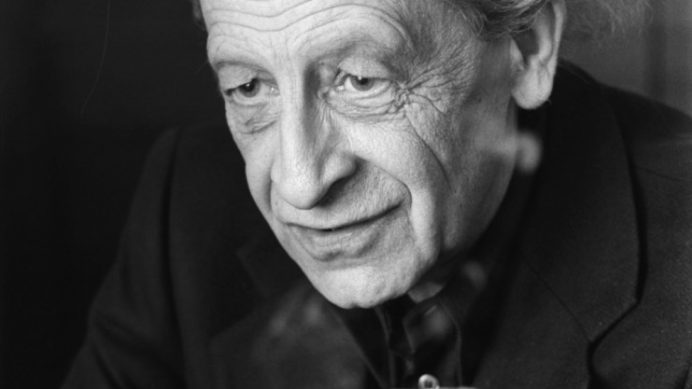

Marlene Gallner explores the thoughts of Jean Améry about the Dilemma for Left-Wing Jewish Intellectuals, Sartre’s notion of ‘Freedom of Choice’ and Commitment towards Israel.

The writer and Holocaust survivor Jean Améry was among the first to criticise anti-Zionism as the new and popular face of antisemitism. Between 1966 and 1978, he published several essays on the topic in various German-language newspapers and magazines. One, however, was deliberately ignored time and time again. It was not included in the related volume of Améry’s collected writings, published posthumously in the 2000s, and left out again in a 2024 book the German publisher brought out in response to 7 October.[1] It seems that the text is inconvenient. Reading it, it is difficult to come to the conclusion with which the 2024 book is marketed, namely that Améry’s solidarity with Israel as a leftist was not unconditional. The essay in question is ‘Between Vietnam and Israel. The Dilemma of Political Commitment.’ The text treats an issue that could not be more relevant today: the dilemma left-wing Jewish intellectuals face between being left-wing and being Jewish and why the commitment to Israel is not a political position one can assume or abandon.

Vietnam and Israel

Améry wrote ‘Between Vietnam and Israel’ shortly before the Six-Day War. The essay actually appeared during the war, on 9 June 1967, in the Swiss magazine Die Weltwoche. It is the second Améry text – after ‘On the Impossible Obligation to Be a Jew,’ which had aired as a radio essay in West Germany the year prior – in which he specifically addresses questions of antisemitism, being a Jew, and the role of Israel. After finishing the studio recording of ‘On the Impossible Obligation to Be a Jew,’ Améry stated in a letter to his editor that he had ‘had enough of this topic for the next half century!’[2] But the subject matter caught up with him again, whether he wanted it to or not.

In May 1967, a few months after Améry sent in his letter, the armies of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria advanced to the border with Israel. Tens of thousands of soldiers from Iraq, Kuwait, Algeria, and Saudi Arabia also stood ready for the planned attack. The Soviet Union sent military advisors and war equipment. Their common goal was nothing less than wiping the only Jewish state off the map, as announced by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser on 27 May 1967: ‘Our basic objective will be the destruction of Israel. The Arab people want to fight.’[3]

Améry recognised in this fervour the same death threat that he had personally witnessed and saw enacted in the Nazi extermination camps. ‘The Arab states, supported by the Soviet Union and the entire socialist bloc, seemed to be on the verge of snuffing out the tiny state of Israel,’[4] he agonised. His realisation ‘that being a Jew meant being a dead man on furlough, somebody who was to be murdered, who by mere coincidence was not yet where he ought, by rights, to be,’[5] directly affected the Jewish state for the first time since its War of Independence in 1948. The author’s yearning to no longer have to speak of antisemitism remained merely a noble wish.

At the same time, the USA was waging a devastating war alongside South Vietnam against the socialist North Vietnam in order to curb the growing influence of the Soviet Union in Asia. How sensible the US intervention in the Vietnam War was was increasingly questioned in America and Europe. Almost 60,000 American soldiers fell and, according to various sources, a total of 400,000 to 600,000 Vietnamese civilians were killed. For left-wing intellectuals, it was obvious that they needed to take a stand against US interference in the conflict. Améry, who saw himself politically as a leftist since his early adulthood, also expressed himself unequivocally: ‘… America absolutely is pursuing a policy of belligerent violence in Vietnam …’[6]

Also in the same year, as Améry mentions in his essay, an extreme right-wing military dictatorship seized power in Greece. A brutal military junta ruled Bolivia. And a year earlier, in 1966, the writers Yuli Markovich Daniel and Andrei Donatovich Sinyavsky were sentenced in the Soviet Union in a sensational show trial for ‘anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.’ Internationally, their case caused great consternation. In short: in several cases, left-wing intellectual commitment – as Améry defined it, the physical commitment to what one speaks and writes – would be called for.

Freedom of Choice in the Face of Antisemitism

Before the Arab armies gathered to annihilate Israel, Améry still took the view that one should always adopt a clearly left-wing position when it comes to the question of political practice. He did not seem averse to defending ‘the commitment to a cause, which might not be a genuine good cause yet but would, as opposed to others, seem to have the potential of one day becoming one.’[7] As a left-wing intellectual and a Jew, however, he faced a crucial dilemma, which was why he could not freely decide on his commitment. Although the Vietnam War had the potential to escalate into a third world war at the time, for Améry, as for all Jews worldwide, the war over Israel was the existential one.

Already in ‘On the Impossible Obligation to Be a Jew,’ which can be read as a reflection on Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1946 book Anti-Semite and Jew, Améry had dealt with the question of what it means to be a Jew. Because he had no positive connection to Judaism in his own life – he was not observant, did not grow up with Jewish traditions, knew neither Yiddish nor Hebrew – he spoke of the impossibility of being a Jew and deliberately avoided writing about his Judaism or his Jewishness. Instead, he used the uncommon term ‘Judesein’ (German for ‘being a Jew’). He could not escape it. The antisemites persecuted him as a Jew, no matter how he viewed himself, no matter what he said, and no matter what he did. What united him with all Jews – whether religious or not, whether they were aware of it or not – was the threat of the ‘death sentence.’[8] This threat, an acute one, constituted the obligation to be a Jew.

In Sartre’s work as well, ‘the Jew’ is defined as someone whom others regard as a Jew and who has to act and live accordingly. What is central to the French existentialist’s philosophy, however, is the possibility of choice. Sartre assumes that all people have the freedom to choose. He distinguishes, without any value judgment, between the ‘authentic’ Jew, who ‘is the one who asserts his claim in the face of the disdain shown toward him,’[9] and the ‘inauthentic’ Jew, who denies his reality and ‘has succumbed to the myth of the “universal human being.”’[10] According to Sartre, Jews can recognise that the world is ill‐contrived and choose to do whatever they think is right to do.

Améry criticises this view of Sartre, whose work significantly influenced his own thinking after Auschwitz, and refutes the notion of a Jewish freedom of choice: ‘I am at liberty to choose myself as a Jew, and this liberty is both a uniquely personal and universal human privilege. Or so I am told. Do I really have this freedom? I believe not.’[11]

Sartre’s error was that ‘in his short phenomenological outline, he was unable to offer a comprehensive account of the crushing pressure exerted by antisemitism and its ability to cajole the Jews into acquiescence. In fact, I suspect that the great author never fully grasped its irresistible force.’[12] Améry is pointing out that Sartre overlooks the qualitative change in the situation of the Jews as a result of the Shoah. For Jews at that time, the world was an opposite world – ‘death was the rule, life an anomaly.’[13]

Because ‘the world was content with the position the Germans had assigned to us,’[14] Jews could no longer depend on the goodwill of others as a vital condition for survival. According to Améry, being a Jew not only means ‘bearing within me the catastrophe that has occurred and may conceivably recur,’[15] but also that ‘[e]very day anew, I lose my trust in the world … human rights declarations, the democratic constitutions, the free world and free press – all this seems too good to last. Nothing can lull me into the sense of security again of which I was disabused in 1935.’[16] When the matter is put to the test, it is not human rights or democratic constitutions that protect against antisemitism, but physical defence alone. That is why Jewish sovereignty is so important to Améry: a state with an army.

For him, the existence of the Jewish state is also crucial because it means that Jews no longer have their self-image impressed on them by the antisemite:

It is the country where the Jew is not a usurer but a farmer, not a pale stay-at-home but a soldier, not a wholesale merchant but a craftsman. Thanks to the state of Israel, the Jews in the Soviet Union and the United States, in France and wherever else the winds of the diaspora may have taken them, have grasped that they are human beings like all others.[17]

However, for Améry the Jewish left-wing intellectual is not free in his choice – which is not actually a choice – with regard to Israel. He is dependent on the Jewish state that guarantees him potential refuge. If this place of shelter is threatened with extinction, there is no alternative but to ‘commit’ oneself to Israel.

Regardless of whether we are entirely of Jewish extraction or not, whether we are religious or totally assimilated atheists, now that Israel is under threat, those of us who have been compelled to recognise that we bear the Jewish lot have been expelled from the community of which we were a part only yesterday … Since hostile armies have massed around Israel, since the most forthright voices in the Arab lands have let it be known that the small country should be turned into a large concentration camp, since there is talk of driving the Israelis into the sea, [the Jewish left-wing intellectual] is no longer a leftist intellectual but merely a Jew.[18]

The ‘authenticity’ schooled by Sartre, to which Améry refers in the last sentence of ‘Between Vietnam and Israel,’ is not one in the sense of the jargon of authenticity,[19] but in the sense of precisely this sentence: ‘… merely a Jew.’ According to Améry’s own idiosyncratic existentialism, authenticity is a negative one – existing only in relation to the death threat. While in the mindset of the racist or the misogynist, the objects of hate still have a place in the world, which they must not leave, for the antisemite Jews, seen as the cause of all evil, have no such place at all.

Against this backdrop, in ‘Between Vietnam and Israel’ Améry criticises a call by French left-wing intellectuals for peace in the Middle East, which condemns American imperialism and emphasises friendship for the Arab people. While the non-Jewish signatories of the appeal, such as Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir can, according to Améry, afford to ‘reaffirm their political and moral principles,’[20] the Jewish signatories are not free to do so because their physical existence is at stake. Among them is the philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch. Particularly in view of Jankélévitch’s own sharp criticism of antisemitism and his regarding Zionism as the continuation of the Résistance,[21] it is incomprehensible to Améry why he is prepared to make concessions to those who want to erase Israel.

What is the point of professing one’s friendship with the Arab people when they are quite obviously not interested in this declaration of love …? What is the point, in this context, of condemning American imperialism? … this has nothing to do with the crisis in the Middle East, where it is, after all, not the Americans who are threatening to wipe out a small country[22]

writes Améry. It will be a rude awakening for Jewish left-wing intellectuals ‘when they are confronted with the incontrovertible fact that they are in no position to choose or take a stance because they have already been chosen and put in their place.’[23]

Left-Wing Anti-Zionism

When writing ‘Between Vietnam and Israel,’ Améry could not have foreseen how the war would end and what developments the hatred of Israel would take in the non-Arab world – most notably in Germany, which Améry continued to observe with the heightened attention of an outcast forcibly removed from that cultural orbit.[24] The year 1967 was a turning point because the grave threat to the life and limb of Jews in Israel became apparent, and also because those sections of the West German left who were not Soviet loyalists and who had been relatively sympathetic to the young Jewish state in the first two decades after the Shoah suddenly turned against Israel with an extraordinary ferocity.

It was as if Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War, which in view of the unequal balance of power could only be won for Israel by a surprise attack, had opened an outlet for repressed resentments in the West German left. According to Améry, their previous solidarity with Israel had served their own needs – of assuaging guilt for the Holocaust – rather than providing a true insight into the persistence of antisemitism and the death threat it carries.

For years, to take the German case, one celebrated the armed Israelis and, not least, the stylish girls in uniform, tilling the Israeli soil. Obvious feelings of guilt were thus discharged in a tainted currency, which was always going to become tiresome. Fortunately, for once, the Jew, instead of being burned, has now emerged as the imperious victor and occupying power … [Germany] breathed a sigh of relief,[25]

as Améry later interpreted the turnaround.

Large sections of the left, in Germany and elsewhere, who have always followed the mantra of siding with the supposedly weak, now identified the weak with the enemies of Israel. Not only had the Jewish state officially started the war with a pre-emptive attack on Egyptian airfields on 5 June 1967, but the small country, which at its narrowest point measures less than fifteen kilometres from the Mediterranean to the West Bank, which at the time was part of Jordan, also made important military-strategic territorial gains. In the Six-Day War, Israel had quickly and successfully averted the threat it faced and was also in a better strategic position than before. There was no alternative to military victory for Israel. Defeat would have meant its annihilation, or in Améry’s words: ‘Auschwitz II on the Mediterranean.’[26]

The valve was opened, a sigh of relief went through the ranks of the West German left: at last, they could accuse the Jews of being the oppressors; at last, the Germans could feel morally superior. Just as the Nazis had seen the Jews as the ultimate evil that had to be eliminated in order to create a peaceful world, the left henceforth fixated on the Jewish state. Anti-Zionism was no longer just the concern of Soviet loyalists but also of the independent, so-called New Left. They were instrumental in propagating the new antisemitism in public. ‘The barricade [is] united with the regulars against the state of the Jews,’[27] Améry writes elsewhere.

The year 1967 marked the beginning of the steep rise of left-wing antisemitism. In his Anti-Semite and Jew – like Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer in their Dialectic of Enlightenment – Sartre recognised that the antisemitic need determines the judgement of the Jew. Reality is always interpreted by the antisemite in such a way that it satisfies his need. In other words, it is about the antisemite’s projection. ‘Wherever we turn it is the idea of the Jew which seems to be the essential,’[28] according to Sartre, not how Jews really act: ‘If the Jew did not exist, the anti‐Semite would invent him.’[29] The antisemite ‘is obliged to invent its own object,’ write Adorno and Horkheimer, and continue: ‘Paranoia no longer pursues its goal on the basis of the individual case history of the persecutor; having become a vital component of society it must locate that goal within the delusive context.’[30]

Resistant to experience and reflection, the left does not see that at this time ‘three million people are pitted against one hundred million.’[31] Instead, left-wing groups openly called for the murder of Jews and took part in the murder themselves. In 1969, activists in Kiel protested against a lecture by the Israeli microbiologist Alexander Keynan and distributed leaflets with the slogan ‘Strike the Zionist dead – make the Near East red!!’[32]

The leftist activists did not shy away from ideological support for despots or even direct cooperation with Palestinian assassins.[33] They justified this by claiming that the Zionists were the new fascists. And fascism, after it was militarily defeated by the Allied Forces in World War II, was seen as the worst crime of all. The accusation that the Zionists were the new fascists was used to legitimise the own desire for punishment and allowed the young German leftists to delude themselves that they had nothing to do with the Nazis while at the same time carrying on their parents’ legacy. Hitler had given antisemitism a bad name. Hence overtly racial hatred of Jews in Europe, and in Germany in particular, evolved. While anti-Zionism was nothing new – Alfred Rosenberg, the infamous Nazi ideologue, for instance, had claimed that Zionism was the ‘militant wing of world Jewry’[34] – the German left in the 1960s and 70s revitalised the fight against Jewish self-determination.

On 9 November 1969, the 31st anniversary of the November pogroms, the group Schwarze Ratten/Tupamaros Westberlin planted a firebomb in West Berlin’s Jewish Community Centre. They had learned to build the bomb in a Palestinian training camp in Jordan, which likewise served as a training ground for Andreas Baader, Ulrike Meinhof, and Gudrun Ensslin, leaders of the German Red Army Faction.[35] In 1970, a similar arson attack was carried out on the retirement home of the Jewish Community of Munich. Seven Jewish residents, all of them survivors of the Holocaust, were killed as a result. In 1976, German members of the Revolutionary Cells together with Palestinian members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine hijacked an airplane on its way from Tel Aviv to Paris. The plane with its 258 passengers was diverted to Entebbe in Uganda, where the hijackers separated the hostages into Jews and non-Jews and only released the latter.

For Améry, these actions meant the betrayal of his supposed allies. He felt compelled to intervene with numerous essays and other public statements about antisemitism, anti-Zionism, and the left. It is not least due to the loss of his own political home that his criticism is so penetrating and clear. And yet it was largely ignored.[36]

Améry’s fight was a fight against windmills. In 1976, in an interview with the journalist Christian Schultz-Gerstein, he explained:

I was also very disappointed by the left, and I am personally very affected by this, and this disappointment is closely linked to suicidal thoughts. The completely unreflective and rabid anti-Israelism is considered good practice, it is as self-evident as class consciousness that Israel is an outpost of imperialism and must be destroyed. … I feel very connected to the state of Israel because I have known the fate of those who did not have such a place of refuge. … But it is out of the question to say a word about this among the left.[37]

Two years later, Améry took his own life.

Reading Jean Améry after 7 October

What happened on 7 October 2023, and what has been happening since then, have surpassed the Jew-hatred of the 1960s and 70s. Hamas and their supporters invaded Israeli territory, raped, mutilated and slaughtered Israelis and proudly filmed themselves doing so. 1,200 people were murdered in a bestial manner, almost 5,000 were injured in one day alone, and 251 people, mostly Israelis but also foreign nationals whose only ‘crime’ was to be in the Jewish state, were taken hostage into Gaza.

Immediately afterwards, leftist groups throughout the Western world gathered in solidarity not with the victims but with the murderers.[38] Feminist activists either ignored the rapes or treated them as ‘resistance.’[39] The tendency among prominent Holocaust, genocide, and memory scholars to delegitimise Israel by drawing unfounded parallels between the extermination of European Jewry and Israel’s policies toward the Palestinians – already apparent well before 7 October – has intensified over the past two years.[40]

The accusation that Israel is committing genocide is an old classic in the repertoire of anti-Israel protesters. Since 2023, however, this blood libel has made its way into mainstream arts, academia, and politics across the West. It has nothing to do with the facts on the ground, but rather with the own psychological needs of anti-Zionists – we might recall Sartre, Adorno, and Horkheimer. In Germany, the popular chant ‘From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free’ was supplemented by the rallying call, ‘Palestine will set us free.’ The redemptive dimension of today’s anti-Israel activism could not be sounded more clearly. ‘Palestine’ has become the new saviour or – in leftist terms – the new revolutionary subject after the proletariat and the Third World failed to deliver on the hopes invested in them.

A truly humane future, once the aspiration of the left – certainly the left Améry considered himself a part of – appears to have been abandoned long ago. The future that today’s leftist activists on the barricades are striving for as ‘liberation’ will not bring about actual redemption of mankind, but a whole different kind of suffering compared to today – suffering reminiscent of the worst horrors humanity had descended into in the 20th century.

When the Germans and their auxiliaries sought to purify the world from misery, the logic of self-preservation, the basis of all rational thought, turned into the logic of extermination: murder for the sake of murder. As a result of its enactment, the Holocaust remains unprecedented to this day. And yet, another descent into barbarism is not banished in the future as long as the conditions that enabled it prevail.

The only practical objection to the world after Auschwitz and the possible repetition of antisemitic extermination today is the Jewish state. Not international law, not human rights declarations, and not – as in present-day Germany’s case – a questionable raison d’état. The fact that antisemitism is intertwined with society at large, or in Adorno’s and Horkheimer’s words ‘anti-semitism and totality have always been profoundly connected,’[41] removes everyone, Jews and non-Jews, from freedom of choice when it comes to the necessity of Israel.

However, Jews feel the ‘crushing pressure’[42] already today. When some side with antisemites and rationalise antisemitic attacks, this phenomenon is often described as ‘Jewish self-hate.’ But such a perception falls short. Because it is based on a displacement: It suggests that the reason for this behaviour lies within the Jew, when in fact it originates outside, in the pressure of antisemitic society.[43] Jews who turn against Jewish self-determination embody, paradoxically, both resistance against and identification with their persecutor. Resistance, because they try to avert the hate against them, identification because they take on their enemies’ gaze. In the attempt to gain self-empowerment, they overlook that antisemitism is not related to what its objects actually do or not do. The security promised by this identification is in fact no security at all. Non-Jews do not experience this pressure. They make their decision – and this crucial difference is all too easily missed – without duress.

Améry’s disconcerting insight is that ultimately no one who cares about a future in which freedom of choice is possible has any true choice today. This is the uncomfortable imposition which cannot be dispelled by omitting Améry’s essay from posthumously published books.

[1] The cover advertises the book by stating that Améry’s solidarity with Israel was ‘not unconditional’ – a claim that leaves room for the delegitimisation of Israel and thereby broadens the appeal to readers today. The statement could not be further from Améry’s analyses, as will be elucidated here.

[2] Jean Améry, ‘Brief an Helmut Heißenbüttel,’ in: Werke Vol. 8., edited by Gerhard Scheit. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta (2007), p. 165.

[3] Gamal Abdel Nasser quoted from BBC News, June 5, 1967: http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/june/5/newsid_2654000/2654251.stm

[4] Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (2022), p. 29.

[5] Ibid. p. 12.

[6] Ibid. p. 31.

[7] Ibid. p. 28.

[8] Ibid. p. 11.

[9] Jean-Paul Sartre, Anti-Semite and Jew. New York: Schocken Books Inc. (1948), p. 66.

[10] Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (2022), p. 13.

[11] Ibid. p. 10.

[12] Ibid. p. 13.

[13] Miriam Mettler, Conditio Inhumana. Jean Améry und Jean-Paul Sartre,’ in: sans phrase 19/2022, p. 172.

[14] Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (2022), p. 14.

[15] Ibid. p. 20.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (2022), p. 53.

[18] Ibid. p. 30f.

[19] See Theodor W. Adorno’s critique of Martin Heidegger’s existentialism in his 1964 book Jargon of Authenticity.

[20] Ibid. p. 31.

[21] See Markus Bitterolf, „Zu Jankélévitch, zu Israel,’ in: sans phrase 23/2024, p. 79.

[22] Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (2022), p. 31.

[23] Ibid. p. 32.

[24] For Améry, it was the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 that made him aware that there was no place for him as a Jew in the German Reich, that his fellow countrymen did not only want to expel him but want to get rid of him for good. Améry irretrievably lost his cultural home and, following his liberation from Bergen-Belsen, refused to stay in Germany or return to Austria and live among the perpetrators. Instead, he chose to reside in Belgium and observed the successor states to the Third Reich with great perceptiveness from a safe distance.

[25] Ibid. p. 35.

[26] Ibid. p. 32.

[27] Jean Améry, Der ehrbare Antisemitismus,’ in: Die Zeit, No. 30/1969. https://www.zeit.de/1969/30/der-ehrbare-antisemitismus

[28] Jean-Paul Sartre, Anti-Semite and Jew. New York: Schocken Books Inc. (1948), p. 11.

[29] Ibid. p. 8.

[30] Theodor W. Adorno/Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical Fragments. Standford: Stanford University Press (2002), p.171.

[31] Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (2022), p. 71.

[32] Ibid. p. 51.

[33] Palestinian organisations are considered the ‘mentors’ of international terrorism. Between 1968 and 1980, Palestinians were responsible for more international terrorist attacks than any other movement. By the early 1980s, more than 40 different groups from around the world had reportedly been trained in Palestinian camps located in Jordan, Lebanon, and Yemen. See Bruce Hoffman: Terrorismus. Der unerklärte Krieg. Neue Gefahren politischer Gewalt. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer (1999), p. 85f.

[34] Rosenberg quoted from Léon Poliakov, Vom Antizionismus zum Antisemitismus, Freiburg: ca-ira Verlag (1992), p. 64.

[35] See Jason Burke, ‘Resistance is when I put an end to what I don’t like’: The rise and fall of the Baader-Meinhof gang, in: The Guardian, September 18, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2025/sep/18/baader-meinhof

[36] It is in light of this ignorance that Améry’s attempt to make concessions to the left must be viewed. Isolated passages from his essay ‘The Limits of Solidarity. On Diaspora Jewry’s Relationship to Israel’ are now eagerly quoted by anti-Zionists such as Pankaj Mishra in the London Review of Books in order to position Améry against Israel. At the end of Améry’s essay, however, it becomes clear that he by no means abandons his commitment to the Jewish state. Before his death, he wrote another text in which he emphasises, ‘My solidarity with Israel is a means of staying loyal to those of my comrades who perished.’ Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (2022), p. 85. This text was also left out of the German publisher’s 2024 book.

[37] Jean Améry, ‘Enttäuscht,’ in: Die Zeit, No. 10/1981. https://www.zeit.de/1981/10/enttaeuscht

[38] See Alan Johnson, ‘‘Progressives’ and the Hamas Pogrom: An A-Z Guide,’ in: fathom, October 2023. https://fathomjournal.org/progressives-and-the-hamas-pogrom-an-a-z-guide

[39] See Jane Prinsley, ‘Outrage as influential feminist academic Judith Butler calls October 7 murder and rape ‘resistance’,’ in: The Jewish Chronicle, March 7, 2024. https://www.thejc.com/news/world/outrage-as-influential-feminist-academic-judith-butler-calls-october-7-murder-and-rape-resistance-f15cx658

[40] For the time prior to 7 October, see the Second Historians’ Dispute in Germany, which began in 2020. For an example of developments after 7 October, 2023, see for instance Dirk Moses, ‘Education after Gaza after Education after Auschwitz,’ in: Berlin Review, 14/2025. https://blnreview.de/en/ausgaben/2025-09/a-dirk-moses-education-after-gaza-after-education-after-auschwitz

[41] Theodor W. Adorno/Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical Fragments. Stanford: Standford University Press (2002), p. 140f..

[42] Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (2022), p. 13.

[43] See Gerhard Scheit, Für Israel. Vier Kapitel über Souveränität als Einführung in negative Urteilskraft. Freiburg: ca ira-Verlag (2025), p. 279f..