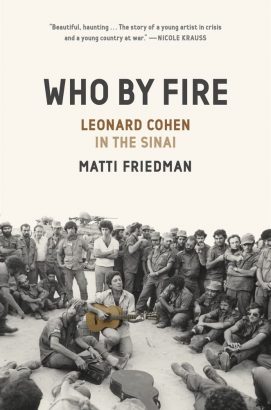

Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai is the latest in Matti Friedman’s wonderful array of books and articles that tell fascinating (and often previously unreported) stories of those aspects of Israeli society unknown to many.

Tracking Leonard Cohen’s journey to Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the book examines, as Friedman notes, ‘the meeting of young soldiers at a moment of extreme peril with one of the great voices of the age’. That meeting was significant for both. ‘Sometimes’, Friedman muses in the book, ‘an artist and an event interact to generate a spark far bigger than both’.

Leonard Cohen would later become a much-loved Fedora wearing gentleman who in his 70’s returned to the road to play hundreds of concerts, opening up his work to a generation of new subsequently adoring fans (including me). But in October 1973 when the Egyptian and Syrian armies launched a surprise attack against Israel, Cohen was a 39-year-old poet-musician at a creative dead end and feeling confined in an unhappy relationship. He had recently announced his retirement from performing. ‘That fall,’ Friedman writes, ‘he felt frustrated perhaps even trapped, not just by his new family and by middle age but by his music. He is in the grip of anger and urges. He’s trying to lose himself with women and drugs.’

After arriving in Israel, Cohen played dozens of concerts in the Sinai desert, as well as some on the western side of the Suez Canal after the IDF has crossed into Africa during the latter stages of the war. The reader is also introduced to an array of characters who cross Cohen’s path: Isaac, the son of Holocaust survivors who rushed back from Tokyo with his Nikon camera (when his elderly father Michael sees him, he expressed his happiness that ‘he came to the war’); the officers from Force Patzi, in the ‘Almond Reconnaissance’ who hunted Egyptian Commandos among the desert dunes; and Yoki and her fiancée Yoram, separated when he was sent to the front but who reunited for an impromptu wedding aboard a ship that Cohen played on.

It’s unclear exactly what the singer planned to do in the country. In one of his diaries – to which Friedman was given access – Cohen proposes to go and ‘stop Egypt’s bullet’. People he met in Tel Aviv were told he intended to work on a Kibbutz, as many volunteers had done during the 6 Day War. Amazingly, he didn’t even bring a guitar. The book proposes he may have been seeking inspiration, seeking what he’d called a “vertical seizure,” ‘a revelation like one the Israelites had experienced long ago in Sinai. This was the place where he thought it could happen.’

When Matti Friedman and I sat down in Jerusalem to discuss the book, he suggested that Cohen was ‘trying to escape his life … He sees Israel’s crisis as a way out of his own crisis. He doesn’t come as Leonard Cohen the musician; he came as a guy who is lost.’

Cohen’s ambivalence about the war is reflected in his description of meeting the ‘Lion of the Desert’, future Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon. ‘Under my breath’ Cohen writes ‘I ask him “how dare you?” But the two drink some cognac sitting on the sand in the shade of a tank and Cohen adds “I want his job.”’

In other places, Cohen had written of how it gave him no pleasure to see young men in uniform. ‘I do not thrill to the sight of Jewish battalions.’ Cohen mused. ‘But there is only one choice between ghettos and battalions, between whips and the weariest patriotic arrogance…’

‘He’s not John Lennon’ Friedman told Fathom. ‘He is not a pacifist.’

But as the war continues, Cohen found himself gaining a deeper identification with the Israelis. He asked those accompanying him to call him Eliezer, his Hebrew name (rather than Leonard).

And it is in this context, between playing concerts at an air force base for weary soldiers, and at a time when as he writes calluses had developed on his fingertips and ‘there were suggestions here and there that I was useful,’ that Cohen wrote of how he ‘began to end a show with a new song… I said to myself perhaps I can protect some people with this song, I would keep it going for a long time.’

That new song was to become the famous and much admired ‘Lover, Lover, Lover.’

Listening to the song now, we hear Cohen’s deep baritone singing ‘May the spirit of this song, may it rise up pure and free. May it be a shield for all of you, a shield against the enemy.’

The intended audience was IDF soldiers going out to war.

Eliezer Cohen was rediscovering the brotherhood of being part of the tribe.

He was trying to stop Egypt’s bullet.

Cohen’s connection to these soldiers and the state they were a part of raised all sorts of questions for him. ‘What if the Jewish solution wasn’t embracing the universal after all, but living in a small tribal state and speaking a language that no one else knew?’ Friedman writes. ‘What if these strange soldiers he’d never met were somehow his brothers?’

Cohen’s thinking is reflected in the ‘missing verse’ of the song ‘Lover Lover Lover’. Behind the song is a mystery that the book unpacks. Soldiers had remembered hearing this verse, and one article in the Yediot Ahronot daily had mentioned it. But no one else had ever come across it.

The verse had disappeared, before being found by Friedman in Cohen’s diary.

It is absolutely startling.

‘I went down to the desert

to help my brothers fight

I knew that they weren’t wrong

I knew that they weren’t right

but bones must stand up straight and walk

and blood must move around

and men go making ugly lines

across the holy ground’

Cohen’s state of mind is there in black upon white. The Israelis have become his brothers.

It isn’t long though before Cohen began to distance himself from this development. Friedman writes of how ‘in the second line, he crossed out the words “my brothers” and instead wrote, “the children.” Then he discarded the verse altogether, and it surfaced only when I found it in the notebook.’

The real turning point comes when the singer saw injured soldiers being stretchered off helicopters after being engaged in battle. ‘I see the bandages’ Cohen wrote ‘and I stop myself from crying these are young Jews dying.’ But then someone told him that the injured are Egyptian (what injured Egyptian soldiers are doing being helicoptered back to Israeli lines is never explained). ‘My relief amazes me’ wrote Cohen. ‘I hate this. I hate my relief. This cannot be forgiven. This is blood on your hands.’

Cohen’s journey changed direction. ‘He has this conflicting approach which begins with a very strong identification with the soldiers and ends with disgust with the war and his own tribal affiliations in the way that war has dehumanised not just the participants of the world but him’ Friedman tells Fathom.

Astonishingly, Cohen later told audiences that he wrote the song for soldiers on both sides during the 1973 war. In one concert in France, Cohen even claimed to have written it ‘for the Egyptians and the Israelis’ in that order.

Perhaps, suggests Friedman, this is part of how Cohen sees his role as a poet. ‘Stepping back from his very emotional identification with one side’ Friedman says, ‘he realises that as a poet he has to be bigger than the Israelis, has to be bigger than the war – he can’t be seen as the bard of one side in one Middle Eastern war.’

There is Cohen the particularist Jew, and Cohen the universalist poet. Never the twain shall meet.

Israelis emerged bruised and battered from the war. Historian Benny Morris argues that Egyptian forces had wiped out the ‘shame’ of earlier defeats and that their ability to conquer and hold on to two strips of territory in Israeli-occupied Sinai, definitively shattered the political military status quo anti-bellum. In the aftermath of the war, Israeli society became less sure of itself. ‘The old servitude of Labor Zionism was destroyed, and the heroism of the founding generation was discredited’ Friedman tells Fathom. The country’s music also changed, becoming more in line with Cohen’s. ‘The upbeat Zionist music with the accordion, that’s all killed by the war’ says Friedman. ‘The country becomes much more inward looking. It’s not about ‘we’ and ideology but about the individual and the soul.’ ‘After the war,’ according to Friedman ‘Israeli music develops an openness to the old wisdom and God which hadn’t really been acceptable to that point – it sounds a lot more like Leonard Cohen.’

Cohen himself was generally mum on his experiences afterwards. In his diary he wrote of how he returned to Hydra, his partner Suzanne and son Adam determined to improve things. ‘I thought I’d try to make a go of it, of this situation,’ he wrote. ‘There was a little child, there was a nice house in Hydra, there was Suzanne, we had a history. And there was so much death and horror in the world, you know? I’m going to tend the little garden. It may not be the garden I wanted and exactly the flowers I planted, but it’s my little garden and I’m going to do my best.’

‘All we can do is note that before the war he said he was retiring and few months after he produces the album New Skin for the Old Ceremony with its very famous songs … so something clearly happened’ Friedman tells Fathom.

Listening to that album today, it’s fascinating to imagine how Cohen’s experiences may have influenced him. In addition to Lover, Lover, Lover, we have Who by Fire, a riff off a Jewish prayer for the New Year and Yom Kippur. Another is called Field Commander Cohen. A third, There is a War. In that song, Cohen sings:

Well I live here with a woman and a child

The situation makes me kind of nervous

Yes, I rise up from her arms, she says “I guess you call this love”

I call it service

Why don’t you come on back to the war, don’t be a tourist

Why don’t you come on back to the war, before it hurts us

Why don’t you come on back to the war, let’s all get nervous

Cohen’s attempt at tending his own little garden didn’t go quite the way he planned. He and Suzanne ultimately separated. But his experience in Israel and the Sinai remained. ‘It’s speculation’ says Friedman, ‘but the experience of playing those concerts – which were a matter of life and death for many – where his songs might have been the last things people heard, that must have had an effect on Cohen. It’s not a stretch to say that the Yom Kippur War is a turning point and major event in Cohen’s life’.

Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai, is out on 29 March 2022.