberg set about to relight another Pillar. In mid-January 1937, he added to the blaze of revolt and sacrifice which his previous poems had ignited with the appearance of ‘Sefer HaKitrug v’He’Emunah’ (the Book of Accusation and Faith) with its 169 pages containing poems of the last six years, the last one finished the previous September. It contains some of his more immortal lines of nationalist poetry such as

Your Rabbis taught: A land with money is purchased

You buy the field and plunge a hoe into it.

And I say: A land is not bought with money

And with a mattock you also dig and bury the dead.

And I say: A land is conquered with blood…

…And the blood will determine who will rule here.

And

And I say: there is but one truth, not two,

Just as there is one sun and not two Jerusalems.

Greenberg, the progeny of Hassidic Rebbes, steeped in Biblical and Talmudic lore, Kabbalah and the poetry of Iberian Jewry, insisted his was not only a prophetic voice but one that with the full authority of Jewish history and destiny charged his readers with a holy task and ordered them to accomplish it.