Editorial Introduction: The controversy sparked by the publication of Word Crimes: Reclaiming The Language of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, the Summer 2019 issue of the academic journal Israel Studies, is now the subject of an extended exchange in Fathom. Cary Nelson’s review of Word Crimes has produced a sharp reply from Gershon Shafir. In turn, not only have Cary Nelson and Paula A. Treichler written a lengthy rejojnder to Shafir, but Ilan Troen, the co-editor of Israel Studies, and Donna Robinson Divine, a guest editor of the Word Crimes special, have each responded to Shafir’s critique. We hope Shafir will reply in turn and we invite other readers to continue this important discussion. The editors encourage future contributors to move the discussion on by directing their attention — critical or otherwise — to the substantive claims made in the essays that made up Word Crimes.

*

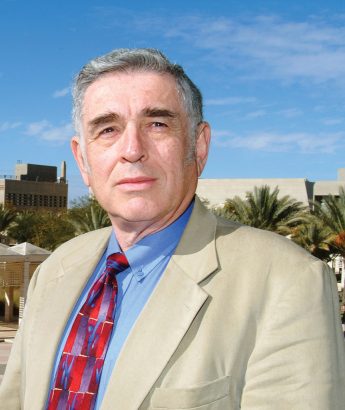

Ilan Troen is the co-editor of Israel Studies, the academic journal that recently published the controversial special issue Word Crimes: Reclaiming the Language of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. He argues in reply to Gershon Shafir that while it is right to be vigilant about academic freedom, Word Crimes was not a case of its suppression. ‘The scholars whose essays were published in the special issue were not advocating for Israel. They were not criminalising other scholars. They were writing critically about the discourse on Israel that they are engaged in and critiquing the language that impinges on the analysis of complex and conflicted questions.’

The recent special issue of Israel Studies entitled Word Crimes; Reclaiming the Language of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, has caused a stir that has yet to subside. Welcomed by many and viewed as scandalous by others, this is the only one of the 68 issues published by the journal over nearly a quarter of a century to become sensationalised, with criticism moved from the academy into the volatile public square. The vehemence of the dissent came as a surprise, although, in retrospect, it might have been anticipated. Israel has become a binary to be celebrated or castigated, often with extravagant emotion.

A fury accompanied the rejection of this special issue in petitions and letters posted on social media. This unprecedented public call for repudiation raises questions that call for analysis. The letter in Fathom from Gershon Shafir, an Israeli scholar long resident and working in San Diego, is a good place to begin. Shafir writes as an academic to condemn steps taken by a distant government. Specifically, he notes potential threats to Israeli higher education and culture such as the code of ethics for higher education that Asa Kasher promulgated under the aegis of former Minister of Education Naftali Bennett and attacks by former Minister of Culture and Sports Miri Regev on freedom of expression in cultural productions.

As Shafir’s repeated use of counterfactuals – ‘would have’ (but didn’t) – implies, these particular threats are now moot points. Every Israeli university senate has effectively quashed Kasher’s proposed code; Regev has recently been checked by the courts through a judgement that rejected a libel suit she brought against a news network for publishing embarrassing material on her behavior; and fortunately, Bennett is no longer in the government. Nevertheless, in Israel as in other states, academic and other freedoms cannot simply be taken for granted. Shafir is right to be concerned.

Yet Shafir’s alarm that Israel Studies, an independent academic journal published through Indiana University Press, reflects an extensive government-instigated conspiracy to stifle expression of dissent, is baseless.

There have been justifiable complaints about the structure of the special issue and its content. There is no basis for imagining the guest editors are less concerned with freedom of expression than Shafir. On the contrary, the special issue critiques language used to curtail free debate on Israel in the academy. It is this analysis that has earned it such widespread interest: Word Crimes has had an unprecedented second printing and an extraordinary surge in downloadings from the Indiana website. It has clearly struck a chord with many academics.

In his response, Shafir focuses on political threats to academic freedom in the Israeli ‘context,’ but entirely ignores efforts to stifle the expression of contrary views in the non-Israeli ‘context.’ Particularly in the US and the UK where, like Shafir, the guest editors and contributors to Word Crimes live and work, the discourse is replete with terms that encode political arguments in academic discourse and which are used to delegitimise Israel per se and marginalise those who support the Jewish state, however critical they may be of its shortcomings.

Shafir should know better. Verbal violence and political proposals that call out both academics and students for their relationship to Israel have been rife in the California system.

Nearly a quarter of the faculty in the US who have publicly supported BDS come from Shafir’s California. Of the 14 original founders of the US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (USACBI) – which coordinates academic BDS campaigns on US campuses – 13 are from faculty on University of California and California State University campuses. Not surprisingly, academic boycotters on California campuses were the first to attempt to implement the USACBI guidelines, which call for faculty to work toward shutting down their schools’ study abroad programmes in Israel. The senate of Pitzer College, a school within the Claremont Colleges, was the first to capitulate. Speakers on Israel and other Israel-related campus activities are frequently interrupted, and bias in curricula is rife in the state and subject to considerable public attention.

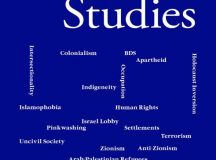

The editors of the special issue reject such abuses and in ‘Postscript: BDS’ argue that terms such as ‘apartheid’, ‘genocide’, ‘settler-colonialism’, ‘pinkwashing’ and others are ‘wielded by scholar activists’ with little or no actual knowledge of Israel and, moreover, that their use of these terms creates an atmosphere detrimental to dispassionate research and teaching.

In other words, Shafir’s complaint about repression is legitimate but too limited. The public assault on ‘word crimes’ is evidence that threats to academic freedom are widespread and come from many directions. So too, the positive response to the special issue indicates readers recognize the infection prevalent in major academic professional associations and in university culture generally, and that it merits attention.

Neither the editors and contributors to Word Crimes, nor their appreciative readers, should be assumed to be uncritical supporters of Israel. Manifest criticism can and does coexist with a repugnance at the campaign to deny Israel’s legitimacy. It is appropriate to object when scholarship bleeds into advocacy. The scholars whose essays were published in the special issue were not advocating for Israel. They were not criminalising other scholars. They were writing critically about the discourse on Israel that they are engaged in and critiquing the language that impinges on the analysis of complex and conflicted questions.

In the introduction, Donna Robinson Divine urges readers to think critically about how ideologies are encoded in the use of language. She does not argue that only the words included in the special issue are manipulated in this way. There is no monopoly on the abuse of language.

A more extensive lexicon and variety of perspectives invite further examination. Such topics will be taken up and the conversation continued in future issues of Israel Studies.

Comments are closed.