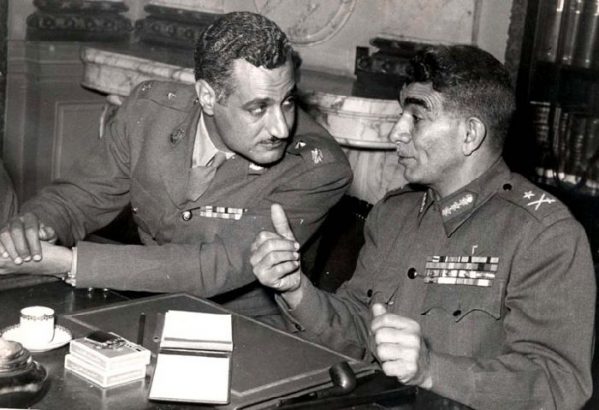

For 50 years historians have debated the question of what motivated Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s disastrous drift towards a humiliating defeat in the Six-Day War with Israel in 1967. Gabriel Glickman argues that the archives suggest we have underestimated the pivotal role of Nasser’s vendetta against America in driving Nasser’s actions. Current American and Israeli officials, he advises, should take note of this episode as a lesson in how history can play out when the US tries and fails to turn a formidable foe into a friend. With US policy now tilting towards the Sunni states and an angry Iran possibly left out in the cold, Glickman’s essay has more than historical interest.

Decisions leading to war are rarely understood without the benefit of documentation to show exactly what officials were thinking. However, in the case of the Six-Day War, historians have overlooked what has long been staring them in the face: Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser mobilised his army against Israel in mid-May 1967 in part to get back at the US for refusing to provide economic aid that the Egyptian leader so badly needed after years of wasteful spending on ‘Egypt’s Vietnam’ in Yemen. Not only does this challenge the conventional notion that Nasser acted to stop an alleged Israeli plan to topple the radical Baath regime in Syria, it demonstrates the limits of a US foreign policy that relies on appeasement to turn adversaries into friends.

To begin with, US President John F. Kennedy’s officials dealing with the Middle East believed that a close personal relationship between the president and Nasser, and generous amounts of economic aid without attached strings, could buy the Egyptian leader’s loyalty. However, in spite of an unprecedented three-year credit agreement, Nasser refused to disengage from Yemen, where he was locked in a proxy war against Saudi Arabia for regional mastery. Unlike his predecessor, however, Lyndon B. Johnson (who took office at the end of 1963) had little regard for ‘personal diplomacy’. If Nasser wanted to continue receiving American economic aid, he needed to withdraw from Yemen. Thus, when Nasser still failed to make progress on Yemen even after receiving a new six month credit agreement following the expiration of the original one, Johnson and Secretary of State Dean Rusk hesitated through the end of 1966 and the beginning of 1967 to approve Nasser’s request for more aid. Evidently, Nasser resented being made to wait. He considered the delay an indication of American imperial pressure and readily turned to the very issue that US officials had sought to circumvent through years of aid: Arab liberation of Palestine.

Thus, in a 22 February speech, the Egyptian leader established a connection between America’s supposed over-handedness in the Middle East and the issue of Palestine, essentially channelling for the first time what was to be the basis of his call for a war against Israel just three months later. He described to his Arab audience the cornerstone of an American plot to control Egypt through economic pressure:

The Americans get angry if they are attacked and want to silence us. They threatened us but we were not intimidated by their threats. We went along our path and America stopped all aid to us including, principally, her supply of £60 million worth of wheat. If we kept silent in return for this wheat, the Americans would take us by the scruff of our necks and never let us go.[1]

Nasser identified the US as a belligerent empire that was out for domination over the Middle East, thus making it clear that he was the last line of defence against its imperial machinations. In reality, he was resorting to demagoguery in order to prepare Egypt for the realities of its imminent economic crisis. What he said was:

… we could not submit to economic pressure or threats, because by refusing to submit we should be defending the Arab revolution, the Arab struggle, Arab sovereignty and Arab nationalism … Let me tell you that we are a hundred per cent independent country and we are ready to sacrifice £60 million [amount of forgone American assistance]. I knew that we should be in difficulties … But I was sure that every inhabitant of this country, if he had to choose between submitting to the Americans and receiving no aid, would say: ‘We won’t have the aid.’[2]

The crux of Nasser’s speech was that the US was on political manoeuvres in the region with the aim of undermining the stability of ‘revolutionary governments’ like Cairo.[3] As noted by a British official: ‘The predominant thought in Nasser’s mind when he made this speech was to make sure his people laid the blame for their privations at the door of the United States.’[4] Likewise, another British official observed that Nasser’s actions were an indication ‘that [Egypt] … wants to step up her hostility to the “traditionalist” Arab governments and to the Western world’. He also noted that Nasser was ‘assuming that they would get no further American aid’.[5] In short, the state of Egypt’s economy and the threat to American aid was driving Nasser into a conflict with the superpower.

Further deflecting from the dismal performance of Egypt’s economy, Nasser highlighted all of the positive work he had done to prepare the Arab world for an invasion of Israel:

Two years after the secession the requirements of Arab struggle made some kind of unity essential. In December 1963 I called for unified Arab action. On behalf of Palestine, and for the convening of the Summit Conference … If you remember, in 1963 I said that while certain Arab countries talked about Israel and the recovery of Palestine, in their secret councils they admitted that they were incapable of defending their existence on their own. We therefore had to meet at an Arab Summit Conference to discuss means of ensuring the defence of the whole Arab homeland, and then work for the restoration of Palestine to its people.[6]

Nasser then announced a ‘new stage’ in the Arab struggle against Israel:

We are only at the beginning and there are still many obstacles ahead, but this [Arab unity] is the only true formula and it is essential for the confrontation of imperialism and Israel.[7]

Nasser presented himself as having a selfless interest in liberating Palestine, unlike ‘America’s constant attempts to liquidate the Palestine problem and the Palestinian people’.[8] Therefore, just as in 1956, when Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal in a grand gesture of Egyptian triumph over the West after American funding for the Aswan Dam was revoked, he appeared to be getting ready to make another grand move that would revitalise the prospects of his regime.

Nasser tightens his grip in Egypt

In the absence of American aid, Nasser began to undertake a massive restructuring of Egypt’s economy that began to make his regime look more like a socialist dictatorship than the popular revolutionary government he had promised when he came to power in the 1950s. First, a Supreme Control Committee was established with a purpose ‘to keep a watch on the counter-revolution everywhere’.[9] The committee’s mandate was to make public sector companies more efficient. Draconian measures were implemented which included massive layoffs, a lowering of salaries, mandatory reviews for board chairmen over the age of 65, and a complete overhaul in production management that required business leaders to conduct themselves as ‘political leaders’ with the power to get rid of workers who were found to have ‘deviated’ and thus negatively impacted the company’s production quota.[10]

At the same time as the restructuring of public sector companies, the Arab Socialist Union (ASU) was also restructured to increase its influence in the state.[11] According to Nasser’s appointed head of the ASU, Ali Sabri, the guiding philosophy for the union’s activities should be based in large part on the ‘revolutionary thought of the leader of the revolution’,[12] the understanding being that Nasser was in charge of the ASU and that governmental checks and balances were illusionary. Moreover, since Nasser was in charge of appointments to the ASU’s Central Committee, it undoubtedly served as an extension of his will.[13] According to Sabri, the ASU had contacts with every echelon of Egyptian society and was therefore tasked with planning and implementing policies before measures were even brought before the parliamentary body known as the National Assembly. That legislative body was important in its own right, claimed Sabri, yet it was being relegated to a lesser role in favour of the newly augmented ASU.[14]

Nasser was creating a thinly veiled dictatorship. He was hardly ‘clueless’ in 1967 or a mere casual observer of political events, as recently suggested by one scholar.[15] However, such heavy-handed policies could do little to significantly fix the ailing economy in a short period of time. Moreover, the Egyptian public was becoming critical of the public sector companies and the chairmen of the boards were, in return, more critical of Nasser’s new policies.[16] What Nasser needed was a distraction.

The distraction

A farewell meeting with American Ambassador Lucius Battle, during which Nasser rejected the possibility of any future aid negotiations, became a convenient launching pad for a renewed propaganda campaign against the US Nasser’s mouthpiece at al-Ahram, Mohamed Heikal, released a series of eight articles that critically examined American policy towards Egypt. Using the metaphor of a ‘spider’s cobweb’ to describe American involvement in Arab affairs, it was claimed that ‘the cobweb’s threads were cut off’ when Nasser rejected American aid in his farewell meeting with Battle.[17] On 17 March, al-Ahram displayed the full text of Nasser’s rejection of American aid:

[W]hile appreciating and thanking you for all the facilities accorded to us in the wheat question, we want nothing now. In February 1966, we requested you to supply us with wheat. Since then we have neither renewed the request nor reminded you of it … We have been very patient with all the pressure you have applied to us because of the wheat, but our patience has run out. Please know that the value of this country and of its struggle lies basically in its capacity in all conditions to withstand all sorts of pressure – economic, military, or psychological.[18]

Nasser was using an anti-American campaign to bolster his political standing. The next day, the Arab League Council approved a resolution which condemned ‘the hostile attitude adopted by the United States to the Palestine problem,’ and asserted that ‘the United States has no right to interfere in the affairs of the Palestinian people’.[19] Nasser was exerting his control over the council in order to make trouble for the US in the Middle East, which he was doing by drawing attention to the superpower within the context of the proverbial Arab struggle for Palestine.

In the month of April, Heikal’s articles in al-Ahram continued to discuss the evils of American foreign policy, while Egypt’s ‘Foreign Relations Committee’ met to discuss Israeli aggression towards Syria and problems in American-Egyptian relations.[20] Nasser also continued to lay ground for a ‘new stage’ of Arab unity against Israel by sending his prime minister to Syria to discuss the two countries’ joint defence agreement, after Israel downed six Syrian jets in an air battle on 7 April. A joint Syrian-Egyptian communique declared, ‘The statements of the American and Zionist authorities have disclosed that the arming of Arab reaction [i.e., Jordan] is directed principally against the revolution of the Arab masses’ and ‘Israel’s latest move against the Syrian regime [i.e., 7 April] is no more than a manifestation of the overall imperial and reactionary plans’. The statement was intended to identify the US, Israel, and Nasser’s Arab rivals as one in the same in order to galvanise support from the Arab world for his personal crusade.

A twist of fate

Then, in a twist of fate, two American workers from the Agency for International Development (AID) were arrested in Yemen on 25 April for allegedly shooting bazooka rounds into an ammunition dump.[21] The incident was symbolic given that AID was the agency through which American foreign aid was administered. Although President Johnson’s National Security Advisor, Walt Rostow, believed the incident a coincidence, he nevertheless informed the president that Egyptian officials in Yemen took advantage of the situation in order to raid CIA documents from an embassy safe.[22]

What came next was a precursor to Nasser’s call for a war against American imperialism in the Middle East. On 2 May, he gave what British observers described as an ‘important historic speech’ in which he continued his earlier boasts about rejecting American economic pressure but added a call for collective Arab resistance against American imperialism. He proclaimed that he was ‘not prepared to sell even a grain of sand of this country’s soil against 100 million dollars’.[23] President Sallal of Yemen joined Nasser in noting that the detained AID workers were hired ‘to implement CIA plans’ of imposing American dominance in the region.[24] Crucially, Nasser’s speech played on Egypt’s historical disagreements with the UK, which he was now associating with the US.

At the end of the speech, Nasser reiterated his call for a war against Israel, noting that it was the first step towards eradicating foreign influence in the Middle East:

It is an unremitting struggle, and we stand with the revolutionary forces against imperialism in every Arab country, against imperialism everywhere, for imperialism will not stop working against us. They won’t stop plotting, for we are the real resistance to them; we represent our nation’s power to endure, our nation’s will to live, our nation’s aspirations to freedom and to be rid of imperialism and its allies, the first of which is Zionist racialism in Israel.[25]

What Nasser was doing, in actuality, was coalescing Egypt and the Arab world around himself at a time when the ailing Egyptian economy was threatening to undo the legacy of his revolution. It was not unlike what he did in 1956, when he had nationalised the Suez Canal to the acclaim of the Arab world, but at the expense of France and the UK. These developments from February to May 1967 show that his belligerency was becoming increasingly reliant on a narrative of a joint American-Israeli threat to the Arab world.

Towards war

On 14 May, Egyptian troops marched through the streets of Cairo and into the Sinai Peninsula. Unlike an earlier mobilisation of forces against Israel in 1960 that was quietly deployed and later withdrawn without incident, the Egyptian press covered the evolving conflict in detail, with al-Ahram noting that Egypt was ‘ready to enter the battle against Israel’.[26] On 17 May, Radio Cairo noted that following a request for UN Peacekeeping forces to evacuate their position along the Egyptian border with Israel, Nasser had ‘actually sent letters’ to the heads of revolutionary Arab states in order to inform them of Egypt’s ‘determination to implement the joint defence agreement with Syria in case of aggression against the Syrian homeland’.[27] On 18 May, Radio Cairo broadcast lengthy legal justifications of the expulsion of UN Forces, noting that ‘Egypt has the right to ask at any time [for] the withdrawal of this [UN peacekeeping] force’.[28]

The official justification for Egypt’s war-footing was alleged Israeli threats to attack Syria. But within the extensive news commentary and various political speeches in favour of military action there was a consistent anti-American sentiment. In most instances it took the form of describing Israel as an American satellite. According to one broadcast: ‘The people will have no mercy on imperialist installations [i.e. Israel]. The United States will not be able to escape punishment.’[29]

At first, Nasser remained silent about the turn of events and allowed the Egyptian press to spread propaganda. The tactic notably worked on 21 May, when Saudi Arabia, which had been locked in an ongoing five year proxy war against Egypt for mastery over Yemen, did a sudden about-face and publicly praised Nasser:

Perhaps now you realise full well and appreciate that if the United Arab Republic says something, it carries it out; if it promises something, it fulfils that promise; and if it is put to the test by serious events or if it is forced by liars to reveal its might, we find it the most intrepid and the strongest among the states and among mankind. It is brave and trustworthy in facing Zionism and imperialism and a shield to all Arabism and Islam, under the leadership of the pioneer of Arab nationalism, brother President Jamal Abd-an Nasir (sic)…[30]

Finally, on 22 May, Nasser made his first public appearance since the initial mobilisation. When announcing a blockade on Israeli shipping through the Straits of Tiran, he proudly concluded the announcement with an affirmation of Egyptian strength stating: ‘We are not scared by imperialist, Zionist, or reactionary campaigns. We are independent, and we know the taste of freedom. We have built a strong national army and achieved our objectives. We are building our country’.[31] The rhetoric was noticeably a rejection of American aid once-and-for-all and an affirmation of Egyptian strength. At the same time, Radio Cairo had a noticeable spike in anti-American commentary. According to one programme: ‘The United States should also know that there is something else stronger than US might and muscles … it is the willpower of the Arabs and their decisive and firm refusal to concede any of their territory or rights.’[32] Another popular programme openly declared war against America:

We challenge you Israel. No, in fact we do not address the challenge to you, Israel, because you are unworthy of the challenge. But we challenge you America … We challenge you to come near, with Israel, to our gulf – The Gulf of Aqaba. Our soldiers are there with the most powerful war material known in the Middle East. Behind them stand millions of Arabs, including fidai workers carrying in their hands explosives to blow up every American presence throughout the American homeland.[33]

Likewise, another radio show envisioned a showdown with American forces: ‘… the United States is seeking excuses for an armed intervention against the Arab nation to support Israel. The United States, the number one enemy of popular liberty, is showing very great eagerness and is moving toward active intervention.’[34] One newspaper even blamed America for instigating the conflict: ‘… the United States [cannot] erase the fact that it has collaborated with Israel in an attempt to create tension or war between Israel and Syria…’[35]

The Egyptian press attacks on America continued unabated, leading al-Ahram to observe that ‘the confrontation is gradually becoming a confrontation between the Arab nation and the US government more than between the Arab nation and Israel’.[36] At the same time, Nasser continued to garner mass Arab support behind his vendetta against America. On 26 May he said, ‘Israel today is the United States’, effectively declaring that a direct attack on Israel was equivalent to attacking America.[37] Each passing day brought Nasser more support in the Middle East. By 4 June, he had successfully united his friends and foes and was poised to deal a serious death blow to American prestige in the Middle East by attacking Israel. Invoking the millennial Islamic image of God sanctioning the expulsion of unwanted foreigners from Muslim lands, Nasser effectively declared jihad. ‘With the help of God we are proceeding on our path for the sake of our rights of the Palestine people’, he said. ‘God willing, we shall triumph and the Arab nation shall triumph. When God grants you success, no one can defeat you. Thank you brethren, and I pray [to] God for success.’[38] The next day, Nasser’s ambitions were suddenly cut short when Israel launched its surprise pre-emptive attack.

The mobilisation of Egyptian forces in 1967 merits further historical examination in light of the evidence to suggest that it was connected to Nasser’s vendetta against America. Indeed, when Lyndon Johnson sent a private emissary to Cairo in June, his meeting with the Egyptian foreign minister was entirely dominated by a discussion about the breakdown in communication between the two countries and how desperately Egypt had needed the aid, thus raising a question of whether Nasser’s actions in May 1967 had been designed to compel America into supporting him.[39] Current American and Israeli officials may want to take note of this episode to see how history plays out when the US tries and fails to turn a formidable foe into a friend.

References

[1] President Nasser’s Speech at Cairo University on 22 February 1967, FCO 39/245, The British National Archives, Kew, London [henceforth cited as TNA].

[2] Al-Ahram, 23 February 1967, as cited in Ed. Fuad A. Jabber, International Documents on Palestine, 1967 (Beirut: The Institute for Palestine Studies, 1970), p. 496 [henceforth cited as Jabber].

[3] President Nasser’s Speech at Cairo University on 22 February 1967 FCO 39/245, TNA.

[4] Letter from Fletcher to Unwin, No. 1036/67, 2 March 1967, FCO 39/245, TNA.

[5] Minute by D.J. Speares, 24 February 1967, FCO 39/245, TNA.

[6] Al-Ahram, 23 February 1967, as cited in Jabber, p. 495.

[7] Ibid., p. 500 (emphasis added).

[8] Ibid., p. 495 (emphasis added).

[9] Ed. Daniel Dishon, Middle East Record, 1967 (Jerusalem: Israel Universities Press, 1971), p. 547 [henceforth cited as Dishon].

[10] Ibid., p. 550.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Jumhūriyya, 1 January 1967, as cited in Dishon, p. 538.

[13] Jumhūriyya, 22 April 1967, as cited in ibid.

[14] Jumhūriyya, 28 April 1967, as cited in ibid.

[15] See, for example, Hazem Kandil, Soldiers, Spies, and Statesman: Egypt’s Road to Revolt (London: Verso, 2014), p. 77.

[16] Dishon, p. 551.

[17] Mohamed Heikal, ‘We and the US,’ al-Ahram, 24 February; 3, 10, 17 March; 5, 12 May 1967, as cited in Dishon, pp. 49-50.

[18] Al-Ahram, 17 March 1967, as cited in ibid., p. 51.

[19] Resolutions Adopted by the Arab League Council at Its Forty-Seventh Ordinary Meeting, Cairo, 18 March 1967, as cited in Jabber, p. 511.

[20] Cairo Domestic Service, 11 April 1967, as cited in FBIS, 11 April 1967, B1.

[21] See Dishon, p. 54.

[22] Memorandum From the President’s Special Assistant (Rostow) to President Johnson, 10 May 1967, Foreign Relations of the United States [FRUS], 1964-1968, Vol. XVIII.

[23] Cairo Press Review, 3 May 1967, FCO 39/245, TNA.

[24] Sana Domestic Service, 8 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 9 May 1967, E1.

[25] ‘Speech of U.A.R. President Nasir on Labour Day, 2 May 1967,’Al-Ahram, 3 May 1967, as cited in Jabber, p. 525 (emphasis added).

[26] See, for example, Radio Cairo, 17 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 17 May 1967, B1.

[27] Radio Cairo, 17 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 17 May 1967, B2.

[28] Radio Cairo, 18 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 18 May 1967, B1-B2.

[29] Radio Cairo, 17 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 18 May 1967, B4.

[30] Radio Cairo, 21 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 22 May 1967, B1.

[31] Radio Cairo, 23 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 23 May 1967, B4.

[32] Radio Cairo, 23 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 24 May 1967, B4.

[33] Radio Cairo, 23 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 24 May 1967, B5.

[34] Radio Cairo, 24 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 24 May 1967, B6.

[35] Radio Cairo, 24 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 24 May 1967, B7.

[36] Radio Cairo, 26 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 26 May 1967, B1.

[37] Radio Cairo, 26 May 1967, as cited in FBIS, 29 May 1967, B2.

[38] Radio Cairo, 4 June 1967, as cited in FBIS, 5 June 1967, B3.

[39] Farewell Call on Foreign Minister Riad, Memorandum of Conversation, 3 June 1967, USNA Middle East Crisis Files, 1967, Box 2. Riad also offered to show tape recorded evidence of how the CIA wanted to assassinate Nasser.