Michael Herzog served as head of the IDF’s Strategic Planning Division and chief of staff to Israel’s minister of defence. In this in-depth essay Herzog examines Israel’s strategic interests and polices in light of the recent de-escalation agreement for the southern theatre in the Syrian civil war. Herzog argues that the West should utilise their existing military assets on the ground, as well as fostering cooperation with willing regional partners, in order to address the Iranian threat emerging in the post-ISIS region.

Introduction

A trilateral agreement announced on 7 July by the US, Russia and Jordan to turn the area of southern Syria bordering Israel and Jordan into a de-escalation zone highlighted the little-noticed fact that the situation on the ground had escalated considerably since the beginning of 2017. While most eyes were fixed on the developments in the northern parts of Syria, war has erupted and reached dangerous levels in the south of the country in Dar’a, the Yarmouk Basin, the Quneitra governorate, and al-Badiya in the south-east (for more details see the Appendix: ‘Background – escalation in southern Syria’ section of this paper). The southern Syrian arena has involved military actions by numerous actors – an array of rebel groups, jihadists, the Syrian army, Iran and its Shiite proxies, Russia, Jordan and Israel – facing one another in several sub-theatres.

This paper details the de-escalation agreement and analyses its potential significance for Syria’s neighbours Israel and Jordan, mapping their concerns against the background of conflicting interests and strategies pursued by various stakeholders. In particular, Israel’s public objection to this agreement sheds light on the broader context surrounding the situation in southern Syria, namely, the concern that Iran and its proxies might fill the void created by the upcoming defeat of ISIS and turn Syria into a permanent political, military and economic stronghold, threatening Israel and Jordan.

The de-escalation agreement and zone

The de-escalation agreement (titled the ‘Memorandum of Principle for De-escalation in Southern Syria’) has not been published and some of its details remain to be finalised. From what is known, it can be summarised as follows:

- Russia sponsored this agreement in the context of its general initiative to establish a number of de-escalation zones in Syria under the Russian-led Astana political process for Syria, which comprised Russia, Iran and Turkey, including such a zone in southern Syria (one of four intended zones)[1]. However, the current agreement was designed by Russia, the US and Jordan, since Jordan and Israel wanted to exclude Iran and Turkey and include the US.

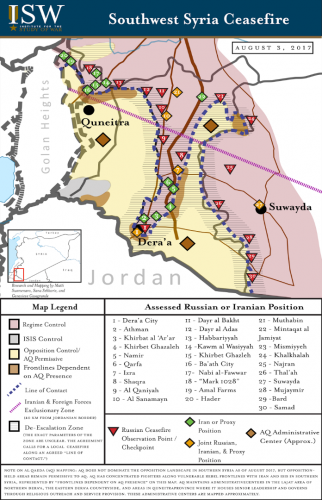

- The zone spans across the three southern governorates (from west to east): Quneitra, Dar’a and Sweida,’ encompassing over 10,000 km2. The agreement establishes a cessation of hostilities in these areas and sets the stage for the provision of humanitarian assistance and the return of refugees.

- Each of the parties will ensure that forces under its influence will abide by the terms of the agreement: Russia vis-à-vis the Syrian regime, Iran, and Iranian proxies; the US and Jordan vis-à-vis rebel forces supported by them. Excluded are the extreme Islamist elements on the ground; ISIS and al-Qaeda-affiliated groups.

- Russia agreed that all elements of ‘non-Syrian’ origin (implying Iranians, Hezbollah and other Shiite militias) will be distanced from the border area, however it is unclear how far away[2] and under what exact terms.

- According to Russian official statements, the US agreed to reaffirm the principle of Syria’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and implicitly accepted and legitimised Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s continued role as part of the political solution.

- The agreement will be monitored by Russian military police on the ground, as well as by a monitoring centre in Amman. On 18 July, Russian military police battalions were deployed inside the zone, establishing check points and observation posts together with the Syrian army, as close as eight miles from Israel’s border. In late August, the Amman Center for Ceasefire Control in Southern Syria (AMC) was launched.

- Israel is not a party to the agreement, but was consulted throughout the process. That it was negatively surprised by the concluded text indicates that this process of consultation was inadequate.

The agreement, which went into effect on 9 July, has generally held on the ground, though clashes between rebel groups and ISIS in the Yarmouk Basin erupted beginning the third week of August. Meanwhile, under the umbrella of the agreement, the Syrian army began symbolically demonstrating and practically asserting sovereignty in the south: Syrian units have shared positions with Russian units; the Syrian Chief of Staff General Ali Ayoub visited Syrian units in the area on 1 August, including in the outskirts of Quneitra near Israel’s border; and Syrian army units expanded their control along the Syria-Jordan border. In a watershed development, in the second week of August, the Syrian army assumed control of the important Nasib Crossing[3] on the border with Jordan, after more than two years of absence.

However, doubts abound about the agreement’s long-term viability as it excludes the salafi-jihadi groups, opens space for the Syrian regime’s – and potentially Iranian – ambitions in the south, and faces Israeli objections.

Israel’s interests and policies

Establishing and implementing ‘red lines’

Israel has been very careful not to be dragged into the war in Syria. At the same time, Israel defined and articulated a number of red lines, whose potential crossing would trigger Israeli military action in the Syrian theatre – and has repeatedly acted on them.

These red lines include the following:

Preventing and deterring cross-border terror attacks and firing into Israel’s territory. Israel has made it a point to respond to even unintended fire into its territory so as to remove the potential temptation to target Israel. It has also occasionally used these incidents to hit pro-Iranian/Syrian regime operational infrastructure close to its border.

Preventing the shipment of strategic tie-breaking weapon systems – such as accurate surface-to-surface rockets, sophisticated anti-ship and anti-aircraft missiles, and non-conventional capabilities – from/through Syria to Hezbollah in Lebanon, which could impact a future Israel-Hezbollah confrontation. Israel has never assumed specific responsibility for any of these attacks, yet did publically acknowledge that it had taken such action on numerous occasions.[4]

More recently, Israel has also aimed to prevent the establishment of an Iranian and Shiite stronghold in southern Syria. Israel has closely followed the developing intentions and plans by Iran and Hezbollah to establish an operational infrastructure in this area and to ultimately turn it into a military and terror front against Israel. In January 2015, an airstrike – reportedly Israeli – hit a convoy in southern Syria, killing an Iranian general and several Hezbollah operatives touring the south. Samir Quntar, a well-known Druze activist[5] who worked with Hezbollah and Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) to recruit Druze close to Israel’s border, was targeted in December 2015 in a strike attributed to Israel. In 2016-2017, Israel reportedly hit targets belonging to the pro-regime Golan Regiment[6] which was operating in the Quneitra governorate, including (in March 2017) one of their senior leaders, who was believed to espouse ties with the IRGC.

Liaisons with key international and regional stakeholders

Following Russia’s military deployment in Syria, Israel was quick to launch a close dialogue with the Russian leadership and to establish an effective de-confliction mechanism between the IDF and the Russian military in Syria. The Russians not only understand Israel’s red lines but have respected them, in almost all cases saying nothing following reported Israeli attacks in Syria.

In the region, the central stakeholder for Israel has been Jordan – a critically important neighbour sharing a border with both Syria and Israel. During war years in Syria, Israel and Jordan developed a close dialogue at the highest levels, as well as significant coordination over shared interests in Syria (see below).

Israel has also developed relations with some of the more moderate local rebel elements close to its border. A central theme in these relations, which are essentially civilian rather than military, has been the provision of humanitarian assistance and medical treatment to Syrians wounded in the fighting in southern Syria. The IDF recently released details of its Operation Good Neighbour, according to which some 4,000 Syrians (including 600 children) received medical treatment in Israel since the programme began.

Additionally, Israel encourages the UN Disengagement Observer Forces (UNDOF)[7] to redeploy into the buffer zone established in 1974 between Israel and Syria in the Golan Heights. These forces were negatively affected by the fighting in southern Syria in recent years, prompting some governments to withdraw their forces and drive UNDOF away from the buffer zone. UNDOF ultimately re-deployed in parts of northern and central Golan Heights, but not in the south where jihadists are dominant. In April 2017, an anonymous senior IDF officer disclosed that Israel was willing to provide guarantees to the security of the UN observers should they re-deploy and resume operations in the entirety of the buffer zone.

Placing the de-escalation agreement and Israel’s red lines in the broader context of emerging Iranian schemes in Syria

Israel’s strategic concerns intensified as the war on ISIS in Syria and Iraq moved towards the latter’s defeat. Over the past year, it became increasingly apparent that Iran and its axis stand to benefit by filling the void – ‘ISIS out, Iran in’ in the framing of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu – thereby enhancing their power projection closer to Israel. Israel’s Chief of Staff, Lt. Gen. Gadi Eisenkot, succinctly defined Israel’s strategic thinking by telling an Israeli parliamentary committee in early July that distancing Iran and reducing its influence over the immediate circle surrounding Israel is no less significant for Israel than the defeat of ISIS, possibly more.

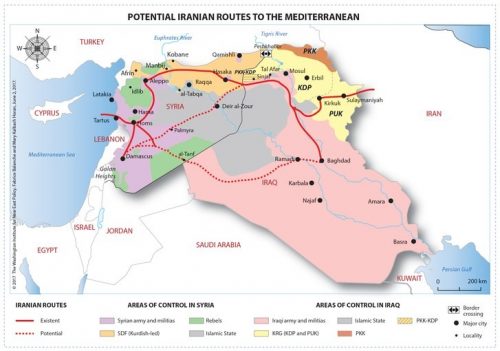

Iran’s design to create a land corridor stretching from Iran, through Iraq and Syria to Lebanon, is well under way and explains its focus on securing control of the border areas between these countries,[8] as well as the military focus and significant demographic changes along the way. In addition, Iran plans on long-term military deployment in Syria with permanent naval and air bases as well as a military industry, and (as was recently disclosed by Israel’s Director of Military Intelligence) on building underground factories in Lebanon to manufacture accurate rockets for Hezbollah. This all amounts to the creation of an Iranian sphere of direct influence in the heart of the Middle East – ‘the emergence of a radical Iranian empire’ in the language of Dr Henry Kissinger – spanning across Iraq and the Levant to the Mediterranean, with potential tentacles towards Shiite populated parts of the Gulf (in Bahrain, Kuwait and eastern Saudi Arabia) and southern Syria, facing Israel and Jordan.

The corridor would enable Iran to enhance its political, military and economic power in the region and to more effectively project it; by establishing its presence and infrastructure along the corridor; arming and empowering its proxies; moving forces and weapons across the region; and developing economic interests.

Iran could consolidate and control this corridor using essential assets at its disposal – its significant political, military and economic influence over the governments and territories of Lebanon and Iraq[9] and over the Syrian regime and army (who have become greatly dependent on it) in particular; and the tens of thousands of Shiite militias from across the region – even from Afghanistan and Pakistan – fighting under the command or guidance of the IRGC’s Quds Force in Iraq and Syria. Of these forces, most noteworthy is Hezbollah, which has become the most effective ground force in the pro-Assad coalition in Syria. Hezbollah possesses an arsenal of around 120,000 rockets in Lebanon aimed at Israel while holding veto power in the Lebanese government and maintaining close coordination with Lebanon’s president and the army[10].

From Israel’s perspective, this Iranian design is a major long-term strategic threat, as it would entrench Iran – a mortal enemy sworn to Israel’s destruction – in a neighbouring country, thereby increasing Iranian-Israeli friction and allowing Iran to turn regime-controlled Syria into a protectorate and its entire territory (not just the south) into an active front with Israel alongside Lebanon. Israeli planners now believe that in a future war with Hezbollah Israel would face the Syrian and Lebanese theatres as one, long, military and terror front guided by a unified logic combining plans, forces and capabilities such as rockets. There has already been talk in recent years of establishing a Syrian-Hezbollah, namely a permanent armed presence in Syria of a hybrid Shiite-Alawite force.

Under Iran’s current designs, the intended long-term presence in Syria of Lebanese Hezbollah and/or Syrian-Hezbollah is supposed to lean on Iranian permanent military presence in the country. Moreover, based on lessons learnt from recent wars in Syria and Iraq, this military logic may also include employing the ‘Shiite Legion’ against Israel in one or both theatres in times of active armed conflict. Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah has already threatened that in a future war he would open the borders of Lebanon to tens of thousands of fighters from Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and Iraq, while in March 2017 a Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU)-affiliated Iraqi Shiite militia – al-Nujaba (also known as Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba) – announced the creation of the ‘Golan Liberation Army’.[11]

Iran’s grand design challenges the above-mentioned Israeli red lines in Syria and Lebanon, posing serious dilemmas for Israel: If Iran crosses Israel’s red line by establishing a production facility for accurate rockets for Hezbollah in Lebanon and/or Syria, should Israel attack it and risk escalation with Hezbollah and Iran? Could Iran’s military presence in Syria against the background of Russian-brokered de-escalation arrangements limit Israel’s space for enforcing its red lines?

It is in this context that Prime Minister Netanyahu initially responded to the unveiling of the de-escalation agreement in southern Syria by stating on 9 July that Israel would follow developments in Syria according to its ‘red lines’. Yet Netanyahu added a new publicly-articulated red line of ‘preventing the consolidation of Iranian military presence in the whole of Syria’. This initial response was soon followed by an outright rejection of the agreement, in an unprecedented criticism of the US and Russia, highlighting the fact that the agreement fails to address Iran’s plans to establish itself militarily in Syria.

(Map: ‘The Race for Deir al-Zour Province,’ Fabrice Balanche, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 17 August 2017.)

Israel may have tested its newly-stretched red lines when, according to media reports and Syrian accusations, on 7 September it struck a facility belonging to Syria’s Scientific Studies and Research Center (CERS) in the Hama area in northern Syria. Whereas in the past Israel used to target convoys carrying strategic weapons for Hezbollah, this time it seems to have targeted a Syrian state facility producing accurate weapons for Hezbollah, (though the facility is known for producing chemical capabilities) with significant Iranian involvement, and in a northern area rather close to Russian deployment.

The role of the US and Russia

While Israel could take care of its own red lines in southern Syria, with implicit US support and Russian understanding, it feels that addressing the bigger Iranian challenge in Syria beyond the south requires a proactive American strategy. Unfortunately, it seems as if the US is narrowly focused on defeating ISIS and beyond that goal has acceded to a dominant Russian role in Syria and has implicitly accepted the al-Assad regime as part of a Russian-brokered political solution. Its recent decision to stop the programme of training and equipping rebel forces in Syria is a clear step in this direction, well noticed in Israel.

As for the Russians, whereas they have respected Israel’s red lines in southern Syria, it is unclear to what extent they will continue to respect them in southern Syria under the new agreement, whether and to what extent they will respect them in the rest of Syria, and whether they will be willing and able to enforce them on the Iranians and its proxies. These questions, especially the prospects of driving a wedge between Russia and Iran, also depend on the level of understanding and cooperation between the US and Russia, which is rather shaky. Israel was also unenthusiastic about the deployment of Russian military monitors in southern Syria, out of concern that this might limit its own freedom of action against emerging threats in the area.

To make Israel’s case regarding the strategic danger of Iran entrenching in Syria, a high level Israeli security delegation recently travelled to the US, followed by a meeting between Prime Minister Netanyahu and Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi. While Israel probably did not succeed in moving the US or Russia to proactively block Iran in Syria, the fact that Russia kept silent about Israel’s alleged targeting of the CERS facility in northern Syria may indicate that at least for the time being it is somewhat tolerant to Israel enforcing its expanded red lines beyond the south.

Israel’s specific concerns about the south

While the de-escalation agreement in the south currently converges with the Iranian-Syrian priorities in northern Syria, it clearly does not remove their ultimate ambitions in southern Syria. Their long-term goal remains regaining control over the border area and crossings for both symbolic and practical purposes; weakening, splitting and ultimately defeating the rebel groups; blocking the supply of weapons and other types of material support from Jordan; preventing the development of a threat on the capital city of Damascus from the south; and for Iran and Hezbollah – building a military front with Israel.

Seen from an Israeli perspective, the agreement (following the Russian position) essentially recognises the Syrian regime as the sovereign force in the south and therefore a part of the solution, while its coordination with the Russians on the ground provides it with favourable conditions to assert sovereignty in the area, as demonstrated by its takeover of the border crossing with Jordan. Since the agreement excludes the jihadi factions, the Syrian regime and affiliated elements could resume their military activities in the area and go beyond targeting jihadists, under the excuse of fighting terrorism and protecting Syrian sovereignty and its territorial integrity.[12] Ultimately, if the Syrian regime is empowered and rebel groups further weakened by the agreement, it could facilitate the gradual, below-the-radar development of the presence and infrastructure of Iran and its proxies in the south as well. And if war with Israel erupts, this would likely facilitate the rapid deployment of pro-Iranian forces in this region.

In any case, it is not clear under what terms non-Syrian elements and their operational infrastructure are dealt with within the framework of the agreement. Israel’s intelligence assesses that there are currently hundreds of Hezbollah activists in the area between Damascus and Quneitra, operating in cooperation with the Syrian army and the IRGC.[13] What will happen to them under the new de-escalation agreement?

As the full details of the agreement are still under discussion, Israel is closely consulting with the agreement’s three sponsors in order to insert its own interests into this process. The US and Russia responded to Israel’s criticism by publicly assuring Israel that its interests are taken into consideration. Alongside seeking translation of these assurances into the terms of the southern de-escalation, Israel attaches high importance to close coordination with Jordan. Among other considerations, Israel fears that an Iranian stronghold in Syria in general and in southern Syria in particular, may destabilise Jordan – an essential anchor of regional stability and a moderate, pro-Western neighbour at peace with Israel and sharing its longest border. While there is significant convergence of interests between Israel and Jordan on southern Syria, that convergence is not full.

Jordan’s interests and policies

Jordan has been very negatively impacted by the war in Syria. It lost an important conduit for external trade, over 50 per cent of which used to go through Syria.[14] It has also been flooded with waves of refugees to the point of hosting some 1.4m Syrians (close to 15 per cent of its population) who constitute a heavy burden on its fragile economy, infrastructure and social fabric.

The resurgence of jihadism in the region, first and foremost ISIS, has sent de-stabilising shock waves into Jordan, which has long been a hub for Salafism. Over 2,500 Jordanians joined jihadi groups in Syria and Iraq, and Jordan itself was subjected to numerous terror attacks, mostly directed or inspired by ISIS.

In late 2015, Jordan closed its 375 km-long border with Syria to refugees. As a result, a de-facto refugee camp numbering over 75,000 people was created on the Syrian side at Rukban, an arid remote area in the eastern tip of the Syrian-Jordanian border, close to the border with Iraq. The camp was infiltrated by ISIS activists and was struck by terror attacks a number of times. The most serious attack, in June 2016, killed six Jordanian soldiers and injured 14, and prompted Jordan to designate its eastern and northern borders as a closed military zone.

Jordan is therefore extremely sensitive about a jihadi presence along its border with Syria. In an interview to the Washington Post on 6 April 2017 Jordan’s King Abdullah II expressed concern that ISIS would move south following its upcoming defeat in northern Syria.

Jordan shares Israel’s concerns about the presence and power projection of Iran and its proxies in southern Syria. King Abdullah II, who years ago warned against a ‘Shiite Crescent,’ told the Washington Post that Iran has created ‘strategic problems’ in the Middle East and is attempting to ‘forge a geographic link between … Iraq, Syria and Hezbollah in Lebanon’. King Abdullah II highlighted the challenge of IRGC and Hezbollah deploying 43 miles from Jordan’s border, stating: ‘We were very explicit … that non-state actors coming towards our border are not going to be tolerated. I think we came to an understanding with the Russians.’

To better address these challenges, Jordan beefed up and upgraded its border protection, carried out military exercises facing the Syrian border[15] and launched occasional airstrikes against ISIS targets in southern Syria. More importantly, it developed close security coordination with Israel and became the key driving engine towards a de-escalation/ceasefire arrangement in southern Syria. From a Jordanian perspective, de-escalation in this area is essential to distancing both Sunni and Shia radical elements from its border and preventing further escalation, which could enhance the pressure of refugees and of terror attacks.

Jordanian and Israeli interests somewhat diverge regarding the role of the Syrian regime in the south. Israel regards the al-Assad regime as part and parcel of the Iranian axis, and believes that it will ultimately provide cover for its Iranian allies and their proxies if it were to take over the border area, as it already started doing. Jordan has vacillated in its attitude towards the regime, essentially moving from open opposition to active support for the rebel Southern Front (through the Military Operations Center [MOC] in Amman), through willingness to accept it in the south and have it resume control over the border crossings with Jordan, to welcoming the Syrian regime’s recent takeover of the Nasib Crossing and asking rebel groups under its influence not to oppose it. The reason for this change lies primarily with the impact of Russia’s military role, which tipped the balance in favour of the regime. This was followed by the belief in Amman that if the Syrian regime takes over the border crossings alongside a more general Russian-brokered de-escalation process in other parts of Syria, some essential trade through Syria could resume and the pressure of refugees could be mitigated. The Jordanian regime is not blind to the danger and does not trust the Syrian regime, yet seems to calculate that it is better to go for an imperfect agreement with American and Russian assurances regarding Iran, than be left with no agreement. From an Israeli perspective, however, the Syrian regime inevitably comes with some kind of an Iranian package.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the recently-concluded de-escalation agreement, the situation in southern Syria remains fragile and could deteriorate in the foreseeable future.

Above all, the US and its major European allies are well warranted to view de-escalation through the broader lens of the post-war regional strategic balance. They should pay careful attention to Israel and Jordan’s warning against Iran’s push to fill the post-ISIS void, which could further destabilise the region after years of wars and upheavals, including the threatening of stability in Western-aligned Sunni Arab states and the re-energising of jihadi elements. And they should design proper strategies to address this challenge.

In practical terms, the US and the UK should:

- Carefully examine if and how their existing military assets on the ground, which were originally deployed to fight ISIS, could be used to block Iran’s plans, rather than withdrawing them following the defeat of ISIS. For example, the deployment of Western and rebel forces in the Syria-Iraq-Jordan triangle (around al-Tanaf base), which stands in the way of the planned Iranian corridor, and air assets.

- Foster cooperation with willing regional partners who are likely concerned about Iran’s plans, including Jordan and Saudi Arabia. These partners could help develop cooperation with local Sunni tribes along the planned corridor.

- They could also use their relations with the Kurds in Syria and Iraq for the same purpose.

- Search for common ground with Russia in the context of curbing Iran’s ambitions in Syria. While Russia is unlikely to break away from Iran it could perhaps be persuaded in the service of its own interests to help limit Iran’s long-term plans for a permanent military presence in this theatre.

- Adopt a stated policy according to which any long-term political solution to Syria should include the evacuation of all non-Syrian militias and Iran’s military presence.

- Strive to translate the de-escalation agreement in the south, in agreement with Russia, to the distancing of the Iranians and their proxies to no less than 40 km from the border.

- Reconsider their intentions to stop backing moderate rebel groups in the south and the request that they withdraw to Jordan. Moving in this direction could push such groups into the arms of jihadi Hay’at Tahrir al-Sha’m (HTS – the Levant Liberation Committee – the up-to-date incarnation of al-Qaida-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra) in the south while playing into the hands of the Iran-Syria axis.

- Politically support Israel as it continues to carefully enforce its red lines in Syria.

It is not too late to develop a strategy for countering Iran in the post-ISIS era, thereby also providing a proper context for the de-escalation agreement in the south. Failing to do so, the tide of de-escalation could ultimately turn back into a major escalatory cycle.

[1] The Astana process produced an agreement (4 May 2017) to establish four such zones, one of them in the south of the country. Two more de-escalation zones were established as part of this process (through Egyptian mediation): one in northern Homs and one in the Eastern Ghouta suburb of Damascus.

[2] Reports range from 20 km to 40 km. In the northern part of the Golan Heights, where the Dar’a governorate is no longer to its east, the Qunietra governorate is narrower.

[3] The Nasib Crossing is an international border crossing along the Damascus-Amman highway, south of Dar’a, and served as the key trade conduit between the two countries. It was taken from the regime by rebel forces in April 2015.

[4] In an interview to Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz (25 August), the outgoing commander of Israel’s air force, Maj. Gen. Amir Eshel, disclosed that in the last five years the Israeli air force has attacked arms convoys and caches beyond its borders, mostly related to Hezbollah, nearly a hundred times.

[5] Quntar had served many years in Israeli jail for a heinous terror attack he perpetrated in Israel in the late 1970’s. He was released in a prisoner swap with Hezbollah.

[6] The Golan Regiment is comprised of former defectors from the Syrian army who (re)crossed the lines from the rebel to the regime side. It is part of the National Defense Forces (NDF) – an armed militia established by the Syrian regime. It operates mostly in the Quneitra governorate (as indicated by its name), from its headquarters in Khan Arnabah.

[7] UNDOF was established by UN Security Council Resolution 350 in May 1974, as a UN force designed to observe a buffer zone (Area of Separation) created between Israeli and Syrian military forces following the 1973 war, as well as additional areas with limitations on troops and weapons on both sides. The buffer zone is about 80 km long and between 0.5 and 10 km wide. UNDOF’s current personnel amount to nearly 1,000 people, mostly soldiers.

[8] These border areas include the Diala province bordering Iran in eastern Iraq; Tal Afar in western Iraq, where the Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU) have been fighting ISIS; the border areas between Syria and Iraq in both the north and the south east between al-Walid and Abu-Kamal (as elaborated in the Background); and the Qalamoun Mountains and A’rsal on the border between Syria and Lebanon.

[9] Iranian officials openly boast that Tehran controls four Middle Eastern capitals – Baghdad, Damascus, Beirut and Sana’a. Three of them are along the said corridor.

[10] Hezbollah’s now close relations with the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), to the point of coordinating anti-jihadi operations along the Lebanon-Syria borders, raise concerns in Israel about the erosion of the traditional non-political role of the LAF as a state organ.

[11] In late August, Iranian media outlets published photos of al-Nujaba militants deploying in southeast Syria.

[12] It should be noted that Israel does not believe that following the war, all of Syria can be put back together as a unified, stable political entity governed by a functioning central government. Since all options on the Syrian side of the Golan Heights look bleak (ISIS, Iran/Hezbollah, the Syrian regime) Israel approached the US with the request to consider recognising Israel’s 1981 annexation of the Israeli-controlled Golan Heights.

[13] According to Israeli information, IRGC elements are present in Jabah in the centre-north of the Golan Heights and were spotted in New Quneitra, very close to Israel’s border.

[14] Some of the alternative routes go through Israel.

[15] A big exercise, Eager Lion (May 1-18 2017) involving 24 nations headed by the US, was perceived by the Syrian regime as possible preparation for an invasion of Syria, and therefore sparked considerable tension between the two governments.

Appendix: Background – escalation in southern Syria

(Source: ‘Iran and Al Qaeda Exploit Syria Ceasefire,’ Institute for the Study of War, 3 August 2017.)

Dar’a: The southern Syrian city of Dar’a (where the Syrian civil war was sparked in 2011) and its surrounding governorate, has stayed relatively calm throughout the war. While the Syrian regime and its allies were preoccupied in the north, a coalition of approximately 50 rebel groups (to be known as the ‘Southern Front’) seized control of significant parts of the south, especially around Dar’a and towards the Israeli and Jordanian borders in southwest Syria. In early 2015, the Syrian regime and Iran amassed significant military forces (including Hezbollah and other Shiite militias) and launched a major offensive in the south with the aim of regaining control and reaching the borders with Jordan and Israel. The attack was by and large thwarted by rebel groups and the regime abandoned it for more pressing priorities.

Following their victory in Aleppo in December 2016, the emboldened Syrian regime and Iran once again fixed their sights on the south. The regime scaled up its political pressure on southern rebel groups in order to move them to its side (based on the post-Aleppo perception that the tide was turning in its favour), enhanced its presence in the area and prepared for another military push towards the border crossing with Jordan. Alarmed, local rebel groups joined hands and launched a surprise offensive on February 12, 2017 designed to push regime forces as far away as possible from the border with Jordan – their lifeline of support.

The offensive (titled ‘Death Rather than Humiliation’) united many rebel groups in the south, including Free Syria Army (FSA) elements and Islamists, first and foremost Hay’at Tahrir al-Sha’m (HTS – the Levant Liberation Committee – the up-to-date incarnation of al-Qaida-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra). It focused on the city of Dar’a, the control of which had been divided between the Syrian regime and the rebels, and specifically on the southern neighbourhood of al-Manshiye.

An important motivation driving the rebels’ offensive was the suspicion that Jordan prefers the Syrian regime resuming control over the border crossings between the two countries at their expense. Since the Russian deployment in Syria in late 2015, Jordan has conducted a dialogue and reached understandings with them about de-escalating the south, under which it agreed to restrain rebel groups from fighting regime forces and curbed support to them in return for Russia restraining the Syrian regime and its allies. The rebels, who trusted neither Russia nor the Syrian regime, felt they were in mortal danger.

As the rebels led by HTS succeeded in taking control over most of al-Manshiye neighbourhood, the Syrian regime and its Iranian allies launched a counter-offensive in Dar’a in early June, based on military reinforcements including from its elite 4th division (which is commanded by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s brother), Hezbollah combatants and Russian air support. This counter-offensive achieved little, yet prompted Jordan to exert greater efforts with Russia and the US towards establishing a de-escalation zone in the south, which ultimately yielded the above-mentioned agreement.

The Yarmouk basin: A second sub-theatre in southern Syria is the Yarmouk basin, situated in the border triangle between Syria, Jordan and Israel. A relatively strong presence of the Khalid ibn al-Walid Army[1] – considered the ISIS branch in southwestern Syria – developed in this area, with Israeli intelligence estimating their forces at approximately 1,000 combatants. On 19-20 February 2017 these forces seized the opportunity afforded by the above-mentioned battle in Dar’a and launched their own offensive, designed to expand their control in the Yarmouk basin. They managed to double their area of control, occupying a number of towns and villages (the biggest being Tasil, with a population of over 15,000 people) and enforcing in them an ISIS-fashioned code of conduct.

While this ISIS-affiliated group was primarily focused on confronting rebel or regime forces rather than Israel or Jordan, occasional clashes with these neighbouring countries did occur, especially with Jordan. Highly concerned about the growing ISIS presence as close as 1 km from its border and of occasional cross-border ISIS-initiated terror attacks, Jordan has carried out a number of air strikes against Khalid ibn al-Walid targets in the Yarmouk basin in recent months. Despite sustaining attacks by rebel forces, as well as some Jordanian and Israeli strikes and three times losing its top leader in the course of several weeks[2], the Khalid ibn al-Walid Army has managed to secure most of its gains since February.

The Quneitra governorate: A third sub-theatre is located in the Quneitra governorate west of Dar’a and close to the border with Israel. Most of western Quneitra (including the Quneitra crossing in the central Golan Heights) has been under rebel control for a number of years with other parts controlled by the regime and occasional clashes erupting between the two in the area’s northern[3] and central sectors. In late June, HTS and other local forces attacked the regime-controlled Madinat al-Ba’ath (New Quneitra), adjacent to Israel’s border. The exchange of fire repeatedly leaked into Israel’s territory, prompting Israel to strike some Syrian army targets.

Sweida’: The last southern governorate covered by the de-escalation agreement is Sweida’. Lying to the east of Dar’a and inhabited by a large Druze community, this governorate has remained by and large under the Syrian regime’s control/influence and has maintained relatively quiet throughout the war, with insignificant manifestations of protest towards the regime. Immediately following the de-escalation agreement in the south, the Syrian army and its allies in Sweida’ carried a swift offensive towards the Jordanian border, recapturing all the border observation points.

SOUTHEAST SYRIA

Al-Badiya: Further east, outside the southern zone of de-escalation, lies the desert area of al-Badiya (desert in Arabic) in the southeast Syria, which stretches northeast towards the Iraqi border. While developments in this area have been dictated by a different context, they have still impacted Jordan and Israel.

The area includes the US-controlled al-Tanaf base close to the al-Walid/Tanaf border crossing with Iraq. This military stronghold was established in the context of the US-led coalition’s war on ISIS in the east and north of Syria. It hosts some 150 US special forces alongside rebel forces such as the Revolutionary Commando Army as well as UK forces and other elements. A smaller stronghold, the al-Zakaf base about 70 km northeast of al-Tanaf, was established in June 2017 but evacuated in early September, probably based on US-Russia understandings.

As ISIS came under increasing pressure in the north, al-Tanaf came to face challenges from both ISIS and the Syrian army and its Shiite allies. On 18 May 2017 US planes bombed a convoy of Syrian regime and allied forces making its way in the direction of al-Tanaf, and in early June intercepted a drone in the area. Following these incidents, the US established a 55 km ‘safe zone’ around al-Tanaf, warning the Syrian army and its allies against entering it, and deploying a High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) in the area.

The Syrian regime and Iran were probably motivated by the concern that the US-led coalition might use al-Tanaf as a staging ground to push north and east and block their own drive to regain control over eastern Syria, including the essential areas of Deir al-Zor, the Euphrates valley and the border area with Iraq (in and around Abu-Kamal) which is still controlled by ISIS. This drive also constitutes part of Iran’s masterplan to establish a territorial corridor through Iraq and Syria to Lebanon in which eastern Syria forms an important part.

Given US warnings not to approach al-Tanaf, the Syrian regime forces and their allies pushed towards the Iraqi border north of al-Tanaf (though still inside the US-declared ‘safe zone’), and reached the border on 18 June where, for the first time in years, they met Iraqi Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU) – Shiite forces affiliated with Iran – coming from the Iraqi side. The Syrian forces subsequently expanded their control over a stretch of land along the Syria-Iraq border. These developments exemplify the Iranian ambition to fill the void created by ISIS’s collapse and were well noticed in Israel and Jordan.

The Iranian media speaks openly about the desire to evict the presence of the US and its allies from the al-Tanaf area, since they stand in the way of Iranian plans. While the US plans for the post-ISIS era are not fully clear, the signs are troubling. In early September, two Western-backed rebel groups fighting the Syrian army and its allies in southeastern Syria were asked by the US and Jordan to pull out of the area and retreat into Jordan.

[1] Khalid ibn al-Walid Army – Jaish Khalid ibn al-Walid – was born of the merger, in June 2016, of three salafi organizations operating in the Yarmuk basin area: Liwa’ Shuhada’ al-Yarmuk (the Yarmuk Martyrs’ Brigade), Harakat al-Muthana and Jama’at al-Mujahidin.

[2] Muhammad al-Maqdisi was killed by an air strike (likely Jordanian) in early June. He was replaced by Muhammad Rif’at al-Rifa’i (Abu Hashem) who was then killed in late June in the battle around the town of Hayt. His successor, Wa’el Faour al-‘Id (Abu Taim Inkhil), was killed in mid-August by an unidentified airstrike.

[3] In the northern sector there were repeated clashes around the Druze village of al-Hadr. The village remained under regime control and was attacked several times by rebel forces.

Comments are closed.