Jeffrey Bernstein reviews a new translation of Theodor Adorno’s 1962 lecture, Fighting Antisemitism Today. What did antisemitism look like in Adorno’s ‘today’; how does it look different in ours; and to what extent are Adorno’s diagnoses and remedies helpful in the fight against Jew hatred today?

Polity Press has recently released Wieland Hoban’s fine translation of Adorno’s intellectually rich 1962 lecture to the German Coordinating Council of Societies for Christian-Jewish Cooperation, entitled Fighting Antisemitism Today. The release could not be more timely, and this itself should give us some pause. If what Adorno says about the commodification of the intellect in the service of the ‘culture industry’ is correct, we would do well to wonder whether the release of this is worth more than simple market value. We will accomplish this by asking whether Adorno’s context mirrors our own current one. On the face of it, the contexts could not be further apart. Adorno writes his lecture less than two decades after the fall of the National Socialist regime, when explicit displays of antisemitism were illegal. We (at least those of us in the United States) live in an atmosphere of growing nationalism and explicit acts of antisemitism. This, however, does not mean that we stand to learn nothing from his text. It is, however, an open question as to what exactly we will learn from it.

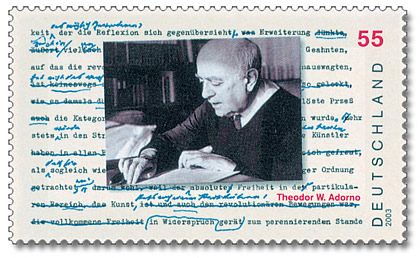

For those who might be unfamiliar with him, Theodor Adorno was born on 11 September 1903 in Frankfurt and died on 6 August 1969 in Visp, Switzerland. Along with Max Horkheimer, Erich Fromm, Herbert Marcuse, and Leo Lowenthal, he was a main member of the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory – first located in Frankfurt, but as a result of World War II, relocated to America. There he co-produced two of the most influential texts of social theory to emerge from the 1940s: Dialectic of Enlightenment (co-written with Max Horkheimer) and the political-psychological social research study The Authoritaraian Personality (authored with many co-researchers). After the war – as a result of not feeling at home in America – Adorno returned to Germany to take up the professorial role that was denied him under the Nazis on account of having a Jewish father (even though he converted). His lecture transcripts (now being released and translated) and magnum opii, Negative Dialectics and Aesthetic Theory were produced late in his life.

Adorno begins his lecture by stating baldly that modern antisemitism is not a simple phenomenon – it is not ‘primordial’. It is part of a ‘ticket’, a ‘platform’ that one buys into when one supports a party or candidate. Specifically, it is part of a nationalist ticket: ‘Whenever people preach a certain kind of militant and excessive nationalism, antisemitism is automatically included.’ It has unified otherwise divergent elements of the right. So the first thing to understand, in Adorno’s account, is that (modern) antisemitism is itself a product of nationalism. Whether Adorno considers all statehood per se nationalistic is an open question. On the one hand, he qualifies nationalism with the descriptor excessive in his pairing of it with antisemitism. On the other hand, as Jay Bernstein has argued, Adorno has little faith that the state (as a result of state capitalism and monopoly capitalism) can actually accomplish much good for society. So it is unclear whether he believes the state as such to be a bearer of antisemitism. He does (as he states in ‘The Meaning of Working Through the Past’) believe that internal fascism is more dangerous at this point than fascism from abroad, and this suggests that he holds the potentiality for nationalist antisemitism to be strong.

This concern over internal fascism is of a piece with Adorno’s concern over the repression of explicit antisemitic expressions insofar as they are driven (as it were) underground but not seriously dealt with: ‘the potential has very much survived. You need only take a look at the far-right press in Germany, which has a considerable number of representatives, to find many statements that could be declared crypto-antisemitic, and whose implications, underlined with a nod and a wink, nurture antisemitism.’ Additionally, parents of children who lived through the war become activated by these crypto-remarks and feel justified in their past National Socialist adherence. Once this happens, they are brought back to the antisemitism of the 1930s. This, then, gets transmitted to the children. In a sense, Adorno’s context is more insidious than our own insofar as the antisemitism is not as blatant. For this reason, Adorno believes that one must address such antisemitic beliefs with ‘militant enlightenment’ – truthful arguments that don’t shy away from addressing the stereotypes in question.

It isn’t that Adorno has nothing to say about radical, explicit, antisemitic expressions. Nor, be it said, is Adorno afraid to call on the help of state authority in such situations. Upon hearing workers express such antisemitic views in public, he immediately notified the police and had them arrested. These, however, are few and far between given the paucity of actual Jews in Germany at the time. Nevertheless, Adorno holds that

we are not dealing only with people whom we can educate or change but also those with whom the die has already been cast, often those for whose specific personality structure [a reference to his political-psychological analyses in The Authoritarian Personality] it is characteristic that they are in a certain sense, hardened and closed to experience, not really flexible – in short, they are unresponsive. One must not dispense with authority when dealing with these people . . . not out of an urge to punish or take revenge on those people but, rather, to show them that the only thing that impresses them, namely true social authority, for the time being still stands against them after all.

We should note that the phrase ‘educate or change’ does a lot of work here. The primary goal is to educate for change. It is (in Aristotle’s words) only for the people who are impervious to education that laws are necessary. Adorno’s view is fundamentally an Enlightenment view.

Arguments carry much weight for Adorno. As Peter Gordon notes in his Afterword to the present volume, Adornean arguments against antisemitism do not take the form of opposing particular claims to antisemitic ones; rather, they break with stereotypical thinking itself. To the claim that Jews carried an oversized influence in Weimar Germany and therefore should not be able to attain to high positions today, Adorno argued against the counterclaim that Jews didn’t have too much influence. Instead, he holds that ‘one must make the case in a . . . radical way: in a democracy, any question regarding the proportions made up in different professions by different demographic groups violates the principle of equality from the outset.’ Adorno believes that this is the way to fight antisemitism today because it raises the prejudice from an unconscious, unthinking passion to conceptual thought: ‘antisemitism is a mass medium in the sense that it taps into unconscious drives, conflicts, inclinations and tendencies that it reinforces and manipulates, instead of raising them to the conscious level and resolving them . . . [antisemitism] is a thoroughly anti-enlightening force’. It is the signal achievement of the Frankfurt theorists to apply psychoanalytic categories to social phenomena, but perhaps because Adorno was working with an early model of psychoanalysis (resistance, unconscious drives, conscious clarity) he thought that a good argument could win the day against antisemitic prejudices. In early psychoanalytic parlance, neuroses can be analysed; psychoses not so much. The question is which category antisemitism falls in on the social register. In the Germany of 1962, the repressed expressions of antisemitism certainly seemed to mirror the neurotic’s circumstance.

To the antisemite’s claims that the murdered Jews could be thought in relation to the German deaths in the firebombing of Dresden, or in the war more generally, Adorno cautions against haggling with numbers or even accepting the premise. Instead, one should reject the comparison of dying in war with ‘the planned extermination of entire population groups.’ The situation is similar with the claim that ‘You’re not allowed to say anything bad about the Jews these days.’ Instead of idealising Jews, one should point out that ‘they have a great, turbulent and wild history containing just as many horrors as the histories of other peoples.’ Better to rob the antisemite of stereotypical thinking as such than to accept their premise and fight on their terrain.

Adorno quickly moves from giving these types of examples to what he terms ‘long’ and ‘short’ term programmes for dealing with antisemitism – ‘the education programme and the immediate prevention programme’. The long-term programme seeks to address the root causes of antisemitism as they occur in the home – as such, Adorno is concerned with childhood education. Again he stresses that we would do well not to treat antisemitism as a ‘primordial’ phenomenon, but to see it as bound up with social dynamics. The aim of education, in this sense, would be to prevent the development of the ‘authority-bound character’. Children who are bullies, who exclude others, and who set up systems of schoolyard authority are to be focused on. Adorno’s hypothesis is that children who are treated coldly, without being able to express affect, without being given the value of speaking for oneself, are the most at risk. These children often become ‘public opinion leaders’ and need to be set straight. The situation becomes even worse if they have parents who are authoritarian personalities and express antisemitic views to their children. For Adorno, these are the ones on whom focus should be bestowed first:

One should concentrate one’s attention on them and try to change them. In cases where there is a strong resistance from home, an educator should not shy away from conflicts with the parents. The educator should teach the children that what they hear at home is not God’s truth, that their parents can be wrong and why. One should expect educators to have the necessary civil courage for such conflicts.’

For my part, I cannot imagine a school administration – in 1960s Germany or today – that would support teachers in open conflict with parents. But Adorno persists. Is he wrong?

Similarly, educators should not allow group dynamics to form into cliques (which, on Adorno’s reading, are simply microcosms of broken society), but instead ‘to encourage individual friendships and not, as certainly still occurs often in school, to treat them with sarcasm and denigration.’ The de-emphasis on cliques would have the effect of deflating the influence of those ‘refractory children, among who also tend towards violence and sadism in other ways. They often hold leading positions in the unofficial classroom hierarchy.’ Another way of deflating these influences is to ‘increase the capacity for expression in general and mitigate the resentment about speaking.’ Being able to form thoughts and speak on one’s own behalf challenges the willingness to blindly submit to authority in favor of conceptual thought. It would also rob the antisemite of the view that Jews alone are ‘clever’ and ‘tied to their intellect’: ‘If it becomes clear that intelligence is not an attribute of a particular group or race or religion but only the quality of individuals, this will already be some help.’

Moving to the short-term programme, Adorno discusses the need for vigorous and intelligent responses to antisemitic statements: ‘One must oppose antisemitic statements very energetically: they must see that those who challenge them have no fear.’ Or as my grandmother used to say, ‘Always answer a bigot – not to help them, but to show everyone around them who they are.’ Adorno: ‘If one engages without fear in such cases and answers these people’s arguments quite frankly, one can achieve something.’ Adorno calls this ‘shock therapy’ with ‘militant enlightenment’. If someone insists on national self-interest above all else, ‘They should be reminded of where it all leads, and what would most likely happen to them under a new regime of wholesale fascism or semi-fascism.’ And with this, we return to the question of nationalism. Adorno lays down his cards: ‘Effective prevention of antisemitism is inseparable from a prevention of nationalism in all its forms. One cannot be against antisemitism on the one hand while being a militant nationalist on the other.’ This would hold for nationalism of the Left as well as that of the Right. By ‘nationalism’ Adorno has in mind that governmental form that is based on exclusion and oppression of those who are not identical to the mythic perception of those who make up the nation-state in question. He does not simply mean nationalism understood as the right to self-determination – although there is perhaps a thinner line than most would like to imagine between the two (else why would the repressed antisemtic views in Germany constitute a problem?). Adorno is talking about militant, exclusionary nationalism.

In today’s context, the current American administration would clearly be a militant nationalism of the Right. Given the treatment of Palestinians in the West Bank by Netanyahu’s associates, Ben Gvir and Smotrich, it would seem that Israel’s current government is as well – I mention Israel because Adorno indicates that one ought not use Israel as part of an argument against antisemitic interlocutors. By the same token, I believe that Adorno would see particular violent incidents erupting on the Left under the banner of ‘Free Palestine’ as part of a nascent exclusionary nationalist movement of the Left. Adorno was extremely critical, for example, of the one-sided and reactive character of the student protests in Germany during the 1960s, and had little problem saying so. He was a man of the Left who was not dogmatically ‘leftist’.

Given that the United States is in the middle of a nationalist upheaval, Adorno would say that the time is unfortunately not conducive to fighting antisemitism. We see this not only in America in general, but also in American Jewish criticisms of Netanyahu’s handling of the war in Gaza. If Ehud Olmert is now considered a traitor by some American Jews, this – for Adorno – would amount to setting up the distinction between ‘good’ Jews and ‘bad’ Jews (the latter of whom need to be excluded from political analysis). This would be an internalisation of the same antisemitism that afflicted all Jews from the outside. On the other hand, this is part and parcel of being a nation-state, where exclusion is a perpetual possibility. Gordon gestures to something like this, in the Afterword, when he mentions about Israel’s ‘Faustian bargain’ in becoming a nation-state. Gordon presumably introduces Israel into the discussion similarly as a result of Adorno’s mention of it. For Adorno, whether – after Auschwitz – the State of Israel was a Faustian bargain or a compromise-formation borne of necessity remained a live question. We can at least acknowledge, with Gordon, that Israel (as a nation-state) is subject to the same militantly nationalistic tendencies that the United States, France, Germany, Iran, China and any other nation-state are.

In light of all this, I think we have to unfortunately acknowledge that – read in a straightforward manner – Adorno’s ‘today’ is not our own. In the United States, antisemitism is on full display. With the advent of social media, influencers are able to spout all manner of hatred with little to no consequence. Moreover, online editions of ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion’, ‘The Eternal Jew’ and the radio addresses of Charles Coughlin (for example) are available for free. This does not bode well for enlightenment discourse. In fact, the tenor of American antisemitism is perhaps better expressed by Jean-Paul Sartre in Anti-Semite and Jew:

Never believe that anti-Semites are completely unaware of the absurdity of their replies. They know that their remarks are frivolous, open to challenge. But they are amusing themselves, for it is their adversary who is obliged to use words responsibly, since he believes in words. The anti-Semites have the right to play. They even like to play with discourse for, by giving ridiculous reasons, they discredit the seriousness of their interlocutors. They delight in acting in bad faith, since they seek not to persuade by sound argument but to intimidate and disconcert.

Normally, one would look to the authorities (as Adorno suggested) to deal with such extreme antisemitism. But the current administration (with members who entertain ties with antisemitic and white nationalist organisations) appears to be using antisemitism as a pretext to reconfigure (or destroy) higher education and to deport immigrants (for example: the person lobbing Molotov cocktails at the group in Boulder sitting in vigil for the Israeli hostages is an Egyptian national – yet Egypt is not on the list of countries whose nationals are prohibited from visiting the United States). If Adorno’s suggestions seem ineffectual to us, it may be because we are not a country of repressed, ‘neurotic’, antisemites, but rather one inhabited by the wild ‘psychotic’ variety.

And yet, there is a way to read Adorno’s text that places his ‘today’ closer to ours. Given Adorno’s project of ‘negative dialectics’ – the expression of all normative statements about society in the negative in order to avoid subsumption by that society itself – we are justified in taking Adorno’s suggestions and programmes precisely as statements that show precisely how far away current society is (either in Germany in 1962 or the United States in 2025) from realising them. In Minima Moralia, Adorno asks ‘What would happiness be that was not measured by the immeasurable grief at what is?’ It would be wonderful if we could counter antisemitic stereotypes with rational discourse. It would similarly be wonderful if teachers had the resources to stand up to parents when the latter are wrong. That neither is the case shows exactly how far away society is from achieving enlightenment. This, for Adorno, is not a reason to despair. It is only through the recognition of our failure that we can learn what success would be. And thus, Adorno ends his lecture on a profoundly negative note (one that he will echo in his masterwork, Negative Dialectics): ‘Racial prejudice of every variety is archaic today, and in glaring contradiction to the reality in which we live . . . “Such a thing must never happen again.”’ – a plea that current humanity is still far from heading.