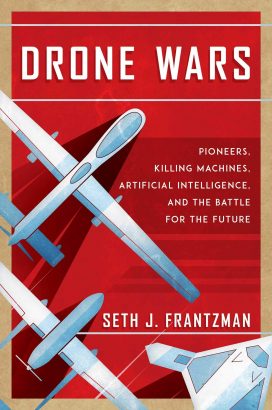

Drone Wars is an ambitious attempt to provide a narrative framework for the development, combat usage and future development prospects of the full spectrum of military UAV types. It is impressive in scope, but ultimately compromised by a lack of consistent detail in key areas, and technical errors and oversimplifications when discussing specific programmes.

The book opens with an overview of Israeli innovations with cheap, simple UAVs for tactical mission sets, and contrasts their success with the abject failure of various US programmes to develop multi-mission UAVs either from scratch or from their extensive stable of target/decoy drones such as the Firebee. It provides a useful contrast between the different approaches to UAS taken by two of the world’s leading manufacturing nations. This is followed by an account of early American efforts to develop and deploy a range of ISR UAVs from Tier I tactical UAVs through Tier III penetrating high-altitude, long endurance (HALE) types. Metaphors including plant growth patterns and evolution are introduced to guide the reader, but since they are applied in a mixed and somewhat throwaway fashion, they do more to confuse than to clarify technical discussions. There are also some notable oversimplifications such as claiming that the RQ-4 HALE UAV was ‘better than the U-2’, without clarification or addressing the fact that at time of publication the venerable U-2 is poised to outlive the RQ-4 in the US Air Force inventory. This first section of the book argues that the US made the concurrent mistakes of over-ambition on its platforms, leading to costs ballooning and programme failure, whilst also accusing it of ‘penny pinching’ and so failing to develop UAVs which could survive against enemy air defences.

The next section provides a succinct but compelling run through the development of the American MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper remotely piloted aerial systems (RPAS) for armed strikes. It charts the move towards arming these aircraft firstly as a practical innovation to shorten the kill chain, but subsequently their growth as a defining element of the War on Terror. There are an impressive number of statistics, and the breadth of research and interviews which the author has conducted on this topic is well evidenced. Given the ambition to explain the technicalities and processes by which the ‘drone wars’ were conducted by the USAF and CIA, however, many of the procedural and technological explanations are basic and limited to vignettes. Readers after a more in-depth account of the evolution of signature targeting and the checks and balances around RPAS as tools of assassination, The Kill Chain by Andrew Cockburn would provide a valuable companion here. After explaining its origins, the author explores the backlash against the US drone assassination programme. He takes the reader through some of the most significant attempts by human rights groups and other international organisations to win justice for those killed in ungoverned spaces outside of recognised conflict zones, and the Obama administration’s multifaceted political relationship with CIA operations. The complex policy imperatives are well brought out, although as elsewhere, the scope of the overall ambition forces Frantzman to tackle these issues within a single chapter, which necessarily limits the level of detail.

Following on from the origins and characteristics of the American drone strikes programme, chapter five turns to the development and proliferation of low-end UAVs and loitering munitions by Iran and its proxies in the Middle East. It also includes first-hand descriptions the ways in which Daesh put its commercial UAV swarms to use in combat in Iraq and Syria. The personal experience of the author shines through in series of compelling accounts of the impact of small UAVs on ground forces. They offer the reader a rare insight into the realities of infantry combat in the new age of commercially available ‘copter’ type UAVs, which will undoubtedly be a significant feature in many conflicts over the coming decades.

The focus on the Middle East continues with an examination of Iranian RPAS development efforts and Tehran’s successful attempts to gain access to downed US RPAS including Predator, Reaper, Scan Eagle and even the secretive stealth RQ-170 Sentinel in 2011. The effects of regional geopolitics on the Iranian policy choices in the drone arena are convincingly woven into Frantzman’s account. However, in its attempt to craft an overarching narrative that UAVs are a driving force behind wider geopolitical events, it sometimes risks misrepresenting correlation as causality. For example, referring to an Israeli F-16 which was shot down by Syrian SAMs in February 2018, Frantzman declares that ‘this is what Iran’s drone war had wrought.’ The F-16 in question crashed while returning from a retaliatory strike inside Syrian airspace following an earlier incursion by an Iranian UAV which was itself shot down by an Israeli Apache. However, both the UAV incursion and the F-16 shoot-down were part of a long term confrontation between Iranian-backed militias, Hezbollah, the Syrian Assad Regime and Israel. Critical context, such as the primacy Iranian-supplied ballistic missiles (as opposed to UAVs) in Israeli threat perception is ignored for the sake of a dramatic narrative flourish. The means by which Iran actually acquired the American RQ-170, and gained access to other crashed US RPASs during the years of the War on Terror and counter-Daesh campaign are also not explored or explained in any detail, and the Iranian ability (or lack thereof) to reverse engineer the complex stealth airframe is glossed over too.

The book does include specific chapter on counter-unmanned aerial system (C-UAS) technology development. Once again, however, the narrative framework is overplayed, opening with a depiction of the Iranian attack on the Saudi Al-Abqaiq refinery as a new Pearl Harbour for the drone age. This ignores the fact that much of the damage at Al Abqaiq was done by cruise missiles rather than the lighter loitering munitions, and that in direct contrast to Pearl Harbour the Al-Abqaiq attack was specifically designed to do symbolic damage without provoking a war. The chapter provides useful information on the strengths and weaknesses of various C-UAS and swarming munition/UAV programmes, but with little in the way of a narrative beyond ‘swarms are coming’. Here at last, however, there is some discussion of the difference between UAVs that require remote control links/GPS to operate and those which are automated and therefore only susceptible to hard kills.

The penultimate section of the book deals with the development of more advanced US drone and unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV) programmes. However, there is insufficient explanation of any of them to allow the uninformed reader to understand their significance and this section is riddled with technical errors. We are offered glib descriptions of the appearance of various UCAVs such as the Kratos Valkyrie as ‘basically…an F-117 stealth fighter with its cockpit cut off’. The author also cites the wrong publication name for one of the articles discussed (The Verge rather than The War Zone) and describes the hypothetical hypersonic SR-72 concept from Lockheed Martin as a ‘sister’ of the operational, subsonic and stealthy RQ-180. Duels between the short-ranged Pantsir S-1 air defence system and Turkish TB-2s are presented as a case study for how UAVs in general can operate against ‘air defences’, without acknowledging the fact that Syrian or Libyan Pantsirs operating alone are hardly representative of even a modestly capable integrated air defence system. The UCAV section continues by taking a confused and often factually inaccurate canter through European and then Chinese UAV and ‘UCAV’ developments. Claims include the perplexing one that ‘China’s new drones could pose the greatest threat [to US air defences] since the Soviet-era MiG-25 Foxbat’, even though the latter was a defensive interceptor and reconnaissance platform which was shown to have very limited capabilities in multiple conflicts during the late Cold War and 1990s.

Where technical details are mentioned, the author displays insufficient understanding to critically evaluate their practical operational capabilities. For example, he repeats a claim that the Chinese CH-5 is ‘more capable’ than the MQ-9 Reaper because it can fly for up to sixty hours, without any discussion of comparative sensor capabilities, weapon envelopes, reliability, altitude performance, ability to operate in adverse weather conditions or a host of other practical considerations. There is also a tendency to overplay Chinese progress, such as citing the CH-7 as a ‘turning point’ in Chinese drone development and Western threat perception, even though beyond a plastic model, there is no public evidence that it has yet flown. China’s GJ-11, by contrast, is given less emphasis in spite of the fact that it has been in flight testing since at least 2013 and is being developed for active service. In his analysis of the recent conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, the author claims Azerbaijan used ‘kamikaze drones to defeat Armenian army units’. In fact the damage to Armenian armour and artillery was primarily inflicted by Bayraktar TB-2 RPAS firing missiles. In this case, Frantzman is confusing air defence suppression activities using loitering munitions with interdiction and close air support.

The thesis presented at the conclusion of the book is that future wars and campaigns should be designed around drones, rather than seeing them as additional or supplementary capabilities. The potential role of AI and autonomy in the development of drones is discussed through speculative vignettes about future clashes between large scale ‘drone’ operators, but again the lack of detailed discussion of operational practicalities and trade-offs weaken its potential impact.

It is clear that the author’s personal experiences under fire with Daesh UAVs as an omni-present threat were a significant factor in motivating him to write the Drone Wars. The book shines during the sections which tell the story of the development and tactical use of small UAVs both by and against various state and non-state actors in the Middle East. The technical aspects are dealt with using a fairly light touch but are for the most part well situated within the broader context of Middle Eastern geopolitics during the decades since the end of the Cold War. Unfortunately the broader ambition of Drone Wars to provide a holistic narrative picture of ‘drone’ development in its entirety falls short. Technical errors and a lack of important details render many of the depictions of higher-end RPAS and UCAV development by the US, European nations and China incomplete at best and misleading at worst. As such, these sections will almost certainly put off many specialist readers. The writing style also jumps backwards and forwards in time, sometimes repeatedly within chapters or sections. This, combined with the sheer breadth of individual programmes touched on, is likely to confuse the more casual reader. In the final analysis, Drone Wars is full of interesting information on a range of important subjects, but is let down by technical errors, oversimplifications and a meandering narrative framework.