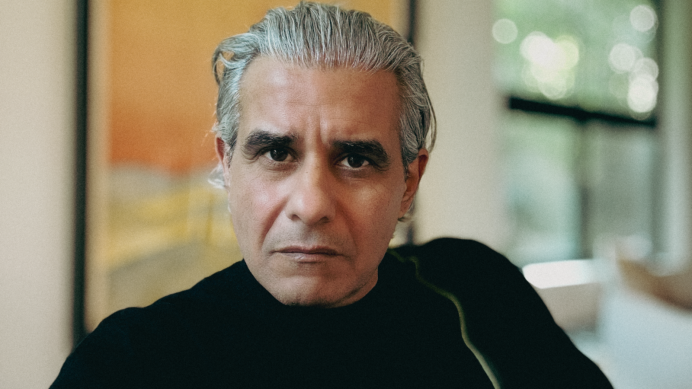

Following news of a ceasefire in Gaza and the return of the 20 remaining living hostages, Fathom asked Israelis and Palestinians to consider issues that both peoples need to grapple with at this time. Mo Husseini is a Palestinian-American writer.

What we Need to Know About Each Other and Ourselves: A Humanist Lens on Asymmetry, Agency, & Accountability

I was invited to respond to two questions. The first: What do Palestinians need to know? The second: What do Israelis need to know?

I said yes, because these are vital questions, deserving of a clear-eyed and human response. But it didn’t take long to feel the framing tug at me. It’s too clean, too balanced, too symmetrical – like we’re dealing with two equal forces failing to meet in the middle. And that, simply, is not the truth, implying as it does an equal knowledge gap on both sides, which, at least from where I stand, is just not what I see.

THE ASYMMETRY OF AWARENESS

We Palestinians don’t lack knowledge. We do not live in a vacuum of misunderstanding. We live, instead, with an overabundance of knowledge. We carry it. We’re governed by it. We know the system that rules over us inside and out. We know every checkpoint, every wall, every restriction. It is a hard-won knowledge, built not from think-tank briefings or policy memos, but from our intimate acquaintance with the systems that dominate our lives and the daily humiliations that stand between us and the mundane desire that we share with Israelis of just getting on with the business of living.

We know exactly how a checkpoint in the West Bank can decide whether you make it to work, to school, to a wedding, or whether you turn around and go home. We know the long shadow of a demolition order, the impossibility of securing the simplest permit, the thud of boots at night. We know the surreal bureaucracy of administrative detention. We know Gaza, even from afar; even before 7 October, the siege had locked it into economic paralysis. And we know that the West Bank’s slow violence – the shrinking land, the expanding settlements, the opportunities choked to death – is just as real. This isn’t ignorance. It’s an awareness carved deep into the bone.

Meanwhile, many Israelis, particularly those within Israel’s borders, live lives that are profoundly insulated from these realities and the consequences of the structures their governments create. This is not about intelligence or capability. It’s about systemic, deliberate, calibrated, and manufactured distance – social, political, and often geographic. And it’s about the stories a nation tells itself to live with policies that produce so much suffering. I’ve sat across from Israeli friends seeing, for the first time, unfiltered images from Gaza – confused, not because they didn’t care or they were uninformed or they were ignoring it, but rather because their media ecosystem didn’t show them. Didn’t let them know.

So, if we’re to be honest, which one hopes is the point of this essay, the greater burden of reckoning sits with those who have more power. It’s not an indictment; it’s a reality.

THE PARADOX OF AGENCY

And insult to injury, even armed with all this knowledge, we Palestinians are still often spoken about, not with. We have almost no acknowledged agency.

This is a crucial distinction: it is not that Palestinians have no agency – we build, we create, we teach, we resist. But this agency is almost never recognised by the structures of power as a legitimate political expression.

Our agency is erased, our resistance flattened into caricatures, our politics dismissed unless they align with what makes others comfortable. This vacuum of acknowledged agency is a core contributor to the conflict; it ensures that the only way to get the world’s attention is through actions that cannot be ignored.

This vacuum is not accidental. The Israeli right-wing, for instance, while not creating Hamas, has often found its existence more than a little politically convenient – a useful counterweight to any pragmatic calls for negotiation, allowing Israel to claim that it has ‘no partner for peace.’

Whatever strategies or visions we craft are hemmed in by a structure of control that extends beyond Israel itself. The levers of change – military, diplomatic, economic – are not in Palestinian hands. Our most fundamental rights are dangled in front of us like toys, handed over or yanked away depending on whether we’ve behaved. There is no negotiation, let alone a negotiation between equals. If you want current proof of this, look no further than the nameplates in front of the seats around the table where the powers that be are deciding the fate of Gaza. Tony Blair FFS? Really?

RECKONING WITH POWER AND RESPONSIBILITY

The idea of a ‘managed conflict’ has long comforted many Israelis. Government policies like ‘mowing the grass’ (כיסוח הדשא) framed the situation as containable, asserting that decades of military dominance would somehow quiet the struggle for dignity and self-determination.

That illusion was shattered on 7 October. Not created by it but shattered by it. The attack did not emerge from a vacuum; it was birthed, instead, in the unaddressed realities of the power dynamics.

Nothing justifies the killing of civilians. Period. The horror and consequent trauma of that day are real, indelible, and must be acknowledged without equivocation.

But if we won’t look at the causal chains of action and reaction, cause and effect honestly, then we’re not seeking peace – we’re looking for comforting fairy tales.

To be explicit and clear: acknowledging the conditions that led to 7 October is not the same as justifying what happened that day.

The conditions? A brutal, decades-long occupation. A blockade that turned Gaza into an open-air prison. A grinding and constant low-grade-pressure status quo designed not to resolve conflict, but to sustain domination. The slow, relentless squeezing of Palestinian life and the application of frictions that ratchet up pressure until only rage or despair remains. Ignoring these conditions or pretending they are ‘not as bad as that’ only ensures the continuation of conflict and suffering.

NAMING HAMAS

Yes, Hamas is a critical part of this story. Yes, its ideology and tactics are destructive, not just to Israelis, but to Palestinians, too. Hamas’ actions on 7 October were horrific. And if you think that naming that is a betrayal of the Palestinian cause, you’re mistaking purity for progress. Hamas has hijacked the cause of liberation, ruling with violence, silencing dissent, and turning resistance into a death cult.

We can, and must, oppose violence against civilians, from any side. We can, and must, challenge the elevation of extremist actors who exploit despair. But let’s not pretend that Hamas emerged in a vacuum, either. Decades of siege, collective punishment, and political failure helped create the soil in which this extremism grew.

THE SYSTEM IS WORKING AS DESIGNED

Let’s also be brave enough to name what we’re actually looking at: for significant portions of Israeli society, particularly the right-wing coalition that has dominated politics for years, the current arrangement is not a failure. It is a success.

It delivers territorial expansion through settlement growth. It delivers a sense of security through overwhelming military dominance. It delivers political power to those who promise strength without compromise. And, most critically, it externalises all the costs, the violence, the humiliation, the despair, onto a population with no leverage to change it.

This is not a failed ‘peace process.’ It is a well-oiled and efficient domination system.

When we talk about Israelis needing to understand Palestinian reality, we speak in language that implies that the problem is one of information. But for many, it’s not ignorance, it’s incentive. Why interrogate a system that delivers you safety, land, and power? Why sacrifice your own tangible benefits (freedom of movement, economic opportunity, the expansion of territory) for the abstract principle of another people’s dignity? Particularly people you really really really don’t like.

There must be a reckoning that doesn’t just ‘see’ Palestinian realities, but acknowledges that Israeli security and prosperity are, in the current structure, built on this reality. It’s policy, not an accident.

Real change doesn’t come from watching a documentary or reading a better news source. It comes from accepting that peace requires giving things up – land, control, the comfort of dominance, the illusion of a purely Jewish state from river to sea. It requires choosing a shared future over an enforced present, even when the present is working for you.

That’s a much harder ask than ‘open your eyes.’ But it’s the honest one.

WHAT ISRAELIS MUST UNDERSTAND

Even the region’s strongest army cannot erase the reasons people resist. Israel cannot bomb its way to peace. It cannot imprison its way to coexistence. It cannot continue expanding settlements and expect Palestinians to wait politely for a state that never comes.

Security bought at the expense of another people’s dignity is not real security – it’s an intermission. It’s a countdown.

In the process of flattening Gaza, Israel is also corroding itself from the inside by normalising authoritarianism and elevating its most extreme voices. This isn’t just about what Israel is doing to Palestinians; it’s about what Israel is doing to itself.

If you think this is unfairly harsh, ask yourself: what would you do if you were born without rights in your ancestral home, under military occupation, watching your land shrink and your hopes die in slow motion? Would you be calm? Would you still believe in process?

Above all, Israelis must understand that there will be no resolution without acknowledging Palestinian identity as real, permanent, and non-negotiable. There will be no final status without Palestinian consent. Imposed solutions don’t last. They metastasise.

WHAT PALESTINIANS MUST UNDERSTAND

Palestinians, in turn, must acknowledge that Israel is not going away. That Jewish attachment to sovereignty and security isn’t just politically powerful – it’s emotionally resonant and embedded, forged by centuries of persecution and trauma and connection to the land itself. Denying this attachment is delusional, self-defeating, and profoundly dishonest.

Palestinians must also demand better of both our leaders and ourselves. What that means is refusing to let despair or anger drive us toward strategies that are cathartic but self-defeating. Rage is not a roadmap. And maximalism dressed up as resistance is a dead end.

Agency in our context is complicated but not absent. What we choose to do with the agency we do have matters, not just because the world is watching, but because we are shaping who we become. The more we allow brutality to be laundered through the language of liberation, the harder it becomes to demand justice without hypocrisy. This includes confronting the elevation of rejectionists, the entrenchment of factionalism, and the erasure of dissent within our own society.

WHAT BOTH SIDES MUST KNOW

We are locked in a sick binary that offers only extinction or supremacy. That’s not coexistence. That’s a perfect and fool-proof recipe for a forever war.

Both peoples will have to abandon fantasies of exclusive ownership. The land isn’t divisible in spirit, only in cartography. You cannot share the land while denying the other’s right to exist on it.

A core part of this is a shared, unequivocal rejection of violence against civilians. For Palestinians, this principle must be applied with the same unflinching honesty. Rejecting attacks on innocents is not just a strategic imperative; it is a moral one. No matter how righteous the cause, this violence dehumanises us, corrodes the moral credibility we need to build coalitions for justice, and warps our own cause. The glorification of this violence is present in our society, too. It is present in the lionisation of attackers who target civilians, whose faces on posters or in celebratory social media posts flatten the distinction between resistance and murder. It is present in the political rhetoric from rejectionist factions that frames the killing of innocents as a celebrated ‘operation,’ silencing dissent. It is present in a communal discourse that, hardened and traumatised by its own suffering, can become numb to the humanity of Israeli victims, viewing their deaths as a justified cost of the struggle.

And this principle must be applied with the same unflinching honesty to Israeli society. The glorification of violence is not always as overt as a victory parade, but it is present. It is present in the lionisation of extremist settlers who attack Palestinian farmers and families, often under the protection of the state, and are hailed as heroes in their communities. It is present in the political rhetoric from government ministers that frames all Palestinians as potential threats, justifying a military doctrine that accepts vast civilian casualties as a regrettable but necessary cost. It is present in a culture that has become increasingly numb to the death of Palestinian children, viewing their lives through the dehumanising calculus of ‘collateral damage.’

For everyone in this conflict, this is not just a moral failing; it is a strategic one. It corrodes the humane values of both peoples and ensures that the cycle of trauma and retaliation continues, making true security impossible.

Most critically, at least from my perspective, both sides must call in (not just out) their own extremists. It’s not enough to shake your head at your Uncle with the shitty and dehumanising memes. You have to call him out. You have to stop allowing him an unchallenged platform. You have to stop handing him the microphone.

We must both understand that safety for one people is impossible without safety for the other. That dignity for one is meaningless without dignity for all. That Palestinian safety, security, and self-determination will never be secured by anything except Israeli safety, security, and self-determination, and vice versa.

This is the handcuff logic of history. We are bound together, spiritually, emotionally, cartographically, and mechanically. The only path forward that doesn’t end in more bodies is the cold, sober, mutual admission: we are here. We are not going away. We cannot break the chain. We don’t have to agree on history to co-author a future. But we do have to show up to write it.

THE BANALITY OF REAL PEACE

I make it a point, as a Palestinian American in the diaspora, to never engage in designing the resolution. Outsiders, who are not on the hook for the outcomes, are all too often eager to offer solutions that don’t understand the nuances on the ground. (h/t to Messrs. Sykes and Picot.)

If you’re outside this conflict and you care, your role is to push – hard – for realistic, pragmatic steps grounded in the equal dignity and rights of both peoples. The goal is not just to stop the shooting. A pause in fighting is a necessary breath, but it is not a breakthrough. As The Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr. said, ‘True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice.’

Justice is two peoples, equal in rights and safety, sharing the same land in a political arrangement they freely choose.

That future will not be heroic or cinematic. It will be boring, bureaucratic, slow, and annoying. It will not look like the climactic final scene of a movie. It will be dull as dishwater. It will look like endless committee meetings, petty arguments about water rights, sewage protocols, joint trash collection schedules, and municipal zoning debates. It will be ugly, imperfect, and deeply necessary.

And it will be worth it.

Because the alternative is more blood.

Because boring beats burying our kids.

A POST-SCRIPT

As I edit this essay, a ‘ceasefire’ of sorts is in place in Gaza. I feel profound relief that the fighting has paused, that hostages are home, and that the skies, for now, are quiet. But this is not cause for a victory lap. This is not peace.

If what we seek is merely ‘no rockets, no bombs, no tension,’ then this moment might feel like a resolution. But if we seek justice – the only foundation for a lasting peace – then this is a breath, not a breakthrough. It is a necessary pause, but it is not the work itself.

The real work, the mundane, bureaucratic, and unheroic work of building that justice, remains before us.