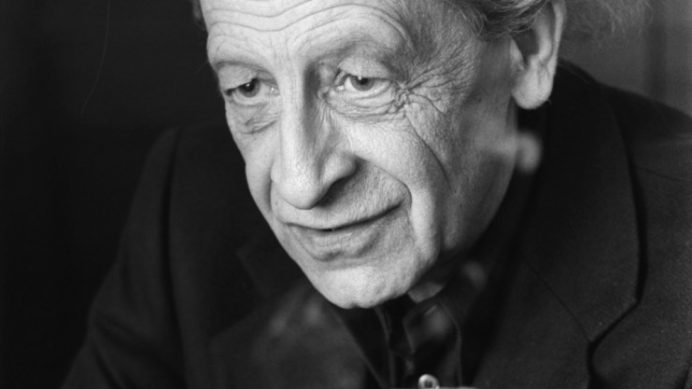

Jean Améry is best known as the author of At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities. Less well known are Améry’s writings from the 1960s and 1970s in which he warned that under the guise of anti-Zionism, ‘the old, wretched antisemitism ventures forth’ again in a distinctively ‘left-wing’ form. ‘Anyone who questions Israel’s right to exist is either too stupid to understand that he is contributing to or is intentionally promoting an über-Auschwitz,’ he wrote. Alvin H. Rosenfeld examines Améry’s legacy in advance of the publication of Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left, edited by Marlene Gallner, translated by Lars Fischer (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, forthcoming).

Antisemitism is repulsive wherever it appears, but its prominence on the left, where it often takes the form of an obsessive, demonising anti-Zionism, is especially abhorrent. Such passions were broadly on display in May, 2021, at the time of Israel’s latest war with Hamas. Over a period of eleven days, Hamas and Islamic Jihad targeted Israeli civilians with more than 4,300 rockets. When Israel struck back, it was fervently denounced as an aggressively racist, colonialist, apartheid, and uniquely criminal state. These slurs, long a formulaic part of Arab anti-Israel accusations, are firmly embedded in the political rhetoric of the anti-Israel left and were repeatedly used in May to defame the Jewish state, this in the name of peace, justice, and human rights. The tactic is malicious, but malice repeated often enough takes hold among some and creates a climate of ill will, albeit ill will disguised as virtue. What then follows in the wake of such maneuvers can be fearsome.

The phenomenon is not new, although it has become newly energised in our own day. To understand its presence within the political left, we can benefit by reconnecting with the writer Jean Améry, himself a long-time member of the left who, in his last years, devoted himself to exposing and denouncing the anti-Zionism of many of his erstwhile political allies.

Jean Améry is known to English readers today largely owing to a single book, At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities (1980). With the appearance of this work, first published in German in 1966 as Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne (‘Beyond Guilt and Atonement’), Améry established himself as one of the indispensable thinkers on the nature of Jewish fate and the complexities of Jewish identity during the Holocaust and beyond. A slim volume of only five essays, At the Mind’s Limits offers strikingly original insights into life and death in the Nazi camps and profound reflections on the anguished and enduring legacy of that terrifying time. Drawing on his own experiences as an inmate of a Belgian prison as well as his incarceration in three different camps, Améry’s autobiographical and philosophical writings on the ordeals he underwent are distinguished by a rare degree of intellectual vigor and moral courage. At their best, they rise to the level of the most penetrating work on the Holocaust by such other major essayists as Imre Kertész, Primo Levi, and Elie Wiesel.

To be a Jew, Améry wrote, was to be a dead man on leave, someone marked out to be murdered. That realisation came to him as early as 1935, when, as a student in Vienna, he first read the Nazi racial laws. The child of a Jewish father whom he never knew (he was killed as a soldier in World War I) and a Catholic mother, Améry, whose given name was Hans Maier, grew up in Austria with barely any connection to Judaism or any knowledge of himself as a Jew. All that changed with the advent of Nazi rule in Germany and the singling out of Jews as a pariah people. Whether he personally regarded himself as a Jew or not, the new racial laws defined him as one. In doing so, he realised, they put him under a death sentence. With a clear-eyed view of what was in store for him, he abandoned his native Austria for Belgium, where for a short time he carried out some minor tasks for the anti-Nazi resistance. When he was seized for these activities, it was soon discovered that he was guilty of a far more serious offense — that of being a Jew. As such, he was sent to prisons and camps in France and Belgium before being transported to Auschwitz, Dora, and Bergen-Belsen. The extremity of his experiences in these places marked him for the rest of his life and, over time, determined the course he would take as a writer: that of a ‘vehemently protesting Jew,’ or, as he sometimes described himself, a ‘catastrophe Jew.’

Améry’s mature writing career was brief — a mere 12 years — and, often in the form of rapidly written journalistic articles, focused much of his attention on prominent figures and events in contemporary European politics and culture. His most lasting work, though, returned him to his wartime experiences and took the form of essayistic reflections on the torments he underwent as a Jew under Nazi rule. He had managed to survive the worst of what he had been subjected to, yet he was never able to look on his victimisation as a thing of the past. He who was tortured remained tortured, he insisted. The Nazi crimes and the trauma that accompanied them were irrevocable.

The trauma intensified in his later years as he observed something he never expected to witness: the return of openly voiced antisemitic passions in German social and political life. Under the guise of anti-Zionism, ‘the old, wretched antisemitism ventures forth,’ as he ruefully noted in the preface to the second edition of At the Mind’s Limits. At anti-Israel rallies in German cities in the 1970s, Améry heard not only fierce denunciations of Zionism as ‘a global plague’ and ‘strike the Zionist dead — and make the East red’ but also repeated cries of ‘Death to the Jewish people.’ The fact that these primitive hatreds were voiced by young men and women of the left, his own political home, infuriated Améry. He had not expected to witness such a scandalous spectacle in post-war Germany, especially coming from people he had regarded as his friends and natural allies, but ‘the tide has turned. Again, an old-new antisemitism impudently raises its disgusting head, without raising indignation.’ Not one to remain passive in the face of such hostility, Améry stepped forth to voice his own indignation. ‘The political as well as Jewish Nazi victim, which I was and am, cannot be silent,’ he declared. And in essay after essay, he forcefully wrote in opposition to the old evil enacted by Hitler’s Germany and in protest against its rehabilitation in the form of a strident and threatening anti-Zionism.

Knowledge of Zionism was no more a part of Améry’s formative years in Austria than was knowledge of Judaism, and yet in his later years he became a passionate defender of Israel, especially against the country’s adversaries on the left. In this respect, he stood out among German-language authors of his time, for his voice as a public supporter of the Jewish state’s right to exist found few others to match it. In fact, he was the first to publicly denounce anti-Zionism as a new form of antisemitism in Germany.

The grounds for this stance were not fundamentally political or ideological in nature but existential. To a large extent, they were based in an awareness that antisemitism was an inherent part of European culture and persisted in the minds of many even after the end of Nazi rule. As he saw it, ‘the possibility cannot be ruled out that the systematic annihilation of large numbers of Jews could recur.’ Israel, he believed, was as sure a defense against such a fearsome recurrence as any the Jews could hope to have. And yet, since its birth, Israel was the target of militant opposition by Arab countries in the Middle East and, to his horror, by many in Europe whose anti-Zionism was trumpeted as a necessary and even ‘virtuous’ political stance.

Améry’s commitment to Zionism, therefore, was in many ways a reaction to the anti-Zionism of his own day, which, he was convinced, was only the latest manifestation of an age-old and probably ineradicable hostility to Jews. He was deeply wary of it, particularly as he feared it was becoming socially acceptable again. ‘Hatred of Israel, if left to run its course …., can only serve the evil and unjust scourge of antisemitism,’ he wrote. He was dismayed by that prospect, and he fought against it vigorously, often by invoking the hatreds that had been directed against him as a Jew and whose scars he bore literally on his own flesh. And so he denounced it in the strongest of terms: ‘Anyone who questions Israel’s right to exist is either too stupid to understand that he is contributing to or is intentionally promoting an über-Auschwitz.’

The origins of Améry’s anti-anti-Zionism are easy to decipher. He had almost no firsthand knowledge of Israel, did not speak or understand its language, was unacquainted with its culture, and had no particular connection to its dominant religion. A proud humanist and liberal thinker, he had no interest in Judaism and had little sympathy for what he called its ‘superstitions.’ He visited Israel only once, and that was for just a brief stay late in his life. What made him the uncompromising Israel advocate that he became was not cultural affinities or nationalist sentiment but the Auschwitz numbers tattooed on his left forearm. The message this brand conveyed to him was potent and mattered far more than whatever wisdom he might find in the Torah and Talmud. Simply stated, that deeply inscribed, never-to-be-eradicated message is that every Jew alive, whether he knew it or not, could be set upon, abandoned, cast out, murdered. He was fond of quoting Sartre — ’What the anti-Semite wishes, what he prepares for, is the death of the Jew’ — but Améry really needed no outside authority to support his conviction that all Jews everywhere were potentially imperiled. He was also convinced that whenever and wherever the lives of Jews were once again endangered, ‘there is a place on earth that would take them in, no matter what.’ That place was Israel. For this reason, Améry was entirely open about his devotion to the Jewish state: ‘The existence of no other state means more to me … Israel must under all circumstances be preserved.’

It shocked him, therefore, that Israel, a sanctuary for victims of past persecution and a necessary asylum for would-be victims, was constantly under attack, often by his own political compatriots. The terms they used to denounce the Jewish state — Israel was excoriated as a ruthless aggressor and oppressor, denounced as an overly militarised state guilty of acts of fascist violence, condemned as a brutish colonialist power, a bridgehead of American imperialism in the Middle East, an agent of capitalist conspiracies, and so on — all these denunciations were right out of the Marxist playbook. A long-standing member of the left himself, Améry was familiar with the ideological origin and formulaic nature of these terms and was convinced that their application to Israel was unfair and grossly off the mark. Moreover, he saw them as dangerous, for the steady defamation of Israel as a criminal state had the effect of demonising the country and preparing the ground for its elimination. Nothing provoked Améry more than that nightmarish possibility. More than anything else in his last years, it spurred him on to raise his voice as a ‘vehemently protesting Jew’ in defense of Israel.

Although written almost half a century ago, his essays could not be more timely, for they speak to problems that not only troubled Améry in the 1960s and 1970s but have intensified in more recent years. Especially under the camouflage term of anti-Zionism, animosity to Jews and, especially, the Jewish state has escalated over the last two decades and on a global scale. Such hatred has also become more lethal. Jews have been attacked and sometimes killed in Berlin, Burgas, Brussels, Caracas, Copenhagen, Malmo, Mumbai, Paris, Toulouse, and elsewhere, including in American cities. A number of these assaults, carried out by people acting on behalf of Palestinian or Islamist organisations, are examples of Middle Eastern terrorism exported to other parts of the world for ideological and political purposes. Some attacks have been the work of lone actors seemingly bent on doing harm to Jews for other reasons, some of them economic, some quasi-religious, and still others simply inexplicable.

In recent years, and to the surprise of many, the US has also witnessed the spread of aggressive antisemitic passions, as was graphically illustrated on 12 August 2017, at the infamous Unite the Right rally of white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and Klansmen in Charlottesville, Virginia. The slogans that accompanied this march — ’End Jewish influence in America,’ ‘Jews will not replace us,’ ‘Jews are the children of Satan’ — dismayed onlookers, who were unaccustomed to seeing such raw antisemitism displayed on the streets of American cities. Even worse, the mass shooting of people at prayer in a Pittsburgh synagogue, on October 27, 2018, followed 6 months later by a lethal attack on a Chabad synagogue in Poway California, drove home the realisation that the US, too, was not immune to acts of violent Jew-hatred. Its history has never been free of social biases against Jews and episodes of antisemitic violence, but compared to the situation of Jews in European and Middle Eastern countries, Jews in the US have lived a relatively safe and normal life, especially in recent decades. Charlottesville, Pittsburgh, Poway, and other brutal antisemitic assaults, however, have set American Jewish nerves on edge. A new sense of unease is now palpable in American Jewish communities.

The major perpetrators of the most destructive acts against Jews and Jewish institutions in Europe, South America, and the Middle East in recent years have been radicalised Muslims, although in some cases antisemitic acts have also been carried out by neo-Nazis, extreme populists and nationalists, and assorted street thugs. In the US, the most potent antisemitic threat at the physical level right now is found chiefly among white nationalists, white supremacists, neo-Nazis and others on the far right, militant Muslims, and antagonistic African-Americans. While some of these types existed in the Europe of Améry’s day, they were, for the most part, less active in carrying out assaults against Jews than some of them have since become.

Writing in the 1960s and 1970s, Améry’s deepest concern was not so much with the neo-Nazi right as with his fellow partisans on the left, whose ideological anti-Israel hostility, in combination with the irrational hatreds of Europe’s traditional attitudes toward Jews, he saw as the most dangerous form of contemporary antisemitism. Their goals were clear to him. To the antisemites, the Jew must always be eliminated, he firmly believed. To the anti-Zionists, the Jewish state must be eliminated. And ‘leftists are now the most eloquent proponents of anti-Zionism in all its brutishness.’

‘How,’ he wondered, ‘did Marxist dialectical thought come to lend itself to the preparation of the coming genocide?’ This last phrase stuns by the magnitude of the disaster that Améry saw in the offing. Was it an exaggeration to think about the future in these alarming terms? Not in Améry’s view, for unless the fervor that fueled anti-Zionist antisemitism could be effectively checked among his former allies on the left, he was convinced they were bound on a destructive course. By focusing their militant and obsessive anti-Jewish ‘hallucinations’ on the state of Israel, they were bent on singling out Jews once again for a calamity of historical proportions. He called it ‘Auschwitz on the Mediterranean.’ Determined to raise his voice against such a nightmarish prospect, Améry devoted some of the sharpest and most incisive of his analytical and polemical writings in his last years to opposing anti-Zionism, most especially as it sought to advance its goals in progressive circles under the banners of human rights, antiracism, and universal justice. A cosmopolitan thinker, Améry placed a high value on all these principles and defended them repeatedly in his writings, but not when they were being cynically exploited for political ends that he saw as noxious. In his own words: ‘Antisemitism in the guise of anti-Zionism has come to be seen as a virtue.’ Améry saw such a claim as bogus and malign, and he waged a determined battle against it in his late writings.

To anyone aware of the return of antisemitism in our own day, the pertinence of Améry’s arguments will be obvious. A newly energised and increasingly pervasive hostility to Jews and the Jewish state has become a prominent and pernicious feature of contemporary social life and political opinion. It shows up in physical assaults on Jews and Jewish synagogues, schools, community centers, cemeteries, museums, and Holocaust memorials. These attacks, some of them resulting in fatalities, now number in the hundreds in countries across the globe. In addition, and in some of its most impassioned forms, today’s anti-Jewish animus focuses relentlessly on the state of Israel, sometimes going so far as to brand it a criminal entity akin to apartheid South Africa and Nazi Germany. Such anti-Israel passions find especially sharp political expression on numerous university campuses, where students are now regularly exposed to forms of hostility that range from the shouting down of Israeli speakers; to aggressive boycott, divest, and sanction campaigns; to annual springtime hate-fests called Israel Apartheid Week. The ritualisation of these anti-Israel activities has been going on for years on some campuses and has the effect of making anti-Zionism a ‘normal’ part of the college experience for numbers of students. Faculty members in certain academic disciplines are also actively involved in the boycott movement, sometimes urging their universities to break collegial ties with Israeli universities and discouraging their students from doing study-abroad programmes in Israel.

The aim of these anti-Israel activities at their most extreme is to demonise and delegitimise the Jewish state in ways that recall the marginalisation and dehumanisation of Jews in Nazi Germany. The propaganda effect of such defamation worked against the Jews during the Third Reich, and Améry believed that it could work once again, this time against the Jewish state and its supporters. And so he raised his voice tirelessly against both antisemitism and anti-Zionism and the growing links he observed between the two.

He was not alone in doing so. Closer to our own day, Per Ahlmark, a former deputy prime minister of Sweden, wrote that ‘anti-Semites of different centuries had always aimed at destroying the then center of Jewish existence … Today, when the Jewish state has become a center of Jewish identity and a source of pride and protection for most Jews, Zionism is being slandered as a racist ideology.’ The aim of such slander is to reduce the state that Zionism founded to an entity unworthy of retaining a place within the family of civilised nations. More recently, other world leaders have also spoken out strongly against such bigotry, noting that anti-Zionism is nothing other than a reinvention of antisemitism. In October 2015, for instance, Pope Francis was emphatic in pronouncing against it: ‘To attack Jews is antisemitism, but an outright attack on the state of Israel is also antisemitism.’

Améry wrote similarly about the threats that a revived antisemitism, often under the cover of anti-Zionism, would pose, and not only to Jews but also to post-war Western civilisation at large. Reflecting on developments since his first book appeared, he noted, ‘When I set about writing, and finished, there was no antisemitism in Germany, or more correctly: where it did exist, it did not dare to show itself.’ As he looked about him, he recognised that those days were gone, and not only in Germany. Antisemitism was no longer hidden covertly in the shadows but was, once again, a threatening presence in the public sphere. If its most aggressive adherents were to gain still more prominence, the result, he was sure, would be a reinvigoration of eliminationist passions that could bring on new disasters. In his most severe vision of what such a turn might produce, he referred, chillingly, to ‘Auschwitz II.’

It is a fearsome prospect and, one hopes, it will never come about. Meanwhile, Améry’s writings, the product of its author’s painfully intimate knowledge of Auschwitz, stand before us in all their argumentative urgency as admonition and warning. We would do well to take them seriously.[1]

References

[1] See Jean Améry, At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities, translated by Sidney Rosenfeld and Stella P. Rosenfeld (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1980) and Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left, edited by Marlene Gallner, translated by Lars Fischer (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, forthcoming). All quotations in this essay are taken from these two books.

I find it hard not to see a strong correlation between the increasing levels of anti-Zionist activism in the West and the ever-increasing size of the Muslim population in the West.