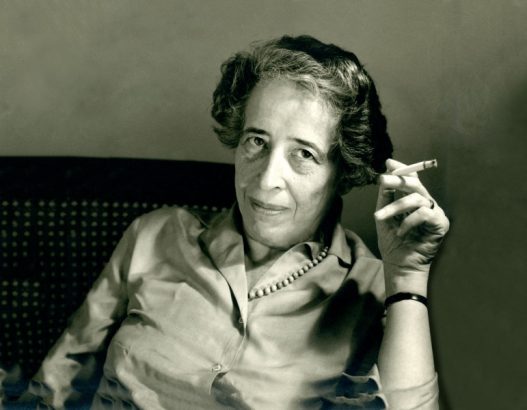

In this thought-provoking essay, Sarit Larry examines Israel’s discourse of ‘security’ through the prism of Hannah Arendt’s seminal essay ‘On Violence’. Israel’s focus on control of the means of violence, she argues, is inadequate. Israel needs a complementary model of security understood as the absence of conflict, or its diminished likelihood, once a shared public life dries up the ground on which conflict thrives. To use Arendt’s terms, true security demands power as well as violence. Download a PDF version here.

It is, I think, a rather sad reflection on the present state of political science that our language does not distinguish between such key terms as power, strength, force, might, authority, and, finally, violence – all of which refer to distinct phenomena. To use them as synonyms not only indicates a certain deafness to linguistic meanings, which would be serious enough, but has resulted in a kind of blindness with respect to the realities they correspond to … power and violence are opposites. Where one rules absolutely, the other is absent. – Hannah Arendt, On Violence, 1970.

I have led Israeli-Palestinian multicultural initiatives in Israel since 2013. My experience has left me feeling extremely hopeful and completely despairing at the same time. This essay examines that contradiction by tracing it to the pressure exerted by the dominant model of security in Israel, which views security as a function of the control of the means of violence. The more guns we have, goes this view, the safer we will be. I argue here for the value of an alternative model of security, understood as the absence of conflict or its diminished likelihood, once a shared public life dries up the ground on which conflict thrives. I base the distinction between these two models of security on Hannah Arendt’s description of power and violence in her seminal study On Violence.

My intent is not to suggest that the latter, ‘power-oriented’ model of security can simply displace the former, ‘violence-oriented’ model. Rather, I explore the potential for Israeli-Palestinian multicultural efforts in light of a possible synergy between the two.

Power vs. violence

Hannah Arendt claims that violence should not be understood as simply an extreme manifestation of power.[1] Rather, she treats violence and power as essentially distinct political phenomena, soliciting radically different kinds of obedience. Power should be understood as the rule of law, grounded in the consent of citizens and in historical legitimacy. This consent makes abiding by the law a matter of willful support, and so this support is ‘never unquestioning’.[2] This is fundamentally different from the unquestioning obedience, or rather submission, that violence tends to elicit. A woman obeying a robber pointing a gun at her, for example, is doing something fundamentally different than a woman abiding by the rule of law.

Politics, political institutions and the actions of the public authorities – what Arendt views as institutionalised power – rests on the tacit and/or articulated consent and support of the people. The state, in this model, is not an oppressive machine in the hands of the ruling class as Marx, for example, would have it.[3] Rather, it is a contract between a group of people to cohabit by rules that they see as good, or at least acceptable. Power is a human effort to establish the agreed dynamics of obedience and resistance between people. It is the essence of publicly shared human lives. The socio-political arena, Arendt argues, exists not only because we act in concert but so that we can act in concert.

Violence and power, according to Arendt, are not only different; they are opposites. Violence diminishes, disintegrates and destroys power. The quick and unquestioning obedience that violence elicits comes with a high price to the power applying it. For example, think of an armed police officer arresting a person in the street. In a place where power stands strong, it is the presence of a safe public space, structured by the support of bystanders, that allows her to make an arrest. She is acting within a power structure in which her role is legitimate and agreed upon. There is no need for her to use violence. If she does pull a gun at bystanders, and even worse, if she shoots at a bystander, the power around her might rapidly diminish. In the face of violence power is destroyed. If bystanders withdraw their support, then the police officer is likely to feel she is in danger even though she has a gun. Without power, violence is not as effective.

States, as structures of institutionalised power, use violence, of course, but Arendt warns us that if they are to retain popular support, their use must be seen as justified. The word ‘justification’ should be taken literally: the state use of violence is expected to be just. A government that uses unjustified live fire against its citizens risks losing that legitimacy. This is why governments seek to resolve domestic tensions and conflicts in ways that do not risk the very basis of power, which lies in consent.

Note that in Israel, refusing to serve in the IDF for moral reasons results most of the time in only symbolic punishments. This is because those who refuse almost always belong to a strong group in Israel and a full-blown use of violence by the state against this group would be self-destructive and highly dangerous. Violence against people of other states, however, is less risky. And that holds true for marginalised and weakened communities within the state. It is only a problem for a state to use violence if the broad mass of the people who uphold the power structure oppose it as unjust. For example, the state’s use of violence against Bedouins in Israel will only become a problem for the state if citizens beyond the Bedouin community withheld their support from the government in protest.

Two concepts of security: violence-oriented and power-oriented

Based on this distinction I want to suggest two corresponding models of security. The violence-oriented model argues that the more guns a state has, the more secure it will be. Security, in this perspective, is understood in terms of the command-obedience relationship. Pre-emptive strikes are conceived as a way of avoiding war and ensuring security. Violence against people is seen as a way to avoid more violence. War is understood as a way to ensure more security. If this model has a utopian vision, it is of perfect security achieved through the perfect weapon; ‘smart’ weapons, the ‘mother of all bombs’ etc. At its best this model thinks of violence as a last resort after diplomacy has failed. At its worse, it assumes all diplomacy is really a mild form of violence. At root, humanity is assumed to be essentially violent and efforts at non-violence to be fake or naïve.

By contrast the power-oriented model sees co-operative relationships as the basis for sustainable and non-volatile security. It assumes that people with mutual understanding are less likely to hurt each other because such people will develop shared goals and interests, among which avoiding a bloody interaction is central. Utopia, in this model, is a safer life in which people can prosper. It sees the hard work that facilitates spaces for inter-communal cooperation as ongoing, perhaps never-ending, and a goal in itself. The notion of a ‘once and for all’ solution is not central to the utopian vision of power-oriented security model. At its best, this model strives to invest in grassroots efforts of dialogue as well as macro-level arrangements (i.e. laws, treaties, national education plans, international agreements, unions etc.) since it believes that power has much to do with security and that power itself grows from pluralism, cooperation and equality. This plurality, the model tells us, needs to be sought, defended and nurtured. At its worst, the model assumes meaningful and active bonds will emerge between people spontaneously, even if they meet only once.

These two models of security interact in all socio-political arenas. But in Israel one of them has been so dominant for so long that the other is not considered a model of security at all. The next section of the paper explores the consequences of this imbalance.

Multiculturalism and the two concepts of security

In Israel, what we have called, using Arendt’s terms, ‘power-oriented security’ is rarely thought of as security. In fact, initiatives which are part of the power-oriented security model in Israel – peace movements, solidarity rallies, dialogue groups, multicultural gatherings, bilingual education – shy away from the word ‘security’. The word has become a synonym for what one finds within the violence-oriented model. And for this very reason, mere mention of ‘security’ in multicultural gatherings can erode trust and ties between people. Because the violence-oriented security model dominates the discourse of the Left and Right in Israel, it is usually taken as common sense that violence at an extraordinarily high level is frequently necessary, and therefore justified, while multicultural initiatives, since they are assumed to have nothing to do with security, can be side-lined at nil-cost, until the latest cycle of hostilities is over. Left-wing Jewish MKs tend to either support or remain silent when these ‘cycles’ commence; their ostensible commitments to agreement with Palestinians are put on hold, as if violence does not weaken and destroy the possibility of willful cooperation.

During multicultural events, the potential of the power-oriented security model becomes tangible to participants. The lived experience of face to face meetings for Palestinians and Jews – who, even if they are both citizens of Israel, rarely meet on a daily basis and effectively never meet in the educational system – can be revelatory, opening up new horizons and understandings, alleviating fear and hatred. Most participants are deeply moved at some point during these meetings. The hope they feel in such moments is neither naïve nor irrelevant to security, but is an intimation of the possibility of security based on power. When this hope fades – as it usually does, because the multicultural project is small-scale and short-lived, and because the world surrounding the encounter remains as it was, saturated by the violence-oriented model of security – participants can experience the come-down as nothing short of devastating.

What is to be done?

I have no easy answers. I hope to prompt creative thinking in Israeli civil society. I do however wish to suggest two directions.

First, multicultural efforts should think bigger.

The environment we operate in is destructive. We need to aim to change it. The hobby/summer camp status of these projects is condemning them to marginality. The multicultural perspective should demand it is given a national status in terms of scope and funding. If we cannot demand it now from the most right-wing government Israel has ever known, we should at least have a detailed vision of a nationwide plan that we regularly share and refine with partners, funders, MK’s and of course the program participants. Not doing so means we are not sowing seeds, we are building sandcastles next to the waves.

For example: meetings between Palestinians and Jews should happen regularly in the public education system, funded by The Education Ministry of Israel, and be understood as important for security. Furthermore, diverse schools should be our declared aim. National peace initiatives and ‘peace processes’ should include a multicultural committee of experts to plan bi-national multicultural projects as part of the state’s annual budget. Such projects are crucial for both the success of any Israeli-Palestinian agreement and security.

Second, we need to get beyond ‘they are over there and we are over here’.

The majority of the Jewish people attending multicultural efforts are partial to the two-state solution. (It is, to my mind, a reasonable solution although it is not my favorite.) The problem is that the discourse justifying the two-state solution is often (not always but too often) a mild branch of the violence-oriented discourse. Campaigns calling for the two state solution are many times grounded in fears of being ‘outnumbered’ or losing the Jewish identity. It is a discourse that is not shy to use fear to encourage necessary separation. It paints a bi-national state as a horror in which Jewish national identity could not possibly exist. In other words, it sees the Palestinians only as partners in terms of finalising the separation. Cultural familiarity and socio-political cooperation are not central. Fear is. Such an attitude is not helpful for power-oriented security. People who support the two-state solution should think again about this kind of discourse. Separation is not the goal; living together in a safe manner is. Without power-oriented security based on willful cooperation, consent and legitimacy, we will always be insecure.

[1] Arendt, On Violence. 35

[2] Arendt, On Violence. 41

[3] Arendt, On Violence. 37