The literary, diplomatic and direct organisational efforts of the British Christian Zionist Laurence Oliphant were central to the coalescence of the first Zionist movement, Hovevei Zion, in the early 1880s. About this precursor of Herzl, and an important influence upon him, the historian of Zionism Nathan Gelber wrote, ‘In cities and small towns in Russia, Romania, and Galicia you could find in the houses of poor Jews a picture of Oliphant.’ Having explored George Eliot’s inspirational role in the emergence of Hovevei Zion in Fathom, Philip Earl Steele now uses neglected Polish sources to reexamine Oliphant’s contribution to the nascent Zionist movement. Steele’s full scholarship on the Christian Zionist component of Hovevei Zion’s origins is available in Polish.

INTRODUCTION

In the first place, it is noteworthy that Hibbath Zion [The Love for Zion] is not an exclusively Jewish idea … There is hardly anything astonishing in the fact that a Gentile can be a Hovev Zion [Lover of Zion] as he can be a Philhellenist. The disinterestedness required makes such allegiance still nobler. In the second place, there is a very close connection between Jewish Hibbath Zion and the appearance and progress of this idea in the Gentile world. Nahum Sokolow, Hibbath Zion, 1935, p. 75.

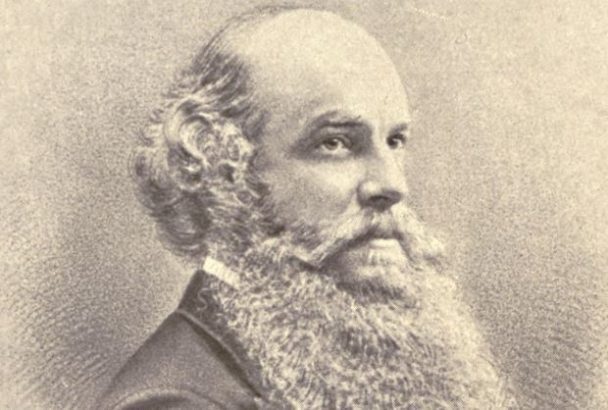

Like Mary Ann Evans/George Eliot, Laurence Oliphant (1829-1888) was raised in the religious atmosphere of Evangelical Christianity. However, unlike Eliot, the adult Oliphant’s faith did not develop along intellectual and emotional lines, but gravitated toward mysticisms that were nominally Christian, though widely considered cultic. Indeed, in 1868 Oliphant caused a scandal when he surrendered his seat in Parliament in order to join the sect of the spiritualist Thomas Lake Harris in Brocton, New York. Ultimately, he was to draw both his mother and his two wives into this adventure. In 1882, during their lengthy and bitter rupture with Harris, Oliphant and his first wife, Alice, settled in Haifa on the northern coast of today’s Israel in order, together with Jewish pioneers, to realise what to outsiders were murky eschatological intentions to redeem the Holy Land.

As both his contemporaries and biographers stress, Oliphant led a double-life from his early adult years. On the one hand he was a seasoned diplomat (and intelligence agent) who for decades enjoyed the trust of the British establishment, as well as a prolific foreign correspondent and writer who was widely admired, and not only in Great Britain. On the other hand, he oft’times succumbed to the allure of curious religious endeavours that astonished people in his own milieux. Much of the riddle of his person seems easy to solve: Oliphant was at least as promiscuous sexually as he was religiously. As a young man he contracted syphilis. This goes far in explaining his submissiveness to Harris, who promised Laurence he could cure him. When we add to this Laurence’s fiery mysticism, it becomes easier to understand ‘the cracks in his cathedral’ such as his readiness to believe in the spiritual salvation of marital celibacy and in ‘sympneuma’, a form of joint breathing the Oliphants came to advocate for people feeling a strong spiritual affinity toward one another. Following his death, The Times wrote what has become Oliphant’s epitaph: ‘Seldom has there been a more romantic or amply filled career; never, perhaps, a stranger or more apparently contradictory personality.’

CHRISTIAN ZIONISM

Christian Zionism is a phenomenon that appeared in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, particularly in its Calvinist form, and is most closely associated with Evangelical Christianity. What is salient here is that Evangelical Christians replaced Catholic saints with the Hebrew prophets and heroes of the Old Testament – ie. The Hebrew Bible. Moreover, the Evangelical belief that the Covenant between God and the People of Israel remains valid (as per Paul’s teaching in Romans 11) soon conditioned Evangelical Christians to see European Jews as Biblical Israelites.

Evangelical Christians also lay great store in Biblical prophecies – a centrally important one being that the Jews would one day restore themselves in their ancient homeland. This belief had accompanied Protestantism on the Isles since the Reformation. However, it became an objective pursued politically not until after the Napoleonic Wars, once Great Britain had become a powerful global empire possessing the means to contribute to the restoration ‘in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people’. Owing to this force multiplier we see a plexus of religious belief and imperial policy on behalf of the Zionist idea that begins in the 1830s. As this paper demonstrates, the Christian Zionist career of Laurence Oliphant (1829-1888) is one of the 19th century’s most illuminating examples of British efforts to restore a Jewish polity in Palestine.

1863: OLIPHANT ACQUAINTS HIMSELF WITH GALICIA

Laurence Oliphant had only freshly returned to England from Italy, when in late January 1863 the Poles rose up against the Tsarist occupation of much of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, dismembered by the Russians, Prussians, and Habsburgs at the close of the 18th century. As Oliphant later wrote, the British government almost at once determined to send him on a mission to observe the fighting. In mid-March he had reached Vienna, and just days later he was in Kraków, where he lodged with his ‘friend’ Adam Potocki, an important leader among the Poles of Galicia, then under Habsburg rule. The first news Oliphant received reported that the Polish armies under General Langiewicz had been shattered, and that Langiewicz himself was under Austrian arrest (19 March, 1863). Having spent roughly a month travelling throughout Galicia, including to Lwów/Lviv, Oliphant departed for Warsaw. After a week of making the rounds there, he managed to join a unit of Polish insurgents. He spent a week with them and then departed for England. However, he returned to Galicia on 13 September of that same year, during which stay he went back to Lwów/Lviv and visited nearby Brody before continuing on to Jassy and other places in Moldova and Romania.

He was to return again to those lands 19 years later – in the wake of the terrible pogroms that broke out in the Pale of Settlement in 1881.

OLIPHANT’S PLAN FOR GILEAD

Oliphant’s parents were adherents of Edward Irving, one of the 19th century’s very most important millennialists, and by that very token a leading advocate of Restorationism, as both Protestants and Jews typically referred to Zionism before Nathan Birnbaum coined the term in 1890. Thus, Oliphant had a lifelong interest in Palestine and its development. Knowing this, in the spring of 1856 Prime Minister Palmerston invited Oliphant to a meeting in London with the Grand Vizier Ali Pasha, Moses Montefiore (Britain’s leading patron of the Jewish community in Palestine), and a few others concerning the construction of a railroad from Jaffa to Jerusalem. A year later Laurence was again to meet with Moses Montefiore, this time for a private lunch described by his assistant Lewis Loewe thus: ‘Mr. Oliphant took a great interest in all matters relating to the Holy Land, and conversed freely with [Montefiore] on certain schemes which might serve to improve the condition of its inhabitants’.

Palestine and restorationism

However, it was in 1878 that Oliphant began to squarely focus his attention on Palestine. Several factors contributed to this. On the one hand was the impasse with his wife Alice, from whom he had been separated for the past two years. For in contrast to Laurence (and his mother), Alice was unable to extricate herself from the influence of Thomas Lake Harris, the leader of the sect they had joined. When in 1876 Laurence fell out with Harris and returned from America to London, Alice remained behind with the Brotherhood of the New Life in Brocton. That autumn she moved to the sect’s new colony in northern California, where Harris had already begun living. This is when he declared himself a new incarnation of Christ and orchestrated the grandiose spectacle in which the lovely Alice was to perform the role of ‘the Lily Queen’, whose precise functions remain unclear. So it comes as small surprise that Oliphant, in searching for a new field of endeavour for his restless energy and feverish mysticism, turned toward the Restorationism he had been raised with. Another factor was that of the changing international situation. This particularly concerned the fears of Great Britain that, following the Congress of Berlin in 1878, Russia (blocked in the Balkans because of the emergence of the new states – namely, Romania and Bulgaria) would now attempt to seize areas in the Levant from the Ottomans.

Thus, combining his religious and imperial motives, Oliphant devised his ‘Plan for Gilead’, presenting it as a way to solve Britain’s worries by establishing a Jewish colony under the protection of Great Britain. In a letter dated 10 December, 1878, Oliphant described his Plan thus:

My Eastern project is as follows: To obtain a concession from the Turkish Government in the northern and more fertile half of Palestine, which the recent survey of the Palestine Exploration Fund proves to be capable of immense development. Any amount of money can be raised upon it, owing to the belief which people have that they would be fulfilling prophecy and bringing on the end of the world. I don’t know why they are so anxious for this latter event, but it makes the commercial speculation easy, as it is a combination of the financial and sentimental elements which will, I think, ensure success. And it will be a good political move for the Government, as it will enable them to carry out reforms in Asiatic Turkey, provide money for the Porte, and by uniting the French in it, and possibly the Italians, be a powerful religious move against the Russians, who are trying to obtain a hold of the country by their pilgrims. It would also secure the Government a large religious support in this country, as even the Radicals would waive their political in favour of their religious crotchets. I also anticipate a very good subscription in America.

Oliphant’s Plan for Gilead soon obtained the backing of Prime Minister Disraeli (a longstanding Zionist), and he in turn swiftly won over Foreign Minister Salisbury. In late November 1878 the three men met together to discuss the idea with the Prince of Wales (the later Kind Edward VII) at Sandringham, one result of which was that Oliphant received his credentials. In February 1879 he set sail for the Levant on a mission George Eliot also expressed approval for. Once in Beirut, Oliphant was joined by Capitain Owen Phipps, who knew the local languages and culture, and the two men headed out to examine the lands north and east of the Jordan river. Once Oliphant had thereby fleshed out his Plan for Gilead, he presented it to the local governor, Midhat Pasha, who promised his active support – on condition that Oliphant obtain the permission of Sultan Abdul Hamid.

SEEKING A FIRMAN IN ISTANBUL

With that aim in mind, in May 1879 Oliphant travelled to Istanbul, where at once he had successes in his contacts with court dignitaries, including the Grand Vizier Heyreddin Pasha, about which he at once informed Disraeli. In his talks with the Turks, Oliphant stressed that Protestants from Great Britain and the United States would provide enormous funding to help realise the aim of establishing a Jewish colony; and he confessed to the Prime Minister that it was difficult to explain to the Turks why that was.

Nevertheless, because of palace intrigues (the Grand Vizier was dismissed in July 1879), as well as a series of tensions in British-Ottoman relations (eg. regarding Egypt), matters came to a halt. The Turkish ministers continued, however, to affirm the assent of the Porte (ie. the central government of the Ottoman Empire), and thus Oliphant decided to remain in Istanbul and await the firman, that is, the Sultan’s permission. During that period he managed to travel to Romania in order meet with Jews there and present them with his plan. These contacts bore fruit over the coming years in the form of close and important ties between Oliphant and those communities. Back in Istanbul, however – in a scene straight out of Kafka’s The Castle – Oliphant waited all autumn and winter for an audience with the Sultan. Seeking leverage, in February 1880 he made a bid for assistance from the Germans, explaining to the British Ambassador to Berlin that Bismarck, were he to push matters forward, would loom in the eyes of Protestants as the agent for the fulfilment of prophecy.

After 11 months of anxious waiting and manoeuvring, the meeting with the Sultan finally took place in April, 1880 – and, as Anne Taylor describes, it was a complete failure. The Sultan explained to Oliphant that he supported the plan for Jewish colonisation, but his ministers were against the idea. Oliphant could not pretend that he believed the Sultan’s words and a heated exchange erupted, prompting one of the Sultan’s attendants to escort Oliphant out to an adjoining room. Henry Layard, the British ambassador to the Porte at that time, later explained that the whole effort to obtain a firman had collapsed because Oliphant had been talking about Biblical prophecies and how the return of the Jews to Palestine was to usher in the return of Jesus – and this was not something the Sultan wished for.

And indeed, throughout his efforts on behalf of the Jewish colonisation of Palestine, Oliphant again and again stressed the advantages that Evangelical beliefs would offer to his plan. A well-known example is from that same year, when he noted that the Jews’ Restoration to the Holy Land was ‘a favourite religious theory’, adding that this fact ‘does not necessarily impair its political value’ but ‘on the contrary, its political value once estimated on its own merits and admitted, the fact that it will carry with it the sympathy and support of those who are not usually particularly well versed in foreign policies is decidedly in its favour.’

In fact, the news of Oliphant’s failed audience with the Sultan was slow to leak out. For example, a newspaper report that was published the next month (28 May, 1880) in Lwów/Lviv in the Gazeta Lwowska revealed no awareness of the failure. What is more notable in that report is the detailed information on Oliphant’s plan – and the use of the term państwo żydowskie – ‘Jewish state’:

Palestine for the Jews! This is the slogan now being repeated here in London with increasing enthusiasm by both practicing Jews and a sizeable number of Christian friends of the Jews. This slogan wins all the more adherents, the weaker the [Sultan’s] power over the Holy Land becomes … The Englishman Oliphant has presented the Sultan with the following plan: the lands of Gilead and Moab, once belonging to the Israelite tribes of Gad, Reuben, and Manasseh, are to be turned into a Jewish colony. It is understood that the Sultan will be paid in jangling gold coins … The Sultan [it has been reported] has expressed himself favourably inclined toward the project … The country [in question] embraces approximately … 600,000 hectares … and is inhabited by nomadic tribes. The colony is to remain under the rule of the Sultan, though it will have an autonomous council and its own governor, no doubt a Jew, as its direct head. In this way the Jews are to return to their own land. This will be the gathering point for the scattered people of Israel – and, as should be anticipated, for a restored Jewish state … Two rail lines are to be built; one from Jaffa to Jerusalem, the other from Haifa to the banks of the Jordan. Sir Moses Montefiore, the widely known Jewish patriarch, has promised considerable sums for the building of the two lines … The New Palestine is to conform to the ideas of the 19th century. But will a sufficient number of Jews be found who wish to settle there?

AWAKENING JEWISH SUPPORT

To Her Royal Highness The Princess Christian Of Schleswig-Holstein Sonderburg-Augustenburg, Princess Of Great Britain And Ireland, The Following Pages Are, By Permission, Most Respectfully Dedicated As A Mark Of Deep Gratitude For The Warm Sympathy And Cordial Interest Manifested By Her Royal Highness In The Author’s Efforts To Promote Jewish Colonisation In Palestine. – The dedication to Oliphant’s The Land of Gilead, 1880, addressed to Princess Helena, daughter of Queen Victoria.

Once back in England, Oliphant completed the work on his book The Land of Gilead, which came out in December 1880. He also pursued his contacts with Romanian Jews – in particular with Bucharest’s newly created Society for the Colonisation of the Holy Land. Oliphant’s efforts in the Ottoman Empire and now the publication of his resulting book made him an all-but universally known figure in the Jewish Diaspora, with the Jewish press extensively, and most often excitedly, reporting on the progress of his plan. For instance, on 9 January, 1880 London’s The Jewish Chronicle, the most important Jewish newspaper in Great Britain, commented on Oliphant’s efforts thus:

It cannot be denied that at no period of our modern history have there been so many forces at work which tend directly to the Great Restoration. Signs and portents abound … Can these be the precursors of the Event? … Mr. Laurence Oliphant’s scheme, detailed by a correspondent in our last week’s issue, contains the most feasible plan that has yet been put before the world.

… At present, the matter is a purely commercial and administrative speculation; but the very practicability and non-sentimentality … is an assurance of its feasibility … It would be a great elevation of the Jewish character in the eyes of the world at large, could they prove themselves capable of conducting a colony, harmoniously and reputably, under the present lawless conditions of Ottoman rule. It must be a peaceful triumph worthy of the days of the Messiah, when all shall be peace … We can go so far as to say that … the scheme recommends itself strongly to the consideration of all earnest and sincere Jews. We shall watch its completer development with intense interest and watchful anxiety … There are persons who think that the Restoration is to be brought about by a supernatural coup de theatre, and that it cannot be accomplished without the intervention of startling and directly apparent miraculous means … There is no reason why all the prophecies, in which the vast majority of us devoutly believe, may not be fulfilled in an apparently natural and consequent manner. To wait for a miracle … is to resemble children who, not strong enough … to assist in the father’s work, wait for him to give them their daily bread, without doing aught to contribute personally to its obtention. To work and to pray is the surest means of accomplishing human aims … Laborare et orare.

THE POGROMS OF 1881-2 AND THE JEWISH REFUGEE CRISIS

Assassins murdered Tsar Aleksander II in Saint Petersburg in March 1881. Their organisation – Narodnaya Volya – was comprised primarily of Russians, though Ignacy Hryniewiecki, who threw the second, fatal bomb was a Pole. Nonetheless – despite the fact that only a single member of the organisation was Jewish (namely, Hesia Helfman, who played a secondary role in the assassination) – it was the Jews who met with universal blame. Hence the terrible wave of pogroms that swiftly engulfed the western provinces of the Tsarist empire that year. Hence also the dozens of associations that came into being by early 1882 – the very first of them having been founded by Eliezer Mordechai Altschuler in Suwałki, northeastern Poland – by the name of Hovevei Zion, ‘The Lovers of Zion’.

Among the Jews fleeing the attacks across the Pale was a steadily rising number of those who crossed the border into Habsburg Galicia, where they gathered in Brody and nearby Lwów/Lviv. The refugees’ living conditions soon began to require humanitarian intervention. During the winter of 1881-82 the British press devoted great attention to their plight. At the initiative of Lord Shaftesbury (the most distinguished British Christian Zionist of the 19th century) and the Archbishop of Canterbury, on 1 February 1882 a boisterous meeting was convened at London’s elite Mansion House, during which urgent help for the refugees was promised. On 7 February The Daily Telegraph reported on its front page that some £10,000 had already been donated. Over the next several months the press regularly reported on the rising sum, The Globe giving a tally of £72,000 on 20 May.

The Mansion House Committee had decided at once in early February that the money would be spent above all in helping the refugees make their way to America – and this compelled Laurence Oliphant to act. He wrote an article for The Times on 15 February explaining that many of the refugees wished to settle in Palestine, where – differently than in America – their religion and way of life would be safeguarded and invigorated. News of Oliphant’s stance spread at once across Europe, with much of the Diaspora again placing its hopes in him. Mansion House responded by drafting Oliphant into its special committee and then dispatching him as a commissioner to Galicia.

On 28 March, while en route to eastern Galicia, Laurence – now reunited with his wife, Alice – arrived in Vienna for a stay that stretched to 10 April. The Polish press, which was monitoring his every move, reported on the 30th that his first meeting concerned the refugee crisis and included F.D. Mocatta of the Anglo-Jewish Association and Moritz Ellinger, representing American Jewry’s ‘Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society’. Gazeta Narodowa described Oliphant himself as:

the author of a work concerning the colonisation of Palestine. His aim is for the Jews to settle the fertile areas to the east of the Jordan. Mr. Oliphant is a Christian, but he has nonetheless eagerly offered his services to the Jewish committee.

Oliphant soon also met Vienna’s Perets Smolenskin, the eminent Zionist activist who published the Hebrew-language journal Ha-Shahar (The Dawn). Smolenskin had been very favourably impressed with Oliphant’s plan for the Jewish colonisation of Palestine and in fact had presented it in Ha-Shahar the previous autumn. In Vienna, in the early spring of 1882, Smolenskin and the Oliphants became friends – Laurence and Alice even invited Perets to travel on with them to Palestine in the aim of fostering the Jewish colonies anticipated to soon arise there. Unfortunately, Smolenskin’s health did not permit that, however Ha-Shahar did go on to energetically endorse Oliphant’s efforts. Smolenskin also expressed his enthusiastic support for Oliphant privately – for instance, when he wrote to the Jewish scholar Ephraim Deinard of his trust for Laurence and Alice, ‘they have only the welfare of Israel in their hearts’; and when elsewhere he stated of Oliphant, ‘if not a Messiah, then a Samson’.

Oliphant also enjoyed the endorsement of Ha-Magid (The Preacher), the outstanding Hebrew-language Zionist journal run by David Gordon in today’s Ełk, in northeast Poland. In late April Ha-Magid published an article written by Oliphant, in which he explained to the weekly’s readers that it wouldn’t be the Jews of Great Britain who would help in the colonisation of Palestine, but rather the Protestants: ‘as soon as your Christian sympathizers in England are convinced the Jews fleeing from Russia can settle with safety in the land of their ancestors, then they will contribute thousands, I may well say, hundreds of thousands of pounds to promote this great object’.

THE OLIPHANTS AMONG THE REFUGEES IN EASTERN GALICIA

By the time Ha-Magid published the article, the Oliphants had been in eastern Galicia among the Jewish refugees for about two weeks. As the Polish daily Czas reported, having left Vienna on the 10th of April, they spent the 11th in Kraków, reached Łwów/Lviv on the 12th, and then immediately began their direct work with the refugees. This was when the Oliphant cult that had been swelling for several years in the Diaspora reached its zenith. He was now widely spoken of as a ‘saviour’ and ‘another Cyrus’. No less than Moses Lilienblum, Leon Pinsker’s closest associate in Odessa, harboured the hope that Oliphant would prove to be ‘the Messiah for Israel’. ‘In cities and small towns in Russia, Romania, and Galicia’, writes the historian of Zionism Nathan Gelber, ‘you could find in the houses of poor Jews a picture of Oliphant. It would be hung right next to the pictures of the great philanthropists Moses Montefiore and Baron Hirsch’.

When Laurence and Alice Oliphant visited Brody, they encountered approximately 1,200 registered refugees and another several hundred unregistered ones. On 19 April they were joined in the work there by Samuel Montagu and Dr. Asher Asher from England, whom the Mansion House Committee had also dispatched to Galicia. These two men, leading English Jews, were also seasoned fellow-travellers, having gone together to Palestine in early 1875 on behalf of the Board of Deputies of British Jews to investigate the living conditions of their compatriots in the Holy Land. But despite this added English presence, along with that of numerous individuals from other, kindred aid organisations, the circumstances on the ground were overwhelming. By mid-May, the emigration fever in the Pale, which Laurence Oliphant had helped fuel, caused the number of refugees to rise 10-fold to 12,000. Indeed, some 7,000 had arrived in the first week of May alone. Oliphant strove to divert as many as possible to Palestine, and not to America. However, the difficulties involved forced him to issue to the Jews of the Pale an appeal, together with the Alliance Israélite Universelle, that they remain where they were for at least the next four months, until such time as the Turks would allow them to settle in Palestine.

During his efforts to orchestrate the safe departure of the refugees in Brody, Oliphant received one delegation after another of so-called ‘Oliphant Committees’, formed by Jews from the Pale enthralled with his seeming power. Here he also met the eminent Zionist activist, Rabbi Samuel Mohilever, then serving the Jewish community in Radom, Poland. It is hardly a surprise that the two men virtually at once understood one another, and soon enjoyed a sincere warmth. Mohilever publicly voiced his approval of Oliphant: ‘Our brethren should not suspect that his intention is to strengthen the Christian religion and divert our people from their faith … He told me that … he and his wife wish only for the fulfillment of the words of the prophets that Israel will be restored to its land, and that they should do this in a way that enables [Jews] to keep every detail of the Jewish religion’. In Brody, Oliphant also met with a representative of BILU, the organisation of young, fervent Zionists (many from Kharkiv) who were determined to settle in Eretz Yisrael as farmers.

Published English-language research on Laurence Oliphant seems to have entirely neglected the wealth of precise information about his whereabouts, exploits, and intentions as found in Polish sources. One of the many pearls to be found in them is from the assimilationist (‘integrationist’) Jewish weekly Izraelita. On 28 April, 1882 Izraelita published a report on the Oliphants written by the Lwów/Lviv correspondent after he had spent time with them among the refugees. Here are important fragments of that article:

As is widely known, the emigration efforts are being led primarily by Mr. Oliphant, the representative of the English committee … The sullen figures pouring out of the rail carriages made an utmost sorrowful sight … the clothing the stricken people wore was no more than rags. One had to witness for oneself how the faces changed beyond recognition when, thanks to the generosity of the relief workers, soon each person donned new clothing! Their gratitude was sincere and quite moving. Mr. Oliphant, in receiving each one of them, issued them registration cards, sharing with each a word or friendly smile. With incomparable cordiality his spouse embraced the poor children accompanying their parents and spoke with the ladies present. The sparse information we have about this virtuous Englishman, who so energetically is executing objectives until recently decried as utopian, is riveting. Sir Oliphant … is renowned … for his extraordinary friendship with the tribe of Israel, this being an attitude altogether typical of a large portion of the English intelligentsia. This is exemplified by the extraordinary religious zeal of the English, as well as by their respect for the people of the Patriarchs and the Prophets … Asked about his religious creed, Mr. Oliphant answered that, although he is a good Christian, he is above all someone sensitive to the suffering of his neighbour.

As far as I was able to discern in my conversation with him, Mr. Oliphant views the Israelites from a Biblical perspective, and that his utmost desire is to contribute to the happiness of our fellow-believers. The committee, which is chaired by the archbishop of Canterbury, initially intended to settle the Israelites in Turkey, but that aim was blocked by the will of the Sultan. Currently the persons emigrating to America are designated, in accord with their hitherto employment, to various professions … This categorisation was underway also here at the train station, and Mrs. Oliphant, who speaks better German [than Laurence], participated in this work together with one of the emigrants who speaks English. At the same time hot meals were being served, and the majority of people passing through here did not disparage any of the food they were given …

In the end, money was also handed out to the poorest. It moved many of those present when one of the refugees pushed the helping hand aside with the words, ‘Thank you, but I still have some of my own money’. This response so pleased the Oliphants that they decided to take that particular Israelite under their personal care, and settle him on their own lands. Would that our own ladies heeded the example of that virtuous woman. Mrs. Oliphant, who is the lady of an English manor and the mistress of vast estates, has endured the discomfort of a long journey to come to the cities of Galicia in order to assist her husband in his endeavours for the good of several hundred needy strangers – Jews, no less!

Of course, the overwhelming majority of the Jewish refugees in 1882 departed for America. The US-based ‘Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society’, which worked closely with the Mansion House Committee, resettled some 14,000 Russian Jews in the wake of the pogroms. The ‘Aid Committee for the Persecuted Russian Jews’ in Lwów/Lviv records having spent Mansion House funds in a sum of 77,000 Austro-Hungarian guldens to pay for train tickets, requisite food, and the like over just the brief period from 30 April to 7 June. As reported on 27 April, 1882 by the Kraków-based newspaper Reforma:

The Russian Jews have no words to express their gratitude to Mr. Oliphant, who – as the second Moses – is leading them out of Muscovite captivity. Numerous Jewish families, protecting themselves from persecution, are now passing through Lwów and Warsaw on their way to America. Mr. Oliphant negotiated such a significant reduction of the travel costs that the journey over land and sea to New York amounts to no more than 45 roubles per person.

THE OLIPHANTS’ ‘TRIUMPHAL MARCH’ TO ISTANBUL

At the very beginning of May, with the Ottomans having banned all Jewish settlement in key areas of Palestine, Oliphant resigned from the mission entrusted to him by the Mansion House Committee. Montagu and Asher remained just a few days longer, and then departed together to Budapest. As Laurence and Alice had planned back in February, they then set out on a journey through Moldova and Romania to Constantinople, intending ultimately to press on from there to the Holy Land in order to assist in the establishment of Jewish settlements. On 4 May, at the final train stop just before the Moldovan border they disembarked. For here in Sadagura/Sadhora Laurence was to meet the great Hasidic rabbi, Avrohom Yaakov Friedman. Oliphant had sought him out, believing the famous rabbi to be ‘the leader of world Jewry’. As Isaac Ewen later recalled, once with Rabbi Friedman in his chambers, Oliphant endeavoured to persuade him ‘to establish a national fund to buy Palestine from Turkey. The rebbe … refused on the ground that he was a Turkish subject … Moreover, he believed Jews must await redemption by a miracle, not by purchasing land.’ Oliphant himself wrote nothing of these proposals and their rejection, but he did share this account that November in Blackwood’s Magazine:

The whole Jewish community of Sadeger awaited our arrival, lining both sides of the street to see the Gentile coming to their rebbe. […] I was led into a room, much like a princely court, furnished with precious gold and silver antiques. There I met the rabbi, accompanied by two servants. Regal authority was in his face … I was … convinced that he could lead and command his people with just the barest gesture.

Oliphant’s pronounced mysticism – indeed, his willingness to believe that Rabbi Friedman was a miracle-worker – had also compelled him to seek an audience with ‘the wonder rabbi’, as he called him:

As the rabbi is by no means the only individual I have come across in the course of my life claiming to have higher gifts than those of ordinary mortals, and as I am convinced in some instances these persons were sincere – and it would be rash, therefore, to assume that such specially endowed persons were all imposters – I am by no means prepared to pass any opinion upon the claims of the rabbi.

The Oliphants’ next stop was in Jassy, in today’s Romania, where, at the invitation of Moses Gaster, Laurence participated together with Romanian Jews in a Hovevei Zion conference:

At Jassy I attended a meeting composed of thirty-nine delegates, representing twenty-eight Palestine Colonisation Societies [ie. Hovevei Zion], who had come at their own expense from the most distant towns in the kingdom. There are forty-nine of these societies altogether, and about 10 000 pounds has already been subscribed, while many of the richer merchants and bankers have promised to contribute when the emigration actually commences. It is advocated in almost all the Hebrew papers published in Russia, and has penetrated the mind of the nation with overpowering force.

In his address to the conference, Oliphant stressed that he supported with his whole heart the attendees’ efforts to organise the settlement of their ancient homeland. Moreover, he explained – no doubt feeling his views had been reconfirmed by Rabbi Friedman – that they could count on enormous sums of money not from Jewish benefactors, but from British Protestants. Later a measure was tabled that Oliphant be made the president of the central committee being formed, but he declined, opting rather to become an honorary member. There at the conference in Jassy Oliphant met the young Nahum Sokolow, who went on to become one of the most illustrious leaders of the early Zionist movement. Years after Jassy, Sokolow recalled Laurence Oliphant as ‘a sincere Christian Hovev Zion’. Laurence and Alice next travelled to Bucharest to attend a similar conference of Hovevei Zion societies, again at the invitation of Moses Gaster. The British press presented Oliphant’s journey to Istanbul as a ‘triumphal march’. In 1887, Laurence himself recalled that period thus:

Five years ago … I … had occasion to visit Brody, this time as the emissary of the Mansion House Committee, for the purpose of distributing relief to some fifteen thousand distressed Russian refugee Jews, who had taken refuge there in a starving condition … I then made the journey from Brody to Jassy by rail; and so intensely wrought up were the expectations of the much-suffering race who form the largest proportion of the population of this part of Europe, that at every station they were assembled in crowds with petitions to be transported to Palestine, the conviction apparently having taken possession of their minds that the time appointed for their return to the land of their ancestors had arrived, and that I was to be their Moses on the occasion.

AGAIN AT THE PORTE, SEEKING A CHARTER

The problems in Istanbul erupted before the Oliphants ever got there – after all, in early May the Turks had barred all Jews from settling in Jerusalem and all Judea. Russia’s May Laws, which two weeks thereafter barred Jews from leaving Tsarist lands, only worsened things. Nonetheless, Laurence refused to give up. He continued corresponding with the Hovevei Zion societies in Romania and the Russian Pale of Settlement, beseeching them to be patient and promising that he would do all in his power to effect a breakthrough. His success proved only partial, and concerned only the Romanian Jews. Specifically, Laurence had discerned a legal loophole: in spite of the Treaty of Berlin of 1878, by which Romania as a state was liberated from Turkish rule, Romania had not recognised its Jews as citizens – ergo they were still subjects of the Sultan. This fact opened the doors to establishing the first new Jewish colonies in Palestine – namely, Rosh Pina and Zikhron Ya’akov (Zamarin), founded in today’s northern Israel in late 1882.

About the Russian Jews, in turn, Oliphant sought the help of the US ambassador, Lew Wallace (nota bene, the author of Ben Hur) – but to no avail. Oliphant promptly conveyed the sad news to as many interested groups as he could, including representatives of BILU with whom he met in Istanbul. The refugees from Russia simply had to wait, and perhaps even return to Odessa (where BILU then had its main office) or to various other cities of the Pale. This was Oliphant’s advice from early June 1882 to the innumerable Jews with whom he corresponded at that time, incurring upon himself ‘a perfectly ruinous bill for postage’. For example, when Oliphant received a letter concerning the chances for settling in Eretz Yisrael from one Moshe Katzinovsky in Pińsk (in today’s Belarus), he responded by saying that right now (2 June 1882) there was no hope the Sultan would change his mind – but perhaps in a few months? ‘For the time being’, Oliphant concluded, ‘I do not advise anyone to move’.

Writing from Istanbul a week later (9 June) to Moses Gaster back in Bucharest, Oliphant blamed his being ‘completely paralysed’ in convincing the Sultan and his ministers to lift the ban on Jewish settlement in Palestine on the crisis then underway between Britain and Egypt (which is why he had solicited the US ambassador for help). Nonetheless, he concluded his letter optimistically, stressing that ‘a great agitation’ was gaining momentum in both England and America – and that the Turks could not put off a favourable solution much longer.

Not incidentally, much of Oliphant’s voluminous letter-writing fell to his private secretary, Naftali Imber, the well-remembered author of Ha-Tikvah (The Hope), sung at the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897 – today the Israeli national anthem. Thanks to his command of nearly a dozen languages, Imber was at once hired as Oliphant’s secretary upon their first meeting in Istanbul. In fact, it was while working for Oliphant that Imber wrote Ha-Tikvah, and he dedicated the volume in which it was published to none other than Laurence and Alice Oliphant. Imber also accompanied them when in late October 1882 they lost all hope in soon changing the Sultan’s decision and sailed off to Haifa. There Naftali lived with them together in their home until July the next year.

The Oliphants were to spend over three years together in today’s northern Israel, during which time they continued to labour on behalf of their dream for a Jewish Restoration in Palestine. Laurence often travelled about Galilee, helping the halutzim (Jewish pioneers) and cultivating ties with them. By a happy fate, this included Eliezer Mordechai Altschuler, the above-mentioned founder of the first Hovevei Zion group, who had come from his native Suwałki, Poland, entrusted with the task of purchasing land for a settlement. In his memoirs, Altschuler wrote:

… it became known that Mr Oliphant was in Tiberias [on the shore of the Sea of Galilee]. This was the Oliphant lauded by all the Jewish newspapers for his love of Israel, his consuming desire being to return the Children of Israel to their Land. He had already written a book in which he set out the idea; he was urging all the important people in England to help the Children of Israel achieve this aim, to which end he had given the settlers many donations and gifts [as an example, Altschuler elsewhere in his memoirs notes that Oliphant gave 1,000 roubles to the founding settlers of Yesud Hama’Ala]. I thought to go and meet this excellent man, so I [and two others] went to where he was staying in the courtyard of the Christian church and announced ourselves. Oliphant ordered his servants to bring us to him. We entered the room where he sat with two of his friends and were brought coffee and smoking tobacco and asked to sit. We told him of our purchase of the [nearby] estate of Arbel, he questioned us about the presence of water there and we told him of the well. We spoke at great length about the principles involved; then we asked him if he could be of any help in preparing the certificates of sale. He told us that he would have helped us willingly but the Turkish Government was suspicious of him, fearing the intrusion of English national interests into our efforts to settle the land. He advised us not to come in great numbers but to settle a few at a time. He further requested us to bring him any antiquities we found in the ruins of Arbel and and said he would give us very good prices for them. We stayed with him for about an hour and then, after he had shaken us by the hand and promised to be of what help he could, we took our leave of him and returned home.

In late December 1885, Laurence and Alice became terribly sick with fever. On January 2, 1886 Alice died. Laurence managed to recover, though not for long. During a visit to London in late 1888 he was discovered to have advanced lung cancer and soon succumbed, just 59 years of age. Naftali Imber was present at Laurence’s funeral in England, directly after which he published a moving obituary of his friend in the Hebrew-language journal Ha-Havatzelet: ‘Mr. Oliphant … the true Lover of Zion, is no longer with us … His love for the people of Israel and its land, a love that had no hidden agenda, a love not dependent on any other cause – this I will relate here’.

LEGACY

In the committed efforts of Laurence Oliphant we have a meticulously prepared plan for the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in the cradle of their religion and culture. It was a plan that won the backing of Great Britain’s Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, and one Oliphant sought energetically to implement by whatever means at his disposal. Moreover, Oliphant’s plan met with the enthusiasm of Jewish communities both across Central and Eastern Europe and in Britain. Over a dozen years after the peak of Oliphant’s Zionist career, the outstanding early Zionist Karpel Lippe recalled Laurence in his review of Herzl’s Der Judenstaat as the first of the great Zionist figures of ‘the old trinity’ – comprised of Oliphant, David Gordon and… himself.

Oliphant’s place in ‘the old trinity’ was secured by the many reasons outlined above – and by others, as well. For instance, as Karpel Lippe well knew, Oliphant had been central to both the establishment and survival of Rosh Pina and Zikhron Ya’akov, settled under the aegis of Lippe, Gaster, and the other Romanian Zionist leaders. Oliphant’s most significant contribution was as a ‘bridge’ until the time when those two moshavot – along with the Yishuv (the Jewish population in the Holy Land) more generally – won the support of Baron Rothschild. In the spring of 1882 a Christian group in Birmingham – the Christadelphians – contacted Oliphant. Once he had arrived in Haifa, they sent him £300 – and then twice that amount in 1883. The Christadelphians wished the money to be used to assist the recently arriving Jewish halutzim and unreservedly trusted Oliphant to know how best to do so. Indeed, the Christadelphians saw him as an instrument in the Divine Plan. Laurence passed all of the money to the settlers of Rosh Pina and Zikhron Ya’akov, and thereby allowed the struggling enterprises to survive until Baron Rothschild’s munificence became paramount in Palestine.

Another reason is that Oliphant – posthumously – helped shape Theodor Herzl’s Zionism as presented in Der Judenstaat and at the first Congresses. Specifically, Herzl rejected the makeshift, piecemeal settlement strategy pursued by the Hovevei Zion movement in favour of a formal charter – this being the very idea Oliphant had relentlessly pursued. Nor was there any coincidence here. In 1895 Oliphant’s friend from Romania, Moses Gaster – later the Haham, ie. the chief Sephardic rabbi in Britain – had described in detail to Herzl the efforts of Laurence Oliphant, and won Herzl over to the charter strategy for achieving a Jewish state. As Gaster wrote:

[In 1882 Oliphant] promised every help and advice, and he went to Constantinople to obtain a Charter for establishing a Jewish colony near Tiberias. This was the origin of the famous Charter of a later kind, when Dr. Herzl was informed by me of the steps taken by Laurence Oliphant, and of the means by which he had hoped to establish an autonomous Jewish colony in Palestine.

Of course, Oliphant did not achieve the political framework for the Jewish colonisation of Palestine he dreamt of. He failed in his bids to obtain the Sultan’s firman, to win a Charter – just as Herzl and the early Zionist Congresses were to, also. Ultimately the matter was to be resolved not until General Allenby entered Palestine in the autumn of 1917 and created the physical basis for the Mandate.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Altschuler, Eliezer Mordechai, These things I Remember, trans. Margaret Myers, Lulu Books, 2007

Amit, Thomas, ‘Laurence Oliphant: Financial sources for his activities in Palestine in the 1880s’, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 139, 3 (2007), 205-12.

Ben-Zvi, M., (compilator), Rabbi Samuel Mohilever, Bachad Fellowship & Bnei Akivah, 1945.

Bloom, Cecil, ‘Samuel Montagu’s and Sir Moses Montefiore’s Visit to Palestine in 1875’, The Journal of Israeli History, vol. 17, no. 3, 1996, 263-81.

Buckle, George Earle, The Life of Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield, vol. VI, 1876-1881, The MacMillan Co., New York, 1920.

Central Zionist Archives, BK/14215/1,2,3.

Dawidowicz, Lucy S., The Golden Tradition: Jewish Life and Thought in Eastern Europe, Beacon Press, Boston, 1967.

Dubnow, S.M., History of the Jews in Russia and Poland, vol. II, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1918.

Encyclopaedia Judaica, eds. Fred Skolnik, Michael Berenbaum, MacMillan Reference, Detroit. 2007.

Fleishman, Avrom, George Eliot’s Intellectual Life, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2010.

Frankel, Jonathan, Prophecy and Politics: Socialism, Nationalism, and the Russian Jews, Cambridge Univ. Press, New York, 1981.

Gaster, Moses, ‘Pinsker’s Auto-Emancipation – A Jubilee’, Views: A Jewish Monthly, Vol. 1, No. 1, London, April 1932, 17-25.

Gaster Collection, Box 2 UCL0001773 1882/10/54, University College London.

Goldman, Shalom, Zeal for Zion: Christians, Jews, & the Idea of The Promised Land, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2009.

Goldstein, Yossi, ‘The Beginnings of Hibbat Zion: A Different Perspective’. AJS Review, New York 2016, 33-55.

Green, Abigail, Moses Montefiore: Jewish Liberator, Imperial Hero, Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2010.

Klier, John Doyle, Russians, Jews, and the Pogroms of 1881-1882, Cambridge Univ. Press, New York, 2011.

Komitet pomocy dla prześladowanych rossyjskich Żydów we Lwowie: wykaz za czas od 30. kwietnia do 7. czerwca 1882. Lwów 1882, 23 s. Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Sygn. 62352 II.

Lewis, Donald M., The Origins of Christian Zionism: Lord Shaftesbury and Evangelical Support for a Jewish Homeland, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2010.

Laskov, Shulamit, ‘The Biluim: Reality and Legend’, Studies in Zionism, Vol. 2, 1981, 17-69.

Loewe, Louis, Diaries of Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore, Belford-Clarke Co., vol. II, Chicago, 1890.

Markowski, Artur, ‘Anti-Jewish Pogroms in the Kingdom of Poland’, Polin Studies in Polish Jewry, vol. 27: Jews in the Kingdom of Poland, 1815–1918, eds. Glenn Dynner, Antony Polonsky, Marcin Wodziński, The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2015, 219-55.

Moszyński, Maciej, Antysemityzm w Królestwie Polskim. Geneza i kształtowanie się nowoczesnej ideologii antyżydowskiej (1864-1914), Wydawnictwo UAM, Poznań, 2018.

Nathans, Benjamin, Beyond the Pale: the Jewish encounter with late Imperial Russia, Univ. of California Press, Berkeley–Los Angeles, 2002.

Oliphant, Laurence, The Land of Gilead, with excursions in the Lebanon, William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh–London, 1880.

Oliphant, Laurence, ‘Rabbi of Sadagora’, Blackwood’s Magazine, November, 1882.

Oliphant, Laurence, Sympneumata, or, evolutionary forces now active in man, William Blackwood and Sons, London, 1884.

Oliphant, Laurence, Haifa, or Life in Modern Palestine, Harper & Brothers, New York 1887.

Oliphant, Laurence, Episodes in a life of adventure, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1887.

Oliphant, Margaret, Memoir of the Life of Laurence Oliphant and of Alice Oliphant, his wife, vol. I&II, wyd. II, William Blackwood and Sons, London, 1891.

Period British newspapers: The Daily Telegraph, The Globe, The Jewish Chronicle, The London Daily News, The Manchester Evening News, The Morning Post, The Standard, St. James’s Gazette, The Times, Yorkshire Gazette.

Period Polish newspapers: Czas, Dziennik Polski, Gazeta Lwowska, Gazeta Narodowa, Izraelita, Reforma.

Salmon, Yosef, ‘Ideology and Reality in the Bilu “Aliyah”’, Harvard Ukrainian Studies Vol. 2, No. 4, December 1978, 430-66.

Schoeps, Julius H., Pioneers of Zionism: Hess, Pinsker, Rülf, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin–Boston, 2013.

Shohet, Azriel, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, Stanford Univ. Press, Stanford, 2012.

Sokolow, Nahum, History of Zionism, 1600-1918, vol. I & II, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1919.

Sokolow, Nahum, Hibbath Zion, Rubin Mass, Jerusalem, 1935.

Steele, Philip Earl, ‘Syjoniści chrześcijańscy w Europie środkowo-wschodniej (1876-1884). Przyczynek do powstania Hibbat Syjon, pierwszego ruchu syjonistycznego’, Żydzi Wschodniej Polskiej, Seria VII, Między Odessą a Wilnem: Wokół Idei Syjonizmu, Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, 2019, 105-38.

Taylor, Anne, Laurence Oliphant, 1829-1888, Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 1982.

Hi Phil:

Oliphant must of had a passion to unite his understanding of the OT. Holy Scriptures and the N.T. Your study is very interesting and I would sense had an impact on Herzal and others. His efforts continued to keep the Jewish community and Christians thinking toward what later took place in 1948. The spark of desire became a fire for the Jews. Amazing! God was preparing the place and the people, but it all took time and interested people.

Thank you for sharing the research. Sincerely, Lynn