Fathom Editor’s Introductory Note. Sometimes it is hard to know what is the more alarming: the state of the humanities and social sciences in US higher education or the failure of mainstream America, including its foundations and donors, to do anything about it. Perhaps this will wake some people up. Cary Nelson is a former president of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP). His exhaustively detailed case study of the tweeting, teaching and scholarship of GWU’s Lara Sheehi documents the impact of faculty anti-Zionist, and arguably antisemitic, social media, publication, and classroom practice on Jewish and other Zionist students. The issues at stake are relevant to the increasing antisemitic anti-Zionism found at universities worldwide. The astonishing material evidence presented here, plus the fact of documented student complaints, mean the case is exemplary, not least regarding the shameful victim-blaming of the GWU administration and of some professional bodies. Nelson’s argument should be studied throughout Higher Education, and not just in the USA. Finally, perhaps the case forces a question many of us have been avoiding: without fundamental change, is an alternative network of educational institutions now needed? How much longer can academics with intellectual integrity, students with independence and curiosity, parents who care for the quality of their children’s educational experience and donors who do not want their money to be spent on political indoctrination and antisemitic anti-Zionist pedagogy continue to support what many universities are becoming? (Alan Johnson, Editor of Fathom)

And that’s why I open the first class of the first semester reminding my doctoral clinical students that psychology and psychiatry are white supremacist fields that works alongside capitalism to *create* debility and we’re implicated if this is disavowed (4/6/2021, 8:41:34 PM) Lara Sheehi

The militant revolutionary struggle not only disrupts, but also has the potential to overturn coloniality entirely—when the struggle is an individualistic practice, the structure is not disrupted; when it becomes a social program, a militant struggle for a new social order, all forms of oppression are intimately implicated. DISRUPT

Lara Sheehi, ‘Writing on the Wall’ (261)

Even before Lara Sheehi’s Fall 2022 required first-year graduate course in the George Washington University Professional Psychology Program began, some students had a hint of what might be in store for them.[1] They had watched several of the YouTube videos she made with her husband Stephen that summarise their shared goals as professionals and their dedication to unqualified condemnation of the Jewish state. The Sheehis had coauthored a 2022 book, Psychoanalysis Under Occupation: Practicing Resistance in Palestine, and had given a number of recorded interviews summarising and introducing the book upon its publication. The book presents case histories to demonstrate Israel’s destructive impact on Palestinian psychology, mounts a fierce attack on the Jewish state, and urges that psychoanalytic practice worldwide devote itself to political liberation.

For Lara Sheehi, that commitment encompasses not only substantial revisions of psychoanalytic theory but also a revolution in both how therapists are trained and how patients are treated. That is a large step from recognising the distinctive impact of social and political conditions on individual patients’ lives, a responsibility that much therapeutic training now endorses. As she urges in a book review, we must resist ‘the centrifugal force of normativity, of white supremacy, and of liberal humanism that works to shore up the individual at the expense of the collective’ (1392). As she declares in their joint ‘Against Alienation’ interview, you ‘cannot be objective’ as a clinician; you should ‘join the motherfucking struggle.’

Once the course was under way, students also accessed some of Lara Sheehi’s Instagram messages and her numerous tweets (her tag line was @blackflaghag). Uneasiness about the course began to spread. But even the Jewish students maintained an open mind and a positive attitude, hoping that Sheehi’s politics and prejudices would prove irrelevant and that their first experiences of the program would be beneficial. Unfortunately, the very first class session included an unsettling incident. Following widespread practice, the students took turns offering capsule biographies, with Sheehi making brief supportive comments on each. When it came to the student from Israel, she identified her country, and Sheehi responded ‘It’s not your fault you were born in Israel.’ From Sheehi’s perspective, this was both an instinctive rejection of the Jewish state and a humiliating form of kindness: the student would not be held personally responsible for her citizenship.

Moreover, there were innumerable tweets like ‘Palestinians have been telling us since its illegal inception that Israel is an ethnonationalist supremacist state whose very existence is built around ethnic purity to which they’ll go to any end to achieve’ (9/1/2019, 6:39 AM) and ‘FUCK ZIONISM, ZIONISTS, AND SETTLER COLONIALISM using Palestinian lives as examples of their boundless cruelty and power. Anyone who can’t yet get it, peddles ‘both sides’ bs and doesn’t denounce this persistent violence is complicit’ (10/24/2020, 11:48:18 AM). The syllabus declares that the course is designed to help students ‘begin to develop comfort in self-disclosure and self-exploration, in service of professional and clinical development.’ How much ‘comfort in self-disclosure’ Zionist students could anticipate is not difficult to estimate.

The students encountering these fanatical, vulgar, extremist tweets from their professor were first-year graduate students, brand new to the program. Twenty-four students were in the class, the entire cohort of new students in the program. There were no other students enrolled. The class included a Palestinian student who is opposed to Israel’s existence. There was also one Israel-born student, as well as others with family ties to Israel. In addition to the orientation events they attended, some inevitably socialised with one another. They could not easily shrug off the conclusion that being ‘complicit,’ whether as overt Zionists or silent witnesses, might have consequences for them in the Professional Psychology Program.

Although the two Sheehis teach at different universities, the married couple collaborate on projects and share many political opinions, including their views about Israelis, Palestinians, and the priorities for clinical training in the US. She was previously a Lebanese-Canadian dual citizen, but she lost the Canadian half when the law changed[2] and is now a Lebanese employed as an Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychology at George Washington; he is Sultan Qaboos bin Said Professor of Middle East Studies[3] and Director of the Decolonizing Humanities Project at William and Mary. They reside in Williamsburg, Virginia. Lara Sheehi also maintains a small private practice counseling patients as a licensed clinical psychologist. Unlike some of the clinicians who advised me about drafts of this essay, she is not a graduate of a psychoanalytic institute.

During the fall semester, Lara Sheehi’s teaching—which some students found antisemitic—gave rise to a heated controversy. Students raised their problems with GWU, but Sheehi issued retaliatory accusations against them. In her 2023 Electronic Intifada interview with Nora Barrows-Friedman, Sheehi points out that she had taught the diversity course for more than six years without facing a formal complaint. But she hadn’t yet produced a substantial body of hostile tweets in her first years. The Jewish students may have realised they should hide their beliefs when the tweets started to accumulate. Moreover, her coauthored anti-Zionist book was not available until late 2021. In the Electronic Intifada interview, she claims it is unfair to ‘collapse’ her scholarship with her teaching, despite the fact that in the same conversation she brags that her research is partly about how psychology should be taught. As I will show, she has one unified professional career whose parts fit together. As events unfolded, the university took her claims seriously while dismissing the student complaints.

This essay is focused in part on the controversy that has since erupted over Sheehi’s teaching and the university’s handling of the resultant student reports of antisemitism; these in turn became the basis of a formal Title VI complaint filed with the Office of Civil Rights of the US Department of Education on January 11, 2023. The complaint was filed on behalf of several female GWU students by StandWithUs, a nonprofit group dedicated to combatting antisemitism. In addition to GWU, StandWithUs has submitted briefs for students at Hunter College and UCLA. The entire affair has had increasing coverage from the national press, including by Ryan Quinn in Inside Higher Education. Aaron Bandler compares the competing accounts in Jewish Journal. Although I will be reviewing details of the complaint, my concern is also with the broader implications of Sheehi’s professional activities.

StandWithUs is one of several NGOs, among them the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law, that have filed DOE complaints on behalf of Jewish students. The Brandeis Center’s complaints include a persuasive one directed at my own campus, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. They have also filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on behalf of two Stanford University health professionals, including a psychiatrist. Jewish clinicians and staff members were pressured to participate in a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion program that demanded participants confess the benefits they accrued from their ‘white privilege,’ though the organisers declined to consider any of the effects of antisemitism (Dremann).

This essay offers a distinctive opportunity to document the combined impact of faculty anti-Zionist—and arguably antisemitic—social media, publication, and classroom practice on Jewish and other Zionist students. The issues at stake are thus relevant to increasing antisemitism at universities worldwide. But the material evidence here, plus the fact of documented student complaints, make this a model case that cannot easily be discounted, though it has been and will be by slander and flat denial. The essay proceeds through defined topics: first, Lara Sheehi’s extensive use of social media; then an account of her Fall 2022 class and GWU’s unwarranted disciplinary actions against her students; and finally an analysis of the major arguments in her coauthored book. Regarding those last two topics, I should add this: appalling as her tweets may be, as actionable as her conduct inside and outside the classroom may be, we still have a responsibility to determine whether her more presentable professional publications embody similar beliefs. The essay’s eight sections are:

I. LARA SHEEHI’S INDUSTRIOUS TWEETING

II.SHEEHI’S CLASS AND A VISITING LECTURER

III. HER JEWISH STUDENTS’ NIGHTMARE

IV. SHEEHI’S SELF-DEFENSE

V. A LARA SHEEHI CONVERSATION WITH HERSELF

VI. PSYCHOANALYSIS UNDER OCCUPATION: POLITICISING THERAPEUTIC CASE HISTORIES

VII. PSYCHOANALYSIS UNDER OCCUPATION: SHOULD PALESTINIANS CHOOSE VIOLENCE OR DIALOGUE?

VIII. CONCLUSION

The essay draws on confidential interviews conducted with and documents provided by participants in the GWU events. Sometimes it incorporates student diction (without quote marks) so that the narrative can have the flavor of those who experienced these events first-hand.

I. LARA SHEEHI’S INDUSTRIOUS TWEETING

Contrary to the policy articulated by the American Association of University Professors in 2015, a policy adopted over my objections as AAUP president, I believe that, while the right to post freely on social media is protected by academic freedom, the content of those messages is subject to professional evaluation and review when it falls within the areas of a faculty member’s teaching or research. Except for the recurring profanity of Lara Sheehi’s tweets, they match her publications’ relentless demonisation of Israel. Moreover, although we do not know whether the hateful character of the tweets led them to be taken up and distributed by algorithms, we do know that tweets expressing extreme hostility or moral outrage are a high priority for selection by Twitter’s algorithm and wide dissemination to those showing interest in the topics addressed. We also know that her tweets eventually affected her students, a fact that will be even more the case in the future. Several published essays or news stories quote her tweets or reproduce representative screen shots. The tweets are not the focus of the DOE complaint, but their effect on Sheehi’s reputation going forward will be significant. They also raise issues of broad professional concern that merit emphasis here. Indeed, Sheehi’s tweets offer a test case to use in deciding whether substantial social media activity in a faculty member’s areas of teaching or research should be part of a faculty profile and be subject to professional evaluation.

The story of the 2022 course—its conduct, impact, and consequences—has a continuing history. There were tensions early on over the issue of antisemitism. As the course proceeded, her social media messages made the rounds among some of the students enrolled, giving rise to increased consternation. As Yael Lerman, director of the StandWithUs legal department, revealed in a 16 February 2023, Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC) Zoom event, some students further along in the program eventually told the first-year students ‘We should have warned you about her,’ meaning Sheehi. One student suggested to me that students in the class have historically been hesitant to be open about their Jewish/Israeli identities and that this has kept them safe. In the Fall 2022 class, for whatever reason, students dared to be open about who they were. Conflicts arose.

Undergraduates often fail to find out much if anything about their professors and indeed are often not very interested in faculty careers and intellectual histories. But these were graduate students, young professionals destined in many cases to become clinicians. They understood that in some cases it was in their best interest to know a faculty member’s biases before submitting their writing for review or venturing contrary opinions in class. As first-year graduate students, they felt especially vulnerable and uncertain in assessing faculty political and professional beliefs. Since there were no more experienced and more confident senior students in the room, the power differential between the instructor and the students was particularly stark. The GWU course in question is the first of three in a required ‘Diversity’ sequence, all three of them taught by Sheehi. Whether it was wise to assign her to teach all three required diversity courses is a matter for others to decide, though some diversity in instructor views and approaches might have educational benefit.

That students eventually found their way to Lara Sheehi’s tweets is not surprising. The graduate students entering the program in 2022 were part of a generation well versed in social media. Lara Sheehi would later protest that her tweets were private and thus it was improper to share or make an issue of them; but that protest is difficult to credit, given that she had several thousand Twitter followers and that Twitter is not a platform on which anyone expects privacy. Her protest thus seems disingenuous, quite possibly designed to enlist support from a credulous anti-Zionist constituency and thereby distract from the character of the tweets themselves. The Institute of Contemporary Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis (ICP+P), in defending its invitation to Sheehi to deliver a lecture, distributed a statement in February 2023 stating that ‘We did not consider tweets, quoted without context, from a private account, to be fair game.’ Others have gone further and claimed that quoting her tweets ‘violated her privacy.’ That really is an absurdity. One might as well say ‘Yes, it’s true that she climbed the White House fence and ran across the lawn brandishing a gun, but we consider that a private action that should not be subject to public comment.’[4]

Her videos and increasingly visible tweets excoriating Israel and Zionism make it highly probable, going forward, that Jewish students supporting the Jewish state will feel chastised before the bell rings for the first class. Meanwhile, her tweets supporting boycotts and the BDS movement empower the anti-Zionist students in the program. That would include any determined critics of Israel among future Jewish students, a recognised constituency for some years; some of those students from other institutions have come to her defense. The key pedagogical point is that the tweets enable her to share her most aggressive political views without voicing them in the classroom, a clever strategy for an assistant professor. Perhaps she is aware that the American Association of University Professors in 2015 adopted a policy declaring that all faculty member postings on social media should be protected from any professional evaluation or consequences. Whether Sheehi will observe the same caution in distinguishing between classroom and social media platforms after receiving tenure remains to be seen. Whether she will ever begin tweeting again is equally unknowable.

Even the tweets that target specific individuals send a troubling message to students who identify with Israel. When the Black American activist Chloé Valery, who is Christian, tweeted a comment about Black Lives Matter, Lara Sheehi tweeted a public response: ‘Pathetic. You can’t be a ‘zioness’ and profess to have any ability to critically assess anything, ever. Thanks much ‘ (1/29/2018, 10:12:52 PM). It amounted to a message to all Zionists, student and non-student alike, whatever their gender. But she sometimes offered a more aggressive and generalised pronouncement as well: ‘YOU CANNOT BE A ZIONIST AND A FEMINIST AT THE SAME TIME’ (5/9/2021, 5:54:04 PM). Here and throughout I reproduce Sheehi’s use of capitalisation.

While Sheehi regularly condemned Israeli actions, she also tweeted against Israel’s allies and all who fail to accept her view of matters: ‘Zionism is literally predicated on settler-colonialism and the notion that a whole people is inferior and therefore worthy of extinction—my bad that I don’t think that’s progressive’ (10/15/2018, 9:52:59 PM). ‘I hope everyone sleeps blissfully tonight, except for all you motherfuckers who still contest whether Palestine is occupied. You sleep on a bed of nails, hell’s heat, and bed bugs’ (12/6/2017, 9:51:48 PM). As Sheehi makes clear repeatedly, Palestine for her runs from the river to the sea. The Jewish interlopers anywhere in Palestine are all settlers. The Jews in Tel Aviv are settlers.

As late as 2016, in ‘Enactments of otherness,’ the Sheehis together declared their support for a bi-national state, despite the fact that the occupation—’the psychological juggernaut that organizes Israeli and Palestinian inter-relations’ (91)—had, in their view, eliminated the possibility of ‘genuine inter-subjective reciprocity,’ that ‘shared sphere of dialogue where reciprocity and community transpire’(85, 84). As Lara Sheehi’s anti-Zionist tweets thereafter escalated in number, however, the couple apparently stopped expressing support for a political resolution. Palestine, they declare, belongs to the Arabs. Any movement toward ‘mutual recognition,’ they insist in ‘The settler’s town,’ ‘could only begin with the dismantling of oppressive settler-colonial structures including the ideological, political, social, and military infrastructure of Israel as a religio-national state’ (189).

Despite her claims to the contrary, claims echoed by her allies, Lara Sheehi’s numerous tweets were public for most of their life. Once they became a subject of public controversy in 2023, she toggled them to private, but the swarm of locusts had already hatched—10,000 of her own messages plus thousands more retweets distributed without comment. In January 2023, just before she very briefly made her Twitter account private and then deleted it entirely, a concerned group other than StandWithUs captured 9,776 of her tweets and created a file noting for each tweet whether it commented on another tweet, was written in reply to a tweet, or otherwise was simply a statement that originated entirely with her. That is the main file that I have used as a source, a file available as well to future students in the GWU program. Excluded are thousands of additional occasions when she retweeted without comment, although some of her retweets are available in separate files. Whenever she included a link with any of the 9,776 tweets, those links are in the file and in this essay.[5] The links provide the immediate context for the tweet. Sheehi is not the only faculty member to have eliminated their Twitter account entirely when they realised belatedly it might prove embarrassing or professionally damaging; what is unusual here is that her entire Twitter file was preserved. That gives us an analytic resource of exceptional relevance.

Sheehi received her doctorate in psychology from GWU in 2010.[6] That was the year she began using Twitter. The yearly total of tweets shows growth to a period of intensity from 2017 to 2020.[7] The years with fewer tweets may represent periods when she was mostly retweeting without comment, was spending more time on other platforms, or was simply less occupied with social media. If, for example, she was commenting on 2014’s Operation Protective Edge on another platform, this file will not tell us. But it provides us with a significant number of strong opinions, often in exactly the same fields in which she publishes and teaches. Perhaps it also gives us a portrait of how her mind works. I wouldn’t claim her tweets are unmediated and certainly not uncalculated, but they are less reservedly filtered than an essay for an academic publisher.

Some of the non-Jewish students may have been at first amused. Here was a faculty member for whom ‘Fuck,’ ‘You Fuck!’ and ‘You motherfucker’ seem to be her preferred rejoinders on many occasions. Putting aside, for a moment, the political content of the tweets, one is struck by her heavy, even relentless, use of profanity and vulgarity, sometimes directed at other people. A professor who shouted profane imprecations at random passersby might well lose her job. It is an astoundingly unprofessional discursive practice, even in an age of informality and iconoclasm. Virtually anyone she disagrees with or despises—and that means scores of people—became the subject of these formulaic curses.

Not that they were always likely to receive them—unless she was responding to one of their tweets or someone forwarded the message. But her 3,229 followers on Twitter would get them. That is not a terribly large number of followers by Twitter standards, but it puts to the lie her disingenuous claims to privacy. And whenever she responded to a message, her tweet would appear within the originating conversation, adding more to the total number of her message recipients.[8] A hermit working off the grid in a mountain cabin she was not. In 2017, she became an Assistant Professor at GWU, following a year and a half there as a lecturer, and was thus a faculty member engaged in teaching and research. Her tweets could now acquire a new audience. Indeed, that was the year her tweets increased in number, going from 43 to 1,411. They increased by hundreds more in 2018. As she approached a tenure decision, they declined. By then, however, her views were solidly embedded in the Twitterverse or in her students’ minds.

On first reading, these tweets, for all practical purposes, seem to have been delivered into a psychological mirror, messages to herself perhaps serving as forms of tension release. Compounding the problem, she is a faculty member supposedly dedicated to reasoned analysis; yet most of the objects of her ‘Fuck you’ declarations never receive further analysis or critique. She does not develop serious arguments. She curses someone and moves on to the next enemy. Given that she was necessarily aware of her audience, however, we cannot dismiss the fact that these tweets were a form of public performance by a university professor. That was entirely within her rights but hardly an exercise of good judgment. At times, her world seems divided between enemies and allies.

The astonishing volume of these aggressive and profane tweets makes them central to Lara Sheehi’s impact and legacy. If she did not choose to constrain her impulses and emphasise the arguments that could be separated from the profanity, she cannot expect others to clean up her social media rhetoric and offer it in a sanitised version that never existed. Other faculty occasionally vent with profanity on social media, but this is well beyond the typical practice. Once I begin discussing Psychoanalysis Under Occupation, which embodies the same perspectives without the same language, this essay will focus on her arguments. But the tweets, and their tone and attitude, are not only part of her professional profile; they overshadow and merge with her teaching. With her tweets now widely in circulation, we can state a general principle: students entering the classroom of a professor who tweets in such a manner cannot be expected to think the personality behind those tweets will be irrelevant to their classroom experience. You cannot repress the actual reality of the tweets without repressing the experience of the graduate students in her class. The tweets amount to annotations to her syllabus. The tweets also constitute the hate speech that underlies Psychoanalysis Under Occupation.

Sheehi’s generic retorts are mixed with others that represent concise political commentary within Twitter’s word limit: ‘FUCK THAT. Fuck this. He should have been released way before. Free Mumia NOW. #FreeAllPoliticalPrisoners’ (4/15/2020, 5:15:31 PM) is a straightforward example. In May 2018, during the protests along the Gaza border with Israel, US senator Bernie Sanders tweeted ‘Over 50 killed in Gaza today and 2,000 wounded, on top of the 41 killed and more than 9,000 wounded over the past weeks. This is a staggering toll. Hamas violence does not justify Israel firing on unarmed protesters.’ She responded: ‘You cowardly, spineless fuck. Had to throw Hamas in there right? Can’t just make a statement of support for Palestinians being massacred. 11 THOUSAND wounded over the month, almost 100 dead including kids and press. No amount of ‘socialism’ can shake Empire in your bones’ (5/14/2018, 2:16:52 PM). Similarly, when the Austrian politician Johannes Hahn tweeted ‘Very worried about the violence at the #Gaza/#Israeli border. Call for restraint of both sides,’ she reacted with ‘WHAT BOTH SIDES MOTHERFUCKER. One side OWNS the border. The other is prisoner. HOW IS THIS HARD’ (3/30/2018, 8:31:33 PM). There are thus thematic and political clusters of tweets. And some are a mix of targeted aggression with clumsy efforts at generalisation: ‘Nancy fucking Pelosi reading an Israeli poem to talk about Roe v Wade being overturned is so ridiculously on the nose it’s a parody. Settler colonial fascism always nods to settler colonial fascism in the most heavy-handed of ways’ (6/24/2022, 8:10:27 PM).

The recurrent ‘You fucking disgusting fascistic pieces of shit’ and its variants often have somewhat specific targets. There are also intensifiers, as in ‘Power to the mother f-cking resistance, especially in Palestine’ celebrating the Day of Rage (2/22/2011, 10:04:54 PM), or telling us how ‘fucking wonderful’ someone is, San Francisco State University’s Rabab Abdulhadi being an example. But at least as common are unmoored, increasingly free floating epithets, as in these from 2020: ‘Fucking weenie,’ ‘So shut your fucking gobs about China and Iran, oh, and the rest of the world, you jingoistic fucks,’ ‘Is there a way to hate this fucker even more?’ ‘SING IT FROM THE HIGHEST PEAK MOTHERFUCKERS.’

Although his tweets are not my subject, I should note that Stephen Sheehi also regularly drops the F-bomb on twitter. His 10 May 2021, tweet is printed as a column: ‘SHEIKH JARRAH HAS CALLED / AND WE RESPOND: / FUCK ZIONISM / FUCK APARTHEID / FUCK CAPITALISM / FUCK WHITE SUPREMACY / FUCK SETTLER COLONIALISM / FUCK MILITARY OCCUPATION / FUCK ISRAEL / FUCK FEAR / PALESTINE WILL BE FREE / BECAUSE WE RESIST / TOGETHER, WE WIN / TOGETHER.’ Stephen Sheehi holds a chair in Middle East Studies and is Faculty Director of the Decolonizing Humanities Project. Given that he has an administrative position and thus represents the university in an official capacity, it is remarkable that he exercises no restraint in his language, indeed that he embraces vulgarity.

If Lara’s[9] pattern of responding with an expletive first seems sophomoric, after a hundred or so examples it becomes more unsettling. There is a cumulative impact to several hundred ‘Fuck’s, more than a few ‘Fuck Fuck Fuck’s, and many variants thereof—’Guess the fuck what, coming into this decade with the same motherfucking gumption to fuck it all up. The politic of refusal is the only way to create space in our world, the only way for me to sustain alignment and integrity. Get ready motherfuckers, it only gets better’ (1/1/2020, 1:08:50 PM). At that point, one really does not know what to think. But cheerful anticipation of the start of the semester was likely not the only emotion for some of those enrolled in what was a required course, mandated for the first-year psychology graduate students. Of the 9,776 tweets in the file I have used, there are 1,364 or 13.9 per cent that contain one or more variants of ‘fuck,’ information I offer with the assistance of Daniel Miehling of Indiana University’s Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism. He employed computational linguistics to produce the result.

That total, however, does not include her use of a hand emoji with the middle finger raised. Although she uses other emoji earlier, the ‘fuck’ emoji does not become an occasional feature of her tweets until 2020. In June of 2020 the Israeli social media influencer and conservative activist Hananya Naftali is implicated in a tweet that uses 45 of them. But a few months later there are just over a hundred and thirty of them in one tweet, lined up in five and a half neat rows, enough to field a company of soldiers ready to embark on a mission. Or we can think of this tweet, with its rows of emoji, as a concrete poem signed #blackflaghag.

Twenty per cent of the students in the course were Jewish, with identities partly based in Zionism. So a cascade of ‘Fuck Zionism’ and ‘Fuck Israel’ tweets or others demonising Israel persisting for years carried no amusement whatsoever. Indeed, those tweets often seemed suffused with rage, and the students increasingly saw themselves as among her targets.

For those students trying to make sense of the evidence at hand so far, a rabbit hole seemed to loom in the field beneath the plague of locusts. For the enraged tweeter had something of a split personality. Lara’s YouTube videos were all upbeat, indeed insistently cheerful, even sweet.[10] Her assertions about the deeply racist character of the Jewish state were delivered with a smile, like invitations to a birthday party. This soft-spoken gentleness was the performative affect she chose for her classroom political advocacy as well. It was dogmatic teaching delivered with contradictory affect, except when matters occasionally became more intense, when the façade began to crack, though she never risked displaying the rage of her tweets. Jewish students in the class found this disconnect between affect and content when she talked about Israel in videos uniquely unsettling. It can be considered a form of psychological gaslighting, designed to cause doubt both about the character of antisemitism and the character of the speaker.

Sheehi’s social media rage, on the other hand, was often enough just that: rage, offered in an illusion of its political efficacy: ‘MY RAGE CAN LIGHT A THOUSAND SUNS RIGHT NOW. Fuck ALL settlers’ ( 4/15/2022, 4:47:12 PM). But she eventually reflects on her own practice: ‘This is going to be a day of rage tweeting. I’m despondent’ (12/6/2017, 9:22:09 AM), ‘Scorched Earth is today’s modus operandi’ (12/6/2017, 11:10:46 AM). ‘How much rage must we carry day to day, every fucking place, big and small’ (8/7/2019, 8:26:35 PM)? Such reflection can also be sardonic: ‘Sorry to everyone today that will be inundated by my rage against the Israeli apartheid war machine and its ideological partner the grand ole USA’ (5/14/2018, 9:57:39 AM).

Sheehi was evidently proud of her invective. It sometimes seemed to constitute joyous rage. I take the changes she rings on the primary signifier—fuck, fucks. fucked, fucker, fuckery, fucking, fuckity, fuckface, fuckhead, fuckheads, fuckwad, fuckwit, Motherfucker, Motherfuckers, Motherfucking, fuckeveryword, and STFU (Shut the Fuck Up)—to speak to the celebratory element in her practice. Eventually, it apparently dawned on her this would not reliably produce joy in Mudville, especially Mudville University, but it took her twelve years to cancel the game. We were then well into extra innings.

II. SHEEHI’S CLASS AND A VISITING LECTURER

As the class progressed, those Jewish students who were sympathetic to Israel began to feel they were under assault. Yet the visceral challenge to Jewish students did not have to be part of the course’s core theoretical project. The course was a brief on behalf of Liberation Psychology, a body of theory that insists the only ethical way to practice psychoanalysis is for therapists to commit themselves to helping oppressed peoples liberate themselves. ‘How can one be a psychologist and pretend that the sociopolitical world doesn’t matter/isn’t relevant/doesn’t replicate itself in the room?!!!’ she tweeted (10/14/2018, 12:03:19 PM). ‘Join us in the struggle folks. The liberation struggle *must* include us clinicians, otherwise we’re colluding with oppression. There is no other way’ (1/26/2022, 7:52:06 PM).

For her students that meant not only understanding the social forces promoting injustice but also learning to resist them. The theory of liberation psychology evolved in Latin America, but only its more recent northern incarnation has acquired an anti-Zionist imperative. The 2020 handbook issued by the American Psychological Association—Liberation Psychology: Theory, Method, Practice, and Social Justice—does not mention either Israel or Zionism, though it does discuss antisemitism. But Sheehi was already prepared. As early as 2016 in Division 39’s newsletter, she proposed a slogan, ‘Let’s liberate Palestine with Psychoanalysis,’ in a piece titled ‘The Road to Psychoanalysis Runs Through Jerusalem.’ Two years later, in ‘Palestine is a Four-Letter Word,’ she dedicated herself ‘to bring Palestine to the forefront against the crushing weight of a dominantly entrenched Zionist ideology’ in psychoanalysis (30). And she offers a definition: Zionism is ‘an ideological formation based on the negation of the Palestinian people’ (29).

Nonetheless, liberation psychology can still be taught without committing to its anti-Zionist and antisemitic wing. Palestinian Liberation Theology, on the other hand, which developed in the 1970s and 1980s, has a decades-long history that is frequently antisemitic. Its founder, the Palestinian Anglian cleric Naim Stifan Ateek, has observed that ‘it seems to many of us that Jesus is on the cross again with thousands of crucified Palestinians around him. It only takes people of insight to see hundreds of thousands of crosses throughout the land. Palestinian men, women, and children being crucified. Palestine has become one huge Golgotha’ (quoted in Sandmel 278).

As the Sheehis make clear in Psychoanalysis Under Occupation and in various essays and social media pronouncements, they consider the world’s most compelling example of oppression to be the oppression of Palestinians by ‘the state currently known as Israel,’ the preferred designation throughout their book. They occasionally mention ‘what is now known as North America’ as well. For them, the Jews have absolutely no claim to either indigeneity or sovereignty in Israel. As early as their 2016 essay ‘Enactments of otherness,’ they made it clear that Palestinians are the one indigenous people with a direct relationship with the land, whereas the Jews’ relationship with the land is exclusively religious. In ‘The settler’s town is a strongly built town’ they condemn ‘the Zionist myth of Jewish indigenousness in the “Land of Israel”’ and refer to Palestinians as ‘the indigenous population of the settler state of Israel’ (186, 185).

Later, they emphasise Zionism’s fantasy character. Stephen discounts thousands of years of Jewish history in Israel, declaring in their joint interview with Rendering Unconscious that the Jewish Israelis have ‘a psychotic relationship to the land.’ He underlines the claim, by restating it, firmly grounding it in a hostile psychoanalytic formula for which he offers no evidence and no further explanation: ‘The connection to Palestine is one built on psychosis.’ It is an extraordinary claim, essentially a vicious slander and one his partner apparently endorses. Unsurprisingly, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illnesses, the American Psychiatric Association’s professional reference book on mental health issues, does not list Zionism as a form of mental illness. It is not merely irresponsible and unethical but professionally disqualifying for a clinician to claim otherwise. (ME: Exactly! The fucking state of fucking US academia. WTF. Fuck me, etc. )

An elective course embodying a less radical version of this agenda, a course arguing that the Jewish relationship to the land has a fantasy component, could be acceptable. But it would be very difficult to approve a course based on the ‘psychosis’ thesis without considerably more evidence. Making it a requirement for all students in the program would cross a line to become indoctrination. Worse still, Sheehi did not assign readings so as to stage a debate about this politicised version of psychoanalysis; she constructed a syllabus to advocate for it. The syllabus emphasises the need to ‘decolonize’ psychoanalysis by exposing its dominant ideology of privileged ‘whiteness.’ Once again, academic freedom would give an instructor the right to structure an elective that way, but professional ethics should have prohibited her doing so as a requirement. The program’s leadership and faculty should have intervened.

Sheehi’s course did not include a section on Israel. Instead, she criticised Israel and Zionism in passing. But the class did not miss the message in light of continuing classroom tensions, awareness of her videos and publications, and implications in some of the readings. As one student put it, most of the students ‘swallowed the Kool-Aid.’ They embraced the Liberation Psychology mission and its more recently acquired anti-Zionism and antisemitism. As a consequence, they were happy to join in Sheehi’s defense.

The class’s central focus on critiques of whiteness clearly implicated both Jews and Israelis. Thus Haddock-Lazala’s essay, required reading for students in the course—by a Puerto-Rican liberation psychologist—details the author’s struggles with both her Jewish analyst and a ‘White, Jewish, male professor,’ both of whom she finds insensitive and finally hostile. She tells the analyst that the colonial ‘situation in between [sic] Puerto Rico and the U.S. is like that of Israel and Palestine’ and adds ‘You are Israel and I am Palestine’ (89). The essay goes on to offer an extensive, enumerated critique of whiteness. Haddock-Lazala never explains the relevance of the analyst’s and the professor’s Jewish identity, but it hangs over the essay with its antisemitic implications and certainly would have troubled Sheehi’s Jewish students. Indeed, it raises the theme of Jews and Israel for all the readings about whiteness.

Sheehi had one more tactic to use in delivering the message of anti-Zionism. She invited ‘the incomparable Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian’ (2/6/2022, 5:54:58 PM) to give a guest lecture on 30 September 2022. Attendance was not required for students in the course, but a number of students attended and participated in a ninety-minute 3 October class discussion of the presentation. The Sheehis’ joint admiration for Shalhoub-Kevorkian and their support for her arguments is made clear in Psychoanalysis Under Occupation. They cite her repeatedly and recommend her ‘moving discussion on the psychic effects of communal dismemberment’ among Palestinians (34n60). They commend her for identifying ‘the ‘spiraling’ effects of violence experienced by Palestinians at the hands of the settler-colonial regime’ (51), a phrase they could well have composed themselves. They summarise and endorse Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s thesis about the Israeli mistreatment of Palestinian children in their first chapter and announce that her ‘presence is predominant’ in the next: ‘Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian has figured prominently in this chapter because her work demonstrates something particularly unique and important’ (104). Shalhoub-Kevorkian is thus central to two of the book’s four chapters. The lecturer served as an illustrious mouthpiece for Lara herself, not simply an opportunity for members of the GWU community to hear a well-known writer. There was no presentation of an alternative point-of-view. For Sheehi, Shalhoub-Kevorkian is an oracle who speaks the truth. So the Jewish students who support Israel had reason to conclude their professor had used her colleague from Jerusalem to convey the views they hold in common.

The program administrators have a taped copy of the lecture, but they would not grant their own students access to it. Student notes taken during Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s presentation record her relentless critique of all Israeli humanitarian services on the West bank and elsewhere. She displayed two slides depicting numerous examples of Israeli good works, like Lara Sheehi characterising them as cynical efforts to distract from Israeli crimes. In her Katie Halper interview, Sheehi updates her agreement with Shalhoub-Kevorkian by discrediting IsraAID projects, in this case the effort to help Turkey after its massive 2023 earthquake: ‘As Israel was saying ‘Oh, we’re helping out Turkey,’ and you bomb Syria the next day. Right? . . . ‘Mental Health Washing.’’ According to Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Israel ‘camouflages its oppressive power’ by its humanitarian work. Her slides includes her hand-drawn crude red circles drawn around Israeli flags displayed at aid projects, as if that proves they are merely propaganda efforts.

THREE OF SHALHOUB-KEVORKIAN’S SLIDES (Click to enlarge)

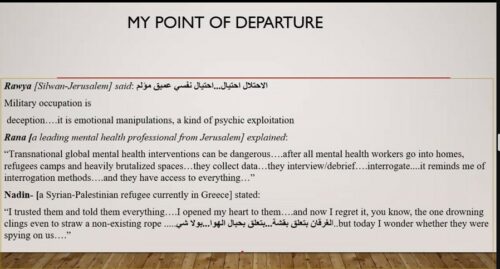

Another Shalhoub-Kevorkian slide was titled ‘MY POINT OF DEPARTURE.’ It was photographed by students during her presentation and shared with me. Three clinicians are quoted on the slide. One argues that ‘transnational global mental health interventions can be dangerous.’ ‘After all, mental health workers go into homes, refugee camps, and heavily brutalize spaces .. . they collect data . . . they interview/debrief . . . interrogate . .. and they have access to everything.’ Shalhoub-Kevorkian then amplifies the message, declaring that mental health work itself thus becomes a mode of occupation, ‘transforming killing into saving and murder into redemption.’ ‘We lament, we cry, we throw stones,’ she concluded, ‘That is our resistance.’

The Title VI complaint makes it clear how disturbed Jewish students were by the lecture. Instead of listening to their concerns, Sheehi in response worked hard to discredit them by impugning their character. Are we to take that as part of the goal for herself she describes to Electronic Intifada: ‘creating and uplifting the environment that I would want to see on a campus.’ Shalhoub-Kevorkian is an accomplished writer whose observations about Israel are often very harsh and accusatory. She is a Palestinian feminist and is the Lawrence D. Biele Chair in Law at the Faculty of Law-Institute of Criminology and the School of Social Work and Public Welfare at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. It is, however, one thing to read her offensive claim that Israelis test weapons systems against Palestinian children and quite another to encounter these and other accusations for the first time compressed into an oral presentation, where arguments lack the detail they have in print.

I consider Shalhoub-Kevorkian a political opponent, but she writes well, presents well-organised arguments, and needs to be addressed in kind. If you want students to be exposed to her ideas, assign one of her books for discussion, either following the lecture or in lieu of it. Simply bringing her in as a hired gun in the wake of an anti-Zionist video campaign is not good pedagogy. Neither the lecture nor one of her books should be assigned without also providing well-informed critical reviews of her work. It is too much to expect that even graduate students can readily supply counter arguments to positions as specific as hers. Indeed, ‘Diversity I’ is a training course for future therapists. There is no reason to assume those students know anything about Israeli government policies. As it is, Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s perspective was offered as uncontested truth. It is not surprising that Zionist students in these circumstances felt themselves not just challenged but under assault. Worse still, the students found the lecture to be antisemitic; once Sheehi seemed to endorse that antisemitism, the students were left with an impossible task: confront their professor’s antisemitism and face the consequences.

III. HER JEWISH STUDENTS’ NIGHTMARE

It is at that point that the full nightmare began. The StandWithUs complaint is presented in the neutral factual language appropriate to a legal brief, but it leaves no doubt about the traumatic ordeal the students endured. The students who were troubled by what happened were scrupulous in following the procedures recommended by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP). In class discussion, students registered their distress at Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s two-hour diatribe against Israel, the only country she singled out for criticism. In response, as the complaint details,

Professor Sheehi denied that what these students had experienced was antisemitism and dismissed their concerns. She expressed her (erroneous) view that ‘in no certain terms, anti-Zionism is not antisemitism,’ asserting that her position was not merely her opinion but a ‘non-negotiable truth’ like a ‘historical fact.’ Then she added, ‘Zionism in and of itself indicates that Jewish folks are different. There are many people who say that Zionism in and of itself is an antisemitic movement. Why? Because it locates that Jewish folks are that much more different that they need to have a space unto themselves. (6)

In view of Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s and Sheehi’s endorsements of political violence, an Israeli student asked people in the class to imagine what it was like to go to a bar and encounter a terrorist attack. Sheehi objected to the term ‘terrorist attack,’ insisting the term was Islamophobic, implying the Jewish students were racist.

The students were required to submit weekly journal entries expressing their personal feelings about the class, and they no longer felt comfortable giving them to Sheehi. Students spoke to another faculty member in the program seeking relief. The other professor offered to help, but later withdrew his offer. He suggested they meet with a college administrator. About that time the administration learned of the dispute and sent out a mass email. On October 26, 2022, a student met with a dean, explaining in detail how AAUP standards for student academic freedom and due process were being violated. The dean’s reply was remarkable: GWU was not bound by AAUP rules. The administration dismissed the student complaints without any real effort to investigate. The AAUP requires that charges be specified. It requires that accused students be able to confront their accusers. It supports their right to have an attorney or other advisor present. These and other basic principles of fairness were dismissed out of hand at various stages of GWU’s undue process.

Meanwhile, back in class students raised concerns about readings they considered antisemitic. Sheehi dismissed their arguments, and an unsympathetic student offered what had become a standard ‘woke’ rejoinder: the Jewish students were showing their ‘white fragility.’ Whiteness is a useful category of cultural analysis. The concept helped undermine the invisible, normative character of whiteness in the US and elsewhere, but it should not be hurled at Jews, let alone Israelis, as an accusation. The Nazis did not see Jews as part of the white race. Nor did many in the US for decades. Even in the contemporary environment, Jews are not universally considered unproblematically white. The radical right does not see them as genuinely white. Half of Israelis have families that fled from Arab countries, and many present visually as people of color. White supremacy is hardly a dominant factor in the long history of the Jews. In the psychoanalytic context, the term “white fragility” is used disparagingly to pathologize any attempt to resist the claim that whiteness is the all-encompassing, defining character of any people considered racially white. As Balázs Berkovits writes, applied to categorically to Jews, whiteness ‘assimilates the most persecuted minority in European history to the dominant majority, while downgrading the significance of antisemitism,’ denying it any structural social function. It places Jews within the dominant, oppressive majority. Applied to Israelis especially, it operates ‘in an explicitly accusatory manner’ (86, 100).

Sheehi should have disputed the white fragility claim at length. Indeed, she is personally experienced with racial ambiguity: ‘Despite my light complexion and blue eyes, I was often reminded of ‘my foreignness,’ told and retold, ‘you’re as black as the dirt we walk on’’ (‘unmatched twin’ 142). Instead, she closed the discussion by announcing in class that it was all in the hands of the dean. That meant the students’ complaint was no longer confidential; they consequently feared retaliation. It soon arrived in strengthened form. By mid-November, the Jewish students learned that Sheehi had been disparaging them in faculty groups, falsely claiming that they had called Shalhoub-Kevorkian herself a terrorist. This escalated to an allegation that the students were racist.

The result was that the students were subjected to disciplinary proceedings! Then matters became Orwellian. As the complaint specifies, ‘rather than provide the students with a statement of their offense, faculty have instead asked the students to describe to the faculty what they did wrong and what harm they caused’ (10). This amounted to a forced confession, one with a built-in threat that they could be judged unsuitable to become therapists if they did not cooperate. Confession would be part of remediation, which could lead to rehabilitation. As Carly Gammill of StandWithUs writes, ‘The students placed on remediation were put to an impossible test. To successfully complete the remediation, they were required to admit to conduct in which they had not engaged.’ It was time to seek more formal outside help. That was when StandWithUs was engaged. Several students, all women, as Lerner revealed, approached StandWithUs in December; one had been a StandWithUs intern and thus knew the staff and trusted them.

SWU’s Yael Lerman is clear that faculty antisemitic statements are protected. The problem, as she pointed out in her 16 February presentation, is when they cross a line into unlawful conduct like harassment. ‘Our complaint is about her discriminatory and retaliatory misconduct’ and ‘the failure of GW to take appropriate remedial action when they learned about it.’ She continues:

She can express whatever vitriol she has toward the Jewish state whenever she wants. She has that right. However, when that vitriol toward the Jewish state—in her classroom and outside the classroom—crosses the line into unlawful antisemitic conduct, she’s not allowed to do that. She’s not allowed to mistreat students in her class based on their Jewish and Israeli identity. She’s not allowed to retaliate against them when they stand up for themselves, and she’s not allowed to try to destroy their reputation to the university administration.

Based both on the complaint and on interviews with those involved, I am convinced that students were treated abusively and were seriously traumatised. The priority for StandWithUs was to get the baseless disciplinary process cancelled. After investigation, they drafted the brief over several weeks. As Lerner explained in her JCRC event, that put the disciplinary process put on hold, though the threat to the students persists.

Faced with a Title VI complaint, GWU decided on a face-saving gesture, announcing that they had hired an outside firm to investigate. The firm is Crowell & Moring, a large international law firm headquartered in Washington, DC. Their six hundred employees represent gas companies, pharmaceutical companies, companies engaged in toxic waste litigation, real estate projects, and tax disputes, among other corporate clients’ needs. Indeed, they have experience in defending institutions from civil rights allegations. It’s not like asking the Anti-Defamation League to look into the matter. It’s not clear the law firm has the requisite knowledge about antisemitism, though they have apparently interviewed GW students.

IV. SHEEHI’S SELF-DEFENSE

After StandWithUs filed its Title VI complaint on behalf of GWU students with the US Department of Education, Sheehi set about producing a remarkable self-defense,: ‘On Targeting an Arab Woman,’ published online in Counterpunch on 3 February 2023. As her title argues immediately, she has been targeted because of her ethnicity and race. Canadian psychoanalyst Jon Mills, in an Aero essay, concludes by suggesting ‘Sheehi should receive a fair hearing. But she should refrain from attempting to insulate herself from legitimate criticism by playing the race card.’ Her strategy has been effective. In the newsletter for Division 39 of the American Psychoanalytic Association, ‘Psychoanalysis for Social Responsibility,’ then president Carter J. Carter wrote that ‘what has transpired is a large-scale effort by white people to doxx, hobble, humiliate, and banish the first woman of color to run Division 39, one of the largest psychoanalytic organisations in the world. This is a mob of white people seeking to destroy a person of color and get away with it.’ I believe the DOE complaint demonstrates that this is untrue. Indeed, the whole controversy was triggered by Sheehi’s own behavior.

At a vulnerable moment in her professional life, as she approached a tenure decision, Sheehi chose to provoke a crisis. She knew what the alternative to abusing her Jewish students was: the very empathic pedagogy she lays out in her Counterpunch essay. But instead she poured gasoline on the fire. She had several opportunities to defuse the crisis; instead, she chose to escalate. It is difficult to understand why. Was she at risk professionally in ways I cannot detect? Her book has received reviews not merely glowing but sycophantic. A positive tenure decision seemed assured. She surely took a risk by exacerbating the crisis, but she also knew how to capitalise on it, quickly declaring herself a victim of political opposition and racial prejudice, potentially destined for martyrdom.

The GWU students whose perspectives inform this essay do not raise issues of race or ethnicity. They talk about the damage she did to them, but the operative noun is ‘teacher,’ not ‘Arab.’ Sheehi and her husband are both Lebanese, more specifically a Druze and a Maronite.[11] As Sheehi claims, ‘I have been targeted specifically because I am an Arab woman whose scholarship and activism advocates for Palestinians and, in the process, critiques Israeli settler-colonial Apartheid. Because I am an Arab, StandWithUs can casually parse key information to create an inflammatory narrative in place of facts, relying on anti-Arab prejudice which remains robust in the United States.’ I believe this is false. Whether Sheehi believes her accusation is impossible to say, but she certainly knew it was the most efficient way to organise international support. StandWithUs is committed to combatting antisemitism and defending Jewish identity, but they do not concern themselves with Sheehi’s ethnicity. Moreover, the complaint targets The George Washington University, one of several Title VI complaints filed by multiple NGOS against universities. These complaints allege administration indifference to antisemitism on campus and the creation of hostile climates for Jewish students. Sheehi is the example cited at length here, but if the university had done its duty, there would be no complaint.

Sheehi ends her Counterpunch piece with a fine flourish, an intersectional symphony of politically charged places and causes, her own implicitly added to the list:

Any anger that I express also pales in comparison to the violence of colonial, settler colonial, and imperial forces that have decimated the Middle East in the course of my lifetime. It pales in comparison to the internal and foreign policies of the Global North that have wreaked havoc on the most vulnerable people and their environments, especially in the Global South. It pales in comparison to the ways that language and comportment of women (especially women of color) are disciplined when they threaten to destabilize cisheteronormativity, patriarchy and whiteness. Even if decontextualized, the language of my tweets pale in comparison to the organized and systemic violence done to my siblings today from Jenin, to Nablus, to Jerusalem, from Pakistan, to Puerto Rico, to Iraq, to Kashmir, to Haiti, to Memphis, Jacksonville, Ferguson, Flint, Atlanta, Wet’suwet’en, Standing Rock, and all other spaces in which life is vibrant and deliberately targeted for swift erasure.

Sheehi defends her aggressive attacks by arguing that they pale in comparison to the real world violence carried out by Israel and other regimes. Obviously violent action, whether carried out by an army or a terrorist group, is a different from advocacy of violence. Sheehi’s comparison does not free her from responsibility for advocating violent action. Language is not more or less important than action. Indeed, we all know that aggressive language online too readily translates to violence on the street. She also argues that her aggressive rhetoric is frequently a response to deplorable actions by national governments. She insists that we need to evaluate her language in context. Ironically, the person who decontextualised some of her tweets is Sheehi herself when she deleted her Twitter account. But contexts for many others survive in the links that are integral parts of other tweets. When contexts are relevant I address them.

Another problem with her self-defense is that there is full warrant for selectively decontextualising many of her tweets. She reacts to a news event, an image, or a statement with a broad generalization, as she does in many tweets about Israel or Zionism. Those tweets were written as definitive general characterisations of political or cultural realities, and it would be irresponsible to treat them otherwise. They are stand-alone statements issued with great conviction, as she is well aware. She complains about being quoted out of context because she knows that will persuade potential allies that her critics have done something unprofessional or unethical, not because the complaint has any merit.

Indeed, there is another important context: the context of her identity and professional responsibilities. What does a reading of the nearly 10,000 tweets tell us about this faculty member who is on her way to becoming a national hero of the anti-Zionist movement? She has become a public figure who merits comment.

My interest follows from reading both her publications and her substantial body of her online communications. I am struck by the way Sheehi’s self-defense, like her YouTube performances, creates a persona radically different from the one on display in social media and in her publications. Her book is the most important example of the latter. A few weeks after news about the Title VI complaint broke, she launched a media campaign in her defense. Like the Counterpunch essay and the promotional videos for Psychoanalysis Under Occupation, the resulting videos at first present a figure of sweetness and light who has nary a hateful bone in her body, but they quickly become more aggressive. They include a substantial 6 February interview on Arab Talk with Jess & Jamal, a revealing 22 February interview with Electronic Intifada, and a still more hostile 28 February appearance on The Katie Halper Show.

Her self-defense includes expanded claims about the classroom debate that followed the Shalhoub-Kevorkian lecture. She tells us class discussion ‘took a very dark turn toward blatant racism,’ a turn, moreover, ‘that is unacceptable for clinicians in training.’ Clinicians, she emphasises, ‘have an ethical duty not to engage in racism.’ If it is true, as the students say, that they did no such thing, then this is a case of slander. As Gammill writes, ‘They never disparaged members of any racial or ethnic group.’ Sheehi has pushed the Shalhoub-Kevorkian story further by saying that Israel does not permit its own citizens to criticise the state, a particular absurdity given that Shalhoub-Kevorkian, an Israeli, does so throughout numerous publications and in public lectures. Moreover, Shalhoub-Kevorkian has a distinguished position at Israel’s most prestigious university. Nor is she by any means the only Israeli faculty member who is a severe critic of Israel. Their public statements and publications testify to Israel’s commitment to academic freedom. Sheehi is passionate in denouncing antisemitism on the far right, though she shows no awareness of its presence on the left, let alone in her own tweets. It is antisemitic to assert, as Sheehi does, that Jews have no authentic relation to the land and no right to a homeland there. Sheehi’s self-defense, I conclude, has in several respects made matters worse. As we will see in the next section, the Counterpunch essay highlights deep contradictions in her self-presentation.

V. A LARA SHEEHI CONVERSATION WITH HERSELF

The disparity between the two Lara Sheehis can be illustrated by inventing a conversation between her two different personas, which is what I will attempt to do here briefly. I italicise four quotations from her self-idealising Counterpunch essay, ‘On Targeting an Arab Woman,’ and indent a few of her many caustic tweets to show how much the two sets of texts contrast in both substance and tone. The noble sentiments in italics are in stark contrast with the harsh condemnations in the tweets that troubled some of her Jewish students:

1. Sheehi in Counterpunch: I do not single-out Jewish students, nor unduly and unfairly task them with holding their concerns in a cynical hierarchy of suffering.

Sheehi on Twitter in comparison:

– Yes, let’s please spend more money to unabashedly ‘celebrate’ an apartheid regime that indiscriminately executes medics and protestors. Solid message USA. Genocidal ideologies unite! https://t.co/a6K99M2sE4. (6/3/2018, 3:23:05 PM)

– You sick fucks. There is no way around it: this is not about ‘protection’ or arbitrary laws (made by the colonizer). It’s about sadism, humiliation, toxic power, and sociopathic policies intent on destroying a people and their psyche. (7/22/2019, 6:07:27 PM)

– They can’t tolerate even the semblance of freedom. This is what settler colonial apartheid does—any sign of Palestinian life is a direct threat to the legitimacy of the settler state. Remember this logic. (7/8/2021, 10:04:23 AM)

Comment on Passage # 1: Sheehi clearly accuses Israeli Jews and all Zionists of operating with a cynical hierarchy of suffering. She believes they discount Palestinian suffering and even their basic humanity. The tweets quoted here are some of a great many assertions to that effect.

2. Sheehi in Counterpunch: I went out of my way to explicitly distinguish between political Zionism (a political ideology and movement attached to a national state project) and spiritual Zionism (a religious movement within Judaism that has looked to Palestine as a locality for spiritual renewal while making no political claims to the land).

Sheehi on Twitter in comparison:

– Zionism is literally predicated on settler-colonialism and the notion that a whole people is inferior and therefore worthy of extinction—my bad that I don’t think that’s progressive (10/15/2018, 9:52:59 PM)

– Oh yes the big bad rocks, my god, how scary next to the self-identified ‘best military in the world.’ I’m shaking in my boots for them 🙄🙄🖕🏽🖕🏽

– Zionists are so far up their own asses they don’t see how this actually proves the point of undue and criminal force by occupying forces. (5/9/2021, 3:21:05 PM)

– Living in a world where white supremacy and Zionism, no matter how soft, constantly collide is to live in a world of INCESSANT gaslighting and one where you’re in protective overdrive. This isn’t in my fucking head, it’s real.(5/18/2022, 11:30:32 AM)

– And fuckers are still arguing about whether or not zionism is a form of fascist white supremacy. Ok. (10/11/2022, 10:01:00 AM)

– Zionist also means settler colonialism, period. (5/19/2021, 10:31:39 AM) [excerpt]

Comment on Passage #2: I know of no place in her publications where she discusses ‘spiritual Zionism.’ There has long been a version of Zionism that rejects national sovereignty for the Jewish people, but it is now an insignificant component of Israeli life and in the West represented mainly in the radical anti-Zionist left. For most Jews spiritual Zionism and the connection with the Jewish homeland are intertwined. Her distinction is thus rather cynical. The tweets show her hostile attitude toward the only Zionism that matters today, a Zionism committed to a Jewish state as a Jewish homeland.

3. Sheehi in Counterpunch: I teach them that as ethical clinicians we have the responsibility to criticize all state discourses without essentializing an entire people.

Sheehi on Twitter in comparison:

– The occupation of Palestine through Israeli settler colonialism is a tragedy beyond what can be imagined, read about, seen through a lens. It hits you in waves. I gave a training talk to clinicians today, they’re doing their best work, yet occupation is systemic and suffocating. (9/13/2018, 2:45:05 PM)

– It’s not fucking racism when resisting against an occupier with a single-minded wet dream of normalization and legitimacy. (1/13/2018, 8:20:34 PM)

– Sorry to everyone today that will be inundated by my rage against the Israeli apartheid war machine and it’s ideological partner the grand ole USA. (5/14/2018, 9:57:39 AM)

Comment on Passage # 3: She relentlessly generalizes about the Israeli people in her tweets and publications, essentializing them as brutal and inhumane. Her tweets and publications contradict the posture taken in the Counterpunch essay, as did Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s lecture.

4. Sheehi in Counterpunch: My pedagogical approach irrefutably contradicts the claims of identity-based targeting, as it is not reserved just for my Jewish or Israeli students. It is a contract that is made with all students, not as a matter of political agenda, but rather, a commitment to the field and to the wellbeing of our patients.

Sheehi on Twitter in comparison:

– But this is how colonization works: it cannot function properly if their victims are being restored so they murder with impunity those who dare facilitate healing https://t.co/VRzohqYZR1. (5/22/2018, 3:42:18 PM)

– Good morning to everyone except those who still think Israel is a democracy. 🖕🏽🖕🏽🖕🏽🖕🏽🖕🏽🖕🏽🖕🏽 (7/22/2019, 7:36:36 AM)

– This is why Palestinian children are treated as objects that can be abused, detained, tortured and killed. It’s a weaponization of racism to justify ethnic cleansing and state terror. You can say this person is extremist, but the same logic is baked into all settler colonialism. (8/22/2021, 12:30:03 PM)

– The apartheid state never rests. (1/17/2022, 10:07:01 AM)

Comment on Passage # 4: Contrary to Sheehi’s claim in ‘On Targeting an Arab Woman,’ her whole career is based on identity-based targeting. It is fundamental to her book.

Many other tweets could be added to the indented quotes, as could passages from their book.

VI. PSYCHOANALYSIS UNDER OCCUPATION: POLITICIZING THERAPEUTIC CASE HISTORIES

It is now time to shift gears and give due consideration to the coauthored book, Psychoanalysis Under Occupation: Practicing Resistance in Palestine (2021), that elaborates in detail the anti-Zionist passions that animated Lara Sheehi’s tweets for a decade. Published in 2022 as a relatively expensive hardback, not a trade book, it could only have limited circulation, but it has since been reprinted in paper and can have a wider audience among both faculty and students. If the views Lara Sheehi promotes in assertive tweets are to have any professional credibility, it should be found here.

Zionist settler colonialism in their view encompasses ‘the technologies of occupation, and the inchoate processes of enclosing and asphyxiating Palestinian communities’ (4). ‘Asphyxiation’ is one of the book’s most persistent and recurrent metaphors, referring to ‘the politics of asphyxiation imposed upon the Palestinian people, physically and psychologically’ (76). Thus the term is more than metaphoric. Asphyxiation imposes a kind of living death on Palestinians; it aims ‘to control how much and when they can breathe’ (12), literally killing many. That ultimate consequence permeates all daily life; ‘death is an ever-present condition of the necropolitical regime of power imposed upon Palestinians’ (19). The Israeli regime ‘intends Palestinians to die’ (8).

Several of Lara and Stephen Sheehis’ chapters are built around individual case histories of Palestinians who struggled with psychological problems. They draw on local clinicians’ accounts of patient histories, adding their own interpretations and conclusions. Their overall aim is to argue for the destructive impact of the Israeli occupation on Palestinian psychology and mental health. These case histories are the critical core of the book for a number of the clinicians I consulted—not only because they address the authors’ professional competence but because they reveal the therapeutic perils of combining anti-Zionism with a social justice agenda.[12]

There is a fundamental—and likely unresolvable—contradiction built into this agenda. The Sheehi’s political convictions lead them to see all Israelis, whatever their job titles, as undifferentiated, interchangeable agents of the occupation. In ‘The Islamophobic Normative Unconscious,’ she properly condemns the belief system that ‘collapses Islam into a monolithic entity with an essential potentiality for violence’ (162), but she embraces that very prejudice regarding Israelis. The pressures psychoanalysis might exert toward individuation have no impact there. Similarly, both as victims of Israeli oppression and as avatars of ‘resistance,’ Palestinians become interchangeable in their eyes. But here the pressures of their training—and of Lara Sheehi’s clinical practice—motivate them to see Palestinians as individuals. Much like social-justice therapy, with which liberation psychology partially overlaps, however, they are impelled to impose an identity-driven narrative on all Palestinians. As Sally Satel writes, ‘Instead of treating each client as a unique individual and working collaboratively, the social-justice therapist reduces them to avatars of gender, race and ethnicity.’ For the Sheehis instead there is continuing tension between individuation and political generalisation.

The following are three of the cases they summarise and interpret, followed by a fourth from an essay by Lara alone. None of these are patients with whom either Sheehi had personal contact. They were not Sheehi patients, nor were either of the Sheehis in a supervisory capacity with the therapists who did see these patients. The Sheehis interviewed the first three therapists, and Lara Sheehi may have spoken with the fourth. I have spoken with none of them, but we are all operating at degrees of removal from the patients themselves. The quotations here are from the Sheehi’s interpretations of the patient cases.

1 – Samar, a 40-year-old married woman, was treated both by a psychiatrist and by the clinical director of the Guidance and Training Center for the Child and Family in Bethlehem. Given anti-anxiety medication to alleviate her anxiety about death, she showed no improvement. She lived in a multigenerational family home dominated by men; she could not leave without their permission. ‘Her family, especially her brothers, refused to allow her to marry her true love.’ Her own family members beat him up, and he fled to the US. ‘Heartbroken, Samar accepted to marry another man, chosen for her by her family’ (1).[13] Sheehi, in her unidimensional perspective, minimises the fact that it was her relatives who physically assaulted the patient’s loved one. As one of the psychoanalysts who commented on my draft suggested, ‘those violent acts alone can be seen as sufficient cause for the patient’s internalized distress.’ Now married for 20 years with her own children, she no longer has sexual relations with her husband. Although Samar’s difficulties are rooted in the violence and rigidity of her family, the Sheehis find a way to place responsibility on Israeli security policy, in the form of the wall erected around parts of the West Bank two decades ago. In their account, Samar is drawn to young men she sees in public, though she is unable to act on the impulses. ‘The construction of the Apartheid Wall coincided with the beginning of her married life and so Samar also built a wall around herself and was unable to move in her inner world . . . . How could the Apartheid wall not become a symbol to what happened inside her . . .?’ (3). ‘If Samar’s desire is negated by the men around her, this violence is only assisted by the Apartheid regime that works in concert with toxic masculinity to limit her movement, and to constrain and contain her. As her selfhood was managed and contained by her male kin, this same selfhood remains a target of surveillance, control and activation for the Israeli occupation regime’ (4).

Rather than accept a challenge ‘to decipher if the Wall was a stand-in for the marriage or the marriage a stand-in for the Wall,’ the Sheehis conclude that ‘all forces of oppression work in concert, shored up by a settler-colonial project that is implicated in all psychic suffering.’ The Wall is apparently akin to a force multiplier. My own view is that Samar’s suffering originates with a patriarchal Palestinian culture that long predates the creation of the State of Israel. It is certainly possible that she also projected her feelings about family and community constraints onto her physical surroundings, including the separation barrier, but one set of factors is primary, the other at best secondary. It is not even clear that she thought of the Wall mainly as an Israeli presence; it may have functioned psychologically as another layer of her restrictive family home. The Sheehis report that her death anxiety disappeared after a year of therapy, but the Wall did not withdraw to facilitate the cure.

2 – ‘On August 29, 2017, Mohannad Younis, a 22-year-old promising short-story author, asphyxiated himself in Gaza City. He had twice attempted suicide before. ‘Reportedly, in the year before killing himself, both his paternal uncle and his father kept telling Mohannad that he was a failure even in committing suicide’ (78). He had asked his father to finance his education in Europe, but his father refused and disowned him. Israeli officials denied him an exit permit to study at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The Sheehis offer no explanation for the Israeli action. Nor do they raise the possibility there may have been one. For them, it is simply gratuitous cruelty. The father also refused to provide a dowry so Mohannad could marry. Meanwhile, his published stories were meeting with considerable acclaim.

‘It is not surprising,’ the Sheehis write, ‘that many read Mohannad’s suicide as an allegory of Gaza’s young generation’ (79). ‘We read that the Israeli siege of Gaza and Mohannad’s father represent a parallel process, one in which they replicate one another, each identifiable as distinctly suffocating forces’ (80). ‘We come to see the collusion between the father and occupation, between structures of oppression, patriarchy, and the right of self-determination’ (81). ‘His suicide was a taking of his own ‘breath’ . . . . Mohannad’s story symbolizes the suffocating assemblage of settler colonialism and its dialectics with family and internal dynamics’ (81). It seems we are once again in the world of Samar, where the family is the determining cause. Had Mohannad’s father supported him, he might well still be alive. But the Sheehis want to suggest an earlier causality; the father behaves as he does because of the influence of the occupation. ‘The father’s behavior replicates the operationalized psychotic process and psychopathic sadism of the occupation’ (82). ‘The father is the structural psychic means by which Israeli violence is internalized’ (83). But they operate not in the cliched model of universal castration, but rather in a shared project of denying the son his individuality.