Marina Barats is a recent MA International Political Economy graduate from King’s College London

Background

President Joe Biden hoped to build on President Trump’s legacy by expanding the Abraham Accords to secure the ‘crown jewel’ of US foreign policy in the Middle East – normalisation between Israel and Saudi Arabia. Yet while the Israel-Hamas war halted the negotiations, and Saudi Arabia has been extremely critical of Israeli military operations, it seems normalisation remains on the table, even its pursuit is currently ‘toxic’ for Saudi Arabia, due to its reputation as the leader of the Muslim world and the animosity of its population towards Israel as the war in Gaza continues. Indeed, despite demands to suspend arms exports to Israel, calls for a two-state solution and recent accusations of Israeli ‘genocide’ in Gaza, Saudi Arabia has not responded with action. In fact, it was among the countries which blocked motions calling to cut ties with Israel and prevent it from receiving arms from nearby US bases at the joint OIC-Arab League summit in November 2023. Ultimately it seems the two nations’ shared economic and security concerns will persist beyond the conflict.

The recent election of Donald Trump fuelled speculations that a deal between Israel and Saudi Arabia may be back on the table, as the President-elect seeks to build on the Abraham Accords legacy of his first Administration. Even without normalisation, there is potential for greater economic and security cooperation between the Abraham Accords states, Israel and Saudi Arabia, which may be advanced with proactive leadership from the White House. Building on that, political normalisation and economic cooperation through a free trade agreement (FTA) between Israel and Saudi Arabia, driven by a combination of commercial and security factors, may act as a precursor to stable peace between the two states. Both countries have capacity to contribute to the other’s development and security goals. They have commercial incentives for cooperation and do not perceive each other as security threats because they have common enemies (radical Islamism, Iran and its proxies), common allies (the US) and an interest in regional stability. For these reasons, Saudi Arabia silently approved the Abraham Accords as the UAE and Bahrain could not have signed them without Saudi blessing. In the post-Abraham Accords world, Saudi-Israeli normalisation and economic cooperation would establish an economically interdependent ‘pro-US camp’ in the Middle East and ensure stability and security in the region without America’s direct involvement, opening a new chapter for the region.

This essay does not touch on the potential political challenges of Israeli-Saudi normalisation following the Israel-Hamas war and the formal Saudi demand that it should include a pathway to Palestinian statehood. Instead, it discusses both the opportunities for cooperation between Israel, Saudi Arabia and the Abraham Accords countries that may be achieved without formal Israeli-Saudi normalisation and those that may be unlocked through normalisation and trade liberalisation between the two states. Specifically, it estimates potential trade flow between Israel and Saudi Arabia, analyses whether the business community in both countries would be interested in the normalisation and identifies potential sectors for collaboration.

Regional infrastructure cooperation

The Abraham Accords presented a historic opportunity for the US to be ‘an anchor of regional stability in a new political-economic bargain’ akin to that ‘achieved in postwar Europe’, as Egel, Efron and Robinson point out, where participants were motivated by a shared understanding of benefits from cooperation. Like in Europe, facilitating regional cooperation and integration may require American political, financial, diplomatic and military support. The Biden Administration coordinated the Negev Forum with Abraham Accords signatories, Egypt and the US and the I2U2 forum between the US, UAE, Israel and India and established the $3bn Abraham Fund to advance projects for regional economic development. Irrespective of the progress of Saudi-Israeli normalisation, regional integration in the Middle East may be substantially advanced through common infrastructure projects and security initiatives.

In the infrastructure domain, Israel has partnered with the UAE to expand regional fibre-optic cable infrastructure through projects like the Trans Europe Asia System, which would also connect Israel with Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, at the 2023 G20 Summit, the US, UAE, Saudi Arabia, India and EU signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) to establish the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC). IMEC consists of several elements. Firstly, the maritime-overland network would connect Western Indian ports, such as Mumbai, to Saudi Dammam and UAE ports. Goods would be transported by rail via northern Saudi Arabia to Jordan and then to Israel via the Sheikh Hussein Bridge to Haifa Port – departing to Europe. The railway link would have a significant advantage over the current maritime route: the distance between the Haifa Port and Saudi Dammam Port is 2,000km, whereas a maritime route is 6,000km and requires payment for passage of the Suez Canal. Furthermore, the railway would provide an alternative route to the Strait of Hormuz and Bab El-Mandeb, controlled by Iran and its proxies. According to Israeli estimates, regional trade volume could increase 400 per cent as a result.

While the railway would take several years to complete, the land bridge connecting the Gulf and Israel could be put into operation sooner. Indeed, following Houthi attacks on commercial ships, Israeli start-up Trucknet partnered with Emirati, Bahraini and Egyptian companies to provide coordinated trucking services for transporting cargo from the UAE and Bahrain to Egypt and to Israeli ports, via Saudi Arabia and Jordan. However, currently, it is only available to the abovementioned providers. Compared to maritime transit from the UAE to Israel, the land bridge reduces cargo delivery time from two weeks to four days but is 15-20 per cent more expensive. Despite great potential, there are challenges in the implementation of such initiatives – regulatory barriers, driver change requirements and customs waiting times. Opening the land bridge to all operators would require the standardisation of truck regulations and mutual recognition of drivers’ licenses. Eventually, the land bridge will assist tourism, facilitating social connections and cultural exchange. Houthi-induced trade disruptions highlighted the necessity and substantial benefits of an overland trade network connecting Israel and the Gulf. Perhaps Saudi Arabia could permit Israeli transport on its ground just as it opened its airspace for Israeli airlines in 2020. Overall, not only are there currently many projects aimed at increasing regional economic integration, but there are also substantial opportunities for further cooperation.

Security cooperation

Israel, Saudi Arabia and the Abraham Accords states have aligned security interests and may benefit from bilateral as well as regional cybersecurity and defence cooperation. In 2022, Israel, Morocco, Bahrain and UAE participated in the first Regional Cyber-Summit. The following year, the four states and the US agreed to expand the Abraham Accords to include cybersecurity collaboration via ‘joint cybersecurity training activities and information-sharing… to increase collective cybersecurity and resilience’ against shared threats. After a major distributed denial-of-service cyberattack against the UAE was thwarted with Israel’s help, the two countries announced the Crystal Ball initiative for further ‘collaboration and knowledge-sharing’. In addition to joint cybersecurity exercises and strategy meetings, Abraham Accords nations have signed a series of bilateral cybersecurity deals. For instance, the Emirati EliteCISOs and Israel’s CyberTogether signed an MoU pledging to help fight cybercrime by cooperating on knowledge-sharing, training and workshops. Considering that, since 2022, 40 per cent of cyberattacks on Saudi Arabia have been successful, perhaps the largest being the 2012 Shamoon attack on Aramco, potentially perpetrated by Iran, Saudi Arabia would vastly benefit from cybersecurity cooperation with Israel, both bilateral and regional.

Defence collaboration with Israel may help the Gulf nations localise their military industries and reduce reliance on the West for security. The Abraham Accords is the foundation of the regional security architecture emerging in response to the Iranian threat. In 2022, 24 per cent of Israel’s defence exports went to Abraham Accords states, valued at approximately $3bn. Morocco and Bahrain have signed bilateral security cooperation agreements with Israel in the military-to-military, air defence, industrial and intelligence arenas, while Israel and the UAE have been jointly developing military technology. Considering the shared threats in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, defence cooperation may be extended to maritime security – in 2022, for the first time, Israel joined a US-led Middle East naval exercise alongside the Abraham Accords countries, Saudi Arabia and Oman.

The Abraham Accords have demonstrated an important role for the US as a mediator between Israel and the Arab states, owing to aligned strategic interests and security concerns. Via the Abraham Accords the UAE gained closer ties with the US and access to advanced American weapons, while Morocco gained US recognition of its sovereignty over Western Sahara. Similarly, Riyadh requested security guarantees and support for its defence and nuclear programme from Washington, sparking debate among American and Israeli policymakers.

Thus, interoperability between Israeli and Arab militaries may be increased through CENTCOM (US Central Command in the Middle East). Following the Abraham Accords Israel was transferred from EUCOM (US European Command) to CENTCOM, of which Saudi Arabia is also a part. Israeli and Saudi military chiefs have participated in meetings, joint exercises and conferences discussing regional cooperation. When Iran launched hundreds of drones and missiles at Israel in April 2024 and again in October 2024, CENTCOM was crucial in coordinating a robust regional response, as British, American and Jordanian air forces shot down Iranian munitions. Furthermore, during the April attack, Saudi Arabia and the UAE provided Israel with intelligence and radar tracking information via CENTCOM channels. This instance underscores the crucial role of the US as a mediator and a regional integrator and reveals the need for more sophisticated regional security architecture.

Following the US’ idea of fostering regional security cooperation in the form of ‘Middle Eastern NATO’ in 2018, which remains merely hypothetical owing to the Israel-Hamas war and the likely reluctance of the US Congress to give an Article-5 like security commitment, some are calling on the US to advance the Middle East Air Defence Alliance (MEAD) as an ‘integrated air and missile defence network’. This would involve information sharing and early warning systems, enabling effective coordination against threats via CENTCOM.

Saudi Arabia would greatly benefit from such an arrangement. Between 2018 and 2022, only 20 per cent of Houthi long-range drone attacks on Saudi hydrocarbon infrastructure were intercepted while, in 2021, half of short-range Houthi drone strikes hit targets, revealing weaknesses in Saudi Arabia’s air defence system – radar scarcity, their inability to detect low-altitude threats and vulnerability to drone swarm attacks. Saudi Arabia’s air defence is over reliant on systems like Skyguard and Shahine, which are designed to intercept aircrafts and struggle against drones and slower cruise missiles, prompting Saudi Arabia to request more Patriots from the US.

Furthermore, the proliferation of drone warfare raises long-term budgetary questions for Saudi Arabia: missile interceptors such as Patriot or THAAD which cost $2-3 million dollars apiece are often used to strike down $10,000 drones and low-cost ballistic missiles. Meanwhile, Israel’s short-range Iron Dome and medium and long-range David’s Sling and Arrow, which have been successfully intercepting Houthi, Hezbollah and Hamas threats, cost around $50,000, $1 million and $2.5 million per intercept respectively. The UAE and Bahrain are considering purchasing the Iron Dome, Arrow and Israel’s effective radar system Green Pine. Due to the mutual benefits outlined above, air defence cooperation will likely be supported by both states’ military establishments and political elites. It may be the first step towards a new regional security architecture involving Israel, Abraham Accords nations and Saudi Arabia – a new chapter for the Middle East.

Predicted trade flow between Israel and Saudi Arabia

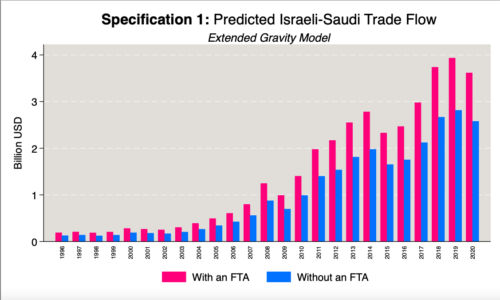

To estimate commercial benefits that may be generated through normalisation and trade liberalisation between Israel and Saudi Arabia, this research employs the gravity model of international trade to predict the likely trade flow between the two states in two scenarios – with an FTA and without an FTA. The latter describes a case where Israel and Saudi Arabia normalise political relations and trade on WTO Most-Favoured Nations (MFN) terms. To illustrate, before the Israel-UAE FTA entered into force on 1 April 2023, the countries had traded on MFN terms since the signing of the Abraham Accords on 15 September 2020. The gravity model expresses bilateral trade flow as a function of characteristics of the exporter-country (origin) and the importer-country (destination) and bilateral variables either impeding or boosting trade. It has demonstrated impressive empirical robustness. The gravity dataset was downloaded from CEPII website. The model consists of three specifications.

Specification 1 evaluates the relationship between bilateral trade flow and the distance between countries, their GDPs and other control variables including contiguity, social connectedness, religious commonality, common official language and a history of colonial relationship. The results demonstrate that having an FTA is associated with a 76 per cent higher bilateral trade, which is consistent with similar estimates in the literature. The predicted trade flow between Israel and Saudi Arabia is $2.7-2.9bn without an FTA, and $3.7-4bn with an FTA. These estimates are almost as high as the trade volume between Saudi Arabia and Turkey in 2021-2022 – $3.8-4.5bn – and are greater than the 2022 UAE-Israel trade flow of $2.5bn.

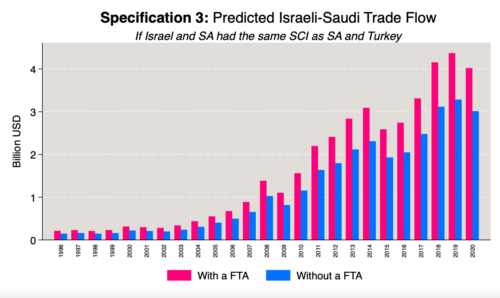

Specification 2 explores how social rapprochement due to normalisation can boost the gain from an FTA. Social connectedness index, a proxy for the level of social integration between two societies, measures the relative probability that two individuals in two countries are friends on Facebook. Results reveal that social connectedness and FTA are complementary in their impact on trade: the presence of an FTA enhances the effect of social connectedness on trade, and the gain from obtaining an FTA is greater when social connectedness is higher. When there is no FTA, a 1 per cent increase in social connectedness is associated with a 0.26 per cent increase in trade. Having an FTA increases the effect by a further 0.2 per cent. Therefore, when an FTA is present, a 1 per cent increase in social connectedness may bring a 0.46 per cent higher trade flow (see data appendix). These results support the argument that trade liberalisation helps advance people-to-people connections, while social and business networks facilitate trade.

As a result of growing business connections, tourism and cultural exchange and civil society programmes, social connectedness between Israel and Saudi Arabia may be increased substantially. In a rather optimistic scenario, Specification 3 shows that if Israel and Saudi Arabia had the same level of social connectedness as Saudi Arabia and Turkey, another Middle Eastern country that does not share a language or a border with Saudi Arabia, trade flow between them could increase by an extra $350 million, bringing the predicted trade flow to $3-3.2bn without an FTA and $4-4.3bn with an FTA.

The business community

Support from the Saudi and Israeli business community may help advance normalisation efforts. In Saudi Arabia, the line between political elites and the private sector is often blurred, and the economy is dominated by large companies dependent on the state for revenue and contracts. Political elites are often involved in business, and the state has controlling ownership of stocks in various public companies, often through the Public Investment Fund (PIF). State involvement in the economy is high: the ratio of private sector GDP to state expenditure is around 1.2-1.3, and the ratio of government to private consumption is three times the international average. Though business has more capacity for collective bargaining than most social groups, it tends to follow the government line on economic policy. Although there have been no official statements from Saudi business concerning potential normalisation, in 2023, Saudi officials announced that Saudi Arabia is interested in ‘integration, rather than mere normalisation, with Israel’.

Israel is a democracy and export-oriented economy, where the fastest-growing high-tech sector is almost entirely private. Israeli business has always pushed for normalisation with neighbours. The Israeli Export Institute and Israel-GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) Chamber of Commerce expressed excitement about commercial opportunities revealed by potential normalisation with Saudi Arabia, and the Chamber CEO noted ‘it’s the private sector, on both sides, pulling things forward rapidly’, adding ‘the transactions are between businesspeople… not between the two states’.

Sectoral analysis

Using the Atlas of Economic Complexity, which provides import-export data for 2021, and Vision 2030, Saudi Arabia’s strategy to reduce oil dependence, diversify income sources and facilitate innovation and investment, this research examines the composition of trade in Israel and Saudi Arabia and identifies potential sectors for cooperation. It proceeds to review the market landscape in these sectors to establish whether the business community is likely to support normalisation and an FTA.

ICT

Information and communication technology (ICT) is Israel’s main export, accounting for 44 per cent of total exports, while over 17 per cent of Saudi Arabia’s imports fall in this sector. Israel is a technological power with leading innovations in fintech, AI, cyber, cloud and other technology. A dynamic ICT sector is crucial for the digitalisation of Saudi Arabia, which is part of Vision 2030. Saudi Arabia aims to develop a vibrant digital economy, create a ‘digital government’ and localise and expand its IT sector.

The largest Saudi telecommunications companies include Saudi Telecom Company, Mobily and Zain KSA, SAP and Sahara Net. Besides telecom services, they provide digital services, payment services and cloud services and work on 5G, cybersecurity, AI and fintech. These companies are vital for Vision 2030, for instance, Zain and Enea cooperate on cybersecurity, and Mobily and Tencent Cloud collaboratively developed the ‘Go Saudi’ programme. Vision 2030 projects also include Neom, the $500bn ‘smart city’, the LINE and other futuristic developments Saudi Arabia may currently lack the technology for. Some factors indicate both Neom and Vision 2030 include Israel in their calculations – an investigation revealed Israeli-Saudi negotiations concerning Israeli companies doing business in Neom.

Energy, water and machinery

Crude oil and refined oil account for 40 per cent and 9.3 per cent of Saudi exports respectively and for approximately 2 per cent of total Israeli imports. Israel imports 99 per cent of its oil; its import is tariff-exempt. As of 2021, Israel imports 44 per cent of its crude oil from Azerbaijan, 25 per cent from the US, 9.6 per cent from Kazakhstan and less than 5 per cent from Nigeria and Angola each. Israel imports 54 per cent of its refined oil from India, 8 per cent from the US, 5 per cent from Italy and 4 per cent from Russia. The largest energy companies in Israel are Paz Oil Company, Delek Group, Sonol Israel, Dor Alon Energy, Bazan Group and Ten Petroleum Company. In 2021, the UAE began supplying crude oil to the Haifa and Ashdod refineries. Economic cooperation with Saudi Arabia would enable Israel to diversify its oil supply and reduce transport costs.

Saudi Arabia aims to reduce its reliance on petroleum, establish a competitive localised renewable energy (RE) sector and encourage private investment in it. Several Vision 2030 projects focus on renewables, particularly solar and water technology: King Salman Energy Park, Al-Khafji Desalination Plant and others. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman committed to achieving net zero by 2060 and generating 50 per cent of power from clean energy by 2030. The energy transition is guided by the National Energy Program; Saudi Power Procurement Company is responsible for the tendering process of 30 per cent of projects, and the remaining 70 per cent is allocated by PIF to ACWA Power. ACWA Power operates in water desalination and power generation sectors, leading most of Vision 2030’s RE programs. Companies including Saudi Aramco, Alfanar Projects, Abunayyan Holding, Al Jomaih Holding and Desert Technologies also participate in projects including the Saudi Green Initiative and Neom and emphasise innovation, knowledge sharing and collaboration with international partners in their business strategies.

Despite significant progress, Saudi Arabia is currently unlikely to meet its ambitious goals. Combined, the first five project rounds have achieved only 1 per cent out of the 50 per cent RE target, making the prospect of achieving it by 2030 improbable. Reasons for delay include human capital limitations and the difficulty of integrating Renewable Energy into the electrical grid. Access to Israeli technological innovation, knowledge sharing and exposure to new industrial practices may help overcome some challenges. Israeli solar industry is rapidly developing and innovating. For instance, Israeli companies have developed photovoltaics and vehicle-to-grid technologies and advanced renewable energy storage. Indeed, Israeli SolarEdge has already formed a joint venture with a Saudi firm to work on RE for Vision 2030.

Saudi Arabia imposes 5 per cent tariffs on imports of photovoltaic DC generators (global product Harmonised System (HS) classification code 85017) and other generating sets (HS85023); semiconductor devices, photosensitive semiconductor devices and photovoltaic cells are exempt (HS 85410). These products are vital for advancing the RE sector, which Saudi Arabia seeks to develop. Israel also possesses a rapidly growing water sector which uses some of the most efficient irrigation and desalination technologies in the world – the over-$2bn industry is considered among the main drivers of export-led growth. Furthermore, gas turbines, widely used in renewable power generation, and centrifuges, used in water desalination, account for 0.7 per cent of Israeli exports and 0.8 per cent of Saudi imports. Saudi Arabia imposes a 12 per cent tariff (5 per cent MFN) on irrigation systems (HS 84248) and 5 per cent on distilling or rectifying plants (HS 84194), gas turbines (HS 8411) and electrical and non-electrical machinery for filtering or purifying water for non-domestic use (HS 842121). Filtering and purifying machinery for liquids (HS 842120) and some centrifuges (HS 842119) are exempt. Evidently, establishing trade ties with Israel may aid Saudi Arabia in achieving its Renewable Energy ambitions.

Metals and chemicals

To diversify its economy, Saudi Arabia plans to expand metal production and mining. Unwrought aluminium, aluminium plates, flat-rolled iron and copper wire account for 1 per cent of Saudi exports. Exports of unwrought aluminium and aluminium plates have grown by 9.4 per cent. and 8 per cent respectively since 2006, and Saudi Arabia is increasing investment in the aluminium and steel industries as it intends to double its steel production and become one of the top aluminium producers. Israeli imports of these and other aluminium, steel and iron-based products are approximately 2.5 per cent. In Israel, imports of aluminium ores and concentrates (HS 2606), aluminium unwrought (HS 76011, 76012) and plated aluminium (HS 760611-760612; 760691-760692) are exempt from tariffs. Almost all types of iron and flat-rolled non-alloy steel (HS 7209-7212) are exempt too; the tariff on copper wires (HS 7408) is 2 per cent. Aluminium and steel are widely used in the construction, aerospace and defence, packaging, automative and electrical industries. 15 per cent of all unwrought aluminium imported by Israel in 2021 came from the UAE, and 2 per cent of aluminium plates came from Bahrain, so it is likely that normalisation with Saudi Arabia may facilitate trade in this sector.

Exports of polymers of ethylene, polymers of propylene and polyacetals amount to almost 7 per cent of Saudi exports; these products constitute 1 per cent of Israeli imports. Imports of ethylene polymers (HS 3901), propylene (HS 3902) and polyacetals (HS 3907) are exempt from tariffs. In 2021, Israel imported 9 per cent of polymers from propylene from the UAE and 5 per cent from Jordan, 8 per cent of polymers of ethylene from Jordan and 3 per cent from the UAE. These developments imply potential for trade between Israel and Saudi Arabia in the abovementioned industries.

Evaluation

In Saudi Arabia’s Renewable Energy and ICT sectors, the main players are medium-large companies, often partially owned by PIF, actively participating in Vision 2030 and associated projects. They invest in R&D and collaborate with companies in and out of the region, which indicates a lack of protectionist attitudes and a desire to integrate into the global economy. Generally, manufacturing and labour-intensive import-competing sectors tend to be the most protectionist, while tech sectors, including ICT and RE, benefit from foreign direct investment and technology transfers, which leads to innovation and growth. Business pragmatism therefore indicates a clear interest in supporting normalisation with Israel in these sectors.

On the Israeli side, most potential beneficiary import sectors are exempt from tariffs. Saudi Arabia imposes 5 per cent MFN tariff on most products used in the water and solar sectors. Currently, Saudi Arabia imports a substantial share of these products from the UAE, which faces equivalent tariffs on almost all product lines, despite customs union and Greater Arab Free Trade Area membership. This may be due to Saudi ambitions to localise RE value chains and develop manufacturing capacity. Therefore, it is unlikely that these tariffs would be dropped in an FTA, since Saudi Arabia aims to attract FDI, advance joint ventures and establish manufacturing on Saudi territory, rather than encourage the import of ready products from Israel. To illustrate, Saudi Arabia encourages companies to relocate their regional headquarters to Riyadh to secure government contracts and tax breaks. Therefore, Saudi-Israeli trade relations may be accompanied by technology transfers, learning by doing and exposure to better industrial practices, increasing productivity and building up Saudi industry in line with Vision 2030.

Regional economic integration

In a hypothetical research, Egel, Efron and Robinson model different scenarios of regional economic integration in the Middle East. A multilateral FTA involving five Abraham Accords signatories may create $73bn in new economic activity and 30,000 jobs for Israel and $75bn and 150,000 jobs for its partners over a decade. Within the GCC, tariffs are practically non-existent, and non-tariff barriers have been falling. Considering Israel already has an FTA with the UAE and, until October 7, was on track to sign trade agreements with Morocco and Bahrain, the idea of an Abraham Accords free trade area does not seem impossible. Researchers also modelled a multilateral FTA among the Abraham Accords nations and six more majority-Muslim states, including Saudi Arabia. It could create 4 million new jobs and $1 trillion in trade volume over a decade. For Saudi Arabia and Israel, projected new economic activity is $270bn and $260bn respectively, yielding 7 per cent and 13 per cent GDP growth and 192,000 and 107,000 new jobs. While merely hypothetical, it illustrates that an Abraham Accords signatories-Saudi Arabia free trade area could foster economic interdependence in the region, yielding trade benefits greater than the sum of its (bilateral) parts.

Conclusion

Observing the realisation of economic opportunities and mutually beneficial cooperation between Israel and the Abraham Accords nations, it is evident there is potential for regional collaboration involving these nations, as well as Saudi Arabia. Particularly in economic domain, through connectivity-enhancing infrastructure projects and a regional free trade area, and in the security sphere, in cybersecurity and air defence. Furthermore, there are hopes that normalisation and trade liberalisation via an FTA between Israel and Saudi Arabia, motivated by both commercial and security considerations, may provide a foundation for lasting peace and collaboration between the two states. Saudi-Israeli normalisation may generate $2.7-2.9bn, while an FTA would bring the trade flow to $3.7-4bn, and may increase with greater social and business connectivity. Gains from trade will likely be concentrated in the ICT, energy, water, machinery, chemicals and metals sectors, and the business community in both countries is likely to support the normalisation.