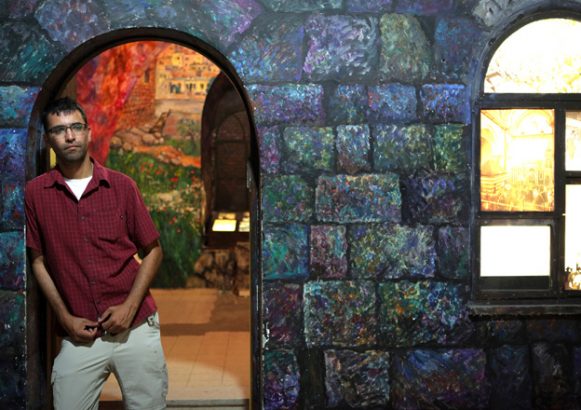

Aziz Abu Sarah is a National Geographic Explorer and Cultural Educator. A Palestinian from Jerusalem, Aziz has pioneered and managed many projects in conflict resolution and community relations. He spoke to Fathom editor Alan Johnson.

Alan Johnson: Can you tell us a little about yourself and your journey?

Aziz Abu Sarah: I grew up in Jerusalem in a very conservative Muslim family, and my introduction to the conflict was when my mum gave me an onion to take to school because of the tear gas. My brother was killed when I was 10 years old. He was 18. He was arrested on suspicion of throwing stones and was forced into a confession by being beaten, which resulted in internal injuries that eventually caused his death a year later. So I grew up angry and revengeful, wanting to make the other side pay for what they did to my brother. I was like that for 8 years.

When I was 18 I went to study Hebrew. Even though it was mandatory in my high school, I hadn’t learnt it. I decided I was not going to learn the language of the enemy. Then I realised, ‘I’m in Jerusalem, so if I don’t speak Hebrew, I am not going to advance in life.’ I was the only Palestinian in the Hebrew class.

AJ: What was the class like for you?

AAS: The class was scary and uncomfortable at first. All my interactions with Israeli-Jews to that point had been negative. I could not have a normal relation with the settlers who would attack our neighbourhoods, and we’d throw rocks at them. So when I found myself sitting in a classroom where everybody is Jewish, I’m thinking to myself, ‘they’re going to beat the crap out of me!’ I didn’t want to talk to anybody and my brain was racing with all these ideas – fear, ignorance and anger. I didn’t know what to do with myself.

But the students were the most amazing people. I was blessed. My teacher went out of her way to make me feel comfortable. She would bring things from the Palestinian community to class as teaching aides. She recognised my culture, she recognised who I was, and she even played an Arabic song in class and asked me to translate it with her for the class. I felt for the first time that there was an Israeli who listened to me, who cared about me, who really saw me as a human being.

As a group we would go out to drink coffee together. We didn’t have enough Hebrew to get into political discussions, so we would talk about things that 18 years olds talk about. Eventually we started talking about politics. Sometimes we would agree and sometimes we would disagree, but our friendship made a difference. The next time there was a suicide bomber, I didn’t say to myself, ‘well, it happened to them and they’re my enemy.’ I said to myself ‘wait, this is very close to where my friend lives.’ So I picked up the phone and called to make sure they were fine. And the next time there was a shooting, a Palestinian was killed, or settlers attacked my neighbourhood, my Israeli friends started calling me to make sure that I was fine.

That shifted the whole dynamic. From that point my life changed completely. I started to realise that I didn’t know anything about anybody other than about my own people. Most Israelis probably have the same experience.

What we really need to do is build bridges between these two communities, especially among young people, and this has become my work. At the beginning I joined an organisation called Bereaved Families Forum. I was the chairman for a few years and we did a lot of work bringing Israelis into Palestinian classrooms in East Jerusalem, which was very challenging.

I then created a radio show; the only one that broadcast in both Arabic and Hebrew. I was a translator and we focused on storytelling. We asked people to tell our listeners stories of how they worked together across the divide. I hosted it with a Jewish friend of mine who was also from a bereaved family. Although it only lasted a few years, it was an amazing experience. Eventually I expanded my experiences, working in Afghanistan, Turkey, Syria and Iran, and in many other countries.

AJ: You quote from Proverbs to sum up what you see as the greatest challenge facing Israel. ‘Where there is no vision, the people perish.’ Why that quote in particular?

AAS: The occupation is a big deal; internal issues in Israel are a big deal; the whole radicalisation of communities is a big deal; and terrorist attacks are a big deal. But you can deal with every challenge you face if you have a vision and hope. Proverbs also says: ‘Where there is no vision, there is no hope.’ I don’t believe that the Israeli government of today has a vision for what to do with the Palestinians, with the conflict, or with internal issues in Israel. When a member of the Knesset says, ‘I think we should make Arabic not a formal language’ and then another counters, ‘I think we should take the Palestinian members of the Knesset out if they say something we disagree with’, it’s not coming out of a strategy. It’s coming out of not knowing what to do and wanting to please their voters, instead of having an idea of what kind of community they want Israel to be.

Different members of the Israeli government have totally different visions. Some talk of a one-state solution, some of a two-state solution, whilst others talk of ‘conflict management’, not conflict resolution. There is no real idea of where they want to go and how it’s going to end.

When you ask Israeli people what they think is going to happen they say ‘well, we want peace, but we don’t think it’s going to happen.’ The reason for that is because they don’t see anybody giving them a vision so they have no hope. There is no leadership. Bibi Netanyahu says ‘we shall live by the sword’ but that’s not a vision.

AJ: I asked a Palestinian academic at Exeter University about the trends of opinion in Palestinian society. She said there are not really coherent trends of opinion, as such, only alienation, frustration, and hopelessness. She thinks things could go in any direction. Do you think her reading is accurate?

AAS: There is a continuous frustration on the Palestinian side. I explain to my Israeli friends that when a Palestinian says he doesn’t believe in a two-state solution, that does not mean ‘I want to destroy Israel.’ It means they have lost hope. They see the settlements grow and the Palestinian Authority is completely disabled; they are marginalized and they don’t have any democratic rights anymore – even in the Palestinian territories, there are no elections, no freedom, and you can’t move between one Palestinian city to another.

The Palestinian authorities don’t know what to do. I think President Abbas is hoping that either the international community is going to make change happen, or Israel will suddenly realise that they should give the Palestinians their freedom. Abbas is not actively doing anything to make a difference.

If you ask any Palestinian about the future, they’ll tell you: ‘I have no idea where we’re going. I have no idea what the plan is. Why should I even go to protest? What will it lead to?’ Where is the political goal?’ The first intifada had a political goal and it forced Israel to recognise the Palestinians and negotiate with them and that led to the Oslo Agreement and we felt we were on track for a Palestinian state. Today, if you go out to protest, you are not sure what impact you have, because there is no vision. Partly that is because our leader is 81 years old and he is trying to leave a legacy, but in truth, he’s not committed to lead. It’s a very troubling situation. We don’t know who is going to be the next leader, and the struggle will be a big one within the Palestinian Authority.

AJ: Some Israelis are worried about the possibility of a very messy succession. How you think Palestinian society, and the Palestinian National Movement in particular, will react to the succession question when it is posed?

AAS: We need to hold elections as soon as possible. President Abbas should not die in office. I think that would be a disaster. We don’t have a vice president who would take over. Instead, politicians will vie. The only responsible way to avoid that situation is for President Abbas to set up new elections where those people can compete at the ballot box. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, it is not happening. The fear is that Hamas might win the presidency. I think that is unlikely, especially if people have hope in the Palestinian Authority. But that is where Israel comes back into the picture, of course.

AJ: Today’s conference was about security. You spoke of ‘threats that are often not real threats.’ But isn’t there a lot for sober people to be very frightened of, from Hezbollah’s rockets to the Iranian threat to ISIS and jihadism?

AAS: I didn’t mean to say that those threats are not real. I meant to say that these threats are not the main ones. A few months ago, Israel’s IDF Chief said: ‘Iran is not our main threat, it’s not our big issue, and we’re not worried about it’. And when you hear the Prime Minister saying in the same week that ‘Iran is the biggest existential threat to Israel’, it makes you wonder, why the difference? Is ISIS a problem? Absolutely. Is Hezbollah a problem? Yes. But Israel is way more powerful than either of those. Those groups are not an existential threat to Israel. In reality, it is by dealing with the issues of occupation – the Palestinians, Gaza etc. – Israel would be weakening those groups. You would weaken Hezbollah, ISIS and Iran, because they all use the Palestinians. Everybody likes to talk about the Palestinians. By dealing with the Palestinian issue, you don’t solve every problem, but you do weaken these groups significantly.

AJ: Can Israel’s Palestinian citizens play the role of a bridge between the two peoples? What are the obstacles to them playing that role?

AAS: Let me say, as a citizen of Jerusalem, I get some of the benefits Israeli citizens get and I don’t get some others. I cannot vote in Israeli elections but I do have healthcare. So my relationship with Israel is unique. I learnt to appreciate the things I see in Israel – especially after going to America and seeing the healthcare system. It’s important for the Palestinian citizens of Israel to be able to see the positive and the negative of Israel. That’s where Israeli Palestinians have this dual struggle because, on the one hand, they are citizens of Israel – they go to university in Israel and they want to get jobs in Israel – but, on the other hand, they don’t have the same opportunities. And when you don’t have the same opportunities, it limits who you are. You’re not included, your national symbols are not part of the country, and your history and culture is not recognised by your own state. And if you are pushed aside like this, then eventually you are going to rebel. It’s very hard to be a bridge to an Israeli side that is not accepting you in many ways, that thinks your relationship with the Palestinians in the West Bank is an act of treason, not a bridge.

If they are to be the bridge between the two sides, then they have to take their full place in the Israeli community: more equality, the removal of laws which discriminate against them. And they should be allowed to build more relationships with their Palestinian brothers in the West Bank and in Gaza.

AJ: I don’t know if you saw the profile of Ayman Odeh in The New Yorker by David Remnick? Remnick met Odeh in the Knesset cafeteria and some politicians come over and talked to Remnick about Odeh, as if Odeh was not sitting there. Remnick was shocked. Odeh says, ‘This is what it’s like.’ What do you think about Odeh as a leader?

AAS: He’s in a very difficult job and I think he’s doing the best he can. He’s an interesting guy because on the one hand he is very principled, very clear on his stand on the Palestinian issue, and he’s also working very hard at advancing equality for Palestinians who are citizens of Israel. He is also reaching out to the Jewish community, saying his party is not only a party for Arabs, but it should also defend the rights of Jewish citizens who are marginalised in Israel.

AJ: You say ‘We need to stop telling ourselves we’re victims of each other, and we need to think of ourselves as survivors.’ Why?

AAS: You turn into a survivor instead of a victim when you put your narrative into something grander, something beautiful: ‘I suffer, but there’s a greater cause. There’s something more important than my suffering, I’m part of a bigger world.’ I worked a lot with Syrian refugees. Those who saw themselves as victims were the most miserable refugees; their trauma got worse and worse because they were re-living their trauma every day. The chance of them being radicalised was higher. Those living in the same situation – in the same refugee camps – who told a different story about themselves, who said ‘We have suffered but we’re not giving up, we have a chance to make things happen’ fared better. These are two very different mind sets, depending on how the trauma has been processed.

So the question becomes, ‘How do we change the discourse?’ A project I’m working on is called ‘I’m Your Protector’. I work with a Jewish friend from New York. The idea is that we need to start bringing out different kinds of stories and narratives. Netanyahu talks about how the Mufti supported Nazis. True, he did. But that’s not the only story about Muslims during the Holocaust. How about the stories of the many Muslim people who rescued Jews? We started going through these stories one by one, publishing them, and putting them on billboards. For example, about the Mosque Imam in Paris who would forge letters for Jews, claiming that they were Muslims. Why don’t we talk about that story?

You can always find a story that can reinforce a narrative of besiegement and victimhood. Or you can look for the kind of stories I just mentioned. We need to use those stories to change people’s thinking.

AJ: What kind of activism in the West do you think is constructive?

AAS: First, don’t be active from a place of hatred. Say instead, ‘I want to make a difference.’ You can be critical, but if you’re coming from a place of hatred your work will eventually be destructive, regardless of whether you’re pro-Israel or pro-Palestine. You know, sometimes I’ll tell people I’m Palestinian and they’ll start saying horrible things about Jews. They assume that if I’m Palestinian I must hate all Jews. So we all have to be careful.

Second, I believe a lot in storytelling. When you are stuck and you don’t know what to do, tell stories and educate with these stories. Facts and numbers are important, but we are creatures that are moved by emotions – even the British, probably! So people should learn how to tell their story: Why do you care about this issue? What moved you about this issue? And if there are more and more people telling their stories and educating others, then the whole ‘pro-Israel, pro-Palestine’ narrative will change. Maybe it will become: ‘How do we find the solution?’ Not ‘I do this because I’m pro-Palestine’, but, ‘I do this because I’m pro-justice.’

Third, get involved in policy work and write to your Member of Parliament. If you disagree with donations going to settlements, for example, government policy does not change unless you start pushing governments. At the same time, I think most of the investment into policy work should be positive. If you are going to boycott something because you think it is bad, I would say you also have to invest. Invest in a Palestinian or a joint venture; invest in the organisations, the people, the businesses that are positive.

Boycott is easy, investment is hard. When you start doing that it sends a positive message instead of a negative one. You are saying, ‘I want to help’, not just ‘I want to destroy.’ So that is a big priority and I know some of my Palestinian friends might disagree with me, but I believe in collaboration. I wouldn’t buy anything from a settlement, but I tell people to not only boycott settlement goods but to put your money into what you say you really care about. If you care about the Palestinian community, then fine. If you care about Arabs and Jews working together, invest in that.

Comments are closed.