One of the best-known antisemitic slogans of the August 2017 ‘Unite the Right’ white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, has come to be ‘Jews will not replace us’. But this is not where the marchers’ anti-Jewish rhetoric ended. A Vox documentary about the event featured a neo-Nazi participant stating that the city was run ‘by Jewish communists and criminal n***ers’. It is understandable why so few paid attention to this claim. In an American context, the second part was an unsurprising expression of racism, and the first part sounded simply too bizarre. (Communists running a southern American city in 2017?) But if Paul Hanebrink’s new book is any indication, we’d do well to pay closer attention to this sentiment.

In Hanebrink’s telling, the Charlottesville white supremacist was referencing one of the most potent antisemitic myths of the 20th century: Judeo-Bolshevism, which holds that Communism was a Jewish conspiracy and Jews are responsible for its crimes. Born out of the fear of the Bolshevik threat following the 1917 Russian Revolution, the idea drove much anti-Jewish violence that sprang up in the revolution’s immediate wake (at least 100,000 Jews were murdered in pogroms during the 1918-1921 period), which grew into a full-fledged paranoid vision of barbaric ‘Asiatic’ Jewish hordes infected with the Bolshevik virus sweeping westward, destroying everything that Christian Europe stood for, including national sovereignty.

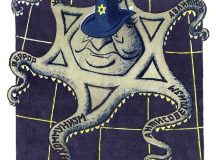

The idea became central to Nazi ideology. As Hanebrink puts it, ‘Judeo-Bolshevism made Adolf Hitler.’ So massive was the Judeo-Bolshevik monster that Nazi propaganda created that it made it easy for Nazi Germany to present the war on the Eastern Front as one of preventive self-defence. The imagery also merged seamlessly with pre-existing antisemitic views in the eastern territories that Germany sought to take over. From Lithuania to Ukraine to Bessarabia, the idea that Jews were communists and communists were Jews fuelled murderous pogroms, such as the Iasi pogrom in Romania and the Lviv pogrom in Ukraine in 1941. The idea also helped legitimise the organised mass murder of the Jews first by Einsatzgruppen (SS paramilitary death squads) and later in the death camps.

Given that millions of Jews were annihilated, in part, in the name of defending European civilisation and liberating Eastern European masses from Judeo-Bolshevism, it is natural to ask: how much truth was there to the idea? Was communism, in fact, a primarily Jewish enterprise? Was it actually something that Jews foisted on the unsuspecting Russians, Hungarians, and Romanians?

Hanebrink notes that in pre-war Poland, seven per cent of Polish Jews voted for the Communist Party, making Jews no more communist than Catholic Poles. Far more Belarussians and Ukrainians than Jews supported the Communist Party in the east and southeast of Poland (43 per cent and 46 per cent respectively). Political scientist Zvi Gitelman observed at a recent talk that whereas around a quarter of the pre–World War II Polish Communist Party members were of Jewish origin, those 12,000 to 15,000 Jewish communists were a drop in the bucket among 3.35 million Polish Jews.

To be sure, sums up Hanebrink, some Jews were communists, but the critical word here is ‘some’. Support for Communist parties throughout the region was consistently cross-ethnic. Far more Jews were engaged in Jewish politics (Zionism, Bundism, Yiddishism) than Communist parties, or were non-political at all. And vast sections of the Jewish community suffered massively as a result of the Bolshevik revolution.

And yet, the myth took, and it took ferociously, and no amount of evidence could convince its proponents to the contrary. Hanebrink recounts how in 1941, after the Romanian and German military recaptured territories that for a short spell had fallen under Soviet rule, the Romanian gendarmerie commissioned a study to determine how many Jews had served the Soviets. The report came back with extremely low numbers: in one county, only three of 128 local Soviet leaders had been Jewish. The provincial gendarmerie inspector ‘rejected the report as unacceptable and false’. He knew, he said, that all Jews were communists. ‘“The data,” he declared, “contradict the facts.”’

As with every case of anti-Jewish prejudice, believers in the Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy theory conflated individual cases with an entire people. The fact that Jews, previously unable to occupy positions of authority, were suddenly visible in positions of power shocked onlookers. And in a Europe where antisemitic conspiracy theories had already conditioned people to fear Jewish treachery, depravity and disloyalty; where belief in malicious Jewish plots to subvert and subjugate national cultures and politics ran rampant; and where the old order was crumbling under the weight of disintegrating empires, wars, and revolutions — the idea of Judeo-Bolshevik threat simply felt right. In the major cities of Central and Eastern Europe, including Vienna and Berlin, the presence of impoverished Jewish refugees — hundreds of thousands of those who had either been forcibly deported or were fleeing from the murderous violence at home — ‘proved’ their contemporaries’ fears true.

The defeat of Nazi Germany did not eliminate the myth. Neither did the post-war show trials and repressions against prominent Jewish communists, nor the massive state-driven anti-Zionist campaigns in the socialist bloc. With the fall of Communism, the myth re-emerged with new vigour as the newly independent states began to confront the world around them. Many in the region were shocked to discover that they were expected to join a European memory culture, where the transnational memory of the Holocaust had come to serve as a central unifying event and a source of universal moral lessons. Even more scandalous felt the idea that they had to examine their own role in the Holocaust. It was far more logical, they claimed, to have Jews apologise to them for the crimes of Communism.

Today, the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism is the unstated undercurrent of many Eastern and Central European right-wing governments’ attempts to shift the European memory culture away from its focus on Nazi crimes and the Holocaust toward Communist crimes. It lurks behind the ‘double-genocide’ theory that emerged from the region to suggest that the German genocide against the Jews is equal to the supposed Soviet genocide against these countries’ majority ethnic groups.

Not infrequently, the undercurrent bursts into the open. It did so, for example, in 2008 in Ukraine, when the country’s secret services published a list of 19 perpetrators of Holodomor (the artificial terror-famine of 1932–33). Canadian historian John-Paul Himka wrote that the compilers of the list made sure to underscore that eight of these were Jews by including their Jewish names in parentheses after their Slavic ones — a well-established practice in East European nationalist and antisemitic circles. Himka called this collection of names ‘an arbitrary and at the same time deliberate selection,’ noting that Holodomor had innumerable decision-makers and implementers at all levels of bureaucracy whose ethnicity would be impossible to sort out.

In another example, in January 2017, the vice speaker of the Russian State Duma implied, in a thinly veiled statement, that the grandchildren of the Jews who had come, wielding revolvers, out of the Pale of Settlement in 1917 were now continuing their grandfathers’ work of destroying Russian Orthodoxy. Now occupying influential positions in Russian politics and media, he suggested, they were preventing the transfer of a famous St. Petersburg cathedral (the issue of the day) to the Church. The statement reflected what historian Omer Bartov refers to as the Russian New Right view that Jews perpetrated a genocide against the Russian people in 1917, during Stalin’s terror and again under Yeltsin to gain economic, moral and political advantage.

And in Poland in February 2018, in the midst of a Polish-Israeli foreign relations crisis over the adoption of the so-called ‘Holocaust law,’ the right-wing Polish periodical Do Rzeczy published a cartoon showing a Pole kneeling on the floor, head lowered, as two figures in military uniform pointed pistols at him — a Nazi and a Bolshevik commissar with a red Star of David on his chest.

But as the Charlottesville march demonstrates, these sentiments are not confined to the region. Hanebrink observes that far-right movements and nationalists on both sides of the Atlantic have made the idea of Judeo-Bolshevism a prominent element of their worldview. One could easily pick up echoes of that ideology as Charlottesville marchers talked to Vox about a Bolshevik-style society in the US, the American state and media being aligned with the Jews to suppress ‘native-born’ white people’s freedoms, and about the need to fight degenerates, parasites, vermin and filth (all original Nazis epithets for Jews). The well-documented interactions of American white supremacists with their Ukrainian and Russian counterparts and other European far right extremists undoubtedly facilitate the transfer of these ideas.

Looking back over the bloody history of the Judeo-Bolshevik myth, it is shocking to realise how many deaths resulted from what essentially began as ‘fake news’ that no amount of ‘fact-checking’ could put to rest. (Among Hanebrink’s most heart-breaking stories is one about pre-war Jewish organisations’ futile efforts to explain the facts to the public and prove their communities’ loyalty to their countries of residence.) As for any antisemitic trope, the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism evolved again and again to speak to new generations’ predominant fears and driving new waves of paranoia and hate.

Hanebrink offers a richly textured account to illuminate how the myth evolved over time. He draws largely on examples from Romania, Hungary and Poland, and I found myself wishing that there would be as much detail on the Baltics and Ukraine. Doing so, of course, would have made the book impossibly long. Already for a casual reader, it may seem too dense with historical detail. But it is a well-structured narrative with a clear overarching argument. What the book makes exceedingly apparent is that without understanding the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism, we will not be able to fully grasp the philosophy and motivations driving the extraordinary rise of violent right-wing antisemitism today. It also demonstrates how the myth can be easily instrumentalised to apply to the ‘Muslim question’ and to challenge today’s liberal society, ideals of multicultural tolerance and human rights. All of this makes Hanebrink’s book exceptionally relevant.