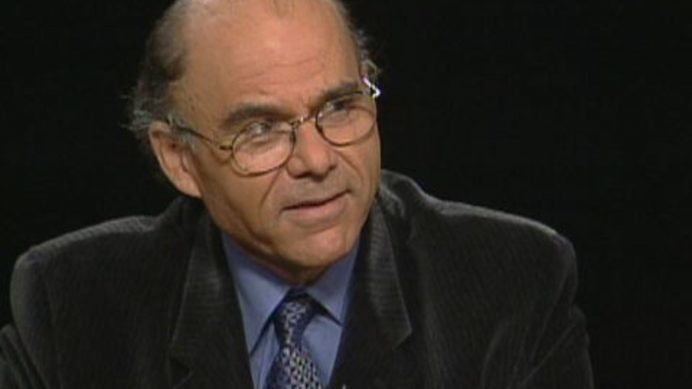

Kanan Makiya is known for two seminal books – Republic of Fear, which called attention to the cruel human rights abuses in Saddam’s Iraq, and Cruelty and Silence which highlighted how many Arab intellectuals and Western Leftists were turning a blind eye to that cruelty, their silence justified on ‘ideological’ grounds. A supporter of the Iraq War as a member of the Iraqi opposition, he later became a critic of the conduct of the intervention. Most recently, he has published a novel, The Rope, about Iraqi failure in the wake of the 2003 American invasion, as seen through the eyes of a Shiite militiaman whose participation in the execution of Saddam Hussein changes his life in ways he could never have anticipated.

In this anniversary year of the Six-Day War, Fathom spoke to him about the legacy of the Six Day War for the Arab World, for Arab politics, for the left, and for Kanan Makiya.

Alan Johnson: Growing up in Iraq, what was the feeling amongst your circle about Nasserism?

Kanan Makiya: Since the 1958 coup in Iraq, led by Brigadier Abd al Karim Qasim, which overthrew the monarchy and replaced it with the republic, the Nasserist movement in Iraq, never very strong in the first place, was essentially divided. The country was divided between Iraqists who put Iraq first and Arab nationalists who wanted the unification of the Arab world. In the years 1958 67, when I was growing up, this was a very divisive and defining political issue.

AJ: Can you recall the mood in Iraqi society immediately prior to the 1967 war? Was it hopeful?

KM: Absolutely not. Iraq differed from other Arab countries in that respect. Iraqi society was exhausted by 10 years of coups and counter coups. These were bloody affairs; in 1963 Qasim was overthrown by the Ba’ath party and killed in a spectacularly cruel and terrible way. The country was riven by a fundamental conflict between the Iraqi Communist Party, the largest and most popular party in the country, and the rising influence of the Arab nationalists. By the time of the 1967 war you could say people were exhausted and despondent.

AJ: You were born in 1949, so you were 18 in 1967. What are your dominant memories of the six days? You described it to me some years ago as the ‘first political event of my life’.

KM: Yes, the first few days of the war were the first in-depth emotionally felt political event of my life. Undoubtedly this was the event that steered me away from a career in mathematics to a lifelong involvement with politics. Before that I was an ordinary totally focused high school student. I was not thinking at all about the world outside my school and studies. The war changed that for me and a whole generation. I came of age politically because of the 1967 war. The incident you are referring to I remember very clearly. On the second or third day of the war, we were gathered outside our college having an argument over what was actually happening. I had the benefit of having listened to the BBC, so I had heard of the utter devastation of the Egyptian air force in the first few hours of the war, and it seemed a perfectly factual description of events. The other students relied more on Baghdad radio, which was trumpeting the great successes of the Arab armies even as they were being defeated on the ground. The war was over in the first few hours. The contrast between that fact as reported buy the BBC and the lies of the Iraqi radio, was my first experience of the great fault line that existed between rhetoric and reality, in Arab nationalist political life.

There is one other event I should mention. As a young boy I witnessed the gruesome spectacle of the Ba’ath party televising the bullet ridden body of Qasim, propped up on a chair while a soldier sauntered around him, and the camera cutting to scenes of devastation at the Ministry of Defence where he had made his last stand. It had been a bloody coup in 1963. The soldier grabbed his lolling head by the hair and spat into it. As children we were glued to our newly arrived television sets, and this clip was shown repeatedly. That scene forever marked me; it appears in a very graphic way in The Republic of Fear, and, reading it, you can sense that it is personal.

AJ: What have been the most important legacies of the 1967 war for the Arab world and the Arab left?

KM: The defeat itself was not the most important thing. It was of course enormous, but countries can get over big defeats. The practical consequences of the 1967 war are of course still with us in the shape of the occupied territories and the Palestinian Israeli conflict. But the main legacy for today is how the defeat was handled and absorbed into Arab culture. After 1967, Arab culture began to internalise the state of being defeated. It was never able to come to terms with what happened. That has had devastating consequences.

AJ: What do you mean when you say Arabs have never come to terms with the defeat? How did it practically impede the development of Arab society and politics?

KM: The idea that was popularised after the 1967 war was ‘rejection’. It began with the Khartoum Summit and the three noes. The Arabs’ rejection was a refusal to accept the 1967 defeat, and an insistence that the defeat was a tiny blip preceding the inevitable demise of Israel that would result from encirclement by a far larger Arab population. This notion penetrated deeply into ways of thinking about politics, and into the politics of the Palestinian resistance movement in its early years. This is why there was such a fierce rejection of the Camp David Accords in the Arab world. Today, you see it in the rejection of normalisation with Israel. This has become a very deeply ingrained bunker-like mentality to what is or is not important in politics. Things are finally changing now because of the scale of the catastrophes engulfing Arab states, catastrophes that clearly have nothing to do with the Palestinians or Israel. Since 2011 especially, we can see a new relationship evolving between the Arab world and Israel. However, the old legacy still haunts Arab politics, and in particular the politics of the intelligentsia.

AJ: You have said that a whole generation of Arabs of your age threw themselves into supporting the Palestinians post 67 at the expense of facing the degradation of politics in their own countries. Why do you think that was? What impact has that turn had on Arab society?

KM: A generation of so called radical regimes – Nasserism, Ba’athism – had been defeated in 1967. The slogans of Pan Arabism, one of the most prominent political ideologies in the Fertile Crescent from the late 1950s through the 1960s, were proven to be bankrupt, but not always accepted as such. As events pulled the wool away from our eyes after 1967, we looked for alternatives. New organisations came forward. Palestinian organisations, who had in the past relied on the Arab regimes to conduct their struggle; these were now acting on their own, saying they could liberate themselves. The organisations that emerged used the rhetoric of those years – socialism, the progressive rhetoric of the left, Arab revolution, Maoism. They were very much organisations of the 1960s, although their period of ascendancy lasted only for a brief time. But early on young men like myself were attracted to them. On the surface they looked like genuine socialist alternatives to those defunct Nasserite regimes in Syria, Egypt and Iraq.

These credentials were very shortly to be tested in Jordan during Black September and later in Lebanon, where they essentially ended up fighting a thirteen year long civil war; a war we described as being about progressives and reactionary forces but which turned out to be a mainly sectarian war with no good or bad sides. That became obvious, and soon these shining paragons of politics were exposed to have turned into local occupation armies in different parts of Jordan and Lebanon, running protection rackets as all the other militias did.

The Lebanese civil war, followed by the Iranian Islamic revolution and then the Iraq-Iran war were the three main turning points in my life, leading me to seek out a completely different way of thinking about politics; to turn away from blueprints that talked about the Arab world as a single unit facing external aggressors – Imperialism, Zionism – and to look inwards to the defects within my own society in Iraq. I felt that my fundamental error in the past had been to avoid looking inwards in favour of looking outwards; this was the error of a whole generation. This realisation led me to turn away from questions about the 1967 war and the Arab Israeli conflict, and begin to examine the dictatorial and totalitarian nature of the Iraqi Ba’athist state in my first book, The Republic of Fear which was published in 1989.

The failure of the western left too lay its inability to look critically at organisations like the Palestinian resistance movement, and to essentially adopt them as the vanguard of progressive socialism. And the failure of the left was its unwillingness to change this stance even after events on the ground proved otherwise. It’s one thing to have wishful thinking when an organisation has not been tested. It is another when they were shown to behave as they did in the Lebanon civil war. Plus, they were consistently adopting a maximalist policy that did not lend itself to partial solutions. They chose to adopt the politics of armed struggle, of banging away at Israel from the outside, rather than work for improvements to human rights and civil liberties for Israeli Arabs and West Bank Palestinians. The major debates over these kinds of questions were resolved in favour of the disastrous policy of armed struggle; the dominant view became that the way you brought about reform or fundamental change was by waging armed struggle from your base in marginal communities like the refugee camps surrounding Israel, rather than adopting a politics of organising amongst Israeli and West Bank Palestinians. Along with this came the fetishisation of the Kalashnikov and armed struggle that penetrated Palestinian political culture, the result being no real gains were made for Palestinians in any sphere.

AJ: It is the Islamists who preoccupy our attention in the West and in the region today. Was the political wasteland you describe after 1967 – the failure of pan Arabism and the Arab left – the context in which the Islamists found a base and grew.

KM: The inability to accept defeat and to move on was passed from the Arab nationalists to the Islamists. We see in both movements an inability to deal with or even want to understand the nature of Israel, as well as an unwillingness to truly work towards improving the rights of Palestinians through a realistic, step by step framework. The Islamists inherited this way of thinking from a previous generation, my generation, even though their main preoccupations lay elsewhere.

To illustrate my point: I had a colleague who was an Islamist militant activist who spent his life fighting Hussein in Iraq. In conversation in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, he told me it was not possible for Arabs to commit such an ingenious operation. He had internally absorbed the 1967 defeat to such an extent that he could not imagine Arabs were capable of an event of such magnitude. This of this as 1967 speaking through him; he was part of a generation that internalised the defeat and turned it into something else.

AJ: I often think the odyssey of the Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad speaks to the legacy of 1967. A real nation builder who improved transparency, governance and infrastructure, a man who had the world taking seriously the prospect of a Palestinian state. His reward was to be pushed aside by Abbas and the Fatah chieftains.

KM: I agree. Look at how hard it was for Salam Fayyad to emerge, and then compare it to his subsequent marginalisation by other Palestinian leaders.

AJ: The Arab spring could have been a real transformational moment in the Arab world. How did you respond to it?

KM: I was enthusiastic. I felt enormously vindicated. I thought that everything I had argued for was coming to a head. There were large sections of the population rejecting the very politics that I had spent decades trying to reject, a stance for which I had been pilloried by other Arabs. And by the way I think it is important to separate the spontaneity of those early demonstrations from the manner in which they later evolved, or were taken over by dark and repressive forces. There was something very precious there in the beginning, and I refuse to say that there was an inevitable connection between those days and what happened later.

Democratic politics is about operating at the margins of what is possible. If there was a 95 per cent chance of democracy happening in Iraq in 2003 there wouldn’t have been a war in the first place. This was a deeply abused society that had a marginal chance of moving in a better direction. If you do not act on this margin of possibility that a better, more equal and less repressive political order could come into being, then will change ever happen? Of course not Given the kind of repressive regimes we have in the Arab world, there is a risk that events will turn in a violent direction, and Islamist organisations who have filled the vacuum that more secular organisations have left behind, will jump on the bandwagon. That is where we are now.

AJ: Listening to you, I am reminded of the title of Irving Howe’s beautiful memoir Margin of Hope. To end, could you tell us why you decided to write a novel and why this subject?

KM: The novel is an exploration of the question of Iraqi responsibility for the failures of the American war of 2003. Although every mistake that could possibly have been made by the US occupation was made, and more, I believe the principle responsibility for the colossal failures of Iraq post 2003 – the civil war, the emergence of ISIS in 2014 – lies primarily with the Iraqi leaders and political elites that were empowered by the 2003 war.

In the novel, I use a deeply symbolic event that happened on the day of the fall of Saddam’s statue, 10 April 2003. The son of a prominent Grand Ayatollah who had joined the uprising in 1991 and fled to London, returns two weeks before the 2003 war and is murdered by the son of another Grand Ayatollah. This was an intra Shi’ite event. And in that murder and the cover up by the Shi’ite elite put in power by the CPA lay the seeds of the kind of sectarian politics that led us to the civil wars and the destruction that followed.

There is something very historic about the 2003 war that is rarely discussed in the West. Iraqi Shi’ites were empowered for the first time in their long history, and the Americans did this fully aware of what they were doing. It is an enormous event when an oppressed community suddenly finds itself exercising state power. Think of the 2003 war as a kind of test. The novel is fundamentally about the way Shi’ites dealt with their new role. Very badly obviously, and the murder highlights that.

What Kanan Makiya has to say is interesting but he does not mention that Iraq’s humiliation at the Arab defeat in the 1967 war translated itself into vicious state-sanctioned reprisals against the three thousand Jews still living in Iraq. Half a million people came to celebrate under the corpses of Jews executed as ‘Zionist spies’. This was just the start of a reign of terror resulting in the arrest and disappearance of dozens of Jews.

The Arabs have learned nothing from history. All they can do is blame others for their downfall I/O looking in the mirror.

I read The Rope and Michael Lewis’ The Undoing Project in the same week. What was striking to me was the comparison of how young students address their leaders and leaders in the Arab world and Israel. In The Rope, a young charismatic student is torn to shreds by his teacher when he dares to ask an “egocentric” question, while in The Undoing Project, Israeli students yell out questions at visiting professors who cannot develop their ideas fully. Israelis in the military adopted the “10th Man Rule” when they confronted their own failures of imagination following the 1973 Yom Kippur War: when 9 generals agree on a policy, the tenth one has to disagree and try to pull apart their assumptions and findings. This strategy made its way into US military thinking after 9/11 and is called “Red Teaming”.

Seems to me that what is holding the Arab world back is the freedom to question their own leaders.