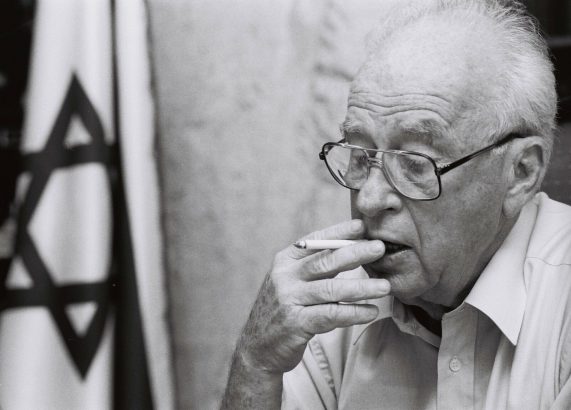

Gidi Grinstein, who served as secretary of the Israeli delegation for the Camp David negotiations, argues that the embattled Oslo Accords will eventually emerge as the only possible cornerstone for the regulation of Gaza in the post-war era. This article is also related to a piece Grinstein wrote about international recognition of a Palestinian state which can be found here.

Recent weeks have proven that the war in Gaza will continue for much longer than initially expected in the aftermath of 10/7. With no ceasefire-hostage deal in sight, it seems as if an “unbreakable” Hamas and a defiant Israeli government lock horns in an endless military confrontation. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Netanyahu insists that Israel remains in the Philadelphi Corridor and controls the perimeter of Gaza, as well as rejects any role for the Palestinian Authority (PA) in Gaza even when Hamas is demolished and removed.

In this context, any discussion of the “day after” the Israel-Hamas war and the longer-term “political horizon” of Gaza seems futile. Nonetheless, many organisations and individuals – in Israel, among Palestinians, across the Middle East, in the US, and in Europe – have already begun to plan and prepare ahead. Yet all their proposals contain giant loopholes because they fail to be explicit about the legal framework that will govern Gaza in the aftermath of the war.

This article argues that the embattled Oslo Accords will eventually emerge as the only possible cornerstone for the regulation of Gaza in the post-war era. The reinstitution of the Oslo Accords over Gaza for a new “interim period” of a few years will allow for the formation of an international force that will undertake Gaza’s reconstruction. It will also create a window for the upgrade and reform of the PA, as well as for proper transition of its leadership, as president Mahmoud Abbas enters his 90th year. In particular, the re-division of Gaza into Area A and Area B, with no Area C, can address Israel’s security demands, while assuring the Palestinian side and the Arab world that all of Gaza will be Palestinian in permanent status. And there are additional collateral benefits as well.

The Arab Framework for an International Force

All ideas regarding the “day after” the Israel-Hamas war have suggested some combination of an international force or trusteeship that will include “kosherised” Palestinian forces. The goals of such a force are monumental: to reestablish security in Gaza and fight terrorist insurgencies, as well as to function as an effective government that does post-war clean-up, rehabilitation, reconstruction and de-radicalisation. In addition, it seems that Israel and the US call for the international force to be led by, composed of, and financed by Arab countries such as the UAE, Egypt and Saudi Arabia in collaboration with the US and other western nations. Some even mention a contingency of NATO forces. These generalisations capture most of the agreement, however limited, with regards to the possibility of an international force, while all other aspects – such as its size, composition and mandate – remain “to be determined.”

At the same time, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan have repeatedly established that they will only contribute to such an international force if it is “invited” by legitimate Palestinian institutions, namely the PLO or PA, to avoid being seen as an “occupying force” in Gaza. They also demand that the international force must be introduced in the context of a “political horizon” that includes “an irreversible path to Palestinian statehood.”

Netanyahu’s Non-Negotiable Demands

Yet these expectations clash with Netanyahu’s positions, which reject even a reference to the possibility of a Palestinian state in Gaza’s political horizon and deny any role for the PA in Gaza even when Hamas is removed. And there are additional Israeli demands as well: UNRWA, which is the second largest service-providing agency in Gaza and the West Bank, must be withdrawn or dismantled, which would exacerbate disorder just when stability will be essential; Israel needs to control the perimeter of Gaza, which is anticipated to be 1-1.5 km wide, covering 80 square kilometers or nearly 25 percent of Gaza’s territory; and the IDF will have the freedom to operate within all areas of Gaza, even where the international force is deployed.

In other words, Netanyahu’s “vision” calls for a non-PA-non-Fatah-non-Hamas Palestinian governing body that is accepted and supported by local clans and paid for by “Arab countries.” That Gazan self-governing body will invite the international force to deploy in Gaza and replace UNRWA without any political horizon of independence. Those arrangements will be limited to the areas that are within the perimeter, which will remain under Israel’s control, while the IDF has freedom to operate in the entire area of Gaza at its will. Good luck with that…

The paradoxes and internal contradictions in Netanyahu’s positions are glaring and unsustainable. While Netanyahu pledged that Israel will not annex any part of Gaza or resettle Israelis there, he also committed that Israel will control Gaza’s perimeter indefinitely, which means that Israel will have “effective control of Gaza” and will therefore have to undertake the burden of its government. Netanyahu also envisions a Palestinian governing body in Gaza that emerges without any official agreement between Israel and a Palestinian representative body. Hence, while these governing arrangements are interim and provisional by their nature, they are also supposed to be “indefinite.” Furthermore, “deradicalisation” is to be achieved when Gazans have no prospect of self-determination within a Palestinian state even in the theoretical scenario of full compliance with all of Israel’s security and other demands.

No Zone of Possible Agreement

Netanyahu’s positions destine any negotiations regarding the future of Gaza to an impasse. Nonetheless, backchannel discussions between Israeli ministers and officials and key regional stakeholders regarding the “day after” are already taking place. As expected, they reveal that there is no “zone of possible agreement” between the sides. And even if such an agreement would miraculously emerge on the level of principles through wordsmithing among diplomats and lawyers, an additional set of must-answer questions will immediately surface to prevent any additional progress.

Take for example the issue of movement of goods among Gaza, Israel, Egypt and the world, namely imports to and exports from Gaza: Who will inspect overseas shipments: Israel, Egypt, the international force in Gaza or the PA? Who will determine which goods are taxable or exempt and the amount of taxes that will be collected? What standards will apply to goods entering Gaza: Israel’s first-world standards, Egyptian or Palestinian? Most importantly, who will receive the tax revenues and be responsible for their allocation? If resolving the issue of Gaza’s imports and exports sounds complicated, well, it is just one example out of dozens of similarly complex matters.

Hence, a newly created mandate for an international force is nearly impossible to formulate. As a reference point, hundreds of Israeli and Palestinian experts in multiple working groups negotiated for nearly a year to create the Interim Agreement (known as “Oslo B”), which has governed the relations between Israel and the PA since September 1995. Furthermore, the successful conclusion of that 1995 Interim Agreement was made possible by an agreed and robust political framework, which included the 1993 Declaration of Principles (known as “Oslo A”) that outlined a political process toward resolving the core issues of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; the 1994 Gaza-Jericho Agreement that provided for the establishment of the PA; and the 1994 Paris Protocol that regulated economic and trade relations. Alas, that overarching political framework is currently lacking regarding post-war Gaza, which is why finalising a mandate for an international force is mission impossible.

How about going back to the Oslo Accords?

There is, however, an alternative course of action, which involves reinvigorating the embattled Oslo Accords and the logic of the Oslo Process. According to these agreements, an Interim Period of five years, from May 1994 to May 1999, was intended to lead to the “permanent status” of Israeli-Palestinian relations likely based on the principle of two nation states for two peoples. From 1993 to 1999, some eleven agreements were signed between Israel and the PLO, which are still officially in force, never revoked by either party.

Unfortunately, many currently believe that the Oslo Process is “dead” or no-longer relevant. This is understandable following 17 years of Hamas rule of Gaza, and 10 years of an Israeli government policy, which worked to divide the PA and the Palestinian national movement between Hamas-controlled Gaza and the PA in the West Bank. During this period, Abbas could not credibly claim to represent all Palestinian territories or people, and Netanyahu easily brushed off any pressure to negotiate a permanent status deal, which would have threatened his governing coalitions. Recently, perhaps since 2014, even proponents of the “two-state solution,” including US administrations, rarely mention the Oslo Accords as a reference point for the parties’ past or current obligations, or for future mutual expectations.

But the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza represents a potential sea change in the condition of Israeli-Palestinian relations in at least two fundamental ways: Hamas will no longer control Gaza and Israel effectively canceled its 2005 “disengagement from Gaza” by reestablishing military presence within Gaza and by setting demands for Gaza’s future.

Three scenarios but only one is realistic

Ahead of some form of a ceasefire – which may be months or years away – there are three basic scenarios for the future of Gaza: the first is that Israel will eventually assume direct civil and military control over Gaza’s territory and population. The second, which is demanded by Netanyahu, is for Gaza to be bifurcated from the PA in the West Bank and subjected to a non-Hamas-non-Fatah Palestinian self-governing body that has the support of an international force, while Israel’s security requirements are addressed. The third scenario is the reunification of Gaza and the Palestinian areas in the West Bank within a single territorial and political framework, which is led by a “reformed” and “upgraded” PA for an initial interim period of a few years until the permanent status of Gaza and the West Bank can be determined.

The first two scenarios are unsustainable. If Israel controls post-war Gaza, it will do so alone and eventually face an unbearable economic, military, and diplomatic burden, which will then push it to explore how to exit Gaza. The second scenario is unlikely because no one agrees to Netanyahu’s conditions. Therefore, all parties are likely to converge around the third scenario of reintegration of Gaza and the West Bank within one political framework, even if each area is governed by a separate local government.

Ambiguous political horizon

There are many advantages for reinstituting the Oslo Accords in Gaza for another interim period. First, these accords are ambiguous about Permanent Status, which, in this case, is a positive due to the depth of the current crisis, the unprecedented levels of hostility and trauma, and the gap in the parties’ positions. The 1993 Declaration of Principles mentions a list of “outstanding issues” such as borders and territory, Jerusalem, refugees, and settlements, that should have been resolved through negotiations and agreement by the end of the “original” Interim Period, namely by May 1999. Clearly, since Israel and the PLO have not reached an agreement on Permanent Status, the 1993 Declaration of Principles could be used again as a basis for launching a new interim period after the war in Gaza.

In addition, the Oslo Accords are based on United Nations Security Council Resolution 242. Its French version is understood to call for Israeli withdrawal from all the territories that were taken over in 1967, as per the Palestinian demand. Meanwhile, the English version of 242, upheld by Israel since 1978, calls for Israeli withdrawal “from territories,” thereby opening the door for a territorial compromise within the West Bank and Gaza. Yet again, that ambiguity could well-serve those who design the next phase of Israeli-Palestinian relations.

In the Oslo Accords and consistent with the logic of 242, Israel and the PLO agreed that the West Bank and the Gaza Strip would be divided into three types of areas: “Area A” which is fully controlled by the PA in terms of security and civil affairs and currently covers ~18 percent of the West Bank; “Area B” which is under Israeli security control and Palestinian civil control, covering an additional 22 percent of the West Bank; and “Area C,” which covers the remainder of the West Bank and includes settlements, military installations, main roads and even areas that control the underground water aquifer.

According to the Oslo Accords, Area C is under full Israeli control and its fate will be determined in the Permanent Status agreement. In other words, the accords implicitly designated all of Area A and Area B as part of the “Palestinian entity” in permanent status. That principle guided all peace negotiations since 1999, as well as the Trump Plan, which was published in 2020, and may be crucial for designing Gaza’s future.

A similar categorisation of areas existed in Gaza prior to Israel’s disengagement from the Gaza Strip in 2005. In fact, when Israel withdrew Gaza in 2005, it effectively handed over Gaza’s Area C to the PA, including 17 settlements and the Philadelphi Corridor. Namely, that withdrawal effectively turned all of Gaza into Area A, and henceforth Israel maintained no territorial claims to Gaza, treating its area as foreign territory, which is governed by the PA according to the Oslo Accords. In June 2007, Hamas took over Gaza and immediately declared the Oslo Accords null and void. Since then, the demand to re-apply the Oslo Accords to Gaza has remained a major sticking point between Abbas and Hamas.

The legal reality in Gaza is going to change once Hamas is no longer in power. At that point, Oslo’s territorial arrangements, which currently exist in the West Bank, can be re-introduced to Gaza: the areas which the Palestinian entity controls in Gaza will be defined as “Area A,” while the security perimeter, which Israel demands, including the Philadelphi Corridor, can be defined as “Area B,” as long as such arrangements are consistent with the peace treaty with Egypt. Meanwhile, no part of Gaza should be declared as “Area C” and no Israeli settlements should be built in Gaza.

Such re-application of the Oslo Accords to Gaza addresses Israel’s core security demands, while ensuring that the entire Gaza Strip will ultimately be Palestinian in its permanent status, even if the issue of Palestinian statehood is not explicated at this point. In addition, such an arrangement will reintroduce an entire body of agreed technical arrangements – most importantly the Paris Protocol on economic affairs; the security protocol that also regulates Israeli “hot pursuits” of terrorists; and the operation of the donor community – all of which can allow for an immediate introduction of the international force.

Creating an Interim Period between the ‘Day After’ and a Political Horizon

Designating another “interim period” means that detailed discussions of the core issues of permanent Status between Israel and the PLO will be deferred for a few years. In the meantime, a lot of other work should take place. First, the Oslo Accords provide a necessary context for the much-needed reform of the PA, as has been advocated by the UAE and other countries, as well as for an orderly succession of the presidency of the PA from Abbas to his successor. Second, the monumental task of Gaza’s reconstruction can take place, allowing for a gradual withdrawal of UNRWA from Gaza, when families of “refugee status” receive new permanent homes and the areas of the “refugee camps” are rebuilt as permanent modern neighborhoods. Finally, in the absence of any Israeli territorial claim to Gaza and with an implied political horizon of statehood, the work of deradicalisation can legitimately unfold.

While the reinvigorating of the Oslo Accords may seem a fantastical idea, it is also the only viable option for a political path out of the war and toward a political horizon, which is justified by the elimination of all other options and because of its benefits for all parties. And if this is indeed the most likely scenario for post-war Gaza, then all parties who uphold it should begin their preparations now.