At the age of 40, having worked as a teacher and an official in the Israeli education ministry while raising a family with her then-husband, the playwright Yosef Bar-Yosef, Hamutal Bar-Yosef switched tracks and began her academic career. She undertook her doctorate at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, though ultimately was never able to secure a permanent teaching position there. Instead, she landed at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, where she taught in the department of Hebrew language and literature from 1987 until her retirement in 2003. In 1993, she became head of the department.

Her academic life was comparatively brief but rather accomplished. Bar-Yosef has published 16 collections of poetry, among them Night, Morning (published in English in 2008) and The Ladder (2014). She has also worked on seven books of literary research, a book of essays, and two collections of short stories. Of The Wall (2019), Aviva Lori wrote in Ha’aretz: ‘There are stories about human weaknesses, small events and great tragedies within a supposedly banal reality, which cause the passing moment to become unforgettable. The prose is written in lean, precise, and unpoetic language. The point of view is factual and critical rather than emotional, sometimes distant and hard to digest.’

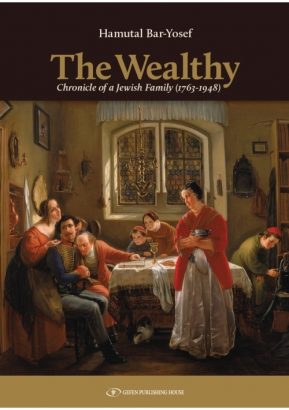

Lori interviewed Bar-Yosef at her home in Jerusalem in 2012. At that time, Bar-Yosef said she was ‘playing around with the idea of writing a novel about the men I met after my divorce’ from Yosef. That idea evidently fell by the wayside; instead, her first novel is The Wealthy: Chronicle of a Jewish Family (1763-1948). Three countries, two centuries, and one family, The Wealthy is an enormous and terrifically ambitious undertaking, one which seeks to describe the great arc of the post-Enlightenment European Jewish experience, the conception of the State of Israel, and how the death of the one dream fuelled the birth of the other.

For her debut, Bar-Yosef has chosen the traditional and rather conservative form of the historical novel. At its centre is the multigenerational saga of the Heimstatt family, whose fate takes them from the precarious existence of a peddler in Prussia in 1763 to wealth, status, and success both economic and political in London at the turn of the twentieth century. Following the First World War, the action moves to Palestine—Britain having been handed the Mandate by the League of Nations—as parliamentarian and businessman Richard Heimstatt becomes deeply invested, both emotionally and financially, in the Zionist cause.

The Heimstatt family serves two purposes for Bar-Yosef. They are an exemplar, a hyper-exaggerated version, of the birth of the European Jewish upper-middle class after emancipation and liberalisation allowed Jews to become citizens, own land, and enter the professions. And, as when Gore Vidal invented the Schuyler family and inserted them into the heart of American power for his seven-part Narratives of Empire series, the Heimstatts are a set of fictional spokes around which real-life characters are caught and revolve. The family are not merely a vehicle for telling a European Jewish story but rather the European Jewish story—as Bar-Yosef understands it.

Bar-Yosef’s best prose is reserved for the front third of The Wealthy. Poets slow the world down and demand our attention, and in The Wealthy’s opening pages, Bar-Yosef displays a poet’s eye for the novel, compartmentalising the narrative episodically in ways that affectively render the struggle and misery of eighteenth-century life. As the novel progresses, Bar-Yosef’s prose loses some of its more admirable qualities as any dramatic or emotional quality is drowned by the research that went into the writing. Peculiar repetitions (‘her neck is thin like the neck of a boiled chicken’) or word choices could have been cleaned up in Esther Cameron’s otherwise-commendable translation.

The Heimstatts economic and societal accession reaches stratospheric levels. Gotthold and Minna Heimstatt, the former having made his fortune in chemicals, emigrate from Germany to England in search of a more liberal and agreeable political climate, purchasing a country estate. Their son, Richard, follows in the family trade—becoming one of the richest men in Britain in the process—and goes on to win a seat in the House of Commons representing the Liberal Party in a constituency in Cardiff. During the First World War, Richard is appointed to the cabinet. His contacts are staggering: Chaim Weizmann, David Lloyd George, and Stanley Baldwin all make appearances in The Wealthy. Few save Herbert Samuel (another actor in the novel) or James de Rothschild can be said to have reached such heights.

The Heimstatts always seem to be in the room where it happens, perhaps to the novel’s detriment, but in any case, Bar-Yosef’s argument would seem to be that the family’s success in Europe came at the expense of their Judaism. Gotthold did not have his son Richard circumcised. Richard is drawn towards the Anglican missionary Jews’ Society, and after he marries a non-Jew, Violette, their children Claire and Ralph are not raised Jewish. Assimilation, Bar-Yosef contends, was the price Jews in Europe had to pay for success, for wealth. In The Wealthy, this was true even in a country where, as Gotthold believed of Britain, ‘anyone can get on if he has talent and is willing to work hard.’

What draws the Heimstatts back towards Judaism is the Zionist enterprise. Though initially sceptical of the idea of a Jewish state in Palestine, Richard Heimstatt becomes both a donor to and a fundraiser for the Zionist movement and politically involved in the Zionist Congress once he loses his seat in Westminster. After the Mandate’s establishment, he is appointed governor of Tulkarm, and like the British Rothschilds (once more, James de Rothschild is a point of reference), Heimstatt invests in Palestine, establishing a citrus plantation in the Sharon plain. Only in Palestine do Richard’s children realise their Jewishness and, having been raised as Christians, enter into the process of conversion.

In the novel’s final third, set in Palestine, the narrative shifts between British, Jewish, and Arab perspectives. The more contemporary the action, the more instructive the novel feels in terms of the ways in which Bar-Yosef seeks to get across the book’s ideas and themes. This section’s most pertinent question comes from Richard’s son, Ralph: ‘Do you have an instrument to measure precisely and evenly the injustice that was done to you and the injustice you have done to others?’ The novel ends with Weizmann in his hotel room in New York, recovering from a heart attack. ‘”Our greatest asset is our restlessness and impatience,” he says to his wife, trying to smile. “I hope we will not settle down too much, now that we have a state.”’