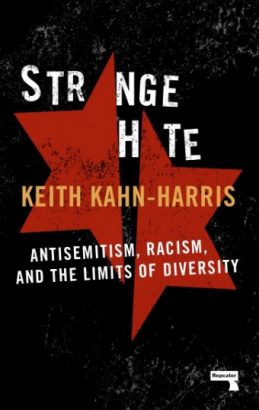

Keith Kahn-Harris’s book Strange Hate: Antisemitism, Racism and the Limits of Diversity is published in June 2019 by Repeater Books. In this essay he explores one theme of the book, the tendency of some on the left to divide Jews up into the ‘good’ ones and the ‘bad’ ones, the latter being those who ‘having been given the precious gift of absolute degradation and victimhood in the Holocaust, spoiled it all by seeking worldly power through statehood and upward mobility.’ He warns that those who take the view that ‘those Jews who embraced Zionism have betrayed their subaltern birthright’ may come to believe it is appropriate to remove certain kinds of Jews from anti-racist protection.

Like many British Jews, the Labour Party antisemitism controversy has consumed a lot of my attention and emotional energy over the last few years. From the beginning I was convinced that what I was witnessing was not antisemitism as I had previously understood it. I was struck how far most of those Labour Party members and supporters who had been caught up in the morass of antisemitism were also philosemites of a kind. Repeatedly, the Jewish people were divided into the ‘good’ – anti-Zionist – Jews and the ‘bad – Zionist – Jews. The former were hugged close, the latter rejected. As Steve Mackie, one Labour-supporting tweeter put it on 17 April 2019:

Genuine Jews, those with no hidden agenda are a real pleasure to be around. Zionists on the other hand should be banned from holding membership of any political party. Then made to return the land and assets to all Palestinians.

In my new book Strange Hate: Antisemitism, Racism and the Limits of Diversity, I call this kind of attitude to Jews ‘selective anti/semitism’. It is by no means confined to the anti-Zionist left. Increasingly we are seeing the good Jew/bad Jew distinction being made by the nationalist right who select Israel and rightist Zionists for love and liberal Jews for hate. Nonetheless, it is on the left that this process of selection is most advanced, because it has the deepest roots. Bolshevism and other Marxist traditions, in their eagerness to subsume Jews into the revolutionary process, left little or no room for Jews who would not join them. Indeed, a distrust of the Jewish connection to capital goes back as far as Marx. Nonetheless, it has been the ‘new left’ who, in the post-war period, have created the starkest disjuncture between good and bad Jews – stark because it has occurred during a period in which anti-racism became a central part of leftist practice and doctrine.

It takes an extraordinary sense of licence to select Jews for love and hatred in this way. I argue in my book that this presumption derives from disappointment, bewilderment and disgust at the course that Jews have followed in the post-war period. Having been given the precious gift of absolute degradation and victimhood in the Holocaust, Jews spoiled it all by seeking worldly power through statehood and upward mobility. This is not what the real wretched of the earth do. And those Jews who embraced Zionism have betrayed their subaltern birthright.

The corollary of this incomprehension at Jewish Zionism is a lack of consideration in speaking of and about those Jews (who constitute the majority of them) and a similar refusal to understand how opposition to Israel might be perceived by them. The message is something like this: if you continue to be Zionists, you are on your own.

This refusal to consider how Jewish Zionists might experience anti-Zionism has a history that long predates the accession of Jeremy Corbyn to the Labour Party leadership in 2015. In The Left’s Jewish Problem, Dave Rich argues with regard to 1970s attempts to ban university Jewish societies in the UK for their support for Zionism:

Those far-left activists pushing the anti-Zionist motions thought they were having just another political argument. For the majority of Jewish students, though, it was an attack on a fundamental part of their Jewishness.[1]

An appreciation of this fundamental difference in perception remains vitally important in understanding more recent controversies over antisemitism on the left and in pro-Palestinian activism. When Zionism is treated as a political ideology like any other – criticisable and open to contestation as other political ideologies are – then this will inevitably provoke, at the very least, deep insecurities amongst many Jews and a perception that such political contestation is either intrinsically antisemitic or opens the door to antisemitism.

This tension, this irreconcilable clash, tells us something about how ‘politics’ is often understood and enacted today. Setting aside the question of whether anti-Zionism is intrinsically antisemitic, one of the reasons why anti-Zionism so often ends up drawing on well-worn antisemitic tropes is that the political is often treated as an absolute space of contestation. To politically contest something is, all too often, to remove oneself from any self-imposed moral, ethical and social obligations towards political opponents. If supporters of the political ideology of Zionism are Jews, then so what? They can be abused, taunted and deliberately offended with the full range of discursive weaponry. If that weaponry recalls ‘classic’ antisemitic tropes, then so what? Politics is a war in which no quarter must be given.

This treatment of Zionism as only ever political is mirrored by the tendency among many Jews to treat it as beyond politics, as an indivisible part of Jewish identity. In my previous writing on divisions over Israel in Diaspora Jewish communities, I have argued that there has been a ‘forgetting’ of the political character of Zionism. The days are long past when Zionism was just one political ideology amongst others competing for Jewish political support. In the decades since 1967 and even before that, Israel became a source of broad consensus, a resource for stoking pride and consciousness-raising, in Jewish communities. If Diaspora Jewish Zionism is political it is less a politics that allows for the possibility of Jews not being Zionists; rather, it is a form of what Ilan Baron has called a ‘political obligation’ to have a relationship with Israel.[2]

That isn’t to say that Jewish Zionists in the UK do not engage with Israel in a political way. In the last few decades, British Jews have, cautiously, deepened their involvement with Israeli politics. There has been a growth of groups like Yachad and the New Israel Fund which intervene in deeply political questions of Israeli society and politics. Even the Board of Deputies expressed some measured concern at the recent Nation State Bill. And, of course, this very magazine provides a platform to diverse voices on the Israeli political spectrum.

Yet I would make the distinction between a guarded recognition of the inevitable political-ness of Israel – which is increasingly, although often reluctantly, recognised by UK Jewish Zionists – and a non-recognition of the political-ness of Zionism itself. In even the most liberal Zionist circles, the existence of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state is rarely up for questioning, still less negotiation. While questions about what Israel is and does might be raised with increasing frequency, questions about whether Israel should exist at all are almost always seen as out of bounds outside anti-Zionist Jewish circles.

In many ways, this kind of Zionist politics, which aspires to be apolitical, is a response to the form that anti-Zionism takes. When Jews seek to place Zionism beyond the realms of political contestation, they may well be fearing that exposing themselves to the political would be to expose themselves to antisemitic abuse – and, too often, those fears are justified. To be apolitical in this way is to seek to seek to create a fence around one’s hopes and dreams, to protect oneself from a brutal public sphere.

But however understandable this strategy might be, it is ultimately neither sustainable nor realistic. First of all, however much you might want to remove something from the public sphere of politics, in an age of multiple public platforms this cannot be successful. Zionist Jews may well seek to put the question of whether there should be a Jewish state beyond contestation, but we are no longer living in a world where this is possible, if it ever was. The wish to see Zionism put beyond question condemns Jews to a state of perpetual vulnerability. More than that, it strips Jews of the intellectual and political tools necessary to be able to argue for Zionism as a political ideology.

The fact remains that Zionism is political. This is actually a very banal point to make. Politics is simply the process through which humans manage the inevitable fact of competing interests, competing desires and competing visions of what it is to be human. To call something political is to recognise that it could be otherwise. The foundation of the modern state of Israel in 1948 and its subsequent actions emerged out of the choices and decisions that Jews and others made under varying degrees of constraint. Jews didn’t have to develop Zionism and they didn’t have to enact it in the way they did, however inevitable it might seem now or even however inevitable it might have felt at the time. And today Jews can decide to support the principle and reality of the Jewish state or not; they can perpetuate Zionism or abandon it.

Historically and sociologically (but not, perhaps, theologically), it is a grave mistake to see any particular constellation of human-created institutions as inviolate and fixed for eternity. Not only does such an apolitics negate any sense of agency, it actively disempowers those who believe in those institutions from making a successful defence of them. Ironically, Jewish Zionists stripped themselves of many of the tools necessary to make the case for Zionism once they decided that Zionism was beyond legitimate contestation.

The depoliticisation of Zionism has also created tensions and conflict within the Diaspora Jewish communities. While it may have been inevitable that the embrace of Zionism by the majority of members of most Diaspora Jewish communities led to conflict with those Jews who refused to do so, in recent years we have seen the spread of conflict inside the majoritarian Zionist camp itself. As I have argued elsewhere, in the last two-three decades, the old consensus that Jews should never criticise Israel in public has eroded. [3]To be a Zionist Jew and actively engage with the ‘internal’ politics of Israel (particularly its left-liberal variants) is to invite anger from those who insist that the only possible form of Diaspora Jewish Zionist politics is apolitically-political unconditional support.

Whether it is conflict over Israel in Diaspora Jewish communities, or controversies over antisemitism in the Labour Party, the same problem emerges time and time again: how should we deal with the entanglement of ethno-religious identity and politics? Both selective anti/semites and some Jewish Zionist activists deal with the problem by refusing to recognise it even exists; both assume an absolute separation. So for selective anti/semites it is of no consequence for political behaviour that many Jews see the Jewish state as central to their Jewish identities. For many Jewish Zionists, the Jewish state is to be removed from the political completely. And both strategies cannot succeed. Anti-Zionist activities face constant claims of antisemitism that mystify and outrage them; Jewish Zionists face constant disparagement of their most precious values that enrage and scare them.

This inability to face how politics and ethno-religious identity are entangled is the consequence of an implicit embrace of a vulgarised version of the Enlightenment model of politics: Politics takes place in a public sphere that free individuals enter, driven by reason and rationality, contesting with others in a civil process. The private sphere is where ethnicity, religion and other commitments are enacted, entirely separated from the political. That this bifurcated model has never corresponded much with reality and has been under sustained critique (from feminists as much as anyone) for decades, has not undermined its power and influence. It is, above all, very convenient to remove consideration of certain things from the political, to pretend that the public sphere can be a space of consequence-free struggle and the private sphere a space of uncontested commitments.

In Strange Hate I have tried to think through how it might be possible to break out of this sterile model. My starting point in this attempt has been to argue that, in the case of ethno-religious minorities at the very least, it is essential to accept the fact that politics and identities are intertwined. Further, to accept this requires accepting the fact that some minorities will hold tightly to political commitments that will be abhorrent to others. Crucially though, it is essential that a recognition of this should not mean the abandonment of anti-racism. This is what has happened too often on the left with regard to Jews – the recognition that most Jews are Zionists has sometimes meant that Jews are excluded from anti-racist protection – but it also applies to other ethno-religious minorities too. At some point, the left-wing struggle against Islamophobia may well be imperilled when the penny finally drops that the politics of Islamists is far from being left-wing. It therefore follows that anti-racism needs to be reconceived as a project of defending those whose politics, beliefs and identities may well be abhorrent to you.

Anti-racism, as I have attempted to define it, is a kind of self-sacrifice, acknowledging the hatefulness of the other but refusing to express that hate and even going further – fighting for the absolute right of others to be hateful. That means, as I appeal to anti-Zionist readers of my book (and I hope there will be plenty of them) fighting for the right of Jews to be as Zionist as they wish to be.

Why would any anti-Zionist want to do this? It seems unlikely that someone who sees the sufferings of the Palestinians as an urgent political priority could be tempted into fighting for the rights of apparently privileged Diaspora Jews to support the perpetrators of Palestinian suffering. However, there is a pot of gold at the end of my tiresome anti-racist rainbow. I suggest that an acknowledgement of the right of Jews to be Zionist might actually create the conditions under which Jews might acknowledge the political nature of Zionism. The only way in which Zionism could be an object of serious political debate involving Jews would be if Jews were secure enough to feel that exposing their most cherished components of identity to scrutiny would not end up destroying them. And this is why Zionist Jews might also be tempted to join anti-Zionists in this process. At the moment, Jews have little incentive to let go of their depoliticised Zionism, given the abusive way in which anti-Zionism is so often propagated. If the price for an anti-racism that was truly unconditional and unselective was to acknowledge that Jewish political choices are indeed contestable, might this not be worth it?

I actually think the vulgar Enlightenment model of politics does have things to recommend it. It would be nice to think that we could all argue out our differences without imperilling ourselves and our communities. The only way this can ever happen though is to make a conscious choice to do this in the full knowledge that it is fundamentally impossible. Perhaps an end to selective anti/semitism will have to be a kind of deliberate form of play-acting: Anti-Zionists speaking of and with those despicable Zionist Jews as if they actually respected their political identities; Zionist Jews pretending that they actually felt that Zionism was a political ideology like any other. This mutually self-interested and cynical delusion may be what a way out of the swamp we are currently sunk in might look like.

[1] Dave Rich, The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism, Biteback Publishing, 2016: 122

[2] Ilan Zvi Baron, Obligation in Exile: The Jewish Diaspora, Israel and Critique, 1 edition (Edinburgh University Press, 2015).

[3] Keith Kahn-Harris, Uncivil War: The Israel Conflict in the Jewish Community (David/Paul, 2016).