Ruth Ebenstein examines the vulnerability of Israel’s Bedouin community during the pandemic and explores both the self-help measures being taken by Bedouin NGOs and the creative solutions the community is seeking from the government.

As Israel rallies to battle the Corona virus, it seems that one group in particular lingers on the outskirts of the national mindset. Although the Health Ministry and experts have recently sounded the alarm and taken drastic steps to tackle the outbreak in the ultra-Orthodox population, which has significantly higher rates of Corona than the general population, and while testing has increased somewhat in the Arab sector, which was also initially overlooked, the Bedouin sector, with 220,000 residents living primarily in the Negev, has been largely left behind.[i]

Vulnerabilities

As yet, virtually no testing centres have been set up in Bedouin communities, despite the potential for an outbreak. While Rahat, the largest Bedouin city, did receive its first mobile Corona testing unit in early April and 450 people were tested in a matter of days, little has been done in the six recognised townships or in the 37 unrecognised villages in the triangular-shaped desert area in southern Israel, in which 100,000 residents live off the grid. As the stay-at-home rules and social distancing were taking hold in corners of Israel and consumers were stockpiling toilet paper, paper towels and hand sanitizer, Bedouins were largely left out of the national conversation. Schools and mosques did shutter their doors in Bedouin localities, yet a lack of access to technology and low digital literacy translated into limited exposure to the most basic information on the Corona pandemic that was broadcast on television and radio and saturated social media.

Many Bedouin residents, who don’t speak Hebrew and mistrust the government, are disconnected from Israeli society. While media campaigns were tailored to Haredi citizens in terms of tone and distribution and some efforts have been made towards Arab citizens of Israel, there has been no public awareness campaign specifically tailored to Bedouins thus far.

‘It’s almost if we are invisible,’ says Jamal Alkirnawi, a social worker born in Rahat, who founded and directs A New Dawn in the Negev, an NGO that provides programming for Bedouin youth-at-risk. When schools switched to distance learning in mid-March, Alkirnawi pivoted the organisation to address the pandemic. The organisation allocated its hotline, staffed by trained volunteers, to help the community get through the lockdown: secure the delivery of provisions, obtain their civil rights, and manage their stress. The NGO created an online platform to maintain contact between the organisation’s 1000-strong alumni from previous programs and disseminated a survey throughout the Bedouin population across the Negev to assess how it is coping.

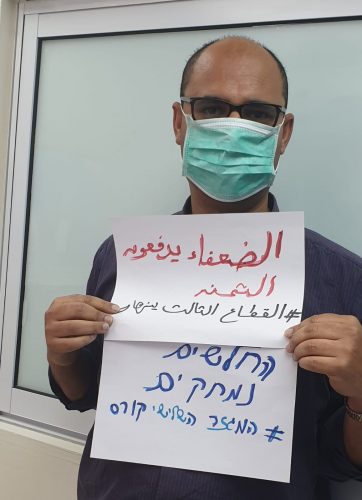

(Photo: Jamal Alkirnawi, founder and director of A New Dawn in the Negev. His sign reads “The Weak are Being Wiped Out: #ThirdSectorCrashing. Taken at New Dawn offices where he has been working 18-hour days to support the community. Photo courtesy of A New Dawn in the Negev.)

(Photo: Jamal Alkirnawi, founder and director of A New Dawn in the Negev. His sign reads “The Weak are Being Wiped Out: #ThirdSectorCrashing. Taken at New Dawn offices where he has been working 18-hour days to support the community. Photo courtesy of A New Dawn in the Negev.)

To sound the alarm about the dire need for action, Alkirnawi joined other NGOs, academics, social activists, communal leaders and lawyers in appealing to decision-makers to take steps to mitigate the spread of the pandemic. On 1 April, Adalah – the Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel filed a petition to the Supreme Court on behalf of a coalition of civil society organisations calling upon Israeli authorities to provide testing centres in proximity to Bedouin villages and bolster emergency ambulance services. ‘It became very clear to me that if we won’t be proactive about containing Corona in the Bedouin community, the consequences could be tragic’ Says Alkirnawi.

It is easy to understand his trepidation. The Bedouin sector is perhaps least equipped of all to fight COVID-19. In the unrecognised villages, residents live in prefabricated structures or shacks. These localities often lack infrastructure and basic services such as electricity, running water, sewage, garbage collection, paved roads, pharmacies and health-care clinics. Many do not have even a corner store to purchase groceries, or hand sanitizer. Some of the villages receive electricity through diesel-fuelled generators and have exposed sewage lines. For the vast majority, some 80,000 people, drinking water is provided by attaching a plastic hose to a water line of Mekorot, Israel’s national water company, or transported by tank to distribution points. The lack of a sanitation system makes Corona-style personal-hygiene ordinances that mandate scrupulously washing your hands with soap for twenty seconds extremely difficult. ‘Just uttering that request sounds laughable,’ said Meigl Alhawashla, 59, a member of the Regional Council for Unrecognised Villages in the Negev, a Bedouin political advocacy group.

(Meigl Alhawashla, member of the Regional Council for Unrecognized Villages, a Bedouin political advocacy group. Photo courtesy of author.)

(Meigl Alhawashla, member of the Regional Council for Unrecognized Villages, a Bedouin political advocacy group. Photo courtesy of author.)

Nor does the edict of social distancing mesh well with either the physical conditions of Bedouin homes or their social-organisational structures and kinship-based family fabric. On average, Bedouin family size numbers seven, double the size of the average Jewish family. Multiple generations live together in crowded conditions in one household. Grandparents either live with or adjacent to their children and grandchildren. Unrecognised villages constitute one hamula, one extended family, which makes it more difficult to keep a safe distance while sheltering at home. A 50- or 60-meter shack can house between seven to twelve people. There isn’t adequate room for quarantining. Even if an individual family member were to fall ill, it would be culturally unacceptable to send that family member away. Salame Alatrash, head of the Al-Kasom Regional Council, penned a call-to-action letter to Prime Minister Netanyahu in which he proposed that local schools could be converted into quarantine centers.

The Bedouin sector is ranked in the lowest socioeconomic cluster of society. Approximately 70 per cent live in poverty. Residents usually collect Bituach Leumi (National Insurance Institute of Israel) allowances in cash at the post office, but under the current stay-at-home edict, they cannot leave to collect their salaries and benefits. Because the localities are unrecognised, the residents do not have an address, so they cannot have money sent to them. In addition, many of the older residents are illiterate and cannot fill out forms without assistance. ‘I myself can’t figure out those forms on my phone,’ acknowledges Alhawashla. His grazing sheep can be heard bleating in the background.

Bedouins in unrecognised villages live in an ongoing state of insecurity. The failure to resolve this decades-long dispute over ownership means that home demolitions are not uncommon. Beyond the trauma of having a home demolished at any time is the fact that today it means even more people living even closer to each other. In late March, the Negev Coexistence Forum for Civil Equality, along with 22 other civil society organisations, appealed to Attorney General Mandelblit to stop demolishing homes and crops in Bedouin localities.

Unfortunately, those who are on the geographic and social periphery are also on the periphery when it comes to health services. Many Bedouins suffer from chronic health conditions like diabetes and asthma, which place them at higher risk of having more severe symptoms from COVID-19. Notably, more than 25 of the 37 unrecognised villages do not have primary health services in their localities. Rather, they have access to HMOs that operate with limited facilities. This population sector suffers from structural deficits in chronically underfunded medical care, leaving them poorly equipped to handle the outbreak. As health-care recipients, they have not enjoyed the kind of consistent quality health care over time that facilitates a reliable patient-provider relationship.

Even going to the doctor or to the store to procure supplies is no simple feat. There is virtually no public transportation in Bedouin settlements. Residents are dependent on family members with cars. With almost no access to the internet, telehealth services are not an option. And there is a need for more ambulances for Bedouin residents that could access the hard-to-reach roads in the South.

While the closure of schools was needed to stop the spread of the Coronavirus, it had grave consequences for Bedouin students and families. Across the Bedouin townships and unrecognised villages, some 78,000 students are enrolled in 140 schools and 24,000 children are enrolled in 640 preschools and kindergartens. (The Bedouin population is young; 60 per cent are under the age of 18.) The absence of computers and access to technology has also made it extremely difficult for many Bedouin students to engage in distance learning. When national online broadcasts are slated to continue after the Passover holiday, the question remains as to how many Bedouin students will be participating. These pupils are already at risk of attrition (what is called ‘dropping-out’ in the UK). The rates of Bedouin students that complete the Bagrut matriculation exams are the lowest in the country. In 2016, that figure was 32.7 per cent as compared to 63 per cent for the Jewish students and 50 per cent for Arab and Druze students. The rate of those attaining Bagrut for entrance to the university is even lower. Dropout rates are very high; in 2015, some 30 per cent of Bedouin 17-year-olds did not go to school.

There is concern that the Corona pandemic will lead to increased rates of attrition, closing the door to formal education. ‘We fear that students will be absorbed into their family’s business and won’t come back to the classroom,’ said Alkirnawi. Those who struggle at this time may opt to not return. Alkirnawi was among the lay leaders who sent letters to the Director General of the Ministry of Education, Mr. Samuel Abuhav, imploring that steps be taken to bolster distance learning in the Bedouin sector. Suggestions include small-group learning over the telephone, using cellphones as hot spots to connect to the internet, providing laptops and routers to students, and offering alternative programs for those who cannot do distance learning.

Shuttered schools have brought another risk: food insecurity. Some 76 per cent of students hail from families that live in poverty; many count on the free hot meals served at school to meet basic nutritional needs and feed their children. As Alkirnawi works on disseminating surveys about stress, he eyes hungry children wandering the streets, looking for distraction. ‘There is a real danger of malnutrition and hunger,’ he acknowledges with a sad sigh.

Solutions

Bedouin communal leaders, academics and activists collaborated on a plan of action with Dr. Dorit Efrat Treister, a faculty member at Ben Gurion University’s School of Management, who specialises in cross-cultural management and reducing aggression. ‘We understand tackling Corona isn’t only a medical problem. It’s also about behavioural change.’

The following measures were proposed to educate and build trust: Stop home demolitions and immediately implement a public awareness campaign on COVID-19 shared by trusted authorities and sources. Form a task force of lay leaders to disseminate recommended behaviour during the Corona virus pandemic. Establish a centre for the Bedouin population to give directives on dealing with Corona in Arabic in the Bedouin dialect as well as in sign language for the hearing-impaired. Use the muezzin’s platform to share information and post lampoons at mosques and corner stores as well as the communal councils. Go door-to-door to distribute soap, face masks, gloves, and hand sanitizer. Other measures include: connecting Bedouin families to the water supply; enabling house-to-house testing; affording Bedouin residents of unrecognised localities to secure addresses; and arranging for deliveries of food and medicine to the villages as well as internet access.

These measures would greatly help the Bedouin population, assures Alkirnawi. Yet he urges us to shift our focus to also consider the emotional and psychological implications of this pandemic on Bedouin life. For Bedouins, not touching and keeping a distance calls for casting aside cultural practices of intercommunal intimacy expressed through hugs, handshakes, and kisses, and precisely during this time when fear is amplified. Tactile communication is paramount in honorifics and respect towards one another. ‘How do you tell people who have been reared in a society where hugging and kissing are part of the honorific that they can’t touch their elders?’ What will be the emotional price of going through this trauma—isolation, loneliness, anxiety, and financial challenge—without those regular outlets for expressing love and respect?

‘This is Israel’s test,’ says Alhawashla. ‘Does it want to treat it citizens equally, or create a second-class and third-class status? Corona doesn’t distinguish between Jew and Arab, European origin or otherwise. Bedouin doctors and nurses are caring for everyone on the front lines, endangering themselves like all of the other medical professionals. Please care for us like they’re caring for you.’ Alkirnawi echoes this sentiment. ‘We are NGOs with meagre means, providing essential services that ought to be provided by the government. I myself feel a personal crisis: how can I support the thousands of people, physically and emotionally, crippled with fear and ignorance who need emotional sustenance and financial support more than ever? Decades of neglect are now coming to the fore, with catastrophic consequences. Without a swift and sweeping effort to help our population fight Corona and its concomitant effects, I worry that Bedouin society will collapse.’

Footnotes

[i] Of the approximately 220,000 Bedouins living in the Negev, some 100,000 live in ‘unrecognised villages’ on which land tenure is under dispute. As a result, they live off the grid, and municipal services are often lacking. The Bedouin are descended from formerly semi-nomadic tribes that have a range of cultural traditions that distinguish them from other Muslim Arab groups. Most Bedouin live in the Negev region of southern Israel, with a sizeable population in the Galilee in northern Israel. Rahat is the largest Bedouin city in the Southern District of Israel. In 2018 it had a population of 69,032, making it the largest Bedouin city in the world. Over the years the Israeli government has made attempts, unsuccessful so far, to resolve long-standing and complex land and housing issues affecting Bedouin communities in the Negev, known in local parlance as Naqab. Minister Benny Begin was appointed to lead a consultation process and presented a plan in 2013. Agreement was not reached, however, and the plan was shelved. Issues of ownership and construction and services remain mired in the decades-old controversy.