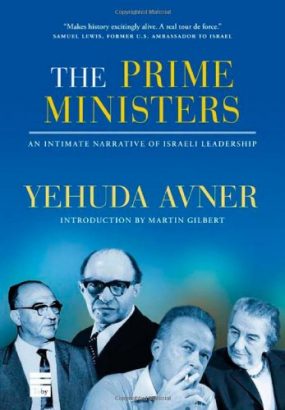

‘The ultimate insider’s account’ wrote George Gruen on the release of Yehuda Avner’s book The Prime Ministers in 2010. In his usual limpid prose, Fathom’s literary critic Liam Hoare gives us a compelling portrait of Avner, the man Menechem Begin once called his ‘Shakespeare’, and his journey from post-war Revisionist Zionist circles in Manchester, England to the Prime Minister’s Office in Jerusalem, Israel.

1.

Not long after the end of the Second World War, Lawrence Haffner’s mother escorted the boy — by then in his late teens — to a Revisionist Zionist meeting in Manchester. ‘A deep-buried fury burned within the Zionist circles of Manchester’ at that time, he recalled later in life — a period of blood and fire when a Jewish insurgency was conducting a violent underground campaign against British rule in Mandatory Palestine. Raised in a religious, Revisionist household, that night Haffner was first introduced to what he called ‘the Begin ideology’ — that signature blend of Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s 19th-century liberalism and nationalism with Menachem Begin’s eastern European religious mysticism. A love affair was born.

By the time of the bombing of the King David Hotel in July 1946, Haffner was already heading towards the door marked Exit. He was besotted with Begin as an underground revolutionary and man of action and had, by that time, ‘discovered a religious Zionist youth movement called Bnei Akiva,’ one which he credited with making him ‘impudent and bold’ in the face of antisemitic hostility in Manchester. Feeling its gravitational pull, on 3 November 1947, Haffner boarded a Greek vessel named The Aegean Star and headed for Palestine. ‘It was a time when visas to Palestine were so hard to come by that, in obtaining one, I decided in my own mind I would not come back.’ In Palestine, Haffner Hebraised his name to Yehuda Avner.

Avner, of course, went on to have a storied career as a prime ministerial advisor to and speechwriter for Levi Eshkol and Golda Meir, Yitzhak Rabin and Menachem Begin, an experience Avner documented in 2010’s The Prime Ministers — his testament of all that he saw during his decades in service of those who built the State of Israel. ‘I was the note-taker’ Avner explained in an interview with Tablet five years prior to his death in 2015, ‘employing my own invented shorthand which I would then transcribe for the official record. … I never threw away those scribbles. I confess I was naughty. Not that I ever contemplated I would one day use them.’ Use them, however, he did.

His career at the right hand of power was, to Avner at least, an unlikely one after his emigration to Palestine and time spent as a representative of Bnei Akiva. When he joined the Israeli foreign ministry in 1959, it — and the state — was being steered by the guiding hand of the Mapai which, in Avner’s eyes, ‘had but one idea of government — to preserve intact its absolute grip on the political power bequeathed to it by its historic dominance over the entire Zionist movement’. In the 1950s, ‘Mapai members filled the ranks of the civil service, the city halls, the local councils, the university senates, the officer corps, the industrial plants, and every other significant job on offer’.

Avner, on the other hand, was not only religious but also a member of Hapoel HaMizrachi, a small party oriented around the movement of religious kibbutzim. In 1956, Hapoel HaMizrachi merged into the National Religious Party. Whether these details were really hindrances or not, Avner’s ‘kibbutz credentials, command of English, and superficial familiarity with African affairs’ were enough for him to ‘pass muster with the appointments committee’ and win a job in the foreign ministry at a time when then-Foreign Minister Meir was looking to expand Israel’s reach in sub-Saharan Africa via soft power. The rest, as they say, is history.

2.

In 1963, Avner was seconded by Adi Yaffe — who had just been promoted to become director of the prime minister’s office — as the prime minister’s English-language speechwriter. The prime minister at that time was Levi Eshkol who, in June of that year, found himself the unenviable position of succeeding the father of the nation, David Ben-Gurion, as both prime minister and minister of defence. Eshkol’s opponents — which included Ben-Gurion himself — accused him of being ‘an utter neophyte in matters of cabinet command’. This point, Avner concedes, ‘was partially true’.

Avner was quick to learn, however, ‘that this utterly likeable man was an accessible and easygoing chief, with no airs and graces’. Eshkol was unassuming, unaffected, and honest. He sprinkled his Hebrew with ‘droll Yiddishisms spoken in a lilting, singsong vernacular, charged with overtones and undertones and peppered with sentimentality, cupidity, and hilarity’. Ponderous, his leadership style ‘was that of a quiet persuader’: someone who invested hours in solicited opinions and talking problems though. He was ‘devoid’ of ‘personal vanity’ and cared little for material gain or keeping up appearances. Indeed, he cut something of a bland figure, something which in the end proved to be a political handicap: Eshkol ‘had no rhetoric, no eloquence, no charisma,’ Avner writes.

In the months prior to the 1967 Six-Day War, Avner accompanied Eshkol on a visit to Britain where the prime minister intended to meet with his fellow socialist Harold Wilson. Eshkol wanted Wilson to understand the dangers inherent in Syria’s designs on the Jordan River and intended to press him to sell Israel Chieftain tanks, brand new to the market having been brought into service in 1966. During their tête-à-tête at Downing Street, Eshkol made Wilson ‘visibly uncomfortable’ when he pointed out that Britain was arming Israel’s Arab neighbours with the very tank it desired, an act which in turn was endangering Israel’s national security. Israel never got the Chieftains it wanted:

Raising his hands in a dramatic gesture of reassurance, he began to speak elliptically about ‘silver linings’ and ‘military balances,’ and ‘Israeli pluck,’ and ‘never letting an old socialist comrade down’. And then, having exhausted his reassurances, he escorted his guest to the front door, where he bid him a fond farewell, waving a boisterous goodbye for the cameras to catch. Responding, Mr. Eshkol returned the wave with a forced smile and, entering his car, muttered to us in Yiddish under his breath, in a voice full of foreboding, ‘One talks and talks, and nobody listens.’

Eshkol appeared to prevaricate, equivocate, and engage in convoluted diplomacy on the eve of the Six-Day War, Avner records, but by the time of his death in office following a heart attack in 1969, Avner among others had come to see that Eshkol’s ‘gritty patience, nimble instincts and piercing shrewdness had ultimately convinced the world that Israel’s very survival had been at stake, and that the Jewish State had done all it could to avoid that war’. It was Eshkol, too, who laid the foundations for the strong political and military bond between Israel and the US after the Six-Day War, securing delivery of America’s F-4 Phantom II jet to replace Israel’s outmoded fleet of French aircraft just as the Soviet Union was arming Egypt and Syria to the teeth.

Eshkol was succeeded by Meir, who had left the Foreign Ministry in 1966; in the meantime, he had been Mapai’s party secretary. Avner began working for Meir in the autumn of 1972, heading the prime minister’s foreign press office. What distinguished her from the other Mapai and Labor prime ministers for whom Avner worked, he writes, is that Meir was in her way a true believer. In contrast perhaps to Ben-Gurion, of whom Tom Segev writes in his recent biography that all other priorities and ideologies were made subservient to Zionism, including socialism, her ‘bottom-line practical answers were rooted, first and foremost, in the creed of her Labor Zionist faith’.

Avner records that, while he was running the foreign press office, Meir engaged in a lengthy sit-down interview with Oriana Fallaci, during which the prime minister opened up to the Italian journalist once heralded for her interrogations of world leaders from Henry Kissinger to Colonel Gaddafi: ‘My feeling of anguish at leaving the kibbutz still goes through me like a needle. It was really a tragedy for me,’ she told her. When Fallaci asked Meir if this Israel, the Israel of the early 1970s, was the Israel she had dreamed of when she first came to Palestine as a pioneer, ‘Golda lit a cigarette, and blowing smoke through her nostrils, sighed,’ Avner recalls:

No, this is not the Israel I dreamed of. I naively thought that in a Jewish State there would not be all the evils that afflict other societies — theft, murder, prostitution. It’s something that breaks my heart. On the other hand, speaking as a Jewish socialist, Israel is more than I could ever have dreamed of, because the realization of Zionism is part of my socialism. Justice for the Jewish people has been the purpose of my life. Forty or fifty years ago I had no hopes that we Jews would ever have a sovereign state to call our own. Now that we have one, it doesn’t seem to me right to worry too much about its defects. We have a soil on which to put our feet, and that’s already a lot.

Her commitment to international socialism remained steadfast even as it became increasingly clear during the interbellum between 1967 and 1973 that Israel was alone in the world — the ‘perennial odd state out in the family of nations,’ as Avner writes, even among members of the Socialist International. ‘I look around me at the United Nations,’ he once heard her say, ‘and I think to myself, we have no family here. Israel is entirely alone here, less than popular, and certainly misunderstood. All we have to fall back on is our own Zionist faith. But why should that be? Why? Why?’ Strangely, Avner writes, ‘Golda Meir made no attempt to answer her own earth shattering question’. She resigned from office in 1974.

3.

Between his stints with Eshkol and Meir, Avner had been at the side of another prime minister — or rather, future prime minister — in the guise of Yitzhak Rabin. Following his retirement from the Israel Defence Forces (IDF), and although he possessed ‘few of the attributes commonly associated with diplomatic niceties,’ Rabin got himself dispatched by Eshkol to the US where he served as Israel’s man in Washington. There, Avner spent four ‘intense and highly rewarding’ years at Rabin’s side, during which ‘he was so parsimonious in his distribution of praise that the most gushing compliment he ever paid me was, “That’s okay”’. Nonetheless, Rabin is one of the two figures in The Prime Ministers whom Avner can be said to have most admired.

For Avner, Rabin initially posed something of a problem. In the company of family or his old comrades from the army, Rabin was ‘relaxed spontaneous, loving, even doting. But put him elsewhere and he invariably clammed up, and became introverted and shy’. Avner was responsible for drafting his English-language speeches and Rabin’s delivery is, not exactly unfairly, described as ‘wooden. His words failed to resonate. Emotional language was foreign to his terse style’. Yet Avner writes that Rabin had one indispensable quality as a leader that, in a sense, cannot be learnt: authenticity. Rabin, he says, ‘never work a mask’. He was who he was.

Rabin had grand ambitions for his time in Washington, as he outlined to Avner in their first meeting. He wanted to make sure Israel was ‘provided for in her defence requirements,’ coordinate a strategy for peace or a political settlement in the Middle East with the US, secure American financial support, and draw America into the Mideast theatre, using ‘its deterrent strength to prevent direct Soviet military intervention against Israel’ in the event of war. In order to achieve this, Rabin constructed a parallel diplomatic channel with the White House and in particular President Nixon (whom he thought was an antisemite, he once told Begin) and Kissinger, much to the chagrin of the foreign minister of the time, Abba Eban.

In Washington, Avner writes, Rabin acted ‘more like a minister of government than an official of the Foreign Ministry’:

In truth, no other envoy succeeded in cultivating so much trust and respect in so short a time among the highest levels of the Administration, the all-powerful media, the dominant string-pullers on Capitol Hill, and the influential Jewish organizations. In the course of Rabin’s five-year tenure he succeeded in turning a modest embassy into a prestigious address, so much so that in December 1972, as he wound down his tour of duty, Newsweek magazine crowned him ‘Ambassador of the Year.’

At that first meeting, Rabin also explained his vision for peace in the region, or more specifically, what he understood by ‘withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict’ and the establishment of ‘secure and recognised boundaries’, terms established by UN Security Council Resolution 242. Rabin desired ‘a Jewish and democratic state and not a binational state’, with boundaries that would ‘give Israel a maximum area of the biblical homeland with a maximum number of Jews whom we can maximally defend’. This was to be achieved via a gradualist approach; peace would not come in one fell swoop, but rather via disengagement, leading a diffusion of tensions, a building of trust, and then negotiations. ‘Measure these sentences against Rabin’s strategic record,’ Avner believes, ‘and you will find that he held to these guiding principles with absolute consistency for the rest of his life’.

After Rabin took the reins from Meir in 1974, he appointed Avner his adviser on Diaspora affairs and English-language speechwriter. At Rabin’s side, he witnessed what Avner measures as ‘his finest hour’: Operation Entebbe, which saved the lives of 102 of the 106 hostages hijacked by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. He also saw, at this moment of heightened tension in Israel, the conflict that would define Labor politics for the next 20 years and more: the tussle at the top between Rabin and Shimon Peres. Avner was very much a Rabin man: ‘I, personally, had little to do other than to write an occasional speech, letter, or position paper for Peres, who conducted whatever affairs of government he was engaged in either from the Cabinet Room … or from his ministry of defence office in Tel Aviv,’ he writes. ‘I confess that his propensity for hyperbole, poetry, and tautology got under my skin.’

As prime minister, Rabin’s great diplomatic achievement was the 1975 Sinai Interim Agreement: the prelude to Anwar Sadat’s overture to Israel, the Camp David Accords, and the Egypt-Israel peace treaty. Rabin mourned the departure of Kissinger, describing him to Avner as ‘the only secretary of state who ever truly understood the Israel-Arab conflict’. He didn’t quite know what to make of Jimmy Carter. ‘My fear is he’s going to embark on a misbegotten crusade to bring peace to the Holy Land and end up a misinformed meddler embroiling us all in an inferno,’ he told Avner, and a visit to Washington in March 1977 ended in acrimony and breakdown that threatened the gains made in US-Israel relations since the Six-Day War. In any case, Carter’s peace process and ambitions for the Middle East would soon be the business of another prime minister.

4.

Avner’s deep admiration for and loyalty to Rabin is clear, but the great love of The Prime Ministers is the man to whose ideology he was first introduced as a teenager in post-war Manchester — when the words ‘HANG THE JEW TERRORIST BEGIN’ were graffitied in blood red on the walls of his synagogue. ‘This was the thing about Begin: the mere mention of his name could arouse mighty and conflicting passions. Admirers adored him irrationally, and detractors loathed him irrationally. To some he was a great orator, to others a dangerous demagogue.’ And Avner firmly fell, head over heels, into the camp of irrational adoration.

In Manchester, Avner fell for the image of the fugitive and the ‘hardened and unyielding Irgun underground commander’. In the young Israel, one night at a rally in Tiberias when Anver was still a kibbutznik, he witnessed ‘a leader possessed of a unique, all-encompassing sense of Jewish history’. In the Knesset in the 1970s, Avner saw an ‘oratorical virtuoso whose mastery of style and pace could grasp and command any gathering’. And as prime minister, Begin was a leader after Avner’s own heart — a man whom he calls ‘the quintessential Jew’:

To me, an observant Jew, this was heady stuff indeed. I had served Levi Eshkol, Golda Meir and, until this morning, Yitzhak Rabin – all illustrious pioneers and idealistic Zionist diehards, but none of them possessed the depth of Menachem Begin’s reverence for Jewish tradition, his cosy acknowledgement of God, his familiarity with ancient customs, and his innate sense of Jewish kinship. He came from the heart of Jewish Poland, and though not strictly observant, was an old-school traditionalist with an infectious common touch which made Jews everywhere feel they really mattered.

Begin was brought into office by an electoral revolution, having spent almost 30 years largely in opposition — the image of the ‘iron-cored patriarch who was neutral in nothing’. He had a decent grasp of international affairs, but in other areas, including what Avner calls ‘the trivialities of diplomatic etiquette,’ Begin was in some ways ill-prepared for the task at hand. Avner writes, ‘Compared to the efficiency of the bureaus of the previous prime ministers I had served, Menachem Begin’s was a bit chaotic.’ Although he ‘took pride in thinking of himself as first among equals,’ Begin ‘ruled his cabinet with a rod of iron’. That cabinet, free from the clashes of personalities and interests that had defined the late Mapai years, was on the other hand ‘disciplined and leakproof,’ Avner says — at least in the beginning.

The Likudnik also rather quickly upended certain foreign policy doctrines held over from the Rabin era. While the former IDF man ‘had never permitted Israeli forces to become directly entangled in the Lebanese bloodbath for fear of being sucked into its infernal civil war, which had been ravaging the country since 1975,’ Begin saw it as Israel’s duty as a Jewish state to come to the aid of the Christian minority in Lebanon. Avner records Begin as telling the Chief of the General Staff, ‘We Jews know what it is to suffer as a minority. We shall come to the aid of any persecuted minority in the Middle East. The Christian world has abandoned the Lebanese Christians. We shall not abandon them.’ This was an ambition that would come with disastrous consequences.

Though he had worked for the Mapainiks Eshkol, Meir, and Rabin, Begin invited Avner to stay on as his English-language writer, though the task of penning speeches, letters, and memoranda for Begin was an altogether different and more complicated one. Eshkol had scalded Avner early on for his purple high style: ‘Boychik, if you don’t stop writing your fancy-schmancy nonsense and start writing what I want to say in the way I want to say it, I’ll find somebody else who will.’ Simplicity with Eshkol was key, as it was with Rabin who tasked Avner with rendering the economy, directness, and matter-of-factness of his Hebrew into English.

Begin, on the other hand, fancied himself as something of a wordsmith. He had learnt English during his days in the underground listening to the World Service on the wireless and ‘loved the BBC’s economy of style, its unexcitable precision, and its clarity of speech’. He was also, Avner writes, ‘a man of passionate polemic and gripping oratory. He loved the Knesset. He loved to debate. He loved to write. He loved to read. He loved to preach. He loved journalism. He loved letters’. Begin, thus, would prepare his English-language correspondence and it was Avner’s job, as the prime minister told him, to ‘polish my Polish English. You will be my Shakespeare. You will shakespearise it’.

His first term in office, when it came to diplomacy, was defined by peace between Israel and Egypt and Israel’s strategic withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula. On the Palestinian question, Begin remained intransigent; under his leadership, a Palestinian state would never come into being. The success of his first term (diplomatically-speaking, for his liberal economic reforms laid the groundwork for the inflationary crisis that, by 1984, would almost sink the Israeli economy) contrasts starkly with events after 1981, namely and especially the Lebanon War of 1982, a conflict which outlived Begin who died in 1992.

Begin was left exhausted not only by that war but the death of his wife, Aliza, in 1982, who had followed and stayed with him all through his years in the underground and the political wilderness. It is with great sadness that Avner recalls that, ‘without Aliza,’ Begin entered into a period of ‘physical decline, and his appetite was gone. The despair he felt at her death had been awful enough to endure, but it was cruelly compounded by a sense of lost opportunity and the disintegration of his political dreams about peace with Lebanon’.

By 1983, the year of his resignation, Begin was giving fewer interviews, meeting fewer people, attending fewer cabinet meetings, and engaging in fewer negotiations; ‘when he did participate, he tended to deal with matters more in the macro than in the micro, passively. Indeed, as time went by, he became less and less accessible to all but his closest advisers,’ Avner mourns. ‘I would bring him drafts of letters for approval a few times a week, but he hardly glanced at them. He appended his signature in a listless sort of way, and I would leave without saying a word.’ After Aliza’s death, Begin lost the very gift that had defined him: the power of speech.

Avner was one of thousands who attended Begin’s burial upon the Mount of Olives. ‘It was only when one of Menachem Begin’s old bodyguards recognised me that I was able to squeeze through the barrier that enclosed the burial site where the family stood. There, Benny Begin recited Kaddish and Yechiel Kadishai read the prayer for the tranquillity of the soul. And as many took turns to shovel earth into the grave, the aged Irgun veterans stood to attention and sang their old Irgun anthem in a final salute to their commander-in-chief who, for much of his life, had been a figure of controversy but who, on this day, was buried with a nation’s veneration.’