Ronnie Fraser was working in the Israel State archives when he came across a lengthy and confidential document in English (partly reproduced below) describing a meeting that took place on 29 January 1949 between Ernest Bevin, the British foreign secretary, and Joseph Linton, Israel’s Consul-General in London. Bevin had asked Linton to come to the Foreign Office so he could tell him formally that Britain had decided to give de facto recognition to the State of Israel. Their discussion raises a question mark over the accepted wisdom that Bevin was antisemitic and that his prejudice lay behind Britain’s delay in recognising Israel.

Was Ernest Bevin, Foreign Secretary in the 1945 British Labour Government, antisemitic? Many British Jews have certainly taken this view and many Israelis too. However, when undertaking research for my PhD about the British trade unions and their attitude to Israel, I started to question this view. I learnt that throughout the 1930s David Ben-Gurion and his colleagues had considered Bevin to be a powerful political friend who had spoken out on behalf of the Jews at the time of the Passfield White Paper in 1930. And as TUC President in 1937 Bevin made powerful speeches condemning the Nazis.[1] It was only in 1947; it seemed, as a member of Winston Churchill’s war cabinet, and then as foreign secretary in the post-war Labour government, that Bevin, struggling to solve the problems posed to British interests by the Palestine mandate, when a number of his actions towards the Jews could be interpreted as spiteful and even antisemitic. Notoriously, he sent the Jews aboard the ship Exodus back to Germany. Bevin remarked that Jewish survivors of Europe were ‘pushing to the front of the queue,’ and during the 1947 fuel crisis he made a joke about ‘Israelites’, implying that the Jews were involved in the black market.[2] His most infamous comment was that the people of America insisted 100,000 Jews be admitted to Palestine ‘because they do not want too many of them in New York.’[3]

Without doubt, in these years Bevin did put aside his pre-war warm feelings towards the Jews because his priority was the execution of the government’s Middle East policy, which was to maintain good relations with the Arab States in order to protect Britain’s vital political and economic interests in the region. The Foreign Office was also concerned with the likely effect on Muslims in India, still a British imperial possession, if Palestine became a Jewish state. It was in support of government policy that Bevin opposed not only the creation of a Jewish state and an Arab state in Palestine but also the unlimited immigration of Jewish refugees into Palestine.

Towards Recognition

When a government decides to recognise a new regime they have to decide what form recognition will take. De-jure recognition means that the regime qualifies as a state under international law and holds the rights and obligations that go with statehood, which usually signals a general willingness to enter into full diplomatic relations. De facto recognition also entails a willingness to carry on official relations, but may fall short of full diplomatic relations, such as the exchange of Ambassadors.

On 14 May 1948 when the British Mandate of Palestine ended, David Ben-Gurion announced the establishment of the State of Israel. Eleven minutes after the proclamation of independence, the American President Harry Truman granted de-facto recognition of Israel. Three days later, Russia granted Israel de-jure recognition. On the 10 June in answer to a question in Parliament as to whether the government proposed to recognise Israel, Bevin said that ‘we shall not make a decision on this matter until the situation becomes much clearer’. He denied that Britain had made representations to other countries urging the non-recognition of Israel, but said that the British attitude has been ‘explained’ to several governments. The following month he told MPs that the British Government did not at present recognise any body of persons as a de-jure government of Israel nor did it consider that the UN partition resolution obliged Britain to recognise the Jewish state. The British Government, Bevin said, would judge the Jewish case for recognition on its own merits, according to the normal criteria of international law. Britain’s attitude towards the question of recognising the State of Israel remained unchanged for the rest of the year.

In November 1948 Israel’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs appointed Joseph Linton, a British citizen, as Israel’s Consul-General in London even though he couldn’t speak Hebrew and had to write all his reports in English.[4] Bevin had considered establishing a British consulate in Tel Aviv to provide unofficial contact with the ‘Jewish authorities’ but was advised against it by the Foreign Office for fear of offending the Arabs. It was therefore left to the British Consul in Haifa, Cyril Marriot, who was inexperienced in Palestine affairs, to represent British interests ‘in the area’.[5]

The day after a debate in Parliament on 26 January 1949, The Guardian wrote ‘that the British Government has still not recognised the State of Israel. That is the one hard fact which stands out of Mr. Bevin’s speech’, and added, ‘recognition will come now so late, so reluctantly, so churlishly that it will pass almost unnoticed. What might once have roused hearts and won friends becomes at last an almost empty gesture…’[6]

After the debate, which had gone badly for him, Bevin arranged on Saturday 29 January a coordinated announcement of both Britain’s de facto and Australia’s de Jure recognition of Israel. There is no evidence that Bevin chose the Jewish Sabbath for the announcement on purpose rather than the day before or the following Monday.

The Linton Memo

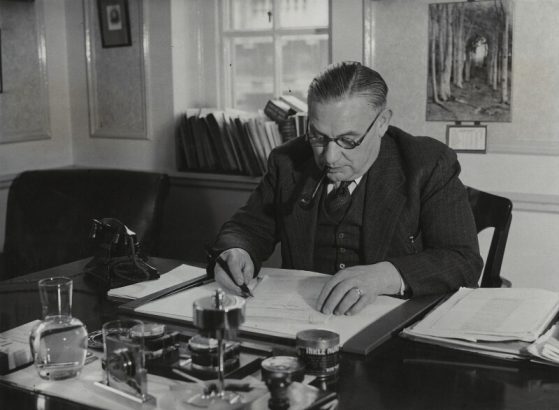

My scepticism towards the idea that Bevin was an antisemite was strengthened when I came across a confidential document in the Israel State archives, written in perfect English, which described in detail the meeting on 29 January 1949 between Bevin and Joseph Linton at which Britain confirmed it was giving de facto recognition to the State of Israel.[7] Although it was a Saturday, Joseph Linton, was busy at work in his office in the Israel Legation building in Manchester Square when he received a phone call to come to the Foreign Office. As he walked towards Downing Street, Linton remembered a story he had heard from Chaim Weizmann. Thirty-two years earlier, Weizmann and others had been waiting outside the Cabinet Offices while the British Cabinet was considering its attitude to Zionist aspirations. Sir Mark Sykes had come out and said ‘Gentlemen, it’s a boy!’ That boy was the Balfour Declaration. Linton was glad that today Bevin would report that it was, again, a boy.

Linton wrote up a lengthy memo of his meeting with Bevin that day. It is worth quoting at length for the insight it gives us into Bevin’s attitude to the Jewish state.

Mr. Burrows, the Head of the Eastern Department, had telephoned about 10.30 in the morning to say that H.M. Government had decided to give recognition to the Government of Israel, and that Mr. Bevin would be glad if I could call at the Foreign Office to see him at 12.30 p.m. I asked whether the statement would be issued after my interview with Mr. Bevin, and Mr. Burrows said that some difficulty had occurred because they wanted to issue the statement within an hour or so, but Mr. Bevin was heavily engaged and could see me only at 12.30. The statement, however, was very short, and he would give it to me over the telephone. Mr. Marriott would be seeing Mr. Shertok[8] about the same time. There were two further telephone calls from the Foreign Office, postponing the interview, first to 12.45, and later to 1 p.m.

Mr. Bevin was alone in his room, and after greetings he said that I had probably heard that they had just issued a statement giving de facto recognition to the Government of Israel. It was his wish to establish the friendliest relations between the two Governments. He would do everything he could to arrange for the exchange of representatives as soon as possible. He wanted to have direct contact with the Israeli Government through the Israeli Representation in London, and through H.M. Government’s Representative in Tel-Aviv. As far as I was concerned, whether I remained as Acting Representative, or was appointed Representative, or whether somebody else was appointed to London, he wanted to have direct contact. If I had any difficulties he would like me to come to see him, and he would do what he could to smooth them out. I should also keep in touch with Mr. Hector McNeil, and he would give the clearest instructions to the Heads of Departments concerned that they should always be ready to deal with any problems which we desired to raise.

I replied that I welcomed the decision of H.M. Government; I hoped that this decision would prove a step towards the establishment of normal and friendly relations between Israel and Great Britain. In spite of all that had happened there was a reservoir of sympathy and friendly feeling for the British people in Israel. That reservoir could be tapped. I also expressed the hope that, this decision would hasten the process of bringing peace to the Middle East. There should be no conflict of interests between Israel and Great Britain. With goodwill, many of the difficulties could be resolved, and the peace which would result would be of advantage not only to Israel but to Britain, the Arab States, and indeed to the world as a whole.

Bevin then turned to Linton and said that he would like to assure him that, in spite of all the froth in the press and elsewhere, he had never had any prejudice against Israel. He had had to carry with him a great many people and it was not easy for a Foreign Secretary at the centre of a great Empire. He explained that Israel had had in the past two days recognition from a substantial number of countries and that it was no accident that it had happened just now, and we could draw our own conclusions from it. Bevin then asked Linton for an assurance that he could talk to him freely and off the record, without any danger of leakages. After Linton had given him this assurance Bevin said that he could tell him confidentially ‘that we would not now have much opposition from India, though Pakistan was still adamant.’ He thought that Israel had not lost much by Britain waiting with her recognition.

Linton replied saying that he ‘had been in New York at the time when the Jewish State was proclaimed, and after America and Russia had given us their recognition, many of us had felt disappointed that Britain had not followed suit.’ Bevin replied saying that he appreciated that, ‘but it had not been easy to arrange it. America had been in touch with him on many things, but they had not told him that they intended to give immediate recognition. It had even come as a surprise to many of the Americans[9] at Lake Success.’[10]

He continued by saying that ‘the Palestine problem had been a long and difficult story, but he was very glad now that it was being settled. The Arabs had not been in a proper mood at that time, but the psychological moment had now come. He hoped that there would be no more fighting, and that it would be possible to bring about peace.’

Bevin then mentioned the contentious issue of the internment camps in Cyprus which the Labour government had established in August 1946 for Jewish ‘illegal’ immigrants; the majority of whom were Holocaust survivors. Some 28,000 out of the 53,510 Jews were still interned when the State of Israel was declared and the British had released them gradually at the rate of 1,500 internees a month. At the time of their meeting there were still several thousand internees living in the camps, the last of whom arrived in Israel 12 days later on 11 February 1949.

He told Linton that ‘he was glad that he had been able to arrange for the Jews in Cyprus to go. One of the difficulties’, he explained, ‘was that he had been asked to stop people of military age from leaving Cyprus, as a means of inducing the Arabs to agree to the first Truce. But recently, during the talks in Paris, he had asked Mr. Hector McNeil to get into touch with the Acting Mediator to see whether a way could not be found out of the difficulty in which he had been involved.’[11]

Bevin then added that he was arranging for Jews in other territories under British control or administration to be able to leave. He was referring to the wide-scale protests across the Arab world that had taken place after the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine had been approved in November 1947, and following Israel’s declaration of independence in May 1948. He admitted to Linton that he had not known that there was any trouble in Aden, and had only heard about it in Parliament during the debate. He promised Linton he would take it up at once with the Colonial Secretary. Linton explained to Bevin that 82 Jews had died in three days of violence in December 1947 when Aden’s Jewish community was violently attacked by Muslim rioters.[12] He then took the opportunity to ask that similar facilities should be given to the Jews in Tripoli and in other parts of North Africa which were under British control. He explained that the riots in Tripoli had begun In June 1948 a month after the war of independence had started and, unlike the 1945 Tripoli pogrom when more than 140 Jews were killed, the Jewish community was prepared and had fought back against the rioters, however 15 Jews had lost their lives and 280 Jewish homes had been destroyed.[13]

The conversation then turned to other matters when Bevin spoke about the difficulties in the past of doing anything tangible with regard to the Palestine problem.

He remarked at one stage that I probably did not know him. I said that we had met before on a number of occasions during the informal discussions which we had with him and Mr. Creech-Jones, when I was a member of the delegation headed by Mr. Ben-Gurion. Mr. Bevin said that there had been one or two occasions when he had thought he might be able to come to some settlement with us, but somehow or other it had not come off. He repeated that he would like to have direct dealings with the Israeli Government and that I should convey that to Mr. Shertok. He would like to avoid the intermediary of other Jewish bodies,[14] Members of Parliament and other individuals. I said that of course there were some Jewish problems which were not the direct concern of the Israeli Government and in which some Jewish bodies were interested; and they would no doubt be coming to the Foreign Secretary about them. Mr Bevin said that what he had had in mind, of course, was questions which concerned Palestine and Israeli problems.

When Mr. Bevin mentioned the prospects of peace, I said that I hoped would use his influence in the direction of helping to reach a successful outcome of the direct talks with the Arab States, so that we and the Arab States could return to our peaceful pursuits, and we could intensify our work of reconstruction. Mr Bevin said that he was much interested economic development in the Middle East; he had some ideas about it, and some of them of might be of interest to us.

Before Linton left, Bevin again repeated that he should keep in touch with him and Hector McNeil and the Eastern Department. Linton said that ‘I would like to take this opportunity of expressing my appreciation of the friendly way in which members of the Eastern Department had received me; I realised that it had not always been easy for them, because I was somewhat of a ghost, and it is not easy to deal with apparitions. I had tried not to embarrass them, and I must say that whenever I had made a request, I had always received a friendly hearing, whether they had been able to grant it or not. Mr. Bevin said that now that the position had been regularised he felt sure that there would be good relations between us.’

Israel had to wait another 15 months before Britain officially conferred de jure recognition to Israel on 28 April 1950. Once again Bevin made a simultaneous announcement, linking Britain’s recognition of Israel with that of her recognition of the annexation by Transjordan of the Arab part of Palestine.

Bevin’s primary reason for taking two years to recognise Israel, when it only took America minutes, was because Britain needed to rebuild her position in the region as the Arab defeat had a catastrophic effect on British influence there, with many Arabs blaming Britain for Israel’s creation. British policy towards Israel has always been decided by national self-interest and her wider Middle East policy was determined by her need for the friendship of key Arab states, as well as regular oil supplies. Britain’s relations with Israel came second and did not improve until 1958 when the Iraqi revolution threatened to destabilise Jordan. Both Israel and Britain then saw advantages in co-operating. This change in policy enabled Britain to sell military hardware to Israel and it was the start of new era of Anglo-Israeli relations.

While Linton’s report gives us an insight into the world of diplomacy, he did not reveal what he thought of Bevin. One who did was Israel’s first ambassador to Britain, Eliahu Elath. He wrote after his first meeting with Bevin in September 1950 that Bevin had struck him as ‘determined, powerful and cunning’. After his second meeting he noted that Bevin’s ‘pronounced fanatical nature and his characteristic of being vindictive and bearing a grudge against whoever does not accept his opinions, marked his attitude towards persons and issues.’[15]

Bevin was a superb politician and as Foreign Secretary he was a pragmatist who put his country before his personal feelings, but was he an antisemite? That remains an open question.

References

[1] Joseph Gorny, The British Labour Movement and Zionism 1917-1948, p. 171-2.

[2] Ian Hernon, Antisemitism and the Left, p. 111.

[3] Report of the 1946 Labour Conference p. 165.

[4] 1 September 1949, Israel State archives, file 2412/9.

[5] 16 June 1948, National Archives, FO371/68666.

[6] ‘Palestine’, the Guardian, 27 January 1949.

[7] Note of Interview with E Bevin 29 January 1949, Israel State Archives, File HZ37/5.

[8] Moshe Shertok was one of the signatories of Israel’s Declaration of Independence. He officially changed his surname from Shertok to Sharett when he was appointed Israel’s first Foreign minister. In 1956 when David Ben-Gurion retired, Sharett succeeded him as Prime Minister.

[9] The Americans Bevin had referred to as being surprised were George C. Marshall, the Secretary of State, and the State Department which had opposed President Truman’s decision to recognise Israel.

[10] From 1947 to 1952, part of the Sperry Gyroscope plant at Lake Success, Long Island, was used as the temporary headquarters of the United Nations while its new headquarters building in New York City was being built.

[11] The role of the UN Mediator was to negotiate armistice agreements with Israel, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Ralph J. Bunche was appointed as Acting Mediator after the assassination of the Mediator, Count Folke Bernadotte, in September 1948.

[12] At the conclusion of Israel’s War of Independence in 1949 Yemen changed its policy to allow Jewish emigration, despite the objections from the Arab League. Between June 1949 and September 1950 the Jewish Agency brought 49,000 Yemini Jews including 1,500 Jews from Aden to Israel.

[13] Between 1948 and 1951 over 30,000 Jews left Libya for Israel.

[14] The Jewish bodies Bevin is referring to are the English Zionist Federation, the World Jewish Congress and the Jewish Agency.

[15] Legation diary, 5 September 1950, Israel State Archives, File HZ 39/2 and Report of meeting with Bevin (Hebrew original), 26 November 1950, Israel State Archives, file 37/1.

Without belaboring the point, Bevin was anti-Zionistin his policies and at times was anti-Semitic. From The Bevin enigma: what motivated Ernest Bevin’s opposition to the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine

RAPHAEL LANGHAM (https://www.jstor.org/stable/41806170):-

“In May 1948 he remarked, to loud cheers in the House of Commons, that “We must also remember the Arabs’ side of the case – there are, after all, no Arabs in the House” This was seen as a jibe at the twenty-eight Jewish MPs. Later the same month, in answer to a question in the House, Bevin replied: “We must remember the British sergeants were not hanged from the tree by Arabs”. Three months later, on 3 August 1948 in a conversation with James McDonald, the first American ambassador to Israel, Bevin remarked that “the Jews were treating the Arab refugees as they themselves had been treated by the Nazis”.

From Robert Wistrich’s ‘Blood Libel to Boycott’;

“Despite the Holocaust, antisemitic attitudes had, if anything, grown worse in official and Army circles, even resonating at the highest levels of the British government. The first American ambassador to Israel, James G. McDonald, writing in his diary on 3 August 1948, was aghast at the “blazing hatred” of Labour’s Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin for “the Jews, the Israelis, the Israeli government” as well as for the new U.S. president Harry S. Truman. Richard Crossman, a young Labour MP who knew Bevin intimately, concluded in 1947 that British policy in Palestine was excessively influenced by “one man’s determination to teach the Jews a lesson.” (‘A Nation Reborn’ Richard Crossman 1960)

See Natan Aridan book, Britain, Israel and Anglo-Jewry, 1949-1957 (London, Routledge, 2004); “Anglo-Jewry and the State of Israel: Defining the Relationship, 1948-1956” Israel Studies, 10.1, Spring 2005.