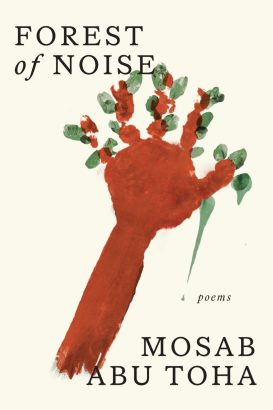

Mosab Abu Toha’s recent volume of poetry, Forest of Noise (Knopf 2024), has excited much complimentary attention as a representative voice from Gaza’s destroyed streets. It has inspired immoderate praise such as, ‘Books are immortal, Palestine is immortal, and I found both aspects of immortality here because these pages capture the resilience and strength of Palestinians.’ Such over-the-top effusiveness pays little attention to what is happening on the pages of this collection.

Abu Toha’s poetry aims at perfect victimisation. The writing depicts not conflict but rather predation by a malevolent power that hovers at the edge of the page. A Palestinian becomes a victim incarnate, one whose survival is a marvel to be admired by readers. Individual death only affirms that survivors will prevail through sheer persistence of national life in the face of evil violence.

Military drones hover ever present above the poems of this collection. They constitute a faceless enemy. There is no need to specify an identity since readers can do that work instead of the poet. The mechanisation of a death force enables attribution to an unnamed but instantly known Jew. Such an unnamed presence in Abu Toha’s poetry constructs an evil juxtaposed to perfected victims.

On the one occasion in this volume where Abu Toha does attempt to imagine an Israeli antagonist, the poem ‘The Last Kiss: On the Way to the Battlefield’ describes a young reservist who kisses his wife good-bye, boards the light rail, and never returns home alive. The matchstick soldier has no interesting dreams or hopes. He exists only as figurative illustration on whom the doors of a train and life itself are closing. No one grieves for Israeli lives, unlike Palestinian lives. The soldier is disposable because he represents injustice. Another poem, ‘On Your Knees,’ figures IDF soldiers as nasty interrogators. There is neither complexity nor humanity in such characterisations. Nothing contributes to reader understandings of why Israeli soldiers are in Gaza in the first place.

What makes this propaganda poetry is a steady refusal to confront the militaristic theo-fascism that has governed Gazan society. If we Palestinians are pure victims, then no part of Gaza political and religious forces can be held accountable for the disasters we endure. The gaze shifts over the border instead of within borders. A partially or wholly invisible malignant force from beyond the border shapes fate: we are not responsible. Poems refuse confrontation with domestic Palestinian governance and responsibilities: all fault lies elsewhere. Unlike Dahlia Ravikovitch’s ‘A Baby Can’t Be Killed Twice’ and its condemnation of Israel’s enablement of the Sabra and Shatilla massacres, Abu Toha refuses to face or mention the 7 October massacre.

Abu Toha’s use of natural imagery attempts to conceal this disjunction between failed social responsibility and violent results. Poetic imagery provides a background scene to Israeli/Jewish violation of nature. ‘The moon overhead / is not the moon,’ (73) Abu Toha concludes a poem describing post-bombing carnage. In propaganda poetry, the violation of a ‘natural’ order in human relations demands a militant response. Thus, in ‘Sunrise in Palestine,’ ‘Fighters smuggle the sunlight / through tunnels / beneath our houses’ (72). Here the theo-fascism of Hamas gains the aspect of a god-like Prometheus delivering fire and light to humanity, not death, destruction, and promised massacre of Jews. The obvious propaganda of such poetic moments shifts Abu Toha from passive avoidance of Palestinian responsibility to active alliance with Hamas. Similarly, Ezra Pound deployed Natura (‘CONTRA NATURA They have brought whores for Eleusis’) and naturalistic imagery in his pre-war cantos to explain his growing alliance with fascism.

The volume’s poetry ignores conflict between two peoples. Instead, single focus and reductionism amount to disinformation more than persuasive poetry. 7 October and all that it entailed disappear behind imagistic mists. Aggressive neighbors, people who occupy stolen land in this poetic landscape, have no right to anger or self-defense. The wholeness of history, actions, and consequences lies abandoned in poems whose motifs circle around grandfather’s well in Jaffa and orange groves that disappeared generations ago. There is no conflict of rights, only the injustice of mass victimisation directed against Palestinians.

In Abu Toha’s public recitations, entire families die and houses get bombed without cause or reason. The fact that a bitter, ugly war in heavily-populated urban terrain causes horrific civilian casualties is not part of the discussion. An originating Palestinian attack that ignited the war does not get mentioned. History-telling skips backward according to nationalistic convenience, not accuracy.

Abu Toha’s poetry, in common with much Palestinian poetry, anchors itself in memories of pre-1948 society. Poems such as ‘Palestinian Village’ express an idyll of rural life and the garden scents of thyme and mint, or in ‘Door on the Road’ a dead young man clutches a key to the family house in Jaffa. Where Abu Toha posits historic continuity, a counter-reading suggests a history of violent rejectionist choices that have led to mounds of rubble in Gaza. The images of rubble and buried bodies that perfuse the poems of this collection originate in revanchist memory that led to disaster.

Forest of Noise pulses with what Abdul R. JanMohamed calls a ‘Manichean aesthetic,’ an aesthetic based on an absolute differentiation between light and dark, good and evil, anti-colonialism and colonialism. In Abu Toha’s aesthetic, essentialised Palestinians, visible in all their pain and sufferings, struggle against death-dealing Israeli colonial darkness. For Abu Toha, Israel entire is Palestine under occupation and negation of that occupation is central to a Palestinian poet’s task. This perspective sets discursive boundaries on humanisation: Israeli suffering and death is not comparable to Palestinian. Negative figuration of Israeli and Jewish humanity derives from rejection of Israel entire – the phrase ‘what is called Israel’ punctuates Abu Toha’s speech – as an inadmissible violation of natural justice.

Abu Toha writes simple images based on a simple claim: there is only one true story, the Palestinian story, my story. There are no questions to be staged, only certainties to be expressed. This is a hallmark of nationalist aesthetics where questions and challenges get construed as lack of patriotism, where a just people suffer unjustly, and where enemies get only what they deserve. Hebrew-language poetry has no exemption from propaganda of this nature. As Ha’aretz (March 26, 2024) reported, the Hineni (‘Here I Am’) series of post-7 October poetry anthologies published by the IDF Chief Education Officer include controversial poems calling for vengeance against the Palestinian people.

The Forest of Noise collection marks a staggering low in Palestinian history, the destruction of Gaza. Unhappily, Abu Toha has not come out of the subterranean tunnels he heroises. He has produced Palestinian momento mori poetry that only memorialises the dead. Abu Toha’s incomplete work fails to criticise the tunnel-builders, despite the disaster they have brought upon the heads of the Gazan people above.