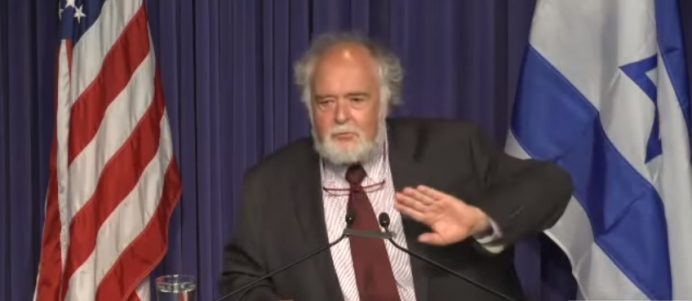

Yair Hirschfeld was a key architect of the Oslo Accords and is now the Director General of the Economic Cooperation Foundation (ECF) in Tel Aviv. In 2014 he published his seminal book Track-Two Diplomacy: Toward An Israeli-Palestinian Solution, 1978-2014.[1] The book not only traces the tortuous path of negotiations since 1978, but also offers a rich and compelling personal account of the highs and lows of a distinguished career. With Oslo forming its centrepiece, every phase of the peace process is analysed and evaluated, and what impresses most is the seriousness with which the Israeli team approached each negotiation. Oslo, it is clear, wasn’t a stroke of luck, the fortunate product of good chemistry or of the will and authority of one particular leader. It was the result of years of painstaking collective work, of mining the positives from failure, of learning from mistakes, and of slowly, tenaciously building a framework which set out a clear zone of agreement that both sides could sign up to.

As the CEO of BICOM I was delighted to have the opportunity to interview Yair at the offices of the ECF in Tel Aviv. I expected him to be downbeat, given the absence of top-level negotiations. Instead, he was full of energy and even optimism about what can be achieved. We explored his thoughts on the peace process, the lessons of Oslo, and of what the future might hold for Israeli-Palestinian relations. I began by asking him about the current situation.

Part 1: The state of the peace process today

Yair Hirschfeld: Given present conditions nobody today can speak about finalising a permanent status agreement. The gaps are far too wide. There’s no legitimacy there, no leadership, nothing that you really need. But you can move ahead on state-building. And we are working on this. There are very strong teams working on security. The Palestinians have started to understand that they are too weak to defend themselves and take responsibility for security. There has to be a certain Israeli control, one way or the other, in the Jordan Valley. Now we’re working on ways and means – how to do this without interfering with Palestinian sovereignty.

There is a lot happening on civil society. You have the division of the West Bank into areas A, B and C. A is the towns, B is the villages, and C is the rest. C is 60 per cent of the West Bank. If there’s no major economic development in Area C, then there’s no Palestinian state. At the moment there are difficulties, there is little understanding, and the Palestinians have taken an everything-or-nothing approach. We’ve got 50 projects which can be done in Area C. We have the Israeli Security Authority, officials in the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Finance trying to work on this. There’s the beginning of a very serious dialogue. One breakthrough is that while the Quartet powers (United States, UN, the European Union and Russia) have hitherto always asked to go to the endgame first – which we told Kerry at the beginning was a major mistake – since September 2015, the Quartet have said ‘let’s move forward with state-building and whatever can be done in order to preserve the two-state solution.’

So, you’ve got state-building, security, civil society and, number four, the regional approach. There’s a lot going on with the regional approach. There’s a lot of talking to the Saudis and others; how do you get a regional support structure? And there’s a fifth component – a discussion with the religious leadership and a discussion between the religious Jewish leadership and the Islamic leadership. Rabbi Michael Melchior is doing wonderful work there. (See the Fathom interview with Rabbi Melchior here.)

James Sorene: And all this is going on now, as ongoing track two activities?

YH: State-building is moving from track two to track one and a half. The officials are looking into state-building. On security it is track two, but it’s together with the Americans. On the religious component there’s Rabbi Melchior, who did unbelievable work. Things have calmed down in Jerusalem due mainly to his dialogue with Islamic leaders. He does the most impressive work you can imagine.

Part 2: Learning the lessons of Oslo

JS: Some people believe that Oslo happened out of the blue in 1993, but your book makes it clear that negotiations had been happening since the 1970s. The Camp David talks in 1978 kicked off a process and your book tells the incredible story of trial and error between 1978 and 1993. Why did it take so long to reach the breakthrough of 1993?

YH: The best answer is Churchill’s quip that a government reaches rational policies only after it exhausts all other alternatives. From a theoretical point of view, each side wants to get the maximum it can in negotiations, but you don’t know what that maximum is. You only know that after you’ve gone through several failures. Each sides tests the other; ‘what is the optimum I can get?’ There were different positions. You had the Israeli right who didn’t want Palestinian self-government. A second position did want it, but had serious security and political concerns – that position was found on both the Israeli and Palestinian side.

The basic Israeli position was to have a self-government agreement with the Palestinians, negotiated with the Jordanians. Most of Israel’s security concerns are very hard to deal with if a Palestinian state is established with full sovereignty and territory. There’s no strategic depth there. You can do it if there’s a connection with Jordan. So Rabin and Peres wanted a Jordanian-Palestinian confederation. If there was to be a Palestinian state then there would be a trilateral security arrangement: Jordan-Palestine-Israel. But the Palestinians wanted to do it without the Jordanians, so it took time to find out what was possible and what was not possible. The first option was to negotiate with the Egyptians, but that went down the pan. The second option was to try to get the Jordanians on board, which could have worked. King Hussein was willing to sign the ‘London Agreement’ in 1987, but Prime Minister Shamir opposed it. When this failed the Jordanians moved out and instead we got the Palestinian uprising [the First Intifada].

We then thought – and this was also for good strategic reasons – that we wanted to talk to the internal Palestinian leadership. If you speak to the internal leadership, you speak to the representatives of the Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza. If they want the end of the occupation, they need friendly relations with Israel. In many ways their well-being depends on cooperation with Israel. If you speak to the outside Palestinian leadership they want a return of the refugees to Haifa. So we wanted to talk to the internal leadership. It turned out that this was impossible – so we talked to the outside leadership on the condition that they come back in. One of the historical achievements of Oslo is that the external leadership became the internal leadership, representing the people in the West Bank and Gaza. And we actually can come to terms with Abbas as President of what will become the State of Palestine, not as the representative of the refugee community.

JS: What was the big breakthrough of Oslo? What was the big new thing you were offering? Was it recognition of the PLO?

YH: No. When you negotiate, as a rule, you have your own interests in mind. We have to understand the interests of the other side, but you’re fighting for your own people. On the Israeli side the decisive change was the principle of gradualism: that we should have a gradual approach, a source of authority, and control mechanisms necessary for security in the West Bank. This made it possible for it to go ahead. For the Palestinians, the major factor was that Peres and Rabin offered Arafat the option of coming back to Gaza. These were the two deal-making factors. We had an internal discussion about whether we should recognise the PLO or not, and Peres and me were actually against it. Yoel Singer made a strong argument in favour and this is what happened in the end.

JS: Would it have happened without that recognition of the PLO?

YH: Probably not.

JS: What is interesting about the Oslo story is that Yoel Singer just put recognition on the table. It wasn’t there before. Is that an argument for always having a lawyer in the room?

YH: It was a lawyer’s argument: if you sign an agreement, sign an agreement you’re responsible for. The politics were different: if you don’t recognise the PLO you still have an important negotiating card in your hand and the PA would be your counter-part.

JS: Could you elaborate a bit about what you said about the advantage to Israel when it came to control and security?

YH: The Camp David accords [of 1978] are very detailed. If you read the text Begin signed, and you understand the logic of negotiations, the only possible outcome of a negotiated agreement in line with the parameters laid down at Camp David, would be the establishment of a Palestinian state or a Jordanian-Palestinian Confederation. Thus, in the interim, Israel was supposed to withdraw the military government, to withdraw the civil administration, and to withdraw the army into specified security zones. That means Israel loses military control over the West Bank. Now, in the West Bank and in Gaza there are enough spoilers interested in causing major terror acts, so if Israel loses military control, there’s nobody there who can prevent this. There was a need to say ‘okay, for the time being we will stay there and you can develop your police force, your security forces, and together we can develop agreed terms of cooperation.’ But it has to be on a sliding scale: ‘You do more, we do less.’ It cannot be that we leave you to work alone.

JS: Did Oslo work because all the stars were aligned? The Soviet Union had just collapsed, the US administration was very engaged and at the most potent stage in its political cycle, there was an Israeli Prime Minister from the independence generation who was seen as ‘Mr. Security’, and there was all the creative thinking of your team that had been working on this for 20 years. All those things came together?

YH: All those things worked together – no question. But it wouldn’t have happened without the 15 years of work throughout. You needed the experience, the hard work, and the connections. Without all that, Oslo would never have happened. For example, as a result of our previous work, I had a document with all the Israeli positions and all the Palestinian positions, on every little issue. I had everything in front of me. If you know exactly what the in-depth positions of both sides are then you can think of bridging proposals. You can also see what is not possible.

JS: Can you tell me more about that document?

YH: Israeli-Palestinian negotiations started on 3 November 1991 in Madrid. They continued under Shamir and under Rabin. There were so many different issues. How does it relate to UN Resolution 242? What is the source of authority? What about water? How will we register the population? What is the police force going to look like? What will the Palestinian administration look like? Will there be a Palestinian legislative council? We had to cut through all those issues, by finding out how to bridge between the basic needs of both sides. If you’re not going into the details of each issue, it is very difficult to reach an understanding.

JS: If you could go back to 1993 and tell yourself ‘For God’s sake, do this’ to avoid a major mistake, what would that be?

YH: I would change three things. One I talked about in the book: religious actors on both sides were not part of the process and they should have been. I had a wonderful teacher, Professor Yehoshofat Harkabi, who wrote a book in 1986 called Israel’s Fateful Decisions. He argued that we must not allow this national conflict to become a religious conflict. So we knowingly excluded the religious guys. That was a mistake.

JS: And what could they have done?

YH: You need a sufficient majority to go ahead. And the legitimacy for moving ahead lay largely with the religious figures. We could have used different language; there’s no religious language in Oslo. Our second big failure was that the public relations were a total failure. Prime Minister Rabin had a tendency to oversell what we had achieved. Oslo was never a peace agreement. Oslo was an agreement on how to negotiate and move forwards towards peace. It created the wrong expectations. And our third mistake was to think that we could go for a permanent status agreement before creating the reality of a functioning two state situation on the ground.

JS: Do you mean you shouldn’t have set the 1999 deadline?

YH: No, we needed the 1999 deadline. That was fine. But we negotiated on track two what became known as the Beilin-Abu Mazen agreement and I wouldn’t do that again. It created the belief that it was possible to solve all outstanding core issues of conflict, Jerusalem, refugees, settlements, borders, security, finality of claims and end of conflict in all their complexities, on the basis of the negotiating principle that ‘nothing is agreed upon until everything is agreed upon,’ instead of moving ahead in promoting a process of ongoing conflict transformation and conflict resolution.. This concept of ‘everything or nothing’ strengthened a paradigm that was basically wrong. What I’m upset about is that Arafat told me so. He told me, ‘don’t go for it, don’t go for permanent status.’

JS: So he wanted it delayed?

YH: He wanted to solve issues as they came along and not be obliged to deal with all issues at one and the same time. Look, there’s a difference between American and Chinese thinking. Americans believe that for every problem there is a solution. By contrast, the Chinese are sure that whenever there is a solution, it is never really a solution; it is the beginning of a process. They think you have to look at the process and not at the solution. In this I am a strong supporter of the Chinese way of thinking and not the American way.

JS: Your book ends just before the Kerry process, why do you think it failed?

YH: When I wrote the book, the Kerry process was starting. When the book was published, we already knew it had totally failed. We often speak of the four-pillars of the peace process: Palestinian state-building, more security, support from regional actors, and taking care of the spoilers. Achieving progress on all four pillars can create the enabling conditions to reach a final agreement. But Kerry turned this all upside down. Instead of working on those four pillars and creating a reality necessary to move into the final negotiations, he wanted to have a framework of negotiations where you have all the issues solved. But if you start a building on the tenth floor and you’re not willing to build the foundation, and then the first, second, third and fourth floor, you will fail. We actually imploded and we are paying a very high price. So you ask me if I am critical of Kerry, the answer is yes.

JS: Also, Prime Minister Netanyahu was not negotiating with Mahmoud Abbas. Each was negotiating separately with Kerry, who was working with the different teams. That doesn’t seem like an effective process.

YH: It depends what you want. There are three different ways forward, I believe in two of them, but I don’t believe in the third. One is to try and reach full agreement. You can try to reach agreement; not on all outstanding issues, but on some specific issues. You can have an agreement to move from one phase to another. The Palestinian demand – and I think it makes sense – is to discuss territory and security first. You try to build trust and intimacy and move on to the more difficult issues.

A second way to move forward is to have coordinated, agreed upon, unilateral action with a lot of international and regional support. On security issues, there are many things we can do together without signing an agreement, also on water and other issues. But I think this is also something that is very valuable. It is not necessary to always have a document – we need change on the ground, not always a piece of paper. Then there’s the third option – purely unilateral action – which I think is a disaster.

Part 3: The future of the peace process

JS: What do you think is likely to happen over the next two years?

YH: One of three possibilities. The first is a dangerous trajectory: incitement, hate and lack of professionalism on both sides. This will lead to total disaster and we’re not far away from that. In both sides, both governments, there are some very destructive actors.

The second possibility is the more likely one. We stay above water, some things go badly while some things improve. Netanyahu is brilliant in doing this. It is a kind of poor conflict management; tactically it is very interesting to watch, but the problem gets worse.

And the third possibility is that there is substantial improvement and real hope that we can reach a settlement.

JS: What do we need to do to try and improve the chances of that third possibility?

YH: For one, trust-building activity. There is a donor conference in April and if it is successful – and we’re working hard on this – it will be important moment for trust building. If the Palestinian Authority (PA) goes bankrupt it is a ‘lose-lose’ for everybody. There’s a big effort to turn the donor conference into something constructive, to lead to the beginning of negotiations on territory and security. We also have to think about how to prevent another failure of negotiations. There are still gaps – there’s no Israeli government which can relocate 180,000 settlers for example.

JS: If we can build confidence and advance state-building and we do get back to negotiate the big issues of Jerusalem and refugees, do you think there is a zone of agreement on either issue?

YH: You have to make distinctions between conflict management, conflict transformation, and conflict resolution. Under present conditions the key is to engage in ‘conflict transformation.’ For example, in Jerusalem, the city in effect is divided. There are areas where neither Israeli nor Palestinian authority is being exercised and it causes criminal activity. There is a mutual interest to allow the PA to create a police, security and administrative presence there. In order to lay the foundations for a two-state solution, it is essential to expand Palestinian security and administrative capacities in areas B and C and to create a structure of good neighbourly relations.

JS: What about refugees?

YH: On refugees you have the Jordanian example. The Jordanians included the refugee camps in the municipal areas of cities close to the refugees. They’re taking care of the refugees, actually taking care of them. There are many things you can do.

JS: Which refugee camps are those? –

YH: All over Jordan. You can do this in the West Bank too. You can take care of them – you can include the refugee camps outside the PA area and put it into an administrative structure.

JS: To what extent will there be a gap in any conceivable negotiation between Israelis and Palestinians due to the Palestinian focus on questions of national narrative, justice and history?

YH: The basic argument that I make is this: ‘let’s change reality on the ground and create some common interests between the two peoples.’ There’s a lot of hate, mistrust and unfinished business. If you take the two examples where there has been major headway in negotiations – South Africa and Ireland – in both cases the so-called-underdogs, the ANC and Sinn Fein, made a major effort to understand the opinions of the other side, and that made progress possible. If the Palestinians don’t understand the basic essentials of what Israel needs, we won’t make progress. If they only talk of justice and history, that’s going to be a journey into demonisation and prejudice.

JS: If I was at the start of a negotiation and I said to you, ‘You’ve been doing this your whole life: tell me five things that I should do to succeed’, how would you reply?

YH: First, I’d tell you that you need a concept of mutual trust-building. Second, you should define what you already agree on. For example, on territory and security we agree on more than 70 per cent. So put down in an agreement what you agree upon and you use this in order to implement trust-building. Third, where there is agreement, implement. Fourth, work on bridging proposals on what you don’t agree upon. While you’re implementing, while you’re getting trust, while you’re getting legitimacy, while you’re moving forward on a two-state solution, while you’re building relations with third parties, while you’re fighting together against terror, while you’re creating a better atmosphere; work on bridging proposals. There are all kinds of innovative ideas on bridging proposals.

And I would tell you that it is important to ask the right questions. The question is not ‘what is the solution?’ The right questions are, ‘Do we want a two-state solution? How do I build a strong and effective and continuous Palestinian state? How do I build a strong Jewish and democratic state with equal civilian rights for all citizens? And how do I combine this with both sides recognising that Israel is the homeland of the Jewish people and Palestine the homeland of the Palestinian people.’

Fifth, you have to have agreement about how third parties can help you to implement what you’ve agreed upon, and how they can help you deal with the outstanding issues.

If you do all five, you have a package that can work.

[1] The US Institute of Peace defines track 2 diplomacy as ‘unofficial dialogue and problem-solving activities aimed at building relationships and encouraging new thinking that can inform the official process.’ USIP continue: ‘Track 2 activities typically involve influential academic, religious, and NGO leaders and other civil society actors who can interact more freely than high-ranking officials. Some analysts use the term track 1.5 to denote a situation in which official and non-official actors work together to resolve conflicts.’

Comments are closed.