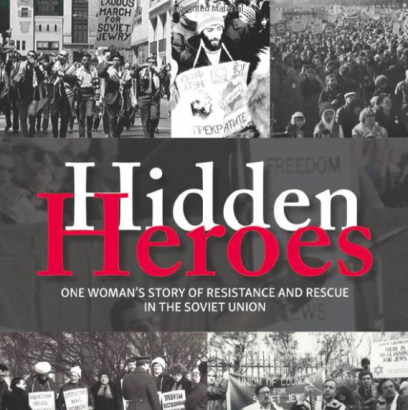

From 1962, when Matzot for Russia’s Jews for the upcoming Passover holiday were dumped on the pavement in front of the Soviet Mission in Manhattan to highlight the cruel restrictions facing their brethren, to the rally of American League for Russian Jews on 19 April 1964 at which Senator Kenneth B. Keating called for a nation-wide petition to be presented to then Soviet Prime Minister Nikita Khrushchev as a protest and remonstrance against anti-Jewish persecutions by the Soviet Union, demanding that the country’s Jews be able ‘to live as a free people or let them leave the country’, to the 1 May 1964 first mass public demonstration initiated by the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry and on to the many, many activities of other activist groups over the next three decades around the world, the Jewish people mobilised for a rescue mission unparalleled in modern times by any other national collective. Remarkably, very few books of insiders’ personal reminisces, rather than historical retellings, have been published.[1]

Communist Russia had suppressed the Jewish religion, its practices and the teaching of its values and theology from the beginning of the revolution. Jewish national identity was denied. Synagogues were closed as were Jewish schooling institutions. And all this was accompanied by persecution and punishment. Josef Stalin had pursued anti-Semitic policies such as the so-called Doctors’ Plot. Beginning in the late 1950s and early 1960s, cognizance of this situation began to move Jewish organisations to react but the methods were of the ‘quiet diplomacy’ category. From 1964 on, a strong, imaginative and persistent grassroots activist movement developed, mainly in the United States and England that rallied Jews, non-Jews, politicians and human rights groups to struggle on behalf of Soviet Jewry, foremost their right to their Jewish identity and the right to immigrate if they desired.

The memoirs of that time include Open Up the Iron Door, published by Rabbi Avi Weiss. Morris Brafman, who founded the American League for Russian Jews, and highlighted the term ‘repatriation’, published In Pursuit of Freedom and From Moscow to Jerusalem: The Dramatic Story of the Jewish Liberation Movement. Phil Spiegel’s book was Triumph over Tyranny and Nancy Rosenfeld wrote Unfinished Journey. A Second Exodus: The American Movement to Free Soviet Jews was edited by Murray Friedman and Albert Chernin. And, of course, there was the book that lit the fire, Elie Weisel’s 1966 The Jews of Silence describing his Fall 1965 trip to Russia. Its admonishment, ‘What torments me most is … the silence of the Jews I live among today’ became the call to mobilise and confront the Soviets.

Pamela Cohen’s Hidden Heroes now adds an exceedingly detailed and readable record of some 25 years of global action to liberate the Jews of the former Soviet Union. Pam met Presidents, was in constant phone contact with refusedniks [my preferred term to the usual refusenik[2]] waiting for the visas, visited the USSR constantly and continued to reach out and help after they exited the Soviet Union.

Photo: Natan Sharansky at the book launch of Pamela Cohen’s book in Jerusalem, August 31, 2021 (courtesy Y. Medad)

Photo: Natan Sharansky at the book launch of Pamela Cohen’s book in Jerusalem, August 31, 2021 (courtesy Y. Medad)

After a stint as co-chair of Chicago Action for Soviet Jewry from 1978 until 1986, she became the national president of the Union of Councils for Soviet Jews (UCSJ), the main ‘non-establishment’ group with some 22 chapters. She went to the corridors of the US Congress, into the White House and made frequent trips to the Soviet Union. Pam’s story is more than a personal summing up of what she and her fellow activists did, though the stories, whether of the delivery of the bear fat (pp. 37-38) or the flight from Kyrgyzstan (pgs. 338-339) illustrate just how amazing her experiences were.

We are talking about one of the main Jewish collective community moments of the late 20th century. The book’s dozens of personal narrative reconstructions draw the reader into that moment. For those who participated at any level in the struggle – on the picket lines, the more activist actions such as tossing nails on a London stage during a 1974 performance of the Bolshoi Ballet, which the New York Times’ critic, Clive Barnes, described as having ‘went beyond the decent grounds of peaceful protest’[3], adopting-a-refusednik , tourists to Russia[4], letter-writers, suppliers of clothing and other resalable items and the people in the cramped inadequate offices and the thousands of volunteers and marchers – it was a supreme defining moment of Jewishness: culturally, spiritually, religiously and for our national identity as a people.

Although mentions of the conflict with the Jewish establishment organisations, both Israeli and American, are present, it is only in the fourth chapter that Cohen details the phenomenon. In fact, the fractiousness was there almost from the start and broke open as a result of the first Brussels conference. Cohen puts it starkly: ‘among our activists there was consensus [in 1982], there was no shared vision’ (111) with Israel government officials. Prime Minister Menachem Begin, when pressed by Lynn Singer in 1980 to exert more supervision over the Lishka, officially known as Nativ, and its director, Nehemia Levanon,[5] ‘rebuffed her quickly, simply dismissing the need’. He ‘trusted him implicitly’ was her estimation (p. 101). Justified or not, the long-time clash was almost a mortal blow to the Russian Jews seeking to exit.[6]

Photo: The SSSJ Geulah (Redemption) March, New York, Passover 1966 (courtesy, N. Teman)

Photo: The SSSJ Geulah (Redemption) March, New York, Passover 1966 (courtesy, N. Teman)

Cohen’s willingness to review this chapter of the campaign is admirable. It was back at the end of 1952 when ‘Nativ’ (‘Pathway’ in Hebrew) was formed, in the tightest secrecy, as a Liaison Office or ‘Lishkat ha-Kesher’. Its task of these small unit was, similar to the 1940s Aliyah Bet, the organ supervising the clandestine immigration from Europe to Mandate, was to ‘ingather the exiles’ from the Soviet Union. Its members, posted in Moscow, were to maintain discreet links with Jews they met, to assist them, and, most importantly, of providing them with information on Israel and religious objects so as to encourage their identification with Israel.

The campaign led by the Union of Councils and the other non-establishment groups was multi-tiered, from the political to the cultural, from diplomacy to protests on the streets. Reading Hidden Heroes, it is clear how symbiotic were the two Jewish communities: those on the inside and those struggling to get them out. The refusedniks progressed from Jewish culture, to Jewish history, to studying the Hebrew language, becoming amateur experts on international law and Soviet jurisprudence and on to becoming more spiritual and religiously observant. Many of the leaders and the central activists underwent a parallel experience. And, to a great extent, too many of the establishment figures of Diaspora Jewish leadership displayed a reverse phenomenon, as well as exhibiting an aloofness, fed by being full of themselves, together with a coldness for Jewish shared responsibility.

The travails of the refuesdniks – including forced unemployment, arrests, beatings, trials, prisons, labor camps and family separations experienced over many years, all faced with fortitude and bravery, as related in this volume – eventually strengthened and fortified the Jews of the Diaspora. The activists in North America and Europe and additional locations learned the skills of press relations, lobbying and holding their ground when pressured to give in to demands of Israel or global politics. Cohen treats all this openly, with candor, even if with a bitterness at the memory of so much unnecessary interference with the struggle to rescue Jews in trouble.

The reader must remember, and Cohen assists us here, that this was the period of the Soviet Union, a state in which anti-Semitism had been passed from the Czar to Stalin. This was a communist dictatorship in which the KGB ruled over a cowered population. It was a time far from the imaginings of today’s woke generation. Cohen says her memoir deals with heroes, and it does. The Jews of the Soviet Union – the men and women, the youth, the parents and grandparents of the Prisoners of Zion in the jails and the gulag system – created a historic source of strength for themselves and for Jews abroad.

The strengthening was reciprocal. The Soviet Jewish activists of the late 1960s and early 1970s drew inspiration and combative spirit from Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War while Jews abroad drew on the heroism of the Jews of the Soviet Union to empower themselves and to create a ‘chain of generations’. The activists found that they could speak before crowds, as Cohen discovered. They could organise a rally in a few days. They could supply medicine or other emergency needs within a short time over long distances. They could face down KGB agents and provocateurs. They could block streets and building entrances. They could stand in a makeshift jail cell in Reykjavik’s city center. They could approach their congressman, their Senator, government officials, even their President or a Prime Minister. They could stage a sit-in at the Tass Office in London in March 1971 or, as a Betar group did in February 1976, fly to the Soviet Union and offer themselves in exchange for incarcerated Dr. Mikhail Shtern.[7]

Photo: Newspaper cutting from City News on the three teenagers flying to the Soviet Union in February 1976 (courtesy of Y. Medad)

Photo: Newspaper cutting from City News on the three teenagers flying to the Soviet Union in February 1976 (courtesy of Y. Medad)

It was a superhuman effort and a supreme example of Jewish self-empowerment.[8] As Cohen testifies, the memory of the Holocaust and the failure of American Jewish leadership at the time, and the attempted suppression of the actions of the Bergson Group at that time, was a motivating force. In fact, Cohen’s book provides an extensive treatment of the shared suspicions both camps held of each other, as well as the potential and real damage caused. I was pleased she recalled Jerry Goodman with who many activists, myself included, had some unpleasant interactions with and disappointments in the official communal leaderships (p. 203).

The recent passing of Ida Nudel, known as the Prisoners’ Angel who supplied them with food and encouragement at great personal risk and who was punished with a term in exile, allows me a personal reflection on the role of the visitors to the refusedniks. I had participated in that first May 1, 1964 demonstration and all through my university years it seems as if every two or three weeks there as another or a vigil or a Third Seder at Passover time. In fact, I met my future wife at a Tisha B’Av sit-down fast in August 1967 on the sidewalk in Manhattan outside the Soviet UN Delegation offices.

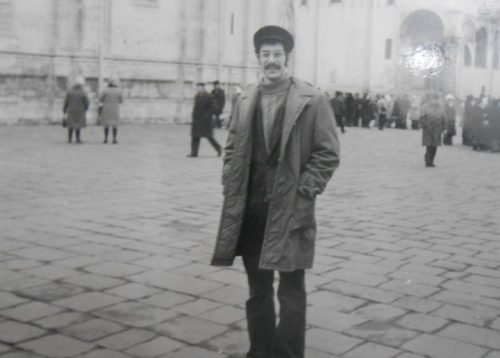

Photo: The author in Red Square, November 27, 1976 (courtesy Y. Medad)

Photo: The author in Red Square, November 27, 1976 (courtesy Y. Medad)

In late November 1976, while serving as the Betar youth emissary in the UK, I and the late George Evnine (who later Hebraised his name to Gershon Yevnin upon coming to Israel on Aliyah) flew off to Moscow after a short seminar provided by Michael Sherbourne who regularly made phone calls to the Soviet Union and was the main source of all our up-to-date information, and receiving a portrait photo of the founder of The 35s, the all-female protest group based in London, but by then chairperson of the Committee for the Release of Soviet Jewish Prisoners, Barbara Oberman[9]. With us were: jeans for resale on the black market, ingredients for the making of long-life nourishment (hard rock candy, Ossem soup tablets and special flour) to be handed to Ida along with razor blades she would use to bribe the guards, Chanukah candles, tapes of the Torah-reading cantillation, Tanach, Hebrew language teaching booklets and more.

Luckily, George had been brought up in a Russian-speaking family and had been employed for a few years in the fur trade, plying the Leningrad-Moscow route. Getting around wasn’t that difficult, even on the underground line, although standing next to two tall and large Russian’s in uniform (of what I never found out) was no fun. The serious portion, which was discussing future plans and strategy in whispers, and on paper quickly destroyed for fear of listening devices, was conducted after meeting Scharansky, Alexander Lerner, the Beilins, Slepaks, a few others. Ida was quite grateful for the cooking materials. Some of what I had brought over such as tapes of songs and Torah cantillations, books and Hanukah candles was impounded at the airport on the way in (and upon our flight out was all returned once I presented the receipt I was given coming in).

Once we left the Beilins’ apartment to go visit Zachar Tesker who, the previous month, had his nose broken during a protest (which led to several of our hosts, including Scharansky, having to spend time in jail), we discovered we were being tailed. I could make out five KGB agents. ‘Five?’ our escort asked. ‘That is good.’ ‘Good?’ I uttered incredulously. ‘Yes,’ he responded. ‘That’s a lot of kopeks they are spending on us.’ Two of them entered the apartment building after us and climbed to one floor above ours, leaning against the railing while we knocked on Tesker’s door.

Our escort’s nonchalant bravado provided me with a lesson I never forgot. These refusedniks[10] were teaching we free Diaspora Jews about what Jewish heroism should be: a devotion to human rights, a commitment to struggle, a willingness to suffer and all for the continuance of the Jewish spirit, the Jewish tradition and the Jewish national idea. What was forcibly hidden by Communist rule was becoming revealed by a cooperation that few, if any other national groupings, had forged.

Pamela Cohen’s book shows us why the term heroism is needed to describe the in the story of Russian Jewry’s fight for freedom, a fight that also transformed their allies among Diaspora Jewry. It is an important read and a necessary one for today’s younger generation of Jews, many of whom appear to prefer applauding false external heroes.

References

[1] A short sample of historical research volumes includes: Gal Beckerman, When They Come for Us, We’ll Be Gone: The Epic Struggle to Save Soviet Jewry, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010; Edward R. Drachman, Challenging the Kremlin: The Soviet Jewish Movement for Freedom, 1967-1990, Paragon House Publishers, 1991; Yossi Klein-Halevy, Memoirs of a Jewish Extremist: The Story of a Transformation, Little Brown and Company, 1995; Fred Lazin, The Struggle for Soviet Jewry in American Politics: Israel versus the American Jewish Establishment, 2005, Lexington Books; William W. Orbach, The American Movement to Aid Soviet Jews, University of Massachusetts Press, 1979; Leonard Schroeter, The Last Exodus, University of Washington Press, 1979. Isi Leibler’s Lone Voice: The Wars of Isi Leibler, also from Gefen Books, adds material from an insider’s view of the Australian scene as well as his interactions on international platforms. A fuller bibliography is here: https://archive.jewishagency.org/russian-aliyah/content/23470.

[2] The Russian term is otkaznik.

[3] As reported in the New York Times on 21 July 1974, https://www.nytimes.com/1974/07/21/archives/what-has-the-bolshoi-done-for-us-lately-dance.html. In an earlier dispatch, he wrote of ‘some brutal morons, completely unauthorized by any Jewish organization, disgustingly threw eggs and nails on the stage and let white mice loose in the audience’. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/07/01/archives/ballet-bolshois-quixote-and-swan-lake-in-london.html.

[4] See, for example, Shaul Kelner, ‘Foreign Tourists, Domestic Encounters: Human Rights Travel to Soviet Jewish Homes‘, In Sune Bechmann Pedersen and Christian Noack, eds. Tourism and Travel during the Cold War: Negotiating Tourist Experiences across the Iron Curtain, London: Routledge, 2020

[5] There is a website with some English content of his here: http://nechemia.org/his%20writings_e.html.

[6] A personal recollection: on the eve of a 1968 march in New York, I was browbeaten along with Yaakov Birnbaum and Glenn Richter of SSSJ by Yoram Dinstein, then working as a diplomat at the Israel consulate and at the United Nations, for pursuing an independent path of protest. For this work, he was described as having ‘earned a reputation for dogmatism’. See: Pauline Peretz, ‘The action of Nativ’s emissaries in the United States’, Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem, 14 | 2004, http://journals.openedition.org/bcrfj/270. An additional study by Peretz with Peter Hägel is here: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066105057893.

[7] He was sentenced by a Ukrainian court on 31 December 1974, to eight years at hard labor on charges of swindling and bribe‐taking. A book, entitled An ‘Ordinary’ Trial in the U.S.S.R., was published by the defendant’s son, August, two years later. See: https://www.nytimes.com/1976/12/17/archives/book-describing-ordinary-soviet-trial-causes-stir-in-paris.html.

[8] On the effect of the campaign on Modern Orthodox Jewry, see, for example Ferziger, A. S. (2012). ‘“Outside the Shul”: The American Soviet Jewry Movement and the Rise of Solidarity Orthodoxy, 1964–1986’. Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, 22(01), 83–130.

[9] On the UK campaign see William W. Orbach, ‘The British Soviet Jewry Movement’, Forum, WZO, Jerusalem, no. 32/33, 1978.