Jonathan Schneer’s book The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict was praised by Simon Sebag Montefiore as ‘an excellent and compelling portrait of the intrigues, characters and diplomacy that created the modern Middle East.’ The late Sir Martin Gilbert wrote of it, ‘Why did Britain offer the Jews a home in Palestine? Had they not already offered Palestine to the Arabs, two years earlier? This extraordinarily well-documented and revealing book gives the answers.’ Tony Judt called it ‘the best modern history of the Balfour Declaration.’ Schneer spoke to Fathom’s Sam Nurding about his book shortly before events in London marking the centenary of the Declaration.

Samuel Nurding: Why did you decide to write the book?

Jonathan Schneer: I decided to write the book after reading Margaret McMillan’s Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World, on the Paris peace conference. I wondered what I could do that might have the same impact. Also, I promised my father that I would go through his papers and organise them when he passed away. While doing so I came across a menu dating from the 1920s, from the Waldorf Astoria, a fancy hotel, in New York City. The menu was for a dinner honouring Chaim Weizmann. I realised that my grandfather who had attended this dinner and saved the menu, had been a Zionist. I had had no idea. My grandfather was a prosperous, respectable, upwardly-mobile Jewish immigrant to NYC, who came over in the 1890s. So that piqued my interest. These were the main reasons I wrote the book.

ZIONISM AND ARAB NATIONALISM BEFORE AND DURING THE WAR

SN: What was the state of Jewish and Arab (and perhaps Palestinian) nationalism at the onset of the First World War?

JS: With regard to Jewish nationalism, the modern Zionist movement was founded by the Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodore Herzl, as a response to anti-Semitism. He wanted to help Jews move to Palestine, their historic home, but the Ottomans wouldn’t allow it at least not in great numbers. The main aim of the pre-1914 Zionist movement was first to pressure the Ottomans to allow the immigration of Jews into Palestine in large numbers, and when that failed, to persuade one of the great powers to apply pressure on the Ottomans.

Herzl himself, despairing of quick success, accepted a British invitation for Jews to move in massive numbers to its East African Protectorate. This became known as ‘the Uganda Scheme’. In doing so he split the Zionist movement. There was also a body within the nationalist movement called the ‘Territorialists’. They argued that if Jews were unable to get into Palestine now, they nevertheless needed a safe haven in Uganda, or, indeed, anywhere. In the UK in 1914 there were Territorialists organised in the Jewish Territorial Association (ITO) and there were the Zionists who belonged to the English branch of the World Zionist Organization (WZO). There were about 300,000 British Jews, of whom 8,000 belonged to one or another Jewish nationalist body, and of those 8,000, half lived in London.

As for Arab nationalism, there was not yet a modern Arab nationalist movement as we understand the term nationalism, but there were proto-nationalists. For example, there were pan-Islamists. They hoped that a revived Islam would strengthen] the Ottoman Empire (which was being eaten away by the European powers) and also the Arabs within it. Others called themselves ‘Ottomanists’. They too looked forward to a revived Ottoman Empire (although not necessarily to a religious revival) within which Arabs would play a greater role. And finally there were ‘Arabists’. They looked forward to a stronger Ottoman Empire in which the Arab provinces would have autonomy – something like the Home-Rule that Ireland looked for in the UK in 1914.

After 1908 when the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) took over the Ottoman Empire, Arabism became stronger. There were both above-ground and below-ground Arabist societies. They organised a conference in Paris in 1913, and this is very close to modern nationalism, although the participants were not yet demanding independent Arab states. During this time the Grand Sharif Hussein, who would play a great role in the war and who became what we would recognise as a modern nationalist, was an Ottomanist but he may have already been privately dreaming of an autonomous or even independent Arab kingdom within the Ottoman Empire led by himself.

With regard to Palestinian nationalism, before 1914 there were only a few intellectuals and clerics who were thinking at all of Palestine as a separate entity, and they tended to see the area of Palestine as a territorial bridge linking the Arabian Peninsula with Egypt and Africa. And although they were worried about the Jews immigrating to the area and thus swamping the bridge, there was no organised Palestinian nationalist movement before 1914.

SN: Despite Arab nationalism being in its infancy at the onset of the war, it had much more traction in the Foreign Office than Zionism. So why did the Arabs fail to achieve what the Zionists would later achieve with the Balfour Declaration?

JS: The Arabs did not have more traction in the Foreign Office than the Zionists before the war. Before 1914, the British interest was to have a stable Ottoman Empire. So they regarded Arab nationalists (such as they were) as troublemakers. The war changed everything. When the Ottoman Empire decided to enter on the side of Germany, it became Britain’s enemy too,

and so the British interest turned to how to defeat them. That is why they encouraged Hussein to rebel against the Ottomans. This is why the Arabs gained traction in the Foreign Office.

The answer as to why the Arabs did not succeed in the way the Zionists did is extremely complex. Essentially the Zionists persuaded the British government that Britain had a much better chance of winning the war if so called international Jewry supported them. So the government offered up the Balfour Declaration. That contradicted what they had offered the Arabs. But the Arabs did not have a Weizmann, or Weizmann’s high-powered circle of advisors, to argue their case in London. That may have been the crucial difference.

SN: You write that Zionism’s rise in British foreign policy was far from inevitable. What do you mean by this?

JS: As noted above, during the pre-war years it was in Britain’s interest to keep on good terms with the Ottoman Empire. Ottoman leaders were quite happy for Jews to migrate to the Empire, but they didn’t want a large concentration to settle in Palestine and upset the Arabs. Since this was in the Ottomans interest it was in the British interest too. Once the war began, Britain no longer worried about Ottoman interests. Now it might consider massive Jewish immigration to Palestine if that would help them win the war. If it wasn’t for World War One, however, I don’t know that the British Government would have done that, or that the Zionist movement would have gotten very far, or that there would have been the Balfour Declaration. The Ottoman decision to side with the Germans and Austria-Hungary is what made possible Zionism’s rise.

SN: You dedicate a chapter to the correspondence between Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, and Lieutenant Colonel Sir Henry McMahon, British High Commissioner to Egypt. The Hussein-McMahon correspondence is often cited by people who argue ‘Perfidious Albion’ – i.e. that Britain was engaged in duplicity and double-dealing. What was behind that correspondence and why was it made so ambiguous?

JS: Well, first of all, translating certain words from English into Arabic and vice-versa presented problems. But more basically, both parties intended for the letters to be ambiguous. McMahon self-consciously made promises in order to entice the Grand Sharif Hussein to rebel against the Ottomans. He explained as much in a letter he wrote to Lord Hardinge at the Foreign Office where he explained he was using ‘nebulous’ terms and phrases because the important thing was to get Hussein to act, and Britain should abstain from academic haggling over precise terms.

On the other side, Hussein ignored the ambiguities because he desperately needed British help if he was going to launch the insurrection at all. Now it is true that McMahon pointed out that France might have post-war plans in the Middle East which he could not anticipate and that would have to be dealt with later. That was an unambiguous warning. But if you think about it, it was ambiguous at the same time, because it left open what those French terms might be. Hussein accepted this ambiguity because he didn’t want any conflict with Britain when he was launching a rebellion against the Turks.

THE MOTIVATIONS BEHIND THE DECLARATION

SN: Historians have offered numerous reasons to why the British issued the Balfour Declaration, such as strategic imperial interests regarding the Suez Canal; Christian-Zionist sentiment among British leaders; the desire to court the power of ‘world Jewry’; to stop Jews building their own relations with Germany; to abrogate the Sykes-Picot agreement. How would you rate these factors in terms of importance?

JS: All those played a role. The over-riding aim of Britain during 1914-1918 was to win the war; once Weizmann convinced British leaders that world Jewry, this powerful subterranean world force, could help Britain to that goal then I believe that was what mainly led to the Balfour Declaration. Weizmann further convinced the British that most Jews were Zionists and that Zionists wanted Palestine above all else, and so the British government basically tried to bribe the Jews to their side by offering them Palestine.

SN: Other historians have argued that, in pursuit of its wartime interest, Britain had promised Palestine to three parties – Arabs, Jews and international powers. You write that Palestine was actually a four-time promised land, the last being to the Turks. What was British thinking behind offering continued Ottoman suzerainty over Palestine?

JS: Put yourself in Lloyd George’s place; the question is how to win the war. What’s happening in the Middle East is only a small part of this; he also has to deal with Russia’s collapse on the Eastern Front and he’s trying to deal with the great German threat on the Western Front. He’s got to figure out how to get Britain out of this terrible fix. One small part of the answer was to encourage the Arabs to rebel against the Ottomans; another was to win over world Jewry. But even better would have been simply to detach the Ottoman Empire from the Central Powers. This would have contributed more to winning the war than the support of Jews or Arabs. Therefore, part of the deal he suggested to the Ottomans was to let them keep their flying their flag over Palestine. He was prepared to pay that price. If it had gone that far, the Zionists and the Arab rebels would have thought that Lloyd George had betrayed them. But he could live with that if it meant winning the war.

Sentiment had only a small part to play. Christian Zionists were sentimental about the Zionist cause, and there were men in the Foreign Office who admired the Arabs. However, with the British Empire literally at stake, sentiment was not the most important aspect.

ON CHAIM WEIZMANN, NAHUM SOLOKOW, AND SIR MARK SYKES

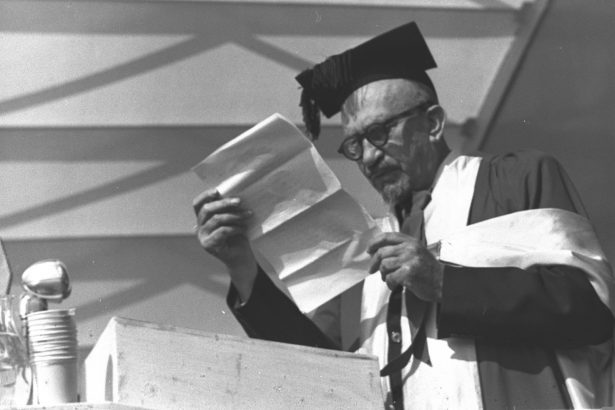

SN: As much as the rise of Zionism was not inevitable in British foreign policy, neither was the rise of its most prominent leader, Chaim Weizmann. What made possible Weizmann’s transformation from chemist to the leader of Political Zionism?

JS: Once again, the starting point is the war. If it hadn’t been for the war who knows if we would be talking about Chaim Weizmann today. But once the war began, why was it that Weizmann and not someone else emerged as the great leader? Well, Weizmann, first of all, saw right away that the British government and the Zionists shared a common goal – to defeat Turkey. He was the man who could really make this clear to both sides.

Additionally, he was a chemist. He figured out how to derive acetone from grain rather than wood. This was a great discovery for the world of British munitions, and it probably expedited Weizmann’s connection with the then Minister of Munitions Lloyd George in 1914.

Moreover, Weizmann had a unique charisma. He charmed one leading British figure after another: C.P. Scott, the editor and proprietor of The Manchester Guardian; Herbert Samuel; Lord Balfour; various Rothschilds.

Here is one of his secrets; he employed a kind of political jujitsu. He used the strength of his opponent to his own advantage. A common anti-Semitic canard was that the Jews had an enormous subterranean power; e.g. over finance in the US or over the pacifist movement in Russia. In effect, Weizmann said to men like Balfour and Lloyd George and Mark Sykes, ‘Yes, we do have that power,’ and he convinced them. This ability to turn anti-Semitism to his advantage, coupled with his extraordinary charm and charisma, probably made him unique even within the Zionist movement. It also probably distinguished him from the leaders of the Arab movement as well.

SN: One of the perhaps forgotten figures in Zionism’s rise is Nahum Solokow. How would you rate Solokow’s importance to Zionism’s success? Were his achievements as important as Weizmann’s?

JS: I think Solokow was extremely important. He served as Zionism’s chief diplomat in the years before World War One. During the war he played a role second only to Weizmann. When the Zionist leaders got together in a hotel in Russell Square to hammer out the wording of the declaration, Solokow was the leading figure.

His other enormous achievement was to extract from the French government and the Italian government statements very similar to the Balfour Declaration. Moreover he obtained from the Pope an avowal of friendship. If I were re-writing the book I would lay greater stress upon Solokow’s achievements.

However, Weizmann remains more important than Solokow. Basically it was Weizmann who corralled the British government behind the Zionist movement – British Zionists believed the British imprimatur was more important than that of any other government. British Zionists looked forward to a British mandate over Palestine, not a French one. They believed that the French would want the Zionists to become French, while the British would allow them to retain their identity as Jews. It never occurred to them to ask the Italians to be the protecting power in Palestine, and the idea of the US in this role, while possibly attractive to them, was not realistic.

It is not clear to me that Solokow could have done what Weizmann did, which was to win over the British power elite to the Zionist idea.

SN: Sir Mark Sykes is most known for his infamous 1916 agreement with French minister Francois Picot. Yet he also had a major role in the story of the Balfour Declaration. How did Sykes view Jewish and Arab nationalism and what brought about a change in his position on Zionism later in the war?

JS: Sykes is indeed a fabulous character. He was born to wealth, the son of a baronet, and had extraordinary social connections and experience. What most marked him out was his self-confidence and imagination, as well as his flexibility and adaptability. If you had met Mark Sykes ten years before World War One you might have thought him a charming advocate of British imperialism, with the conventional ideas that such men then had. He was an anti-Semite and a racist. But he also had an expert’s knowledge of the Middle East from having lived and travelled in the region for many years. I think the Sykes-Picot agreement probably reflects this earlier Sykes. It’s an old fashioned imperial carve up of the Middle East in Britain and France’s interests, with little regard paid to the needs and aspirations of the people who lived in those territories.

And yet this man changed, and in the end he was trying to fit the British Empire into a Wilsonian, liberal, world view. I think he came to sympathise with Arab aspirations for more control over their lives. He came to sympathise with Zionism and the Jews, who he had previously despised.

All that being said, like Lloyd George and Balfour and every other British government figure, Sykes was striving above all for British victory in the war. He came to believe that the Jews and the Arabs could help Britain win the war, which explains the various plans that he later devised.

SN: What are the legacies of the Balfour Declaration?

JS: Well, not in order of importance: Arab nationalists felt that the British had betrayed them by allowing mass Jewish immigration into Palestine. I think they are right to believe that the Balfour Declaration was the opening of a door that had previously been shut, and that was the door to eventual Jewish domination of Palestine. So for the Arabs that is a bitter legacy.

On the other side of the coin, if you were a Zionist then, by opening that door, which is the most important thing in the world, the Balfour Declaration made possible the Jewish state of Israel. Looking at it simply as an historian, the Balfour Declaration was the most significant step towards foreign legitimation of a Jewish state in Palestine.

Weizmann further convinced the British that most Jews were Zionists”

BUT it would be decades before Zionism was popular among world’s Jews.

Ben Gurion solicited Jamal ‘the butcher’ Pasha for a place in his army to fight the Brits, 2/9/1915. He was arrested & sent to Egypt.

The Balfour Declaration was merely an expression of intent that was issued by a state that did not even control the Land of Israel at the time of issuance.

The Mandate for Palestine, however, that was given by The League of Nations to Britain in 1922, was the instrument in secular law that forms the bedrock secular recognition of Jewish national rights in The Land of Israel.